The Journal of Effective Teaching an Online Journal Devoted to Teaching Excellence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Professional Wrestling, Sports Entertainment and the Liminal Experience in American Culture

PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING, SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT AND THE LIMINAL EXPERIENCE IN AMERICAN CULTURE By AARON D, FEIGENBAUM A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2000 Copyright 2000 by Aaron D. Feigenbaum ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are many people who have helped me along the way, and I would like to express my appreciation to all of them. I would like to begin by thanking the members of my committee - Dr. Heather Gibson, Dr. Amitava Kumar, Dr. Norman Market, and Dr. Anthony Oliver-Smith - for all their help. I especially would like to thank my Chair, Dr. John Moore, for encouraging me to pursue my chosen field of study, guiding me in the right direction, and providing invaluable advice and encouragement. Others at the University of Florida who helped me in a variety of ways include Heather Hall, Jocelyn Shell, Jim Kunetz, and Farshid Safi. I would also like to thank Dr. Winnie Cooke and all my friends from the Teaching Center and Athletic Association for putting up with me the past few years. From the World Wrestling Federation, I would like to thank Vince McMahon, Jr., and Jim Byrne for taking the time to answer my questions and allowing me access to the World Wrestling Federation. A very special thanks goes out to Laura Bryson who provided so much help in many ways. I would like to thank Ed Garea and Paul MacArthur for answering my questions on both the history of professional wrestling and the current sports entertainment product. -

ED 194 419 EDRS PRICE Jessup, John E., Jr.: Coakley, Robert W. A

r r DOCUMENT RESUME ED 194 419 SO 012 941 - AUTHOR Jessup, John E., Jr.: Coakley, Robert W. TITLE A Guide to the Study and use of Military History. INSTITUTION Army Center of Military History, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 79 NOTE 497p.: Photographs on pages 331-336 were removed by ERIC due to poor reproducibility. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 ($6.50). EDRS PRICE MF02/PC20 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *History: military Personnel: *Military Science: *Military Training: Study Guides ABSTRACT This study guide On military history is intended for use with the young officer just entering upon a military career. There are four major sections to the guide. Part one discusses the scope and value of military history, presents a perspective on military history; and examines essentials of a study program. The study of military history has both an educational and a utilitarian value. It allows soldiers to look upon war as a whole and relate its activities to the periods of peace from which it rises and to which it returns. Military history also helps in developing a professional frame of mind and, in the leadership arena, it shows the great importance of character and integrity. In talking about a study program, the guide says that reading biographies of leading soldiers or statesmen is a good way to begin the study of military history. The best way to keep a study program current is to consult some of the many scholarly historical periodicals such as the "American Historical Review" or the "Journal of Modern History." Part two, which comprises almost half the guide, contains a bibliographical essay on military history, including great military historians and philosophers, world military history, and U.S. -

PORT-AU-PRINCE and MONTREAL, 1934-1986 by Grace Louise Sanders a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requiremen

LA VOIX DES FEMMES: HAITIAN WOMEN’S RIGHTS, NATIONAL POLITICS AND BLACK ACTIVISM IN PORT-AU-PRINCE AND MONTREAL, 1934-1986 by Grace Louise Sanders A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History and Women’s Studies) in the University of Michigan 2013 Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Sueann Caulfield, Chair Associate Professor Jesse E. Hoffnung-Garskof Professor Tiya A. Miles Associate Professor Nadine C. Naber Professor Matthew J. Smith, University of the West Indies © Grace L. Sanders 2013 DEDICATION For LaRosa, Margaret, and Johnnie, the two librarians and the eternal student, who insisted that I honor the freedom to read and write. & For the women of Le Cercle. Nou se famn tout bon! ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the History and Women’s Studies Departments at the University of Michigan. I am especially grateful to my Dissertation Committee Members. Matthew J. Smith, thank you for your close reading of everything I send to you, from emails to dissertation chapters. You have continued to be selfless in your attention to detail and in your mentorship. Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof, thank you for sharing new and compelling ways to narrate and teach the histories of Latin America and North America. Tiya Miles, thank you for being a compassionate mentor and inspiring visionary. I have learned volumes from your example. Nadine Naber, thank you for kindly taking me by the hand during the most difficult times on this journey. You are an ally and a friend. Sueann Caulfield, you have patiently walked this graduate school road with me from beginning to end. -

