Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry (IUPAC Recommendations 2005)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IR-3 Elements and Groups of Elements (March 04)

1 IR-3 Elements and Groups of Elements (March 04) CONTENTS IR-3.1 Names and symbols of atoms IR-3.1.1 Systematic nomenclature and symbols for new elements IR-3.2 Indication of mass, charge and atomic number using indexes (subscripts and superscripts) IR-3.3 Isotopes IR-3.3.1 Isotopes of an element IR-3.3.2 Isotopes of hydrogen IR-3.4 Elements (or elementary substances) IR-3.4.1 Name of an element of infinite or indefinite molecular formula or structure IR-3.4.2 Name of allotropes of definite molecular formula IR-3.5 Allotropic modifications IR-3.5.1 Allotropes IR-3.5.2 Allotropic modifications constituted of discrete molecules IR-3.5.3 Crystalline allotropic modifications of an element IR-3.5.4 Solid amorphous modifications and commonly recognized allotropes of indefinite structure IR-3.6 Groups of elements IR-3.6.1 Groups of elements in the Periodic Table and their subdivisions IR-3.6.2 Collective names of groups of like elements IR-3.7 References IR-3.1 NAMES AND SYMBOLS OF ATOMS The origins of the names of some chemical elements, for example antimony, are lost in antiquity. Other elements recognised (or discovered) during the past three centuries were named according to various associations of origin, physical or chemical properties, etc., and more recently to commemorate the names of eminent scientists. In the past, some elements were given two names because two groups claimed to have discovered them. To avoid such confusion it was decided in 1947 that after the existence of a new element had been proved beyond reasonable doubt, discoverers had the right to IUPACsuggest a nameProvisional to IUPAC, but that only Recommendations the Commission on Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry (CNIC) could make a recommendation to the IUPAC Council to make the final Page 1 of 9 DRAFT 2 April 2004 2 decision. -

Rate Constants for Reactions Between Iodine- and Chlorine-Containing Species: a Detailed Mechanism of the Chlorine Dioxide/Chlorite-Iodide Reaction†

3708 J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 3708-3719 Rate Constants for Reactions between Iodine- and Chlorine-Containing Species: A Detailed Mechanism of the Chlorine Dioxide/Chlorite-Iodide Reaction† Istva´n Lengyel,‡ Jing Li, Kenneth Kustin,* and Irving R. Epstein Contribution from the Department of Chemistry and Center for Complex Systems, Brandeis UniVersity, Waltham, Massachusetts 02254-9110 ReceiVed NoVember 27, 1995X Abstract: The chlorite-iodide reaction is unusual because it is substrate-inhibited and autocatalytic. Because - analytically pure ClO2 ion is not easily prepared, it was generated in situ from the rapid reaction between ClO2 and I-. The resulting overall reaction is multiphasic, consisting of four separable parts. Sequentially, beginning with mixing, these parts are the (a) chlorine dioxide-iodide, (b) chlorine(III)-iodide, (c) chlorine(III)-iodine, and (d) hypoiodous and iodous acid disproportionation reactions. The overall reaction has been studied experimentally and by computer simulation by breaking it down into a set of kinetically active subsystems and three rapidly established - equilibria: protonations of chlorite and HOI and formation of I3 . The subsystems whose kinetics and stoichiometries were experimentally measured, remeasured, or which were previously experimentally measured include oxidation of - iodine(-1,0,+1,+3) by chlorine(0,+1,+3), oxidation of I by HIO2, and disproportionation of HOI and HIO2. The final mechanism and rate constants of the overall reaction and of its subsystems were determined by sensitivity analysis and parameter fitting of differential equation systems. Rate constants determined for simpler reactions were fixed in the more complex systems. A 13-step model with the three above-mentioned rapid equilibria fits the - -3 - -3 - - overall reaction and all of its subsystems over the range [I ]0 < 10 M, [ClO2 ]0 < 10 M, [I ]0/[ClO2 ]0 ) 3-5, pH ) 1-3.5, and 25 °C. -

