Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thursday, April 6, 2017

BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING Thursday, April 6, 2017 5:30 PM Board of Supervisors’ Chambers County Government Center 70 West Hedding Street San Jose, CA 95110 AGENDA To help you better understand, follow, and participate in the meeting, the following information is provided: . Persons wishing to address the Board of Directors on any item on the agenda or not on the agenda are requested to complete a blue card located at the public information table and hand it to the Board Secretary staff prior to the meeting or before the item is heard. Speakers will be called to address the Board when their agenda item(s) arise during the meeting and are asked to limit their comments to 2 minutes. The amount of time allocated to speakers may vary at the Chairperson's discretion depending on the number of speakers and length of the agenda. If presenting handout materials, please provide 25 copies to the Board Secretary for distribution to the Board of Directors. The Consent Agenda items may be voted on in one motion at the beginning of the meeting. The Board may also move regular agenda items on the consent agenda during Orders of the Day. If you wish to discuss any of these items, please request the item be removed from the Consent Agenda by notifying the Board Secretary staff or completing a blue card at the public information table prior to the meeting or prior to the Consent Agenda being heard. AGENDA BOARD OF DIRECTORS Thursday, April 06, 2017 . Disclosure of Campaign Contributions to Board Members (Government Code Section 84308) In accordance with Government Code Section 84308, no VTA Board Member shall accept, solicit, or direct a contribution of more than $250 from any party, or his or her agent, or from any participant, or his or her agent, while a proceeding involving a license, permit, or other entitlement for use is pending before the agency. -

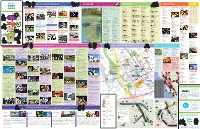

2018 Event Calendar City of San Jose Office of Cultural Affairs (Note: Listing on Calendar Does Not Guarantee Event Approval)

2018 Event Calendar City of San Jose Office of Cultural Affairs (Note: Listing on Calendar does not guarantee event approval) Event Date/ Event Name Organization Organizer OCA Est Time Location URL Contact Info Contact Attend July 2018 Jul 1 It’s Happening/Spring Summer in Plaza City of San Jose TT de Cesar Chavez Park Jul 4 Rotary Fireworks Show 2018 Rotary Club of San Jose Matt Micheletti MI 75000 6 PM-11 PM Discovery Meadow 408.623.9090 West San Carlos, Almaden Blvd, 87 off ramp, Woz Way & Delmas Avenue [email protected] Jul 4 CD 10 July 4th Family Fun Festival & City of San Jose Office of Councilmember Denelle Fedor MI 20000 Fireworks Show 2018 Johnny Khamis (CD10) 2 PM-11 PM www.sanjoseca.gov 408.535.4910 Almaden Lake Park [email protected] Winfield from Coleman to Quarry Rd Jul 4 Rose White and Blue Parade Alameda Business Association Bryan Franzen NR 40000 10 AM-3 PM www.the-alameda.com 408-771-9853 Dana Avenue, University Avenue, The Alameda, Shasta Avenue [email protected] Jul 4-4 July 4th Parade and 5K Run Montevideo Improvement Association Ron Blumstein NR 768 Wed: 8:30 AM-9:30 PM Coleman Road, Meridian Avenue, Redmond Ave, Montelegre Drive 408-891-2431 Wed: 11 AM-12 PM [email protected] May 4 thru Nov 16 Downtown Farmers Market San Jose Downtown Association Amy Anderson NR 28345 Fridays 10:00 AM to www.sjdowntown.org 408-279-1775 x 324 2:00 PM San Pedro Street between Santa Clara and Saint John [email protected] Jul 6-8 St. -

Public Art San Jose in Storefront Windows

21 20 Opportunities to see art abound throughout the downtown. In the SoFA district (1st Street south of San Carlos Street), in addition to the numerous galleries, several of the businesses also show art regularly, as well as the on-going series of changing artwork Public Art San Jose in storefront windows. City Hall hosts a regularly changing exhibit program in its 4th Street City Windows Gallery, the City Hall 1st floor 12 6 Wing hallway, display cases on the first floor of the tower building, and on the 18th floor of the tower. San Jose State University has an ongoing exhibit program at Thompson Gallery and the 2nd floor Downtown Nightscape to Downtown San José, Silicon Valley’s of the MLK Library. And temporary projects regularly appear in In the evening, downtown becomes a Welcome downtown City Center where the arts and entertainment, business and living conjunction with festivals and events. dynamic lightscape— SoFA district, 1st blend together in an innovative way. The San José Public Art and 2nd Streets, and along Santa Clara Several resources will help visitors and residents alike discover art Program is celebrating its 25th anniversary—a milestone of artistic and San Fernando Streets. Artists, and art events throughout downtown: recognizing this unique energy, have exploration and community enrichment in the downtown and * www.artsopolis.com created works that enhance the skyline beyond. From the Martin Luther King, Jr. Joint Library and City Hall, * www.southfirstfridays.com and the streetscape. Dynamic light to integration with private development, to the Guadalupe River * www.sjdowntown.com works include Jim Conti’s interactive Park, and even temporary projects, artists work to find unique ways * www.sanjose.org Show Your Stripes (25), Ben Rubin’s to heighten the experience of the ever changing downtown. -

