Madrona Marsh Preserve and Nature Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Tanager

LosWestern Angeles Audubon Society | laaudubon.org Tanager On The COVER: Black Oystercatcher, Haematopus bachmani, hunting on the rocks at the Redondo Beach marina. Photo by Jamie Lowry CONTENTS ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER: 3 Tales of a Budding Naturalist Jamie F. Lowry was born and raised in a small town in southwestern 15 Conservation Conversation Michigan. After earning degrees from Michigan State University and the University of Michigan Law School, she relocated to Hermosa Los Angeles Audubon Society 16 Summer Camp 2016 Beach, California, and began practicing law with a large international P.O. Box 411301 law firm with offices in downtown Los Angeles. Some years later she started a new career as a full-time mother of two children, a Los Angeles, CA 90041-8301 18 Birds of the Season daughter and a son. She later combined motherhood with a part- www.losangelesaudubon.org time resumption of her legal career. She is now retired and (323) 876-0202 continues to live in Hermosa Beach. 20 Breeding Bird Atlas Goes to Print [email protected] She has always been fascinated with nature, wildlife and natural science, and she and her husband have been long-time supporters of 21 Interpreting Nature many environmental and conservation-related groups and causes. Board Officers & Directors She is currently active in volunteer work along those lines, and is a President Margot Griswold [email protected] certified California naturalist. She also enjoys travel, music, books Vice President David De Lange [email protected] 23 Young Birders, The Tricolored Blackbird and art. She frequently takes photographs while out in nature for her Treasurer Robert Jeffers [email protected] Past President Travis Longcore [email protected] own personal records and to share what she has observed with Directors at Large Nicole Lannoy Lawson 25 Monthly Program Presentations friends and family. -

2013-1 Winter

W i n t e r 2 0 1 3 MaMadrrona sMarsh Pre servMe and aNatuirel Ciennter g Alondra Park––Unnatural Place for a Natural Garden Jeanne Bellemin, Professor of Zoology, El Camino College* Over the past 14 years my students and I have created a rather unusual native garden on a very unnatural island. The Alondra Park Island Native Plant Garden is thriving with the winter rains and 2012 improvements. This past year we have painted the proud garden shed built by Max Pena and his LBCC and ECC construction students and funded by the South Coast Chapter of CNPS. Another improvement was the removal by Carson Animal Control of dozens of hungry rabbits which necessitated the fencing of most of the native plants. Now that we are down to only two rabbits we are removing much of the unsightly fencing so that our natives may grow and shape themselves as they might naturally. Continued on page 2. Annual Meeting of the Friends of Madrona Marsh When? Sunday, January 27 starting at 3 p.m. Where? Madrona Marsh Nature Center Meeting Room 3201 Plaza del Amo, Torrance, CA 90503 [NOTE: Come early for Tours of our New Restoration Areas from 2- 2:45 p.m.] Election of 4 Members of Board of Directors • Jeanne Bellemin • Mary Garrity • Carol Roelen • Bobbie Snyder Annual Reports from Manager and Naturalist, Tracy Drake, and from Friends Vice President, Suzan Hubert DOUBLE-HEADER PROGRAM: 1. New Restoration Programs-––Dan Portway will bring us up to date on several new restoration areas on the Preserve and a new approach we are taking. -

