Come Closer Acousmatic Intimacy in Popular Music Sound

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Gabriel's Secret World - 4 Worlds Limited Edition Mp3, Flac, Wma

Peter Gabriel Xplora 1: Peter Gabriel's Secret World - 4 Worlds Limited Edition mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock Album: Xplora 1: Peter Gabriel's Secret World - 4 Worlds Limited Edition Country: UK & Europe Released: 1994 Style: Pop Rock, Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1565 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1146 mb WMA version RAR size: 1958 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 716 Other Formats: TTA VOX MP3 VQF ADX MPC APE Tracklist Hide Credits Secret World Live (CD) CD1-1 Come Talk To Me 6:13 CD1-2 Steam 7:45 Across The River CD1-3 6:00 Written-By – David Rhodes, Shankar, Stewart Copeland CD1-4 Slow Marimbas 1:41 Shaking The Tree CD1-5 9:18 Written-By – Youssou N'Dour CD1-6 Red Rain 6:15 CD1-7 Blood Of Eden 6:58 CD1-8 Kiss That Frog 5:58 CD1-9 Washing Of The Water 4:07 CD1-10 Solsbury Hill 4:42 CD2-1 Digging In The Dirt 7:36 CD2-2 Sledgehammer 4:58 CD2-3 Secret World 9:10 CD2-4 Don't Give Up 7:35 CD2-5 In Your Eyes 11:32 Secret World Live (VHS) VHS1 Come Talk To Me VHS2 Steam Across The River VHS3 Written-By – David Rhodes, Shankar, Stewart Copeland VHS4 Slow Marimbas Shaking The Tree VHS5 Written-By – Youssou N'Dour VHS6 Blood Of Eden VHS7 San Jacinto VHS8 Kiss That Frog VHS9 Washing Of The Water VHS10 Solsbury Hill VHS11 Digging In The Dirt VHS12 Sledgehammer VHS13 Secret World VHS14 Don't Give Up VHS15 In Your Eyes Companies, etc. -

Air : Esce Il 10 Giugno “Twentyears” Il Primo Best-Of Del Duo Francese La Super Delux Edition Limitata E Numerata Sara’ Disponibile Dal 22 Luglio

AIR : ESCE IL 10 GIUGNO “TWENTYEARS” IL PRIMO BEST-OF DEL DUO FRANCESE LA SUPER DELUX EDITION LIMITATA E NUMERATA SARA’ DISPONIBILE DAL 22 LUGLIO 20/04/2016 AIR ESCE IL 10 GIUGNO “TWENTYEARS” IL PRIMO BEST-OF DEL DUO FRANCESE LA SUPER DELUX EDITION LIMITATA E NUMERATA SARA’ DISPONIBILE DAL 22 LUGLIO DOPO UNA LUNGA ASSENZA DAL PALCOSCENICO DURATA SEI ANNI GLI AIR TORNANO LIVE IN ITALIA: VENERDÌ 20 MAGGIO IN CONCERTO AL LABIRINTO DELLA MASONE IN PROVINCIA DI PARMA SABATO 21 MAGGIO HEADLINER A ROMA DEL FESTIVAL SPRING ATTITUDE Gli AIR, duo francese di musica elettronica vincitore di numerosi dischi di platino, pubblicheranno il 10 Giugno “Twentyears”, la loro prima antologia che celebra i vent’anni dal loro debutto internazionale. Disponibile in doppio CD, doppio LP e in versione digitale, il primo CD del Best-Of include grandi successi come “Sexy Boy”, “Playground Love”, "Kelly Watch the Stars", “Cherry Blossom Girl” e “Le soleil est près de moi”. Il secondo CD contiene 14 tracce rare e inedite tra cui “Crickets” e “The Way You Look Tonight” tratte dagli album Pocket Symphony e 10 000 Hz Legend, “Adis Abebah” dalla colonna sonora di Quartier lointain, “Roger Song” scritta per Corman’s World, “The Duelist” interpretata da Charlotte Gainsbourg e Jarvis Cocker durante la registrazione di the Pocket Symphony. La Super Deluxe Edition sarà disponibile dal 22 Luglio e conterrà un poster da collezione, il Best-Of in doppio CD, il doppio LP colorato e un terzo CD in cui gli AIR hanno remixato brani di altri artisti come David Bowie, Beck, Depeche Mode e Neneh Cherry. -