Kinetics and Mechanism of Polythionate Oxidation to Sulfate at Low Ph by O2 and Fe3+

Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, Vol. 67, No. 23, pp. 4457–4469, 2003 Copyright © 2003 Elsevier Ltd Pergamon Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 0016-7037/03 $30.00 ϩ .00 doi:10.1016/S0016-7037(03)00388-0 3؉ Kinetics and mechanism of polythionate oxidation to sulfate at low pH by O2 and Fe 1, 2 1,2 GREGORY K. DRUSCHEL, *ROBERT J. HAMERS, and JILLIAN F. BANFIELD † 1Departments of Geology and Geophysics and 2Chemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706 USA (Received October 16, 2002; accepted in revised form May 30, 2003) 2Ϫ Abstract—Polythionates (SxO6 ) are important in redox transformations involving many sulfur compounds. Here we investigate the oxidation kinetics and mechanisms of trithionate and tetrathionate oxidation between pH 0.4 and pH 2 in the presence of Fe3ϩ and/or oxygen. In these solutions, Fe3ϩ plus oxygen oxidizes tetrathionate and trithionate at least an order of magnitude faster than oxygen alone. Kinetic measurements, coupled with density functional calculations, suggest that the rate-limiting step for tetrathionate oxidation involves Fe3ϩ attachment, followed by electron density shifts that result in formation of a sulfite radical and 0 S3O3 derivatives. The overall reaction orders for trithionate and tetrathionate are fractional due to rearrange- ment reactions and side reactions between reactants and intermediate products. The pseudo-first order rate coefficients for tetrathionate range from 10Ϫ11 sϪ1 at 25°C to 10Ϫ8 sϪ1 at 70°C, compared to 2 ϫ 10Ϫ7 sϪ1 Ϯ at 35 °C for trithionate. The apparent activation energy (EA) for tetrathionate oxidation at pH 1.5 is 104.5 4.13 kJ/mol. -

DBDMH As a Processing Aid to the List of Allowed Substances in the National Organic Program

CBI Deleted ALBEMARLE CORPORATION Petition to add DBDMH as a processing aid to the List of Allowed Substances in the National Organic Program This petition contains Confidential Business Information. This includes “trade secrets” related to the production process and quality control tests and data. This information is commercially valuable, used in Albemarle business and maintained in secrecy. Introduction Hypobromous acid (HOBr) derived from 1,3-dibromo-5,5-dimethylhydantoin (DBDMH, CAS No. 77-48-5) exhibits antimicrobial effects in water. It is used as a post-harvest intervention in the beef industry, and results from laboratory studies and commercial trials have shown a reduction in E. coli and Salmonella levels1 with HOBr from DBDMH. It can be used to control bacterial numbers on beef hides, carcasses, heads and organs. This chemistry is also used in the poultry processing industry. DBDMH is a stable white to off-white granular solid. In water, DBDMH undergoes a hydrolysis reaction to form two molecules of hypobromous acid (HOBr) and one molecule of dimethylhydantoin (DMH). During use, DBDMH is placed into a flow-through chemical feeder. The aqueous output of this feeder is mixed with a separate stream of water to dilute the HOBr to the desired level, and supply a constant stream of HOBr to the DBDMH application system. The water flow to the feeder and the water flow for dilution can be controlled to achieve the proper dilution to obtain the desired HOBr concentration. Hypobromous acid is the active antimicrobial agent in the water applied to the beef. The oxidizing action of hypobromous acid kills the bacteria. -

Measurement Report: Indirect Evidence for the Controlling Influence of Acidity on the Speciation of Iodine in Atlantic Aerosols