CPY Document

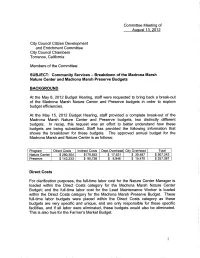

Committee Meeting of AugustAUQust 13.13, 2012 City Council Citizen Development and Enrichment Committee City Council Chambers Torrance, California Members of the Committee: SUBJECT: Community Services - Breakdown Breakdown of of the the Madrona Madrona Marsh Marsh Nature Center and Madrona Marsh Preserve Budgets BACKGROUND At thethe May 8,8, 20122012 Budget Hearing, staffstaff werewere requestedrequested to bring bring back a A break-out break-out of the the Madrona Madrona Marsh Marsh Nature Nature Center Center and and Preserve Preserve budgets budgets in order order to to explore explore budget efficiencies. At the May May 15, 15, 2012 2012 Budget Budget Hearing, Hearing, staff staff provided provided Aa complete complete break-out break-out of the Madrona Marsh Nature Nature Center Center and and Preserve Preserve budgets, budgets, two two distinctly distinctly different different budgets. In In recap, recap, this this request was an an effort effort to betterbetter understandunderstand howhow these budgets are being being subsidized. subsidized. Staff has has provided provided the the following following information information that that shows the breakdown forfor these budgets. The The approved approved annual annual budget budget for the the Madrona Marsh and Nature Nature Center Center is is as follows: Program Direct Costs Indirect Costs Deot. OverheadOverhead Citv Ovèrhead Overhead Total Nature Center $ 280,304 $178,822 $ 17,631 17.631 $ 30,487 $ 507,243 Preserve $ 142,233 $ 90,738 90.738$ 8,946 8.946 $ 15,470 15,470 $ 257,387 Direct Costs For clarification purposes, the full-time labor cost for the Nature Nature Center Center Manager Manager is is loaded within thethe Direct Direct Costs category category for the the Madrona Madrona Marsh Marsh Nature Nature Center Center Budget; and the the full-time full-time labor cost for the Lead Lead Maintenance Maintenance Worker Worker is is loaded loaded within the Direct Direct Costs category for the Madrona Madrona Marsh Preserve Budget.Budget. -

Notice of the Regular Meeting of the Board Of

NOTICE OF THE REGULAR MEETING OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE LOS ANGELES COUNTY WEST VECTOR & VECTOR-BORNE DISEASE CONTROL DISTRICT March 12, 2020 6750 Centinela Ave. Culver City, CA 90230 7:30 p.m. Los Angeles County West Vector & Vector-Borne Disease Control District 6750 Centinela Avenue, Culver City, California 90230 (310) 915-7370 ext. 223 Email: [email protected] BOARD OF TRUSTEES President ROBERT SAVISKAS JAY GARACOCHEA Executive Director Culver City Vice President CHAD BLOUIN West Hollywood BILL AILOR Palos Verdes Estates BARBARA BARSOCCHINI Malibu JAMES R. BOZAJIAN NOTICE OF THE NEXT REGULAR MEETING Calabasas S.W. DiSALVO OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES Beverly Hills JIM FASOLA OF THE LOS ANGELES COUNTY WEST Hermosa Beach VECTOR & VECTOR-BORNE CONTROL JOHN FRAZEE Manhattan Beach DISTRICT JIM GAZELEY Lomita MARY DRUMMER Redondo Beach March 12, 2020 6750 Centinela Ave. NANCY GREENSTEIN Santa Monica Culver City, CA 90230 7:30 p.m. MIKE GRIFFITHS Torrance CHERYL MATTHEWS Inglewood JAMES OSBORNE Lawndale ELIZABETH SALA Rancho Palos Verdes OLIVIA VALENTINE Hawthorne STEVE ZUCKERMAN Rolling Hills Estates LOS ANGELES COUNTY WEST VECTOR & VECTOR-BORNE DISEASE CONTROL DISTRICT REGULAR MEETING OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES (310) 915-7370 ext. 223 AGENDA 6750 Centinela Ave. Culver City, CA 90230 7:30 p.m. NOTICE TO THE PUBLIC Residents who live or own property within the District who wish to comment on any of the listed agenda items are requested to fill out the “Request to Comment on Listed Agenda Items” form. This form may be obtained from the Executive Director and should be returned to him prior to the beginning of the regular meeting. -