Mecca of the Squared Circle Mecca of the Squared Circle

“His face is a crimson mask”—just one example Wrestling legends Ric Flair and Gordon Solie of a phrase coined by legendary wrestling play-by-play photo courtesy Gene Gordon czar Gordon Solie, a man who held a pivotal role in ©Scooter Lesley promoting the mass appeal of Florida wrestling. Watching Championship Wrestling from Florida was a staple of life for many Floridians. The fans were both overt and closeted, but they all knew the flashy moves and big finishes. CWF became a top-rated statewide soap opera for the unwashed masses from the early 1950s to the late ’80s. Stars such as Eddie & Mike Graham, The Great Malenko, Buddy Colt, Jack & Jerry Brisco, Dory & Terry Funk, and Kurt & Karl Von Brauner, accompanied by their manager “Gentleman” Saul Weingroff, comprised the main attraction for a circus made up of high flyers and strongmen, heels and baby faces—and we were the stunned audience. Cowboy Luttrall drove the shows’ success. In the 1940s, his challenge of Joe Lewis to a boxer vs. wrestler match became his claim to fame. Lewis won, but Cowboy made a name for himself. The rest is history. Luttrall had an eye for talent, he quickly recruited legends such as Eddie Graham and his “brother” Dr. Jerry Graham, Hans Schmidt, Buddy “Killer” Austin, Ray Villmer, and one of the most hated combos in the history of the game—Kurt & Karl Von Brauner, the German Twins. World War II was not far removed from the memories of those attending the shows at venues such as Tampa’s Fort Homer Hesterly Armory. -

Help, Mayor's Plea in Big Bond Quota

u BACK UP "TWrMVtTWII YOUR BOY l(Vrt—YOU LEND 2ND YOUI MONEY" WAR •' Buy an Additional LOAN V Band Today IvyMor* Snbepenknt - leaber Ww tot* Today XXXV. —No. 4 nrud us Koi-nml r\w» matter hKl Every Friday "I Mm lViat Office, WoiKlbrlrtge, N. .1. WOODBRIM.E, N. J., FRIDAY, APRIL 16. nt lR Qrntm St., Wnodbrldge, N. J. PRICE FIVE CENTS jpinie Low Scene From Seniors9 Mystery Play Ordinance •e, Rises Curbs DogAll Help, Mayor's Plea lv Nation Freedom In Big Bond Quota p,^rage I* Consider* .h No Animal To Be Per- Township Asked For ',|,ly Under That In^ mitted To Run With- They Give Their Lives _^. nmparablc Localities $510,000 In 3 Weeks; out Being Leashed Neiis 1st Subscrnta ''•'.'"'vnlii?--- Although juv* WOOUBRIDGE—Dog owners in You Can Lend Your Money WOODSRIDGE —Th« __ I ,ni, ni-.v, especially among e Township will have to pur- Uak of Telling 1510,000 in United ..", ,.,-in,,. II. general ram- iise tt'Hshos for their pets, if the To the readers of The Independent-Leader: Sutc<t War Bonds during- the n«t I, this country in' 19fS Hinance introduced on first read- throe weeks ait Woodbridg* Town- ,,,.,,. fewer offenses in g at a meeting cf ftfe lloiird of The lSybillion second war loan is the responsi- .«hip's part in the 11.1000,000,600 lk'i, iii (iroportion to pop I'alth is f'umHy adopted ;it the bility of nvery one of us. ."ipcond War,Loan campliign got ,n;,i, ,n most parts of the ssion May 10. -