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 13067–13076, 2021 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-13067-2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Measurement report: Indirect evidence for the controlling influence of acidity on the speciation of iodine in Atlantic aerosols Alex R. Baker1 and Chan Yodle1,a 1Centre for Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, NR4 7TJ, UK anow at: Department of Environmental Science, Faculty of Science and Technology, Chiang Mai Rajabhat University, Chiang Mai, 50300, Thailand Correspondence: Alex R. Baker ([email protected]) Received: 26 January 2021 – Discussion started: 26 April 2021 Revised: 22 July 2021 – Accepted: 10 August 2021 – Published: 2 September 2021 Abstract. The speciation of soluble iodine and major- 1 Introduction ion composition were determined in size-fractionated aerosols collected during the AMT21 cruise between Avon- mouth, UK, and Punta Arenas, Chile, in September– Iodine (I) plays a significant role in the destruction of ozone November 2011. The proportions of iodine species (iodide, (O3) in the atmosphere (Davis et al., 1996; Saiz-Lopez et iodate and soluble organic iodine (SOI)) varied markedly be- al., 2012), being responsible for ∼ 30 % of O3 loss in the tween size fractions and with the extent to which the samples marine boundary layer (MBL) (Prados-Roman et al., 2015). were influenced by pollutants. In general, fine mode aerosols Oceanic emission, principally of volatile I2 and hypoiodous (< 1 µm) contained higher proportions of both iodide and acid (HOI) formed through the reaction of O3 with iodide − SOI, while iodate was the dominant component of coarse (I ) at the sea surface (Carpenter et al., 2013), is the main (< 1 µm) aerosols. -

Chemical Nomenclature

Chemical Nomenclature Many everyday and historically important chemical compounds have common names. For example, water is the common name for H2O, baking soda is the common name for NaHCO3 and KNO3, an important component of gunpowder, is known as saltpeter. However, since there are over 50 million known chemical compounds, learning a common name for each one would be very difficult. Chemical nomenclature is a systematic method of naming chemical compounds. Having a system for naming means that we don’t have to learn 50 million names, we only have to learn the rules for naming. It also allows scientists who speak different languages to communicate effectively. The rules for chemical nomenclature come from the International Union for Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), a group made up of chemists from all over the world. In this exercise you will learn rules for naming ionic and covalent compounds and learn to predict the ratios that chemicals combine in based on their ionic charge. A. Naming Type I Binary Ionic Compounds Type I binary ionic compounds are made of (1) a metal that can only have one possible charge and (2) a nonmetal. The metal is the cation, or positively charged ion and the nonmetal is the anion, or negatively charged ion. In the chemical formula, the cation is always written first and the anion is written second. Cations that fall under Type I naming include Group 1A alkali metals, which always form 1+ cations and Group 2A alkaline earth metals which always form 2+ cations. Most transition metals fall under Type II naming, discussed below, but the exceptions are silver (Ag), which always forms 1+ cations and zinc (Zn) and cadmium (Cd), which always form 2+ cations. -