Robert Badinter Confrontation Entre Ce Qu’Il a De Plus Stimulant

LI 181:Mise en page 1 05/05/2010 11:25 Page 1 A VOUS DE LIRE ! NUIT DES MUSÉES ORSAY NOUVELLE 3000 LIEUX 300 LYCÉENS INITIATIVE D’EXPOSITION DIALOGUENT CANNES, SHANGHAI 2010... EN FAVEUR OUVERTS EN AVEC ROBERT COMMENT DE LA LECTURE EUROPE BADINTER LA FRANCE « EXPORTE » SA CULTURE CULTURECOMMUNICATION LE MAGAZINE DU MINISTÈRE DE LA CULTURE ET DE LA COMMUNICATION / MAI 2010 N° 181 TAPIS ROUGE ET PHOTOGRAPHES : LES RITUELS DU FESTIVAL DE CANNES REPRENNENT À PARTIR DU 12 MAI. SUR NOTRE PHOTO : ISSN : 1255-6270 LE CINÉASTE WONG KAR WAI ET L’ÉQUIPE DE SON FILM EN 2007 (DÉTAIL) © AFP PHOTO / FRED DUFOUR / POOL LI 181:Mise en page 1 05/05/2010 11:25 Page 2 LE TEMPS FORT ACTUALITÉS Shanghai 2010 et Festival de Cannes Comment la France « exporte » sa culture PARTICIPATION À L’EXPOSITION UNIVERSELLE DE SHANGHAI, ORGANISATION DU FESTIVAL DE CANNES… ENMAI, LA CULTURE FRANÇAISE VA SE MOBILISER SUR LA SCÈNE INTERNATIONALE. NE ville meilleure pour une meilleure vie ». C’est sur ce thème – placé sous le signe du déve- loppement durable mais aussi du plaisir de vivre dans les villes – que l’Exposition universelle de « Shanghai a ouvert ses portes le 1er mai. Pendant six mois,U elle va présenter, via des pavillons nationaux, la diversité des principales richesses – entre innovations et traditions – de 192 pays, dont 31 pays africains et 50 organisations internationales, ce qui constitue un record inégalé de participants à une Exposition universelle. Autre chiffre considérable : celui du nombre de visi- teurs prévus. Pour l’édition 2010, pas moins de 70 à 100 millions © AFP PHOTO / FRED DUFOUR POOL © sont attendus jusqu’au 31 octobre, soit deux à trois fois plus que pour la précédente édition qui s’est tenue en 2005 au Japon. -

Multimédia En Questions À La Bibliothèque Nationale De France

:>• Ecole Nationale Sup6rieure des Sciences de 1'information et des biblioth6ques Diplome de conservateur de bibliotheque Memoire d'etude Le multimedia en questions a la Bibliotheque nationale de France: le depot legal d'un nouveau support Joelle Jezierski 1995 BIBLIOTHEQUE DE L ENSSIB Ecole Nationale Superieure des Sciences de Vinformation et des bibliotMques Dipldme de conservateur de bibliotheque Memoire d'etude Le multimedia en questions a la Bibliotheque nationale de France : le depot legal d'un nouveau support Joelle Jezicrski Stage effectue au Departement de la Phonotheque et de 1'Audiovisuel de la Bibliotheque nationale de France, sous la direction de Cecile Franc Resume Depuis la loi n° 92-546 du 20 juin 1992, les documents multimedias sont soumis, au meme titre que les videogrammes et que les phonogrammes, a 1'obligation de depot legal, dont est affectataire le departement de la Phonotheque et de 1'Audiovisuel de la Bibliotheque nationale de France. Ayant a faire face a un marche encore mal defini et peu structure, et a un secteur editorial tout juste naissant, le service du depot legal a defini une strategie efficace de prospection et de developpement de ces fonds, tout en participant aux recherches en cours sur leur traitement bibliographique et leur conservation. En outre, il a permis d'integrer ces documents au sein du systeme audiovisuel qui sera mis en place sur le site de Tolbiac, enrichissant ainsi ses activites en direction du public. Abstracts A new law about legal deposit in France was promulgated in 1992, which decided to extend the legal deposit to multimedia documents. -

