Lee Hsien Loong V Roy Ngerng Yi Ling [2015]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roy-Ngerngs-Closing-Statement-In

1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE Suit No. 569 of 2014 Between LEE HSIEN LOONG (NRIC NO. S0016646D) …Plaintiff And ROY NGERNG YI LING (NRIC NO. S8113784F) …Defendant DEFENDANT’S CLOSING STATEMENT Solicitors for the Plaintiff Defendant in-Person Mr Davinder Singh S.C. Roy Ngerng Yi Ling Ms Tan Liyun Samantha Ms Cheng Xingyang Angela Mr Imran Rahim Roy Ngerng Yi Ling Drew & Napier LLC Block 354C 10 Collyer Quay #10-01 Admiralty Drive Ocean Financial Centre #14-240 Singapore 049315 Singapore 753354 Tel: 6535 0733 Tel: 9101 2685 Fax: 6535 7149 File Ref: DS/318368 Dated this 31st day of August 2015 2 DEFENDANT’S CLOSING STATEMENT A. Introduction 1. I am Roy. I am 34 this year. Little did I imagine that one day, I would be sued by the prime minister of Singapore. Throughout my whole life, I have tried my very best to live an honest life and to be true to myself and what I believe in. 2. When I was in primary school, I would reach out to my Malay and Indian classmates to make friends with them because I did not want them to feel any different. This continued when I went to secondary school and during my work life. Some of my closest friends have been Singaporeans from the different races. From young, I understand how it feels to be different and I did not want others to feel any differently about who they are. 3. But it is not an easy path in life, for life is about learning and growing as a person, and sometimes life throws challenges at you, and you have to learn to overcome it to become a stronger person. -

Major Vote Swing

BT INFOGRAPHICS GE2015 Major vote swing Bukit Batok Sengkang West SMC SMC Sembawang Punggol East GRC SMC Hougang SMC Marsiling- Nee Soon Yew Tee GRC GRC Chua Chu Kang Ang Mo Kio Holland- GRC GRC Pasir Ris- Bukit Punggol GRC Hong Kah Timah North SMC GRC Aljunied Tampines Bishan- GRC GRC Toa Payoh East Coast GRC GRC West Coast Marine GRC Parade Tanjong Pagar GRC GRC Fengshan SMC MacPherson SMC Mountbatten SMC FOUR-MEMBER GRC Jurong GRC Potong Pasir SMC Chua Chu Kang Registered voters: 119,931; Pioneer Yuhua Bukit Panjang Radin Mas Jalan Besar total votes cast: 110,191; rejected votes: 2,949 SMC SMC SMC SMC SMC 76.89% 23.11% (84,731 votes) (25,460 votes) PEOPLE’S ACTION PARTY (83 SEATS) WORKERS’ PARTY (6 SEATS) PEOPLE’S PEOPLE’S ACTION PARTY POWER PARTY Gan Kim Yong Goh Meng Seng Low Yen Ling Lee Tze Shih SIX-MEMBER GRC Yee Chia Hsing Low Wai Choo Zaqy Mohamad Syafarin Sarif Ang Mo Kio Pasir Ris-Punggol 2011 winner: People’s Action Party (61.20%) Registered voters: 187,771; Registered voters: 187,396; total votes cast: 171,826; rejected votes: 4,887 total votes cast: 171,529; rejected votes: 5,310 East Coast Registered voters: 99,118; 78.63% 21.37% 72.89% 27.11% total votes cast: 90,528; rejected votes: 1,008 (135,115 votes) (36,711 votes) (125,021 votes) (46,508 votes) 60.73% 39.27% (54,981 votes) (35,547 votes) PEOPLE’S THE REFORM PEOPLE’S SINGAPORE ACTION PARTY PARTY ACTION PARTY DEMOCRATIC ALLIANCE Ang Hin Kee Gilbert Goh J Puthucheary Abu Mohamed PEOPLE’S WORKERS’ Darryl David Jesse Loo Ng Chee Meng Arthero Lim ACTION PARTY PARTY Gan -

