Reducing Child Marriage a Model to Scale up Results in India New Delhi 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDIA YEAR BOOK-2017 Good Luck!

INDIA YEAR BOOK - 2017 INDIA YEAR BOOK-2017 Dear Students, With the focus on the provision of best study material to our students, Rau’s IAS Study Circle is innovatively presenting the voluminous INDIA YEAR BOOK-2017 in a very concise and lucid manner. Through this, efforts have been taken to circulate the best synopsis extracted from the Year Book-2017 for the benefit of the students. The abstract has been designed to present contents of the year book in most user-friendly manner. All the major and important points are given in bold and highlighted. The content is also supported by figures and pictures as per the requirement. The content has been chosen and compiled judiciously so that maximum coverage of all the relevant and significant material is presented within minimum readable pages. The issue titled ‘INDIA YEAR BOOK-2017 will be covering the following topics: 1. Land and the People 16. Health and Family Welfare 2. National Symbols 17. Housing 3. The Polity 18. India and the World 4. Agriculture 19. Industry 5. Culture and Tourism 20. Law and Justice 6. Basic Economic Data 21. Labour, Skill Development and Employment 7. Commerce 22. Mass Communication 8. Communications and Information Technology 23. Planning 9. Defence 24. Rural and Urban Development 10. Education 25. Scietific and Technological Developments 11. Energy 26. Transport 12. Environment 27. Water Resources 13. Finance 28. Welfare 14. Corporate Affairs 29. Youth Affairs and Sports 15. Food and Civil Supplies By providing this, the Study Circle hopes that all the students will be able to make the best use of it as a ready reference material and allay their fears of perusing and cramming the entire year book. -

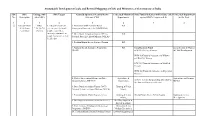

Sustainable Development Goals and Revised Mapping of Csss and Ministries of Government of India

Sustainable Development Goals and Revised Mapping of CSSs and Ministries of Government of India SDG SDG Linkage with SDG Targets Centrally Sponsored /Central Sector Concerned Ministries/ State Funded Schemes (with Scheme code) Concerned Department No. Description other SDGs Schemes (CSS) Departments against SDG's Targets (col. 4) in the State 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 ① End poverty in SDGs 1.1 By 2030, eradicate 1. Mahatma Gandhi National Rural RD all its forms 2,3,4,5,6,7,8, extreme poverty for all Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) everywhere 10,11,13 people everywhere, currently measured as 2. Deen Dayal Antyodaya Yojana (DAY) - RD people living on less than National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM) $1.25 a day 3. Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana - Gramin RD 4. National Social Assistance Programme RD Social Security Fund Social Secuity & Women (NSAP) SSW-03) Old Age Pension & Child Development. WCD-03)Financial Assistance to Widows and Destitute women SSW-04) Financial Assistance to Disabled Persons WCD-02) Financial Assistance to Dependent Children 5. Market Intervention Scheme and Price Agriculture & Agriculture and Farmers Support Scheme (MIS-PSS) Cooperation, AGR-31 Scheme for providing debt relief to Welfare the distressed farmers in the state 6. Deen Dayal Antyodaya Yojana (DAY)- Housing & Urban National Urban Livelihood Mission (NULM) Affairs, 7. Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana -Urban Housing & Urban HG-04 Punjab Shehri Awaas Yojana Housing & Urban Affairs, Development 8. Development of Skills (Umbrella Scheme) Skill Development & Entrepreneurship, 9. Prime Minister Employment Generation Micro, Small and Programme (PMEGP) Medium Enterprises, 10. Pradhan Mantri Rojgar Protsahan Yojana Labour & Employment Sustainable Development Goals and Revised Mapping of CSSs and Ministries of Government of India SDG SDG Linkage with SDG Targets Centrally Sponsored /Central Sector Concerned Ministries/ State Funded Schemes (with Scheme code) Concerned Department No. -