G Ardens , W Ildlands and C Onservation in T Imes of D

SUMMER QUARTER 2016 rtemisia NEWSLETTER OF THE SOUTH COAST CHAPTER OF THE CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY AG ARDENS , W ILDLANDS AND C ONSERVATION IN T I M E S O F D ROUGHT By Connie Vadheim, Friends of Gardena Willows Wetland Preserve Drought is having a major effect on local wildlands. The signs are everywhere: trees are succumbing to the combined stresses of drought and insects. Shrubs and perennials are blooming early – or not at all. Seed reproduction is well below normal in many parts of Los Angeles County. It’s tough times for plants and the animals that depend on them. Gardens play an important role in times of drought. Supplemental irrigation spares native plant gardens the worst impacts, and the consequences for both flora and fauna are dramatic. To convince yourself, get out and look. Compare the bird and insect fauna in wild lands and gardens. You’ll be hard pressed to find many ‘common’ species in the wild this year. In times of drought, native plant gardens function as mini-preserves; they provide key habitat unavailable elsewhere. They are particularly important for insects, including the native pollinators. Gardens also play an essential conservation role by providing seeds, plants and plant materials for restoration and other uses. The growing interest in the edible, medicinal and other uses of native plants is heartening. But wildland collecting could overtake our natural resources, particularly in times of drought. As CNPS members, we are well aware of the rarity of some local plant species. Over-collecting of rare – and even more common – plants is a real possibility in times of drought. -

Marsh Mailing-09/06

Fall2008 MadronaMarshPreserveandNatureCenter ANewBuzz InOur Insect Collection ––Jeanne Bellimin In the late 1970s when the Nature Center was merely a trailer run by Walt Wright, Norm Hogg and I donated a drawer of insects from our collection to Hide Kato, who spent more than 110 hours this past summer helping to be on display and to be carried to events. organize and refurbish the Preserve’s insect collection, seeks new Now, after 30 years those insects were specimens for the collection. rather dusty, rumpled and broken. In 1997 a wonderful wet collection (i.e., stored in alcohol) of aquatic life, including many teacher in Santa Ana, and is currently serving as insects and other invertebrates found in the Marsh, a Captain in the National Guard. was completed by Mark Angelos and stored in the Curation Lab. This year I had a very interesting and ener- getic group in my Field Entomology class, two of In the Fall of 2004 a former Entomology stu- whom want to go on in the field of entomology. I dent of mine, Duminda Wijayaratna, created a very thought it would be good experience for Hide Kato attractive new two-drawer collection as part of an and Sanson Lin to combine the old collections at Environmental Restoration Class project. the Nature Center and build a new collection by adding specimens from the El Camino College stu- Last December the Friends of Madrona dents and newly collected specimens from the Marsh received a generous $1000 donation from Madrona Marsh. the Medina Trust, in the name of Howard Medina, to refurbish the insect collections at the Nature Hide Kato has spent more than 110 hours Center. -

Appendices for MMP Biological Inventory Final Report

9. APPENDICES Appendix A1. Minutes of meeting with long-time residents, Feb. 16, 2010 Notes on the meeting with long-term resident Friends of Madrona Marsh : Jane Nishimura, Jack Knapp, Shirley Turner, and Ruth McConnell, and Tracy Drake [TD], conducted by Dan Cooper [DSC] & Emile Fiesler [EF]. (Notes in brackets are clarifications by TD/EF/DSC) 1. Jack Knapp: (Jack has lived in Torrance since 1958, near the intersection of Crenshaw Boulevard and Sepulveda Boulevard.) In his neighborhood, he has observed: * Coyotes * Gray "Desert" Fox * Red Fox, and their dens & pups * Jackrabbits and Cottontail rabbits in area, but not on Preserve * Norway Rats, in association with restaurants * "Meadow Mice" * Quail, but not for a long time * Ringneck Snakes [= Diadophis punctatus ] * Rattlesnakes: observed by "old-timers" Jack spoke with in past; still on PV * Toads, in his yard, which were mainly active at night; many became traffic victims * Lizards; commonly seen on walls, etc., in neighborhood. In the area that is now the Preserve, he has observed: * Bats: inside a fenced section (of the Kelt area) in between stacked railroad ties lived batsand their "joeys" (= "pups"); they would stream out at night [= Mexican free- tailed bat? (DSC); which are common in urban Los Angeles area, incl. Downtown L.A./L.A. River]. Tracy said that Jack was the last person to see bats on the Preserve. * Red Squirrels [= eastern fox squirrel; noted "red tails"] * "Field Mice" [probably Mus musculus , DSC] * Cliff Swallows (couldn't recall where they nested) * Western Meadowlark: hundreds of them * Swimming snake in the Sump [could be Calif. -