The Candidates

BT INFOGRAPHICS GE2015 The candidates Bukit Batok Sengkang West SMC SMC Sembawang Punggol East GRC SMC Hougang Marsiling- SMC Yew Tee GRC Nee Soon GRC Chua Chu Kang AngAng Mo MoKio Kio Holland- Pasir Ris- GRC GRCGRC Bukit Punggol GRC Timah Hong Kah GRC North SMC Tampines Bishan- Aljunied GRC Toa Payoh GRC East Coast GRC Jurong GRC GRC West Coast GRC Marine Parade Tanjong Pagar GRC GRC Fengshan SMC FOUR-MEMBER GRC Jalan Besar Chua Chu Kang MacPherson SMC GRC (Estimated no. of electors: 119,848) Mountbatten SMC PEOPLE’S PEOPLE’S ACTION PARTY POWER PARTY Gan Kim Yong Goh Meng Seng Low Yen Ling Lee Tze Shih Pioneer Yuhua Bukit Panjang Radin Mas Potong Yee Chia Hsing Low Wai Choo SMC SMC SMC SMC Pasir SMC Zaqy Mohamad Syafarin Sarif East Coast SIX-MEMBER GRC FIVE-MEMBER GRC FOUR-MEMBER GRC SINGLE-MEMBER CONSTITUENCY (SMC) (Estimated no. electors: 99,015) PEOPLE’S WORKERS’ SIX-MEMBER GRC FIVE-MEMBER GRC ACTION PARTY PARTY Jessica Tan Daniel Goh Ang Mo Kio Aljunied Nee Soon Lee Yi Shyan Gerald Giam (Estimated no. of electors: 187,652) (Estimated no. of electors: 148,024) (Estimated no. of electors: 132,200) Lim Swee Say Leon Perera Maliki Bin Osman Fairoz Shariff PEOPLE’S THE REFORM WORKERS’ PEOPLE’S PEOPLE’S WORKERS’ Holland-Bukit Timah ACTION PARTY PARTY PARTY ACTION PARTY ACTION PARTY PARTY (Estimated no. of electors: 104,397) Ang Hin Kee Gilbert Goh Chen Show Mao Chua Eng Leong Henry Kwek Cheryl Denise Loh Darryl David Jesse Loo Low Thia Kiang K Muralidharan Pillai K Shanmugam Gurmit Singh Gan Thiam Poh M Ravi Faisal Abdul Manap Shamsul Kamar Lee Bee Wah Kenneth Foo Intan Azura Mokhtar Osman Sulaiman Pritam Singh Victor Lye Louis Ng Luke Koh PEOPLE’S SINGAPORE ACTION PARTY DEMOCRATIC PARTY Koh Poh Koon Roy Ngerng Sylvia Lim Yeo Guat Kwang Faishal Ibrahim Ron Tan Christopher De Souza Chee Soon Juan Lee Hsien Loong Siva Chandran Liang Eng Hwa Chong Wai Fung Bishan-Toa Payoh Sembawang Sim Ann Paul Ananth Tambyah Pasir Ris-Punggol (Estimated no. -

Polling Scorecard

Kebun Baru SMC Yio Chu Kang SMC Sembawang GRC Marymount SMC Pulau Punggol West SMC Seletar Pasir Ris- Polling Sengkang GRC Punggol GRC Pulau Tekong Marsiling- Nee Soon Yew Tee GRC GRC Pulau Ubin Pulau Serangoon scorecard Chua Chu Kang GRC Holland- Ang Mo Kio Bukit Panjang Bukit Timah GRC SMC GRC Hong Kah Here’s your guide to the polls. Bukit North SMC Aljunied Tampines Batok GRC GRC You can ll in the results SMC as they are released tonight on Bishan-Toa East Coast Pioneer Payoh GRC GRC str.sg/GE2020-results SMC West Coast GRC Jalan Marine Tanjong Besar Parade Pagar GRC GRC GRC Hougang SMC Mountbatten SMC MacPherson SMC Pulau Brani Jurong Yuhua Jurong Potong Pasir SMC Island SMC GRC 5-member GRCs Radin Mas SMC Sentosa 4-member GRCs Single-member constituencies (SMCs) New GROUP REPRESENTATION CONSTITUENCIES Aljunied 151,007 Ang Mo Kio 185,465 Votes cast Spoilt votes voters Votes cast Spoilt votes voters WP No. of votes: PAP No. of votes: Pritam Singh, 43 Sylvia Lim, 55 Faisal Manap, 45 Gerald Giam, 42 Leon Perera, 49 Lee Hsien Loong, Gan Thiam Poh, 56 Darryl David, 49 Ng Ling Ling, 48 Nadia Samdin, 30 68 PAP No. of votes: RP No. of votes: Victor Lye, 58 Alex Yeo, 41 Shamsul Kamar, Chan Hui Yuh, 44 Chua Eng Leong, Kenneth Andy Zhu, 37 Darren Soh, 52 Noraini Yunus, 52 Charles Yeo, 30 48 49 Jeyaretnam, 61 • Aljunied GRC was won by the WP in 2011, making it the rst GE2015 result: • Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong made his 1984 electoral debut in Teck Ghee GE2015 result: opposition-held GRC. -

The Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association for Disenfranchised Workers Oct

The Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association for Disenfranchised Workers Oct. 2016 thematic report to the UN General Assembly by the Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association QUESTIONS FOR CIVIL SOCIETY/UNIONS/WORKERS Migrant Forum in Asia (MFA), a network of 200+ migrant community organizations, migrants’ rights activists, and trade unions across Asia, thanks the Special Rapporteur for his decision to pay particular attention to the right to freedom of association of vulnerable and disenfranchised workers, including migrant workers. With members and partners working in all regions of Asia, MFA has decided to focus its comments on the countries of the GCC and Singapore—in both contexts, particularly harsh restrictions on freedom of association have had severe and lasting impacts on migrant workers and members of their families. 1. What are the challenges to exercising the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association (FOAA rights) for disenfranchised workers in your country or region? Are there specific gender-related or socio-cultural dimensions to any of these challenges? Specific examples are most helpful. Migrant workers in the GCC countries face many challenges in exercising their rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and association: They often work long hours under difficult working conditions, making it difficult to find time to gather, even socially or for cultural or religious celebrations. They are often socially and physically isolated, particularly when they live in work camps or, in the case of domestic workers, their employers’ homes. In such cases, the monitoring of their activities by their employers frustrates their ability to freely associate. -