MPDC 405 Women Empowerment Schemes

Government Schemes and Policies for Girl Child and Women Empowerment The future of a country hinges on ensuring the generations to come are adequately represented, qualified and able to carry the mantle of development. As a nation, our past is rife with gender inequality but aiming to rectify that situation; the Government is taking steps to empower, educate and uplift the girl child. Central and State Government policies and schemes that are targeted at improving the lives of girl child in India are mentioned below 1. Beti Bachao Beti Padhao Scheme 2. One Stop Centre Scheme 3. Women Helpline Scheme 4. UJJAWALA : A Comprehensive Scheme for Prevention of trafficking and Rescue, Rehabilitation and Re-integration of Victims of Trafficking and Commercial Sexual Exploitation 5. Working Women Hostel 6. Ministry approves new projects under Ujjawala Scheme and continues existing projects 7. SWADHAR Greh (A Scheme for Women in Difficult Circumstances) 8. NARI SHAKTI PURASKAR 9. Awardees of Stree Shakti Puruskar, 2014 & Awardees of Nari Shakti Puruskar 10. Awardees of Rajya Mahila Samman & Zila Mahila Samman 11. Mahila police Volunteers 12. Mahila Shakti Kendras (MSK) 13. NIRBHAYA (source- https://wcd.nic.in/schemes-listing/2405) The Ministry of Women and Child Development is implementing various schemes/programmes for empowerment of women and development of children across the country. The details of those schemes are as follows: For Women empowerment: Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY), {erstwhile Maternity Benefit Programme} has been contributing towards better enabling environment by providing cash incentives for improved health and nutrition to pregnant and nursing mothers. Scheme for Adolescent Girls aims at girls in the age group 11-18, to empower and improve their social status through nutrition, life skills, home skills and vocational training Pradhan Mantri Mahila Shakti Kendra scheme, promote community participation through involvement of Student Volunteers for empowerment of rural women. -

DISTRICT-LEVEL STUDY on CHILD MARRIAGE in INDIA What Do We Know About the Prevalence, Trends and Patterns?

DISTRICT-LEVEL STUDY ON CHILD MARRIAGE IN INDIA What do we know about the prevalence, trends and patterns? PADMAVATHI SRINIVASAN NIZAMUDDIN KHAN RAVI VERMA International Center for Research on Women (ICRW), India DORA GIUSTI JOACHIM THEIS SUPRITI CHAKRABORTY United Nations International Children’s Educational fund (UNICEF), India International Center for Research on Women ICRW where insight and action connect 1 1 This report has been prepared by the International Center for Research on Women, in association with UNICEF. The report provides an analysis of the prevalence of child marriage at the district level in India and some of its key drivers. Suggested Citation: Srinivasan, Padmavathi; Khan, Nizamuddin; Verma, Ravi; Giusti, Dora; Theis, Joachim & Chakraborty, Supriti. (2015). District-level study on child marriage in India: What do we know about the prevalence, trends and patterns? New Delhi, India: International Center for Research on Women. 2 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The International Center for Research on Women (ICRW), New Delhi, in collaboration with United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), New Delhi, conducted the District-level Study on Child Marriage in India to examine and highlight the prevalence, trends and patterns related to child marriage at the state and district levels. The first stage of the project, involving the study of prevalence, trends and patterns, quantitative analyses of a few key drivers of child marriage, and identification of state and districts for in-depth analysis, was undertaken and the report prepared by Dr. Padmavathi Srinivasan, with contributions from Dr. Nizamuddin Khan, under the strategic guidance of Dr. Ravi Verma. We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Ms. -

MPPSC PRELIMS the Only Comprehensive “CURRENT AFFAIRS” Magazine of “MADHYA PRADESH”In “ENGLISH MEDIUM”

MPPSC PRELIMS The Only Comprehensive “CURRENT AFFAIRS” Magazine of “MADHYA PRADESH”in “ENGLISH MEDIUM” National International MADHYA CURRENT Economy PRADESH MP Budget Current Affairs AFFAIRS MP Eco Survey MONTHLY Books-Authors Science Tech Personalities & Environment Sports OCTOBER 2020 Contact us: mppscadda.com [email protected] Call - 8368182233 WhatsApp - 7982862964 Telegram - t.me/mppscadda OCTOBER 2020 (CURRENT AFFAIRS) 1 MADHYA PRADESH NEWS Best wishes on International day of Older Persons Chief Minister Shri Shivraj Singh Chouhan has extended his best wishes on the International Day of Older Persons. He said that the elderly or senior persons have life experiences. They have the capacity to resolve many complicated problems. The biggest thing is that our elders have the qualities of patience, humility, ability, decision making and above all, the acquired knowledge that can give a direction to the society. Our youth must respect the elders. Their teachings must be imbibed in our lives. Chief Minister said that the elders are our heritage. Many legal provisions have been made for their honour and protection. Chief Minister has extended his best wishes to all senior citizens and elders on Senior Citizens day. Photos telling the story of Corona period Chief Minister Shri Shivraj Singh Chouhan today awarded the winners of the state level photo contest based on Covid-19 in a programme organized at Manas Bhawan and congratulated the photographers. Also inaugurated an exhibition of photographs clicked by press photographers of the state during the Corona period. Chief Minister Shri Chouhan said that the creativity of the photographers during Covid-19 crisis is apparent in this exhibition. -

Submission to the HRC on the Situation of Child, Early, and Forced Marriages in India