Macro-Invertebrate Biodiversity of a Coastal Prairie with Vernal Pool Habitat

Biodiversity Data Journal 4: e6732 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.4.e6732 General Article Macro-invertebrate Biodiversity of a Coastal Prairie with Vernal Pool Habitat Emile Fiesler‡§, Tracy Drake ‡ Bioveyda, Torrance, California, United States of America § Manager, Madrona Marsh Preserve, Torrance, California, United States of America Corresponding author: Emile Fiesler ([email protected]) Academic editor: Benjamin Price Received: 01 Oct 2015 | Accepted: 30 Mar 2016 | Published: 27 Apr 2016 Citation: Fiesler E, Drake T (2016) Macro-invertebrate Biodiversity of a Coastal Prairie with Vernal Pool Habitat. Biodiversity Data Journal 4: e6732. doi: 10.3897/BDJ.4.e6732 Abstract Background The California Coastal Prairie has the highest biodiversity of North America's grasslands, but also has the highest percentage of urbanization. The most urbanized part of the California Coastal Prairie is its southernmost area, in Los Angeles County. This southernmost region, known as the Los Angeles Coastal Prairie, was historically dotted with vernal pools, and has a unique biodiverse composition. More than 99.5% of its estimated original 95 km2 (23,475 acres), as well as almost all its vernal pool complexes, have been lost to urbanization. The Madrona Marsh Preserve, in Torrance, California, safeguards approximately 18 hectares (44 acres) of Los Angeles Coastal Prairie and includes a complex of vernal pools. Its aquatic biodiversity had been studied, predominantly to genus level, but its terrestrial macro-invertebrates were virtually unknown, aside from butterfly, dragonfly, and damselfly observations. © Fiesler E, Drake T. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Marsh Mailing-09/06

Summer2010 MadronaMarshPreserveandNatureCenter SouthwestCornerGetsaNewFace ––Bill Arrowsmith new sign was installed in this southwest triangle– match- The southwest corner of the Madrona Marsh Pre- ing the other three corners of the Preserve. All that re- serve, the so-called “Chevron Corner” property, which mains now is to landscape the area with California Na- was donated to the City of Torrance in the summer of tive Plants. 2008 is finally getting a new face. Gone is the old chain- link fencing with its unsightly (but informative) commu- nity posters. Note to Marshans: The City Council did form a committee to investigate the possibility of installing an electronic sign along Sepulveda, at the east edge of In May, workers extended the same steel fencing the corner property. The idea was/is to use the elec- that girds the rest of the Preserve across the corner tronic sign to take the place of all the community post- property (see photo above), leaving a triangular por- ers that used to ‘adorn’ the chain-link fence. The com- tion outside the fence (see photo at right). In June a “Corner” continues on page 4. GettingtotheBottomofThings ––Bill Arrowsmith For many years, going back to the days when That year, the onset of the dry summer season enabled Walt Wright was the Preserve’s Naturalist, we have the Marsh to ‘clean up its own act,’ saving the City thou- been plagued by intermittent, but very severe, prob- sands of dollars. Efforts to pinpoint the source of pollu- lems near Drain #1, which is just north of the south- tion have been inconclusive. -

