Heloise's Letters, Abelard Throws Himself Into A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor RESEARCH IN MEDIEVAL CULTURE Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Medieval Institute Publications is a program of The Medieval Institute, College of Arts and Sciences Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor MEDIEVAL INSTITUTE PUBLICATIONS Western Michigan University Kalamazoo Copyright © 2015 by the Board of Trustees of Western Michigan University All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Taylor, Robert A. (Robert Allen), 1937- Bibliographical guide to the study of the troubadours and old Occitan literature / Robert A. Taylor. pages cm Includes index. Summary: "This volume provides offers an annotated listing of over two thousand recent books and articles that treat all categories of Occitan literature from the earli- est enigmatic texts to the works of Jordi de Sant Jordi, an Occitano-Catalan poet who died young in 1424. The works chosen for inclusion are intended to provide a rational introduction to the many thousands of studies that have appeared over the last thirty-five years. The listings provide descriptive comments about each contri- bution, with occasional remarks on striking or controversial content and numerous cross-references to identify complementary studies or differing opinions" -- Pro- vided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-58044-207-7 (Paperback : alk. paper) 1. Provençal literature--Bibliography. 2. Occitan literature--Bibliography. 3. Troubadours--Bibliography. 4. Civilization, Medieval, in literature--Bibliography. -

The Lays of Marie De France Mingling Voices Series Editor: Manijeh Mannani

The Lays of Marie de France mingling voices Series editor: Manijeh Mannani Give us wholeness, for we are broken. But who are we asking, and why do we ask? — Phyllis Webb National in scope, Mingling Voices draws on the work of both new and established poets, novelists, and writers of short stories. The series especially, but not exclusively, aims to promote authors who challenge traditions and cultural stereotypes. It is designed to reach a wide variety of readers, both generalists and specialists. Mingling Voices is also open to literary works that delineate the immigrant experience in Canada. Series Titles Poems for a Small Park Musing E. D. Blodgett Jonathan Locke Hart Dreamwork Dustship Glory Jonathan Locke Hart Andreas Schroeder Windfall Apples: The Kindness Colder Than Tanka and Kyoka the Elements Richard Stevenson Charles Noble The dust of just beginning The Metabolism of Desire: Don Kerr The Poetry of Guido Cavalcanti Translated by David R. Slavitt Roy & Me: This Is Not a Memoir kiyâm Maurice Yacowar Naomi McIlwraith Zeus and the Giant Iced Tea Sefer Leopold McGinnis Ewa Lipska, translated by Barbara Bogoczek and Tony Howard Praha E. D. Blodgett The Lays of Marie de France Translated by David R. Slavitt translated by David R.Slavitt Copyright © 2013 David R. Slavitt Published by AU Press, Athabasca University 1200, 10011 – 109 Street, Edmonton, ab t5j 3s8 978-1-927356-35-7 (paper) 978-1-927356-36-4 (pdf) 978-1-927356-37-1 (epub) A volume in Mingling Voices. issn 1917-9405 (print) 1917-9413 (digital) Cover and interior design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design. -

Critical Analysis of the Roles of Women in the Lais of Marie De France

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1976 Critical analysis of the roles of women in the Lais of Marie de France Jeri S. Guthrie The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Guthrie, Jeri S., "Critical analysis of the roles of women in the Lais of Marie de France" (1976). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1941. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1941 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE ROLES OF WOMEN IN THE LAIS OF MARIE DE FRANCE By Jeri S. Guthrie B.A., University of Montana, 1972 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1976 Approved by: Chairmah, Board of Exami iradua4J^ School [ Date UMI Number EP35846 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT OissHEH'tfttkffl Pk^islw^ UMI EP35846 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). -