Submission to the HRC on the Situation of Child, Early, and Forced Marriages in India Submission made by KHUSHI-INDIA “An initiative of concerned individuals -researchers and activists- to improve health outcomes for all with a focus on marginalised and socially excluded persons”. Writing and review team include- Sai Jyothirmai Racherla; Kaushlendra Kumar; Dr. Vivek Khurana; Jaspreet Kaur; Abha Mishra; Dipi Rani Das; and Narendra Sekhar. Correspondence to Sai Jyothirmai Racherla, [email protected] and [email protected] The United Nations Human Rights Council, on September 27, 2013 adopted a resolution on strengthening efforts to prevent and eliminate child, early and forced marriage: challenges, achievements, best practices and implementation gaps. This resolution was adopted at the Twenty-fourth session and the office of High commissioner was requested to prepare a report to guide a panel discussion at the twenty-sixth session, on the challenges, achievements, best practices, and implementation gaps for preventing and eliminating child marriage. This first-ever resolution on child, early and forced marriage adopted at the Human Rights Council was co-sponsored by 107 countriesi and India with the largest number of child brides, (24 million representing 40 % of the world 60 million child marriages) has not signed this resolution.iiiii Though India has not signed this particular resolution but Government of India is a signatory to several international human rights conventions including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the Conventions on the Rights of the Child and international conferences such as the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) which illustrates Government’s commitment to protect the rights of children and particularly address the issue of child marriage. -

The Upholding and Downfall of Child Marriage in India”

Phi Alpha Theta Pacific Northwest Conference, 8–10 April 2021 Amanda Mills, Western Washington University, undergraduate student, “Before Menstruation: The Upholding and Downfall of Child Marriage in India” Abstract: This paper will cover the roots of the tradition of child marriage in India through the British colonial period all the way to the 1980s. This paper will attempt to dissect the economic, social, and philosophical reasonings for child marriage. Particular focus will be placed on the time of British colonial rule because that was a time of both exploitation and reform in child marriage laws. This paper will explore the language that surrounded the discourses on child marriage, from both the British colonists and the Indian detractors. This timeline will follow the legislative action that reformed child marriage laws, and show how active Indian natives, particularly Indian women, were in the changes. This paper will show both how the practice was phased out, yet never completely removed. Citing census figures as late as the 1980s, it will show how child bride deals are/were still occurring. While explaining the psychological and physiological ramifications of marrying off a child at such a young age, a pattern will emerge that shows how gendered the practice was. This will explain were this practice falls into the discussion of gender in history. It will also examine where gender falls into the discussion of subaltern studies. Before Menstruation-The Upholding and Downfall of Child Marriage in India Amanda Mills Western Washington University Undergraduate Studying the facets of how gender and sexuality are discussed and viewed in India is a vital piece of historical research. -

Urban Development in India: a Special Focus Public Finance Newsletter

Urban development in India: A special focus Public Finance Newsletter Issue XI March 2016 In this issue 2 Feature article 10 Pick of the quarter 20 Round the corner 22 Potpourri 24 PwC updates Knowledge is the only instrument of production that is not subject to diminishing returns. J M Clark Dear readers, ‘Round the corner’ provides news updates in the area of government finances and policies across the The above quotation from the globe and key paper releases in the public finance American economist still domain during the recent months, along with holds true. Knowledge reference links. The ‘Our work’ section presents a increases by sharing and our mid-term review of the Support Program for Urban initiative to share knowledge, Reforms (SPUR), Bihar, which was conducted by views and experiences in the our team for the Department for International public finance domain Development (DFID). SPUR is a six-year through this newsletter has given us returns in the programme being implemented by the Government form of readers and contributors from across the of Bihar in partnership with DFID in 29 urban local globe. In continuation with our efforts in this bodies of Bihar. direction, I welcome you to the eleventh issue of the Public Finance Newsletter. I would like to thank you for your overwhelming support and response. Your suggestions urge us to The feature article in this issue aims to delve continuously improve this newsletter to ensure deeper into India’s urban development agenda. effective information sharing. Last year, we witnessed the launch of new missions such as Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban We would like to invite you to contribute and share Transformation (AMRUT), which replaced the your experiences in the public finance space with Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission us. -

Body of Knowledge Improving Sexual & Reproductive Health for India’S Adolescents 2 Body of Knowledge USAID