CHEM 1411 Nomenclature Homework - Answers Part I

1 CHEM 1411 Nomenclature Homework - Answers Part I 1. The following are a list of binary and pseudobinary ionic compounds. Write the name when the formula is given. Write the formula when the name is given. (a) AlCl3 aluminum chloride (k) rubidium oxide Rb2O (b) AuBr3 gold (III) bromide (l) chromium (III) selenide Cr2Se3 (c) Na2S sodium sulfide (m) barium iodide BaI2 (d) Cu3P2 copper (II) phosphide (n) copper (I) fluoride CuF (e) Fe(OH)2 iron (II) hydroxide (o) copper (II) fluoride CuF2 (f) NH4OH ammonium hydroxide (p) strontium cyanide Sr(CN)2 (g) Co(CH3COO)3 cobalt (III) acetate (q) mercury (II) bromide HgBr2 (h) Zn(SCN)2 zinc thiocyanate (r) mercury (I) bromide Hg2Br2 (i) CaCrO4 calcium chromate (s) magnesium permanganate Mg(MnO4)2 (j) K2Cr2O7 potassium dichromate (t) lithium nitride Li3N 2. The following are lists of covalent compounds. Write the name when a formula is given. Write the formula when given a name. (a) CSe2 carbon diselenide (h) dichlorine heptoxide Cl2O7 (b) SF6 sulfur hexafluoride (i) xenon tetrafluoride XeF4 (c) BrF5 bromine pentafluoride (j) carbon monoxide CO (d) P4O10 tetraphosphorous decoxide (k) oxygen O2 (e) Cl2O dichlorine oxide (l) diboron trioxide B2B O3 (f) NH3 ammonia (m) arsenic trifluoride AsF3 (g) N2 dinitrogen or nitrogen (n) diiodine I2 2 3. The following are lists of acids or acid-forming compounds. Write the name when the formula is given. Write the formula when the name is given. (a) H3PO2 hypophosphorous acid (k) hydrogen cyanide HCN (g) (b) H2SO4 sulfuric acid (l) periodic acid HIO4 (c) HClO hypochlorous acid (m) hypochlorous acid HClO (d) H3PO4 phosphoric acid (n) nitric acid HNO3 (e) HBrO4 perbromic acid (o) acetic acid CH3CO2H (f) HIO2 iodous acid (p) chloric acid HClO3 (g) HI (g) hydrogen iodide (q) perbromic acid HBrO4 (h) HI (aq) hydroiodic acid (r) hydrofluoric acid HF (aq) (i) HCN (aq) hydrocyanic acid (s) phosphorous acid H3PO3 (j) HBrO hypobromous acid (t) hydrosulfuric acid H2S (aq) 4. -

Standard Thermodynamic Properties of Chemical

STANDARD THERMODYNAMIC PROPERTIES OF CHEMICAL SUBSTANCES ∆ ° –1 ∆ ° –1 ° –1 –1 –1 –1 Molecular fH /kJ mol fG /kJ mol S /J mol K Cp/J mol K formula Name Crys. Liq. Gas Crys. Liq. Gas Crys. Liq. Gas Crys. Liq. Gas Ac Actinium 0.0 406.0 366.0 56.5 188.1 27.2 20.8 Ag Silver 0.0 284.9 246.0 42.6 173.0 25.4 20.8 AgBr Silver(I) bromide -100.4 -96.9 107.1 52.4 AgBrO3 Silver(I) bromate -10.5 71.3 151.9 AgCl Silver(I) chloride -127.0 -109.8 96.3 50.8 AgClO3 Silver(I) chlorate -30.3 64.5 142.0 AgClO4 Silver(I) perchlorate -31.1 AgF Silver(I) fluoride -204.6 AgF2 Silver(II) fluoride -360.0 AgI Silver(I) iodide -61.8 -66.2 115.5 56.8 AgIO3 Silver(I) iodate -171.1 -93.7 149.4 102.9 AgNO3 Silver(I) nitrate -124.4 -33.4 140.9 93.1 Ag2 Disilver 410.0 358.8 257.1 37.0 Ag2CrO4 Silver(I) chromate -731.7 -641.8 217.6 142.3 Ag2O Silver(I) oxide -31.1 -11.2 121.3 65.9 Ag2O2 Silver(II) oxide -24.3 27.6 117.0 88.0 Ag2O3 Silver(III) oxide 33.9 121.4 100.0 Ag2O4S Silver(I) sulfate -715.9 -618.4 200.4 131.4 Ag2S Silver(I) sulfide (argentite) -32.6 -40.7 144.0 76.5 Al Aluminum 0.0 330.0 289.4 28.3 164.6 24.4 21.4 AlB3H12 Aluminum borohydride -16.3 13.0 145.0 147.0 289.1 379.2 194.6 AlBr Aluminum monobromide -4.0 -42.0 239.5 35.6 AlBr3 Aluminum tribromide -527.2 -425.1 180.2 100.6 AlCl Aluminum monochloride -47.7 -74.1 228.1 35.0 AlCl2 Aluminum dichloride -331.0 AlCl3 Aluminum trichloride -704.2 -583.2 -628.8 109.3 91.1 AlF Aluminum monofluoride -258.2 -283.7 215.0 31.9 AlF3 Aluminum trifluoride -1510.4 -1204.6 -1431.1 -1188.2 66.5 277.1 75.1 62.6 AlF4Na Sodium tetrafluoroaluminate -