Engl. 451/551 Syllabus

Spring 2009 ◆ Engl. 451/551 (#33874/35123), COMP-L 480 (34486) WMST 479 (#35656) TTh 3:30-4:45 ◆ HUM 108 Dr. Obermeier Uppity Medieval Women Office Hours: TTh 1:30-2:30, and by Appointment in HUM 321 and Voice Mail: 505.277.2930 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.unm.edu/~aobermei Mailbox on office door or in English Department Office via receptionist Required Texts Abelard and Heloise. Ed. William Levitan. Hackett, 2007. The Book of Margery Kempe. Ed. Lynn Staley. Norton, 2001. The Lais of Marie de France. Trans. Glyn S. Burgess and Keith Busby. Penguin 1986. Obermeier, Anita, and Gregory Castle. Guide to Style. 2005. On class webpage. Ovid, Heroides. Penguin, 1990. Pizan, Christine de. The Book of the City of Ladies. Penguin, 1999. Silence: A Thirteenth-Century French Romance. Ed. Sarah Roche-Mahdi. Michigan State UP, 1999. The Trial of Joan of Arc. Ed. Daniel Hobbins. Harvard UP, 2007. Class webpage: http://www.unm.edu/~aobermei/Eng451551/index451551.html Most all other readings are and/or will be put on eReserve: link on class webpage. Password = Pizan451. Hardcopy Reserve link for further research is also on class webpage. Course Requirements Undergraduates: Graduates: 1 4-5-page paper worth 10% 1 4-5-page paper worth 10% 1 8-10-page paper worth 25% 1 15-page paper & Literature Review worth 30% 1 In-class midterm worth 10% 1 In-class midterm worth 10% 1 In-class final worth 20% 1 In-class final worth 20% Oral Group Presentation worth 5% Oral Group Presentation worth 5% Written Responses worth 15% Written Responses worth 10% Class Participation worth 15% Class Participation worth 15% Grading is done on a standard 0-100 scale. -

Jean Gerson and the Debate on the Romance of the Rose

JEAN GERSON AND THE DEBATE ON THE ROMANCE OF THE ROSE Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski What was at stake in the debate on the Romance of the Rose? Why would a learned authoress, a famous theologian and a group of intel- lectual clerics spend untold hours either attacking or defending a work written in French that was at that point over a hundred years old? For the debaters nothing less was at stake than the function and power of literature in their society. Does vernacular literature have a moral responsibility toward its audience? This was one of the fundamental questions addressed by all the participants in the debate. Yet their opinions on the book’s value differed enormously. By its adversaries the Rose was seen as inciting husbands to domes- tic violence; as leading to bad morals and from there to heresy; as a book that destroys the very fabric of medieval society and should therefore be burned. By its supporters it was praised as a marvelous compendium teaching good morals and overflowing with the learn- ing of an almost divine theologian named Jean de Meun. Who was right, the rhodophiles or the rhodophobes?1 The Romance of the Rose was one of the most popular texts of the Middle Ages. Over two hundred manuscripts (many of them beau- tifully illuminated) and printed editions survive from the period between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries. The Rose was also an infinitely rich work, open to almost as many interpretations as there were readers.2 Composed by two different authors, Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun, the two quite distinct parts of the romance date from c. -

French (08/31/21)

Bulletin 2021-22 French (08/31/21) evolved over time by interpreting related forms of cultural French representation and expression in order to develop an informed critical perspective on a matter of current debate. Contact: Tili Boon Cuillé Prerequisite: In-Perspective course. Phone: 314-935-5175 • In-Depth Courses (L34 French 370s-390s) Email: [email protected] These courses build upon the strong foundation students Website: http://rll.wustl.edu have acquired in In-Perspective courses. Students have the opportunity to take the plunge and explore a topic in the Courses professor’s area of expertise, learning to situate the subject Visit online course listings to view semester offerings for in its historical and cultural context and to moderate their L34 French (https://courses.wustl.edu/CourseInfo.aspx? own views with respect to those of other cultural critics. sch=L&dept=L34&crslvl=1:4). Prerequisite: In-Perspective course. Undergraduate French courses include the following categories: L34 French 1011 Essential French I Workshop Application of the curriculum presented in French 101D. Pass/ • Cultural Expression (French 307D) Fail only. Grade dependent on attendance and participation. Limited to 12 students. Students must be enrolled concurrently in This course enables students to reinforce and refine French 101D. their French written and oral expression while exploring Credit 1 unit. EN: H culturally rich contexts and addressing socially relevant questions. Emphasis is placed on concrete and creative L34 French 101D French Level I: Essential French I description and narration. Prerequisite: L34 French 204 or This course immerses students in the French language and equivalent. Francophone culture from around the world, focusing on rapid acquisition of spoken and written French as well as listening Current topic: Les Banlieues. -