Body of Knowledge Improving Sexual & Reproductive Health for India’s Adolescents 2 Body of Knowledge USAID The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is the United States federal government agency that provides economic development and humanitarian assistance around the world in support of the foreign policy goals of the United States. USAID works in over 100 countries around the world to promote broadly shared economic prosperity, strengthen democracy and good governance, protect human rights, improve global health, further education and provide humanitarian assistance.This report is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of Dasra and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States government. KIAWAH TRUST The Kiawah Trust is a UK family foundation that is committed to improving the lives of vulnerable and disadvantaged adolescent girls in India. The Kiawah Trust believes that educating adolescent girls from poor communities allows them to thrive, to have greater choice in their life and a louder voice in their community. This leads to healthier, more prosperous and more stable families, communities and nations. PIRAMAL FOUNDATION Piramal Foundation strongly believes that there are untapped innovative solutions that can address India’s most pressing problems. Each social project that is chosen to be funded and nurtured by the Piramal Foundation lies within one of the four broad areas - healthcare, education, livelihood creation and youth empowerment. The Foundation believes in developing innovative solutions to issues that are critical roadblocks towards unlocking India’s economic potential. -

Towards Ending Child Marriage

TOWARDS ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE HAQ: Centre for Child Rights has been addressing the issue of child marriage since 2009, when the Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India asked HAQ to write a handbook for the implementation of the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006. However, it was only in 2012 that HAQ began its work on the ground to address prevention of child marriages through direct intervention. This is being undertaken in partnership in three states- with MV Foundation in Telangana (2012-2015); Jabala Action Research Organisation in West Bengal (2012-to present) and with Mahila Jan Adhikar Samiti, Rajasthan (2015- to present). Child Marriage is an age-old custom in India. It has Roza Khatun from Murshidabad, West Bengal is continued despite social reform movements and pursuing B.A. Honours in Physical Education and is legislations against it. Over the years, along with the captain of the Football Team. She has managed culture “safety of girls”, “having to pay lower dowry to fight and escape being married off at 15 years. But for younger girls” have become additional reasons hers is a saga of struggle that continues. Her parents given to justify early marriage. have attempted to get her married five times but Roza has refused each time. She sought help from the local Child marriage has now come to be recognised as a government officials and the police who counselled violation of all human rights of children. While it has severe health and education implication, what has her parents. While she could fight her own battle often not been addressed enough is the aspect of the she failed to save her younger sister was married off child’s violation of the right to protection. -

Child Marriage and Early Child-Bearing in India: Risk Factors and Policy Implications

Policy Paper 10 Child Marriage and Early Child-bearing in India: Risk Factors and Policy Implications Jennifer Roest September 2016 The author Jennifer Roest is a Qualitative Research Assistant at Young Lives. Her research focuses on the themes of gender, inequality, poverty, youth and adolescence. Acknowledgements The author is grateful to the children, families and other community members who participate in Young Lives research. Special thanks are also due to Renu Singh, Sindhu Nambiath, Paul Dornan, Jo Boyden, Frances Winter, and Kirrily Pells for their expert comments and support, and to Patricia Espinoza and Abhijeet Singh for their quantitative data analysis and advice. Acknowledgment is also due to the many Young Lives researchers whose publications have contributed to this paper. Finally, we would like to thank the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF) for their funding towards the research and policy programme on child marriage in India (2015-18). About Young Lives Young Lives is an international study of childhood poverty, following the lives of 12,000 children in four countries (Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam) over 15 years. www.younglives.org.uk Young Lives is funded by UK aid from the Department for International Development (DFID) and co-funded by Irish Aid from 2014 to 2016. The views expressed are those of the author(s). They are not necessarily those of, or endorsed by, Young Lives, the University of Oxford, DFID or other funders. Young Lives Policy Paper 9, September 2016 © Young Lives Young Lives Policy Paper 10 Page 3 Contents The author 2 Acknowledgements 2 Summary 4 1. -

Ending Impunity for Child Marriage in India: NORMATIVE and IMPLEMENTATION GAPS MISSION and VISION

POLICY BRIEF Ending Impunity for Child Marriage in India: NORMATIVE AND IMPLEMENTATION GAPS MISSION AND VISION The Center for Reproductive Rights uses the law to advance reproductive freedom as a fundamental human right that all governments are legally obligated to protect, respect, and fulfill. Reproductive freedom lies at the heart of the promise of human dignity, self-determination, and equality embodied in both the U.S. Constitution and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Center works toward the time when that promise is enshrined in law in the United States and throughout the world. We envision a world where every woman is free to decide whether and when to have children; where every woman has access to the best reproductive healthcare available; where every woman can exercise her choices without coercion or discrimination. More simply put, we envision a world where every woman participates with full dignity as an equal member of society. Center for Reproductive Rights 199 Water St., 22nd Floor New York, NY 10038 USA The Centre for Law and Policy Research is a not-for-profit trust that engages in law and policy research, supported by strategic litigation. It aims to reimagine and reshape public interest lawyering in India by seeking to advance core constitutional and human rights values. Its main areas of work are the protection of rights of women and girls, transgender persons, people with disabilities and the most marginalised among others. Centre for Law & Policy Research D6, Dona Cynthia Apartments 35 Primrose Road