Carlton Barrett

! 2/,!.$ 4$ + 6 02/3%2)%3 f $25-+)4 7 6!,5%$!4 x]Ó -* Ê " /",½-Ê--1 t 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE !UGUST , -Ê Ê," -/ 9 ,""6 - "*Ê/ Ê /-]Ê /Ê/ Ê-"1 -] Ê , Ê "1/Ê/ Ê - "Ê Ê ,1 i>ÌÕÀ} " Ê, 9½-#!2,4/."!22%44 / Ê-// -½,,/9$+.)"" 7 Ê /-½'),3(!2/.% - " ½-Ê0(),,)0h&)3(v&)3(%2 "Ê "1 /½-!$2)!.9/5.' *ÕÃ -ODERN$RUMMERCOM -9Ê 1 , - /Ê 6- 9Ê `ÊÕV ÊÀit Volume 36, Number 8 • Cover photo by Adrian Boot © Fifty-Six Hope Road Music, Ltd CONTENTS 30 CARLTON BARRETT 54 WILLIE STEWART The songs of Bob Marley and the Wailers spoke a passionate mes- He spent decades turning global audiences on to the sage of political and social justice in a world of grinding inequality. magic of Third World’s reggae rhythms. These days his But it took a powerful engine to deliver the message, to help peo- focus is decidedly more grassroots. But his passion is as ple to believe and find hope. That engine was the beat of the infectious as ever. drummer known to his many admirers as “Field Marshal.” 56 STEVE NISBETT 36 JAMAICAN DRUMMING He barely knew what to do with a reggae groove when he THE EVOLUTION OF A STYLE started his climb to the top of the pops with Steel Pulse. He must have been a fast learner, though, because it wouldn’t Jamaican drumming expert and 2012 MD Pro Panelist Gil be long before the man known as Grizzly would become one Sharone schools us on the history and techniques of the of British reggae’s most identifiable figures. -

Seeing Beyond the End of the World in Strange Days and Until the End of the World

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 7 Issue 1 April 2003 Article 6 April 2003 Seeing Beyond the End of the World in Strange Days and Until the End of the World S. Brent Plate Hamilton College - Clinton, [email protected] Tod Linafelt Georgetown University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Plate, S. Brent and Linafelt, Tod (2003) "Seeing Beyond the End of the World in Strange Days and Until the End of the World," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol7/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing Beyond the End of the World in Strange Days and Until the End of the World Abstract Herein we offer a critique of contemporary filmic visions of apocalypse. The problem with many Hollywood-style apocalyptic films is that they expect the end of the world to be a spectacular end of the whole world. Against this, by reviewing two contemporary films (Strange Days and Until the End of the World) we suggest that apocalypse may take on a greater significance if we understand that there are many worlds, and that rather than expecting the end of the world, we should be more vigilant in our examinations of the endings of a world. With this in mind, apocalyptic predictions given by Jesus in the gospels are reread and we note how these prophecies have already been fulfilled. -

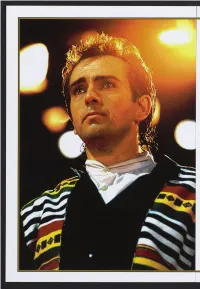

Peter Gabriel by W Ill Hermes

Peter Gabriel By W ill Hermes The multifaceted performer has spent nearly forty years as a solo artist and music innovator. THERE HAVE BEEN MANY PETER GABRIELS: THE PROG rocker who steered the cosmos-minded genre toward Earth; the sem i- new waver more focused on empathic storytelling and musical inno vation than fashion or attitude; the Top Forty hitmaker ambivalent about the spotlight; the global activist whose Real World label and collaborations introduced pivotal non-Western acts to new audiences; the elder statesman inspiring a new generation of singer-songwrit ers. ^ So his second induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, as a solo act this time - his first, in 2010, was as cofounder of the prog-pop juggernaut Genesis - seems wholly earned. Yet it surprised him, especially since he was a no-show that first time: The ceremony took place two days before the notorious perfectionist began a major tour. “I would’ve gone last time if I had not been about to perform,” Gabriel (b. February 13,1950) explained. “I just thought, 1 can’t go. We’d given ourselves very little rehearsal time.’” ^ “It’s a huge honor,” he said of his inclusions, noting that among numerous Grammys and other awards, this one is distinguished ‘because it’s more for your body of work than a specific project.” ^ That body of work began with Genesis, named after the young British band declined the moniker of “Gabriel’s Angels.” They produced their first single (“The Silent Sun”) in the winter of 1968, when Gabriel was 17. -