Kit Young's Sale #137

Page 1 KIT YOUNG’S SALE #137 BAZOOKA BASEBALL Bazooka cards are among the toughest issues of the 1960’s. These full color cards were featured on boxes of Bazooka bubble gum. We recently picked up a nice grouping – most all cards are clean and really well cut. Many Hall of Famers and Hometown Heroes are offered here. Only one of each available. First time in a few years we’ve offered a big grouping. 1959 Bob Turley 1960 Yogi Berra Yankees 1961 Rocky Colavito Tigers 1963 Don Drysdale Dodgers 1966 Mickey Mantle Yankees 1964 Roberto Clemente Pirates 1965 Juan Marichal Giants Yankees VG 65.00 NR-MT 65.00 EX-MT 39.00 EX-MT 379.00 NR-MT 195.00 EX-MT 60.00 EX-MT 245.00 1959 BAZOOKA 1962 BAZOOKA 1964 BAZOOKA STAMPS Jim Davenport Giants .................................EX-MT $195.00 Mickey Mantle Yankees ...................... EX+/EX-MT $375.00 Juan Marichal Giants ....................................EX-MT $25.00 Roy McMillan Reds.......................................NR-MT 245.00 Johnny Romano Indians ...............................VG-EX 160.00 EX-MT @ $9.50 each: Hinton – Senators, O’Toole – Reds, Duke Snider Dodgers ...................................EX-MT 895.00 Dick Stuart Pirates ....................................VG/VG-EX 25.00 Rollins - Twins Bob Turley Yankees ......................................EX-MT 245.00 1963 BAZOOKA 1965 BAZOOKA 1960 BAZOOKA 2 Bob Rodgers Angels ............................ VG-EX/EX $10.00 2 Larry Jackson Cubs ...................................EX-MT $19.00 4 Hank Aaron Braves..................................NR-MT $195.00 4 Norm Siebern A’s .........................................EX-MT 15.00 3 Chuck Hinton Indians ..................................EX-MT 19.00 8 Yogi Berra Yankees ...........................................VG 65.00 8 Dick Farrell Colt .45s ................... -

Local Promotions in 1980

December 24, 1882 in Fremont, OH Opera Hall drawing ??? 1. Lucien Marc Christol beat Richard Dieterie in two straight falls. 2. Lucien Marc Christol beat beat Heinrich Webber in three falls. Janaury 15, 1887 in Sandusky, OH 1. Lucien Marc Christol beat Louis Schroeber in three straight falls. Janaury 18, 1887 in Sandusky, OH Turner Hall drawing ??? 1. Lucien Marc Christol beat Louis Schroeber in three falls of a “Graeco- Roman” match. Schroeder beat Christol. Christol beat Schroeder. Christol beat Schroeder. Janaury 24, 1887 in Sandusky, OH 1. World Lightweight Champ James Faulkner beat Lucien Marc Christol (20:35) in five falls. Christol beat Faulkner (7:45) in a “Graeco-Roman” fall. Faulkner beat Christol (11:35) in a “catch-as-catch-can” fall. Christol beat Faulkner (15:35) in a “Graeco-Roman” fall. Faulkner beat Christol (17:35) in a “catch-as-catch-can” fall. Faulkner beat Christol (20:35) in a “catch-as- catch-can” fall. February 5, 1887 in Sandusky, OH Fisher’s Hall drawing ??? 1. James Faulkner drew Lucien Marc Christol in five falls. Duncan C. Ross was the referee. Faulkner won the first two falls, one Graeco-Roman style and one catch-as-catch-can style. Christol then won a fall of each style. Faulkner comitted a foul in the last fall Graeco-Roman style so the match was declared a draw. February 8, 1887 in Sandusky, OH 1. George Miller beat Louis Schroeder in four falls of a “Graeco-Roman” match. Schroeder beat Miller. Miller beat Schroeder. Miller beat Schroeder. Miller beat Schroeder. February 28, 1887 in Sandusky, OH Fisher’s Hall drawing 300 1. -