Deracemization of Sodium Chlorate with Or Without the Influence of Sodium Dithionate Manon Schindler

Deracemization of sodium chlorate with or without the influence of sodium dithionate Manon Schindler To cite this version: Manon Schindler. Deracemization of sodium chlorate with or without the influence of sodium dithionate. Cristallography. Normandie Université, 2020. English. NNT : 2020NORMR004. tel- 02521046v2 HAL Id: tel-02521046 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02521046v2 Submitted on 15 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THÈSE Pour obtenir le diplôme de doctorat Spécialité Physique Préparée au sein de l’Université de Rouen Normandie Deracémisation du chlorate de sodium avec et sans l’influence du dithionate de sodium Présentée et soutenue par Manon SCHINDLER Thèse soutenue publiquement le 13 mars 2020 devant le jury composé de Mme. Elizabeth HILLARD Dr. Hab. Université de Bordeaux Rapporteur M. Elias VLIEG Pr. Université Radboud de Nimègue Rapporteur Mme. Sylvie MALO Pr. Université de Caen Normandie Présidente M. Woo Sik KIM Pr. Université Kyung Hee de Séoul Examinateur M. Gérard COQUEREL Pr. Université de Rouen Normandie Directeur de thèse Thèse dirigée par Gérard COQUEREL, professeur des universités au laboratoire Sciences et Méthodes Séparatives (EA3233 SMS) THÈSE Pour obtenir le diplôme de doctorat Spécialité Physique Préparée au sein de l’Université de Rouen Normandie Deracemization of sodium chlorate with or without the influence of sodium dithionate Présentée et soutenue par Manon SCHINDLER Thèse soutenue publiquement le 13 mars 2020 devant le jury composé de Mme. -

Sop Pyrophoric 2 12/16/2019

Owner DOC. NO. REV. DATE C.H.O SOP PYROPHORIC 2 12/16/2019 DOC. TITLE SOP FOR PYROPHORIC CHEMICALS Environmental Health & Safety STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES (SOP) FOR WORKING WITH PYROPHORIC CHEMICALS AT AMHERST COLLEGE ___________________________________________________________________ General Information Pyrophoric Chemicals are solid, liquid, or gas compounds that, when exposed to air or moisture at or below 54°C (130°F), can spontaneously ignite. Examples of Pyrophoric chemicals used at Amherst College Laboratories include: sodium hydride, zinc powder, and Grignard reagents. See the “Appendix” page below for a full list of Pyrophoric Chemicals. Pyrophoric chemicals are often used as catalysts in chemical reactions or as reducing and deprotonating agents in organic chemistry. Note that Pyrophoric chemicals may also be characterized by other hazards, hence, users of these chemicals may also need to refer to other SOPs that cover other hazards. In addition, each individual chemical’s Safety Data Sheet (SDS) should be consulted before they are used. _____________________________________________________________________________________ Personal Protective Equipment When working with Pyrophoric Chemicals, the following personal protective equipment (PPE) must be worn, at a minimum. Depending on the specific chemical, other forms of protection might be required. Consult the SDS for each chemical before use: Splash goggles Lab coat (Fire resistant lab coat highly recommended) Long pants Close toed shoes Gloves – Nitrile gloves adequate for accidental contact with small quantities. However, the use of fire resistant Nomex/ Leather Pilot’s gloves is highly recommended _____________________________________________________________________________________ Safety Devices All work with Pyrophoric chemicals must be done in a glove box, vacuum manifold, or any enclosed inert environment. If work must be done in a fume hood, ensure that the hood sash is in the lowest feasible position. -