Marsh Mailing-09/06

Spring2008 MadronaMarshPreserveandNatureCenter CallsintheNight The day had been long and its last light was quickly flooded my ears! The fading into night. Tired, I drove to the Maple Sepulveda frog songs had begun Sump—I needed to check the water level after a day of and they were so loud pumping water up to the Preserve. In the half-light of I could no longer hear the evening, walking along the uneven gravel road my the cars driving along feet kicked up pebbles. I watched them scatter ahead of Sepulveda! Over- me. Actually the pebbles seemed to hop on ahead of come with joy, I started me––just like frogs. I began wondering about the frogs using my cell phone to ––had the last two years of drought caused them to die call people. I just had off? Would there be any this year? I had only heard a to share the momen- few to date––the chorus I had heard a few days earlier tous occasion! With seemed quiet and far away. And I had found so many the speakerphone dead ones over the past six-months that a real amount turned to full volume, of worry had built up in me. I yelled, “Hey, can you hear that? They’re Our Pacific Tree Frog The water level was fine. I shut down the pump for back – they have sur- Photo by Jack Ludwick. the night, and headed back along the road toward my vived!” ––T.D. car. All of a sudden, an overwhelming number of calls TheProgramsofJanuaryandFebruary I have received a few calls asking why there has a long story short, four of the seven Madrona Marsh Staff not been a “Month in Review” for several months. -

Starlight Magic, October 1, 2011

Midsummer2011 MadronaMarshPreserveandNatureCenter WhataMagicalNightItWas-andWillBe! StarlightMagic,October1,2011 If you’re a regular reader of the Marsh Mailing, Ah, but if you were not able to attend last year, reflect back two issues to the Winter 2010/2011 news- fear not, for you will soon get a second chance. And, letter. You remember––the from the planning I’ve seen one with pages of pictures of thus far by Suzan Hubert, happy faces? And we’re not chief sorcerer, and her band talking ‘emoticons’ here. of merry magicians, includ- These were giant grins on the ing Mary Garrity and faces of all the attendees of Bobbie Snyder, this year’s last autumn’s inaugural event will be even better–– fundraising event on the Pre- if that’s possible. serve, “Moonlight Magic, For starters, this 2010,” including Mayor Scotto year’s Magic evening prom- and the entire Torrance City ises to be even more ro- Council. Hopefully, you were mantic. With only a faint among the over 200 who at- sliver of moon on Saturday, tended last year, and the pic- October 1, the Magic this tures brought back pleasant year will be provided by memories of good music, good Beth Shibata’s Signature Starlight Magic artwork is one of the starlight. For the less ro- fantastic prizes offered at the event. food, good wine and lots of mantically inclined, Paul merriment for a very good cause: Securing the future Livio will have telescopes set up to view the heavens. of the Madrona Marsh Preserve. “Magical” continues on page 11 our wonderful SEASONAL Marsh evaporated on Au- SpecialMidsummerIssue gust 17, two weeks after the WNV report. -

Marshmail-Summer'19 Color

Summer 2019 MarshMadrona Marsh Preserve Mailing and Nature Center Marsh Mailing is also available in full color at www.friendsofmadronamarsh.com* The Friends Invest in the Future by Suzan Hubert, FOMM President On June 12, 2019 the Friends of Madrona Marsh awarded our very first Environmental Leadership Scholarship. Our recipient is Joshua Minoru Matsuda. Joshua was an Advanced Restoration Crew member at the Marsh; he is a North High graduate and will be a freshman at UCLA this fall. Joshua completed 84 hours of volunteer work at the Marsh. At North High he earned honors in Biology and Chemistry with A Shown is Joshua Matsuda, North High School senior and winner of the grades and he took Advanced first Environmental Scholarship awarded by the Friends. Joshua is surrounded here by several Board members at the presentation. Placement courses in Chemistry and Environmental studies, 719 in Torrance Joshua planted trees at earning A grades there as well. While earning his Eagle Scout Award from Troop “Scholarship” continued on page 2 Opportunity Knocks--Twice! That’s right. This summer you will have every Thursday, for the entire month, and on TWO opportunities to support the Friends, in July 18th, we’ll all howl at the (nearly) full moon. two successive months, and both are Come, and bring your friends! (See flyer on guaranteed to be barrels of fun. Page 3. NOTE: July 4 hours - Noon-6 p.m.) AUGUST – Join us at the Nature Center on JULY – Every Thursday night in July (4, 11, August 17th for “Walkin’ Thru Time”, our summer 18, 25) the Friends will be the featured fundraiser and grand re-opening of our newly environmental partner at Smog City Brewing remodeled Nature Center.