The Relationship Between Wrestling, Television and American Culture

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2001 The Squared Circle and that Household Box: The Relationship between Wrestling, Television and American Culture Brian Stewart College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Stewart, Brian, "The Squared Circle and that Household Box: The Relationship between Wrestling, Television and American Culture" (2001). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626288. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ac4d-fy14 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Squared Circle and That Household Box: The Relationship Between Wrestling, Television and American Culture A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Brian Stewart 2001 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, May 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT I. HOW I GOT INTO THIS MESS AND THE MESS ITSELF: AN INTODUCTION II. TRADITIONAL WRESTLING: THE WAY THINGS WERE III. CONTEMPORARY WRESTLING: THE LENGTHS TO WHICH SOME PEOPLE WILL GO TO ESCAPE A CAGE IV. THE PHONE, THE MAT AND THE TV; OR THE REASON FOR THE CHANGE V. -

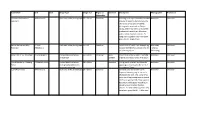

Name/Title ID # Date Image Type Image Size Region Or Nationality

Name/Title ID # Date Image Type Image Size Region or Gimmick Description Photographer Promotion Nationality [Unidentified masked A Montreal 9 Black and white photograph 25 x 20 cm Canadian Standing pose by an identified masked Unknown Unknown wrestler] wrestler dressed in his ring costume. This is one of 15 early wrestling photographs acquired on Ebay in spring 2008. They seem to document professional wrestling in Montreal and/or other Quebec centres. To keep them together they have been given the ID - A Montreal Pat Patterson and Billy A Funk- Black and white photograph 25 x 20 Canadian Action shot of Terry Funk attempting Machalek, Unknown Robinson Patterson 1 to slam Pat Patterson’s head onto the Terrance outside ring apron. (Winnipeg) Dory Funk Jr. vs. The Sheik A Funk-Sheik 1 Printed black and white 25 x 20 cm American Arab, Action shot of Dory Funk Jr. and the Unknown Unknown photograph Cowboy original Sheik beyond the ring apron. Hiro Matsuda vs. Amazing A Matsuda-Zuma Printed black and white 28 x 21 cm Japanese In ring action shot of Hiro Matsuda Unknown Unknown Zuma 1 photograph published in applying a nerve hold to the neck of wrestling magazine the Amazing Zuma. [Larry Raymond] A Montreal 1 Black and white photograph 25 x 20 cm Canadian Standing pose by wrestler Larry Unknown Unknown Raymond wearing ring attire and a championship belt. This is one of 15 early wrestling photographs acquired on Ebay in spring 2008. They seem to document professional wrestling in Montreal and/or other Quebec centres. To keep them together they have been given the ID - A Montreal [Ring Action Shot] A Montreal 10 Black and white photograph 20 x 25 cm Canadian Action shot of two wrestlers battling Unknown Unknown in a ring corner with a referee attempting to break up eye gouch by the bearded heel. -

Back Issues of Wrestling Revue

WWW.WRESTLEPRINTS.COM 2009 CLASSIC WRESTLING CATALOG PAGE 2 104473 Al Costello works over opponent on ropes Welcome to Wrestleprints! This catalog contains our current inventory of classic wrestling images from the Wres- 100796 AL Kashey - sitting publicity pose tling Revue Archives library of over 30,000 photos. If you would like more information about any of the items in 100812 Al Mercier classic wrestler posed 103708 Alaskan Jay York gives the big elbow to opponent this catalog, please visit our website, where you can view the image by item number or description, or please email 102538 Alaskan Mike York awaits bell in ring us ([email protected]) to answer any questions you may have. Note that many of these classic photos are in 100809 Alex Karras - wrestling photo of ex-football star black and white; again, to view, visit our website. Additionally, we are constantly updating our catalog, so the best 103174 Alexis Smirnoff - pose dphoto of west coast heel 103175 Alexis Smirnoff battles Lonnie Mayne way to keep up to date is to visit our website. 104742 Alexis Smirnoff color posed photo PHOTOS are printed on premium glossy paper, and are available in two sizes. 4”x6” photos are $9.95 each; 104001A Ali Bey the Turk - color posed photo 8”x10” photos are $19.95. To order, use the form on the back page of this catalog, or visit us online. 102217 All time great Killer Kowalski w/belt 100814 Amazing Zuma posed photo of classic wrestler VISIT WWW.WRESTLEPRINTS.COM 100826 Andre Drap beefcake pose of musclebound matman 100829 Andre Drap -