Eleanor of Aquitaine and 12Th Century Anglo-Norman Literary Milieu

THE QUEEN OF TROUBADOURS GOES TO ENGLAND: ELEANOR OF AQUITAINE AND 12TH CENTURY ANGLO-NORMAN LITERARY MILIEU EUGENIO M. OLIVARES MERINO Universidad de Jaén The purpose of the present paper is to cast some light on the role played by Eleanor of Aquitaine in the development of Anglo-Norman literature at the time when she was Queen of England (1155-1204). Although her importance in the growth of courtly love literature in France has been sufficiently stated, little attention has been paid to her patronising activities in England. My contribution provides a new portrait of the Queen of Troubadours, also as a promoter of Anglo-Norman literature: many were the authors, both French and English, who might have written under her royal patronage during the second half of the 12th century. Starting with Rita Lejeune’s seminal work (1954) on the Queen’s literary role, I have gathered scattered information from different sources: approaches to Anglo-Norman literature, Eleanor’s biographies and studies in Arthurian Romance. Nevertheless, mine is not a mere systematization of available data, for both in the light of new discoveries and by contrasting existing information, I have enlarged agreed conclusions and proposed new topics for research and discussion. The year 2004 marked the 800th anniversary of Eleanor of Aquitaine’s death. An exhibition was held at the Abbey of Fontevraud (France), and a long list of books has been published (or re-edited) about the most famous queen of the Middle Ages during these last six years. 1 Starting with R. Lejeune’s seminal work (1954) on 1. -

1 the Middle Ages

THE MIDDLE AGES 1 1 The Middle Ages Introduction The Middle Ages lasted a thousand years, from the break-up of the Roman Empire in the fifth century to the end of the fifteenth, when there was an awareness that a ‘dark time’ (Rabelais dismissively called it ‘gothic’) separated the present from the classical world. During this medium aevum or ‘Middle Age’, situated between classical antiquity and modern times, the centre of the world moved north as the civil- ization of the Mediterranean joined forces with the vigorous culture of temperate Europe. Rather than an Age, however, it is more appropriate to speak of Ages, for surges of decay and renewal over ten centuries redrew the political, social and cultural map of Europe, by war, marriage and treaty. By the sixth century, Christianity was replacing older gods and the organized fabric of the Roman Empire had been eroded and trading patterns disrupted. Although the Church kept administrative structures and learning alive, barbarian encroachments from the north and Saracen invasions from the south posed a continuing threat. The work of undoing the fragmentation of Rome’s imperial domain was undertaken by Charlemagne (742–814), who created a Holy Roman Empire, and subsequently by his successors over many centuries who, in bursts of military and administrative activity, bought, earned or coerced the loyalty of the rulers of the many duchies and comtés which formed the patchwork of feudal territories that was France. This process of centralization proceeded at variable speeds. After the break-up of Charlemagne’s empire at the end of the tenth century, ‘France’ was a kingdom which occupied the region now known as 2 THE MIDDLE AGES the Île de France. -

05.01.21, Heller-Roazen, Fortune's Faces

05.01.21, Heller-Roazen, Fortune's Faces Main Article Content The Medieval Review baj9928.0501.021 05.01.21 Heller-Roazen, Daniel. Fortune's Faces: The Roman de la Rose and the Poetics of Contingency. Series: Parallax. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003. Pp. xiii, 206. ISBN: 0-8018-7191-3. Reviewed by: Suzanne Conklin Akbari University of Toronto [email protected] Fortune's Faces is, in some ways, a difficult book to review, because it is not really written by a medievalist. This is in no way a criticism, for Heller-Roazen is in fact a highly skilled comparatist of a kind only rarely seen nowadays: he is comfortable in a range of vernacular and classical languages, and committed to unraveling the tangled relationship of philosophy and poetics rather than simply excavating a dusty corner of medieval culture. Heller- Roazen is probably best known for his intelligent translations of the work of Giorgio Agamben, but he has also written on subjects as diverse as the great library at Alexandria and aphasia in literature. His wide range of expertise, encompassing several languages and humanistic disciplines, truly makes him what used to be called a "Renaissance man," with the added dimension of his engagement with the political as well as the philosophical. It is necessary to have some sense of Heller-Roazen's scholarly perspective in order to assess the very real merits of Fortune's Faces. If the reader is looking for a reading of the Roman de la Rose in the context of the intellectual history of late thirteenth-century Paris, the book will disappoint. -

![Bernart De Ventadorn [De Ventador, Del Ventadorn, De Ventedorn] (B](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6126/bernart-de-ventadorn-de-ventador-del-ventadorn-de-ventedorn-b-1026126.webp)