South FIRST FRIDAYS Brochure

an eclectic evening of arts and entertainment in downtown San Jose’s SoFA District South FIRST FRIDAYS Art Walk San Jose’s SoFA District has all the earmarks of an area full of potential. It has a history of independent retailers, cafés, restaurants, nightclubs and creative offices. And now, seven galleries in the three blocks from San Carlos to Reed streets. Each venue has a unique personality and place of importance in San Jose's art and cultural scene; together we hope to expand the art going public's experience by providing a casual, easy access flow between all the venues. The South FIRST FRIDAYS Art Walk is the perfect opportunity to come out, meet old friends and new, and be inspired by the wide variety of art exhibits and special events. 8pm ’til late - free & open to the public for full listings of current exhibits and events visit: www.SouthFirstFridays.com or call: 408-271-5155 ANNO DOMIN I// the second coming of Art & Design 366 South First St. Anno Domini has been representing and promoting urban contemporary art and culture e since we opened our doors in July 2000. What began as a monthly get-together in a r u t warehouse space where new, emerging and often ignored art forms could flourish and l be celebrated, A.D. has come to be recognized nationally and abroad for its vision in u c this genre. Each First Friday of the month we unveil a new exhibit with an artist reception. & t The exhibitions range from regional to international street artists, tattoo art, lowrider r bikes, skater/surfer culture, indie publishing, DIY fashion and sound art. -

VTA Daily News Coverage for Monday, May 13, 2019 1

From: VTA Board Secretary <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, May 13, 2019 2:09 PM To: VTA Board of Directors <[email protected]> Subject: From VTA: May 13, 2019 Media Clips VTA Daily News Coverage for Monday, May 13, 2019 1. Express lane expansion on way (The Daily Journal) 2. Caltrain explores SF, San Mateo, Santa Clara sales tax to fund electrification (San Francisco Examiner) 3. Caltrain derails in San Jose, widespread delays reported in both directions (San Francisco Chronicle) 4. Mud, weeds will be dealt with on South Bay’s most popular bike trail: Roadshow (Mercury Nerws) 5. North San Jose: City could green-light more housing (Mercury News) 6. Staedler: Could the Sharks leave San Jose? (San Jose Spotlight) Express lane expansion on way (The Daily Journal) Next leg to be established spans from San Francisco International Airport to San Francisco The express lanes project in San Mateo County that broke ground in March was always meant to be just one segment of a continuous stretch of express lanes between San Francisco and San Jose. By 2022, express lanes will be constructed on Highway 101 between Whipple Avenue and Interstate 380 and, if everything goes according to plan, those express lanes will extend north to Fourth and King streets in San Francisco by 2026. Express lanes already exist in Santa Clara County and will eventually connect to the ones being built in San Mateo County. Express lanes promise speeds of at least 45 mph at all times by charging solo drivers to use them while buses and carpools of three people or more will be able to travel on them for free. -

2664 Berryessa Road

OFFERING MEMORANDUM CLICK HERE FOR PROPERTY VIDEO BERRYESSA PROFESSIONAL CENTER 2664 BERRYESSA ROAD | SAN JOSE | CALIFORNIA CONFIDENTIALITY & DISCLAIMER The information contained in the following Marketing Brochure is proprietary and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it from Marcus & Millichap and should not be made available to any other person or entity without the written consent of Marcus & Millichap. This Marketing Brochure has been prepared to provide summary, unverified information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. Marcus & Millichap has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation, with respect to the income or expenses for the subject property, the future projected financial performance of the property, the size and square footage of the property and improvements, the presence or absence of contaminating substances, PCB's or asbestos, the compliance with State and Federal regulations, the physical condition of the improvements thereon, or the financial condition or business prospects of any tenant, or any tenant's plans or intentions to continue its occupancy of the subject property. The information contained in this Marketing Brochure has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable; however, Marcus & Millichap has not verified, and will not verify, any of the information contained herein, nor has Marcus & Millichap conducted any investigation regarding these matters and makes no warranty or representation whatsoever regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information provided. All potential buyers must take appropriate measures to verify all of the information set forth herein. -