Neil Richards Pro-Wrestling Collection. – 4 M of Publications; Collector Cards: and Posters

Neil Richards Pro-Wrestling Collection. – 4 m of publications; collector cards: and posters. – 1900-2010 (inclusive) 1950-1980 (predominant). Born and educated in Ontario, but living in Saskatoon since 1971, Neil Richards (1949 - ) is a collector with a wide range of interests in popular culture. As a boy and youth he was a television fan of professional wrestling. He began to collect historical wrestling material in earnest in the 1990s. Much of the collection was acquired through purchases on EBay and from internet vendors. He has previously donated a large collection of early Regina wrestling programs (Regina Wrestling News – Shortt GV 1198.15 .R44) to the Special Collections Department of the University Library. Subsequently the great bulk of his collection was donated to the University of Saskatchewan Archives in 2010. The collection served as the primary source for the October 2009 exhibition , "Ring-A-Ding- Dong-Dandy: Glimpses of Wrestling History" held at the University of Saskatchewan Library. The collection has two principal focuses - the period 1950 to 1970, often seen as a golden age of professional wrestling due to the entertainment’s enormous popularity on early television, and material documenting wrestling in Canada, especially in Saskatchewan and other parts of Western Canada. The majority of the collection’s items are American in origin although many of these were distributed and widely available in Canada. Canadian produced photos and publications are additionally well represented. A small number of items were produced in Great Britain and Australia. The collection’s focus represents the collector’s personal interests – and the types of professional wrestling with which he had a personal connection or knowledge. -

February 26, 1971)

MUShare The Carbon Campus Newspaper Collection 2-26-1971 The Carbon (February 26, 1971) Marian University - Indianapolis Follow this and additional works at: https://mushare.marian.edu/crbn Recommended Citation Marian University - Indianapolis, "The Carbon (February 26, 1971)" (1971). The Carbon. 375. https://mushare.marian.edu/crbn/375 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Campus Newspaper Collection at MUShare. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Carbon by an authorized administrator of MUShare. For more information, please contact [email protected]. W~LT'S WRESTLING WORLD I have noticed in the past few weeks that there is an increasing interest in the sport of Professional Wrestling. I am rather impressed with this interest and I would like to tell all interested persons in Marian College and in the surrounding vicinities that Indianapolis is one of the largest professional wtestlingcapitals in the entire · world and has been the scene of may championship matches. Whenever a card is coming up that is scheduled wither at the Coliseum or at Tyndall Armo ~y, I will enter it into the Carbon as well as the results. rlere are the results of the last card at the Coliseum on February 13, 1971 which was almost my last match I would ever see aga;n: Kenny Dillinger defeated Fernandos Stampos Paul Christy defeated Freddy Rogers Angelo Poffo defeated Ivan Kalmikoff Erni_e "the Cat" Ladd pu 1ver i zed Poff o in a 1ater bout Bobo Brazil and Hans Schmidt battled to a draw Igor Vodik and Count Baron von Raschke each shared a fall until Igor was disqualified in the third fall when he and Ivan Kalmikoff, h~s manager, clobbered the Count which enabled Raschke to retain the title of "World Heavyweight Wrestling Champion".