Bernart De Ventadorn [De Ventador, Del Ventadorn, De Ventedorn] (B

Bernart de Ventadorn [de Ventador, del Ventadorn, de Ventedorn] (b Ventadorn, ?c1130–40; d ?Dordogne, c1190–1200). Troubadour. He is widely regarded today as perhaps the finest of the troubadour poets and probably the most important musically. His vida, which contains many purely conventional elements, states that he was born in the castle of Ventadorn in the province of Limousin, and was in the service of the Viscount of Ventadorn. In Lo temps vai e ven e vire (PC 70.30, which survives without music), he mentioned ‘the school of Eble’ (‘l'escola n'Eblo’) – apparently a reference to Eble II, Viscount of Ventadorn from 1106 to some time after 1147. It is uncertain, however, whether this reference is to Eble II or his son and successor Eble III; both were known as patrons of many troubadours, and Eble II was himself a poet, although apparently none of his works has survived. The reference is thought to indicate the existence of two competing schools of poetic composition among the early troubadours, with Eble II as the head and patron of the school that upheld the more idealistic view of courtly love against the propagators of the trobar clos or difficult and dark style. Bernart, according to this hypothesis, became the principal representative of this idealist school among the second generation of troubadours. The popular story of Bernart's humble origins stems also from his vida and from a satirical poem by his slightly younger contemporary Peire d'Alvernhe. The vida states that his father was either a servant, a baker or a foot soldier (in Peire's version, a ‘worthy wielder of the laburnum bow’), and his mother either a servant or a baker (Peire: ‘she fired the oven and gathered twigs’). -

Mouvance and Authorship in Heinrich Von Morungen

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Songs of the Self: Authorship and Mastery in Minnesang Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/87n0t2tm Author Fockele, Kenneth Elswick Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Songs of the Self: Authorship and Mastery in Minnesang by Kenneth Elswick Fockele A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German and Medieval Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Niklaus Largier, chair Professor Elaine Tennant Professor Frank Bezner Fall 2016 Songs of the Self: Authorship and Mastery in Minnesang © 2016 by Kenneth Elswick Fockele Abstract Songs of the Self: Authorship and Mastery in Minnesang by Kenneth Elswick Fockele Doctor of Philosophy in German and Medieval Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Niklaus Largier, Chair Despite the centrality of medieval courtly love lyric, or Minnesang, to the canon of German literature, its interpretation has been shaped in large degree by what is not known about it—that is, the lack of information about its authors. This has led on the one hand to functional approaches that treat the authors as a class subject to sociological analysis, and on the other to approaches that emphasize the fictionality of Minnesang as a form of role- playing in which genre conventions supersede individual contributions. I argue that the men who composed and performed these songs at court were, in fact, using them to create and curate individual profiles for themselves. -

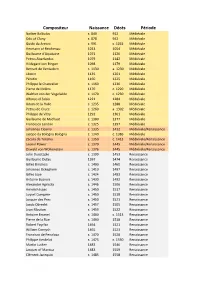

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus C

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus c. 840 912 Médiévale Odo of Cluny c. 878 942 Médiévale Guido da Arezzo c. 991 c. 1033 Médiévale Hermann of Reichenau 1013 1054 Médiévale Guillaume d'Aquitaine 1071 1126 Médiévale Petrus Abaelardus 1079 1142 Médiévale Hildegard von Bingen 1098 1179 Médiévale Bernart de Ventadorn c. 1130 a. 1230 Médiévale Léonin 1135 1201 Médiévale Pérotin 1160 1225 Médiévale Philippe le Chancelier c. 1160 1236 Médiévale Pierre de Molins 1170 c. 1220 Médiévale Walther von der Vogelwide c. 1170 c. 1230 Médiévale Alfonso el Sabio 1221 1284 Médiévale Adam de la Halle c. 1235 1288 Médiévale Petrus de Cruce c. 1260 a. 1302 Médiévale Philippe de Vitry 1291 1361 Médiévale Guillaume de Machaut c. 1300 1377 Médiévale Francesco Landini c. 1325 1397 Médiévale Johannes Ciconia c. 1335 1412 Médiévale/Renaissance Jacopo da Bologna Bologna c. 1340 c. 1386 Médiévale Zacara da Teramo c. 1350 c. 1413 Médiévale/Renaissance Leonel Power c. 1370 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance Oswald von Wolkenstein c. 1376 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance John Dunstaple c. 1390 1453 Renaissance Guillaume Dufay 1397 1474 Renaissance Gilles Binchois c. 1400 1460 Renaissance Johannes Ockeghem c. 1410 1497 Renaissance Gilles Joye c. 1424 1483 Renaissance Antoine Busnois c. 1430 1492 Renaissance Alexander Agricola c. 1446 1506 Renaissance Heinrich Isaac c. 1450 1517 Renaissance Loyset Compère c. 1450 1518 Renaissance Josquin des Prez c. 1450 1521 Renaissance Jacob Obrecht c. 1457 1505 Renaissance Jean Mouton c. 1459 1522 Renaissance Antoine Brumel c. 1460 c. 1513 Renaissance Pierre de la Rue c. 1460 1518 Renaissance Robert Fayrfax 1464 1521 Renaissance William Cornysh 1465 1523 Renaissance Francisco de Penalosa c.