Getting Around Downtown and the Bay Area San Jose

Visit sanjose.org for the Taste wines from mountain terrains and cooled by ocean Here is a partial list of accommodations. Downtown is a haven for the SAN JOSE EVENTS BY THE SEASONS latest event information REGIONAL WINES breezes in one of California’s oldest wine regions WHERE TO STAY For a full list, please visit sanjose.org DOWNTOWN DINING hungry with 250+ restaurants WEATHER San Jose enjoys on average Santa Clara County Fair Antique Auto Show There are over 200 vintners that make up the Santa Cruz Mountain wine AIRPORT AREA - NORTH Holiday Inn San Jose Airport Four Points by Sheraton SOUTH SAN JOSE American/Californian M Asian Fusion Restaurant Gordon Biersch Brewery 300 days of sunshine. LEAGUE SPORTS YEAR ROUND MAY July/August – thefair.org Largest show on the West coast appellation with roots that date back to the 1800s. The region spans from 1350 N. First St. San Jose Downtown 98 S. 2nd Street Restaurant Best Western Plus Clarion Inn Silicon Valley Billy Berk’s historysanjose.org Mt. Madonna in the south to Half Moon Bay in the north. The mountain San Jose, CA 95112 211 S. First St. (408) 418-2230 – $$ 33 E. San Fernando St. Our average high is 72.6˚ F; San Jose Sabercats (Arena Football) Downtown Farmer’s Market Summer Kraftbrew Beer Fest 2118 The Alameda 3200 Monterey Rd. 99 S. 1st St. Japantown Farmer’s Market terrain, marine influences and varied micro-climates create the finest (408) 453-6200 San Jose, CA 95113 (408) 294-6785 – $$ average low is 50.5˚ F. -

Sofa's “Outdoor Living Room” for San Jose's Emerging Arts and Culture

SoFA’s “Outdoor Living Room” for San Jose’s Emerging Arts and Culture District Name of organization: 1stACT Silicon Valley Website: www.1stact.org Name of contact person: Connie Martinez, Managing Director and CEO Address: 38 W. Santa Clara Street, San Jose, CA 95113 Email: [email protected] Phone: 408-200-2020 Address of the proposed work: Parque De Los Pobladores - Gore Park, South First Street between William and Reed What is the mission of this organization? With place making and community building as its driving goals, 1stACT Silicon Valley’s mission is to inspire leadership, participation and investment at the intersection of art, creativity and technology. Provide a brief history of the organization. In 2003, a small group of volunteer civic leaders began a conversation about the way Silicon Valley looks, feels and invests in its community. By 2007, a growing network of cross-sector leaders was engaged in the conversation and 1stACT Silicon Valley was officially established to help create a stronger sense of place in one of the most broadly diverse, culturally transformative, and economically significant regions of the world. With urban design and arts and culture as strategies for building community and increasing attachment to “this place,” 1stACT began catalyzing change—a formidable challenge fueled by large immigrant populations connected to some place else, a suburban development pattern that divides the region, and an entrepreneurial culture that thrives on constant churn. 1stACT’s urban design agenda focused on downtown San Jose because of its unrealized potential as Silicon Valley’s urban core and its relevance to Silicon Valley’s future. -

Santa Clara-San Jose City Guide

San Jose, California San Jose, California Overview Introduction San Jose, California, is more than just the unofficial capital of Silicon Valley, the place where the U.S. computer industry took off and created a high-technology world. Palm trees and luxury hotels line busy boulevards in lively downtown San Jose, and the city's trendy restaurants, classy shops and lively nightspots attract both visitors and locals, including many who work in the world of technology. Despite its sudden growth during the tech boom of the 1990s, San Jose retains its small-town charm. Highlights Sights—The strange and beautiful Winchester Mystery House; the historic Peralta Adobe and Fallon House; the Montalvo Arts Center. Museums—The amazing interactive exhibits at The Tech Museum of Innovation; masterworks at the San Jose Museum of Art; the large collection of Egyptian artifacts at the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum & Planetarium. Memorable Meals—The enchanting ambience and French fare at La Foret Creekside Dining; the funky atmosphere of Henry's Hi-Life. Late Night—Drinking and dancing at San Jose Bar and Grill; live music at JJ's Lounge. Walks—A hike in nearby Alum Rock Park; Santa Cruz Mountains in Portola Redwoods State Park; a stroll along the boardwalk at Santa Cruz Beach; a rose-scented walk through Guadalupe River Park & Gardens; a hike in the hillside trails around the Montalvo Arts Center. Especially for Kids—The Children's Discovery Museum of San Jose; Happy Hollow Park and Zoo. Geography San Jose is in the Santa Clara Valley, otherwise known as Silicon Valley. It is bordered by two mountain ranges, the Santa Cruz Mountains to the west and the Diablo Range to the east. -