LE MONDE/PAGES<UNE>

www.lemonde.fr 57e ANNÉE – Nº 17530 – 7,50 F - 1,14 EURO FRANCE MÉTROPOLITAINE -- MARDI 5 JUIN 2001 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI Yasser Arafat Les emplois-jeunes seront prolongés isolé et affaibli b Le gouvernement veut pérenniser ce dispositif né en 1997 qui emploie aujourd’hui 276 950 jeunes a Le président b Ces mesures iront jusqu’en 2008, principalement dans la fonction publique b L’éducation et la police de l’Autorité auront la priorité b Les employeurs associatifs bénéficieront d’une « rallonge » financière plus limitée palestinienne LA MINISTRE de l’emploi et de de ces « nouveaux services ». Les la solidarité, Elisabeth Guigou, pré- mesures de « consolidation » des est sommé de mettre sentera, mercredi 6 juin, le plan de emplois-jeunes s’étendront jusqu’en pérennisation des emplois-jeunes. 2008 dans la fonction publique prin- un terme à l’Intifada Cette annonce pourrait être faite cipalement, où les contrats à durée en présence des ministres de l’édu- déterminée de cinq ans, de droit pri- CLAUDE PARIS/AP cation nationale, de l’intérieur, de vé, subsisteront. Mais, pour une par- a Critiqué dans l’environnement, du sport ou du tie des associations, le coup de pou- TRANSPORTS tourisme, dont les secteurs sont ce supplémentaire ne s’étalera que son camp, il est sous très concernés par l’avenir de ce sur trois ans – jusqu’en 2005 – et programme, né en 1997. La plupart sera très sélectif. Les embauches res- TGV, des 276 950 emplois-jeunes vont teront donc ouvertes, notamment la pression d’Israël, être prolongés. -

News Mars2010

Bulletin Culturel March 2010 focus AIR - PHOENIX THEATRE ÉRIC HAZAN UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO charlie winston CANADIAN MUSIC WEEK In « L’Image-Malice » culinary preparations sinous descriptions are used to make us experiment scale audacious comparisons : “…from its end of the XIX th Contents century attested presence in French the word bretzel comes from derived latin “arm” brachium, brachita to common latin brachitella . By form analogy this PAGE 3 - Festival goes to name a salted and cumin peppered 8- or arms- shaped light pastry . If PAGE 7 - Music you move it the other way around, the bretzel draws something which can be related to the symbol of infinite.” * For the compared symbolic appearance of PAGE 8 - Cinema the strudel may I wish you to open the book ? PAGE 8 - Theatre To which infinite or to which crunchy cookies, do the March Francophonie cel- PAGE 9 - Dance ebrations invite us to enjoy in 2010? Thanks to its Alliance Française and part- ners, Winnipeg highlights Africa with musical performances, tales and films. In PAGE 10 - TV Toronto, there are many good wills around Francophonie including Alliance PAGE 11 - Speaking française and many more. Francophone Film Festival “Cinefranco” get started early March for the kids and overlapps end of March with April for parents and PAGE 13 - Release friends. * « DevantJoël le Savary, Temps /Attaché L’Image-Malice Culturel » Georges Didi-Huberman , Les Editions de Minuit, 2000, Paris, p. 155 . March 2010 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 1234567 MSF AT THE MUNK PERSÉPOLIS -

Un Libro Para Ti

El grupo australiano Jumping Fences (Saltando Cercas), se pre- senta hoy en la peña 3Tasas, del trovador Silvio Alejandro, en el CULTURA Pabellón Cuba y el sábado 30, en la sala White, en Matanzas. 7 JUNIO 2018 VIERNES 29 Lecturas de verano: un libro para ti G CINES ricardo alonso venereo j, Vedado, la dirección provincial de Cul- sistema de ediciones Extramuros, entre Esta semana los cines Yara, Charles Chaplin, tura ha organizado el siguiente progra- los que se encuentran los títulos, Para la sala 31 y 12, la Glauber Rocha, la sala 1 del Nada mejor para pasar el verano que la ma: 10:00 a.m., presentación del grupo leer con una sola mano, Pensar el Barrio Multicine Infanta y el Centro cultural Engua- lectura de un buen libro. Por eso como de danza Imagen, de la Casa de Cultura Chino, La pícara piedra y No despierten yabera estarán estrenando la cinta Somnia. parte de las actividades del Verano 2018, de Arroyo Naranjo, y Cesé Coralillo; a las mariposas. Desde las 6:00 p.m., se Dentro de tus sueños (Mike Flanagan, 2016). que tendrá como lema A disfrutar Cuba, el 12:30 p.m. Espacio Tatuado. Lectura podrá disfrutar de la Banda de concierto Cody es un niño huérfano adoptado por Jessie y Instituto Cubano del Libro ha organizado de poesía, narración oral y trova, con la del municipio de Marianao, y a las 8:00 p.m., Mark cuyos sueños y pesadillas se manifiestan para este viernes 29 de junio, en la calle conducción de Irasema Cruz Bolaños; Trovada con Sadiel, Celestino, Karel físicamente cuando él duerme. -