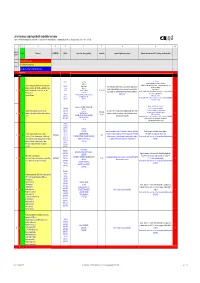

List of Substances Subject to Prohibited / Undesirable / Declaration

List of substances subject to prohibited / undesirable / declaration Appendix 1 to the Guidelines to Design and Purchasing Prohibition of Harmful Substances : ebmpapstMulfingen: 90-001 ebmpapstSt.Georgen: WN 3-12.2 ebmpapstLandshut: 60118.00040 (Ver. 5.0-31.07.2008) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Consecu N - new Substance EU-INDEX-No.: CAS-No. Source (law, decree, guideline). Hazard/risk example of application/occurrence Remarks and comments (of 0.1% deviating consideration limit) tive No. V = prohibited (verboten) U = undesirable (unerwünscht) D = subject to declaration (deklarationspflichtig) V = prohibited RoHS from 100 ppm 7439-92-1 TRGS 905, Pb-stabilisers and pigments are subject to declaration. GefStoffV, Prohibited: Anhydrite neutral lead carbonate, lead hydrogen carbonate and lead Lead and compounds (red lead oxide, lead sulphate, lead (7446-14-2 ChemVerbotsV, cable coating, heat transfer medium for accumulators, hybrid integrated sulphate as dye pigment hydrogen carbonate, lead carbonate, lead phtalates, lead 1319-46-6 BatterieV, circuits, stabilisers in plastics, vessels and pipes for aggressive liquids, < 0.4 % in batteries 1 V N acetates, lead phosphates, lead stereates , etc) lead 598-63-0 2002/95/EG (RoHS), K3, R 1, R 3 V E F according to RoHS: Lead as alloying additive in aluminum (up to 0.4 mass%) in steel (up to 67/458/EEC pigment production, lead alloys, anti-corrosion agents (fuel additives), chromate: refer to 0.35 mass%), in copper (up to 4%), 301-04-2 76/769/EEC (89/667/EEC, 97/10/EC, 97/56/EC) soldering agent chromium (VI) -

Chapter 5 PROPERTIES of IRRADIATED LBE and Pb*

Chapter 5 PROPERTIES OF IRRADIATED LBE AND Pb* 5.1 Introduction Lead and LBE possess favourable properties as both a spallation neutron target material and as a coolant for ADS and reactor systems. For ADS applications, these properties include: 1) a high yield of about 28 n for LBE and 24 n for Pb per 1 GeV proton; 2) both melts have an extremely small neutron absorption cross-section; (3) a small scattering cross-section [Gudowski, 2000]. As a coolant, lead and LBE possess: 1) high boiling points; 2) high heat capacities; (3) inert behaviour with respect to reaction with water. For safe operation and post-irradiation handling of LBE and Pb it is necessary to know the nuclides generated during irradiation. Some of these nuclides are volatile, hazardous and rather long-lived. Their behaviour within the system is strongly influenced by the environment including the oxygen content and temperature. If volatiles are produced, their release rates under specific conditions must be evaluated. The release of volatiles may be prevented by the application of a suitable absorber. Protons of 600 MeV energy induce spallation reactions in heavy materials such as Pb and Bi. These reactions generate direct spallation products, consisting of nuclei with masses close to that of the target nuclei. At the high energies involved multiple inelastic reactions are possible. Therefore, one must expect a large number of isotopes as products. For instance, reactions on Pb generate Hg isotopes roughly from 180Hg to 206Hg. Similarly, reactions of protons on Bi generate Po isotopes up to 209Po. 210Po is generated by neutron capture on 209Bi, and subsequent E decay of the compound nucleus 210Bi.