9.28.15 Public Art Committee Meeting Materials

City of Florence Public Art Committee Florence City Hall 250 Hwy 101 Florence, OR 97439 541-997-3437 www.ci.florence.or.us September 14, 2015 10:00 a.m. AGENDA Members: Harlen Springer, Chairperson Susan Tive, Vice-Chairperson SK Lindsey, Member Jo Beaudreau, Member Ron Hildenbrand, Member Jennifer French, Member Jayne Smoley, Member Joshua Greene, Council Ex-Officio Member Kelli Weese, Staff Ex-Officio Member With 48 hour prior notice, an interpreter and/or TDY: 541-997-3437, can be provided for the hearing impaired. Meeting is wheelchair accessible. CALL TO ORDER – ROLL CALL 10:00 a.m. 1. APPROVAL OF AGENDA 2. PUBLIC COMMENTS This is an opportunity for members of the audience to bring to the Public Art Committee’s attention any item not otherwise listed on the Agenda. Comments will be limited to a maximum time of 15 minutes for all items. 3. NEW OR ONGOING PROJECTS • Discussion of interim policy to handle new or ongoing projects within long term Approx. work plan 10:05 a.m 4. SHORT REPORTS ON COMMUNITY PROJECTS Approx. • • Potential Totem Pole Art Piece Dancing with Sea Lions Project 10:15 a.m. • Downtown Revitalization Team • Florence Urban Renewal Agency 5. PUBLIC ART PLAN AND POLICY • Discussion of best ways to proceed with the following tasks, including assigning tasks to particular members and/or establishing sub-teams Example Art Plan & Policy Review: Discussion of important elements to o be incorporated into the City of Florence Public Art Plan & Policy Approx. 10:25 a.m. o Community Outreach: Discussion of potential community outreach practices to gather input including surveys and/or stakeholder meetings / interviews o Goals and Guiding Principles o Locations: Potential ideal locations for visual public art in the community 6. -

±6,969 Square Feet 431 S

N. 1st St. FOR SALE > THE COROTTO BUILDING IN THE SoFA DISTRICT, DOWNTOWN SAN JOSE ±6,969 Square Feet 431 S. 1ST STREET, SAN JOSE, CA Hedding St. Available for the first time in decades, the Corotto Building is located in the heart of San Taylor St. Jose’s eclectic SoFA District, the visual arts and entertainment district of the Downtown. Built in the early 1900’s, the Corotto Building presents a unique opportunityN.Tenth St. to own a piece of San Jose’s past, while being in positioned in the St. ian path of its future.Jul Santa Clara St. nando San Fer S. 4th St. San Jose M S. 3rd St. State a S. 2nd St. r k S.1st St. Univ. e Almaden Blvd.t S t . lvador St. Sa . San s lo William St St. Car ed 87 San SITE Re 280 N COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL 450 West Santa Clara Street TOM NELSON San Jose, CA 95113 +1 408 282 3960 +1 408 282 3800 Main [email protected] +1 408 292 8100 Fax CA License No. 01451516 www.colliers.com 431 S. 1ST STREET, SAN JOSE, CA FOR SALE The Corotto Building Area Highlights Building Highlights > A ground zero location in the South First Area, adjacent to the new > Size: ±6,969 square feet on ±7,004 square foot parcel. Uproar Brewing Company and The Ritz night club, as well as many other > High ceiling with a barrel roof system with open trusses and skylights. restaurants and entertainment venues. > Two Building Addresses > In the path of growth with many newly built or planned residential developments within a 2-minute walk. -

Downtown San Jose Real Estate Tour 2016

DOWNTOWN SAN JOSE REAL ESTATE TOUR 2016 SPEAKING NOTES Welcome to the DT Tour… as you may have noticed in our marketing efforts for this event, San Jose was listed by Dell as the most future-ready city in the country. They used three primary characteristics to identify future ready cities: 1. The ability to attract people who are engaged in and open to lifelong learning that drives innovation; 2. Businesses that thrive in collaborative environments; 3. Infrastructure that provides platforms for people to engage, collaborate, learn and innovate. Facts: San Jose State is the 6 th highest rated public university on the west coast and the Davidson Engineering School is the 3 rd highest ranked public engineering program in the U.S according to U.S News and World Reports. • Current Population : Approximately 1,042,094 • Tech Companies Downtown: There are 120+ tech companies downtown! • Employment – The Silicon Valley added 32,000 jobs between July 2015 and July 2016. • Tech Companies added 3,300 jobs in May 2016 in Silicon Valley. • Gross Metro Product per Capita – San Jose’s GMP per capita is $105,482, more than double the national average according to an article published by Bloomberg in November 2015. • Metro Area Education Ranking – 3rd highest # of college educated graduates in the country, ranking behind Washington DC and Ann Arbor, MI in a survey done by Forbes Magazine dated July 26, 2016. • San Jose was ranked as the #1 best city in America to live and work in the U.S. in an article published by Business Insider on May 19, 2016.