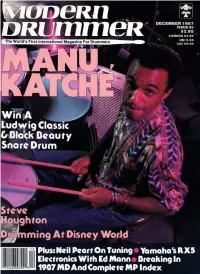

December 1987

VOLUME 11, NUMBER 1 2, ISSUE 98 Cover Photo by Jaeger Kotos EDUCATION IN THE STUDIO Drumheads And Recording Kotos by Craig Krampf 38 SHOW DRUMMERS' SEMINAR Jaeger Get Involved by by Vincent Dee 40 KEYBOARD PERCUSSION Photo In Search Of Time by Dave Samuels 42 THE MACHINE SHOP New Sounds For Your Old Machines by Norman Weinberg 44 ROCK PERSPECTIVES Ringo Starr: The Later Years by Kenny Aronoff 66 ELECTRONIC INSIGHTS Percussive Sound Sources And Synthesis by Ed Mann 68 TAKING CARE OF BUSINESS Breaking In MANU KATCHE by Karen Ervin Pershing 70 One of the highlights of Peter Gabriel's recent So album and ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC tour was French drummer Manu Katche, who has gone on to Two-Surface Riding: Part 2 record with such artists as Sting, Joni Mitchell, and Robbie by Rod Morgenstein 82 Robertson. He tells of his background in France, and explains BASICS why Peter Gabriel is so important to him. Thoughts On Tom Tuning by Connie Fisher 16 by Neil Peart 88 TRACKING DRUMMING AT DISNEY Studio Chart Interpretation by Hank Jaramillo 100 WORLD DRUM SOLOIST When it comes to employment opportunities, you have to Three Solo Intros consider Disney World in Florida, where 45 to 50 drummers by Bobby Cleall 102 are working at any given time. We spoke to several of them JAZZ DRUMMERS' WORKSHOP about their working conditions and the many styles of music Fast And Slow Tempos that are represented there, by Peter Erskine 104 by Rick Van Horn 22 CONCEPTS Drummers Are Special People STEVE HOUGHTON by Roy Burns 116 He's known for his big band work with Woody Herman, EQUIPMENT small-group playing with Scott Henderson, and his teaching at SHOP TALK P.I.T. -

UN Film D'alanté Kavaïté

UN FILM D’ALANTÉ KAVAÏTÉ UFO DISTRIBUTION PRÉSENTE UNE PRODUCTION FRALITA FILMS & LES FILMS D’ANTOINE UN FILM D’ALANTÉ KAVAÏTÉ AVEC AÏSTÉ DIRZIUTÉ, JULIja STEPONAÏTYTÉ MuSIQUE JB DUNCKEL (AIR) SORTIE LE 29 JUILLET 2015 LITUANIE, FRANCE, PAYS-BAs – 2015 – 1h30 FORMAt 1.85 – fORMAT SON 5.1 - DCP Photos et dossier de presse disponibles sur www.ufo-distribution.com DISTRIBUTION PRESSE UFO DISTRIBUTION LAURENCE GRANEC & KARINE MÉNARD TÉL : 01 55 28 88 95 TÉL : 01 47 20 36 66 135, BOULEVARD DE SÉBASTOPOL 92, RUE DE RICHELIEU 75002 PARIS 75002 PARIS [email protected] [email protected] Sangaïlé, jeune fille de 17 ans, passe l’été avec ses parents dans leur villa au bord d’un lac de Lituanie. Comme chaque année, Sangaïlé se rend au show aé- rien. Cette fois, elle y fait la connaissance d’Austé, une fille de son âge, aussi extravertie que Sangaïlé est timide et mal dans sa peau. Une amitié va s’épanouir dans la sensualité de l’été… ENTRETIEN AVEC ALANTÉ KAVAÏTÉ D’OÙ VOUS EST VENUE L’IDÉE DE SUMMER ? Pendant quelques années, dans la région Centre, j’ai animé des ateliers de cinéma avec des adolescents et j’ai éprouvé un grand plaisir à travailler avec eux et surtout à les filmer. Leur capacité à recevoir et à exprimer les choses, avec une intensité qu’on n’a plus à l’âge adulte, m’a vraiment inspirée. J’ai été captivée par leur spontanéité, leur liberté et leur candeur. Cette expérience m’a conduite à repenser à ma propre adolescence en Lituanie.