Download Publication

SINGAPORE By H R Dipendra 1 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. What were the most important courts decisions on FoE in 2015 in your country/region in terms of their legal reasoning, legal outcome, and/or precedent setting? There are three main judgments on FoE issued last year that were of particular significance: • Public Prosecutor v Amos Yee Pang Sang:The Accused, Amos Yee (aged 16 years old) was charged under Section 298 of the Penal Code which criminalises the uttering of words with the deliberate intent of wounding the religious or racial feelings of any persons. Amos had uploaded a video that accused Lee Kuan Yew, the former Prime Minister of Singapore of being power- hungry and compared him with Christianity. Amos also faced a charge under Section 292(1)(a) of the Penal Code for transmitting by electronic means obscene materials. Amos had created a blog post, entitled “Lee Kuan Yew buttfucking Margaret Thatcher”, and uploaded a Photoshop photo of such an imagery. Amos was sentenced to a total of four weeks’ imprisonment. This case had garnered significant international attention, in part due to the tender age of the Accused. The Un Human Rights Office for instance, expressed its concerned about the case, and called for the immediate release of Amos in line with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which Singapore is a signatory to. • Lee Hsien Loong v Ngerng Yi Ling Roy: The Defendant, Roy Ngerng, had written a blogpost where he compared the Prime Minister of Singapore, Mr. Lee Hsien Loong who is also the Chairman of GIC Private Limited (“GIC”)(which manages Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund), with the leaders of City Harvest Church who were at that point of time being tried for criminal misappropriation. -

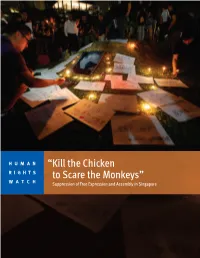

“Kill the Chicken to Scare the Monkeys” Suppression of Free Expression and Assembly in Singapore

HUMAN “Kill the Chicken RIGHTS to Scare the Monkeys” WATCH Suppression of Free Expression and Assembly in Singapore “Kill the Chicken to Scare the Monkeys” Suppression of Free Expression and Assembly in Singapore Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-35522 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org DECEMBER 2017 ISBN: 978-1-6231-35522 “Kill the Chicken to Scare the Monkeys” Suppression of Free Expression and Assembly in Singapore Glossary .............................................................................................................................. i Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Criminal Penalties for Peaceful Speech ................................................................................... -

274KB***Fake News, Free Speech and Finding Constitutional

(2020) 32 SAcLJ 207 (Published on e-First 14 February 2020) FAKE NEWS, FREE SPEECH AND FINDING CONSTITUTIONAL CONGRUENCE In September 2018, the Select Committee on Deliberate Online Falsehoods issued a report that recommended new legislation to address the harms of online falsehood or “fake news”. After much vigorous debate in Parliament, the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (Act 18 of 2019) (“POFMA”) was passed on 8 May 2019 and came into effect on 2 October 2019. As expected, POFMA, like any legislation which attempts to curtail the spread of fake news, has attracted much criticism. As the business models of social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter thrive on community engagement and user-generated content, such technology companies lack the incentive to curb the virality of fake news under a voluntary self-regulation regime. At the same time, fake news laws can overreach and significantly restrict the constitutional right to freedom of speech. This article surveys the efficacy of the legislative landscape pre-POFMA in combating fake news and suggests that an umbrella legislation like POFMA is necessary. This article concludes that POFMA, even if perceived to be draconian, is congruent with Art 14 of the Singapore Constitution (1999 Reprint). Nevertheless, such plenary powers are subject to potentially powerful political limits in the electoral process. The final test for the legitimacy of POFMA really lies in how the Government enforces this new law. David TAN PhD, LLB, BCom (Melbourne), LLM (Harvard); Professor and Vice Dean (Academic Affairs), Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore. Jessica TENG Sijie LLB (Hons) (National University of Singapore), BA (Hons) (Yale-National University of Singapore). -

The Singapore Model

THE SINGAPORE MODEL Vision - Mission - Challenges By Emeritus Professor Dr BR Duncan Commonwealth University for Business, Arts and Technology 2 Table of Contents Summary .................................................................................................................... 3 Statement and Questions ........................................................................................... 4 Foreword ................................................................................................................... 8 Singapore: Credentials ............................................................................................. 11 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 12 Chapter 1. Singapore – the Early Visionaries ........................................................... 17 Chapter 2. A Timeline of Lee Kuan Yew (1923 – 2015) ........................................... 20 Chapter 3. Who was Lee Kuan Yew?....................................................................... 23 Chapter 4. The Crucial Roles of Governance – Bureaucracy, Meritocracy, and Democracy ............................................................................................................... 28 Chapter 5. The Crucial Role of Governance versus Corruption .............................. 42 Chapter 6. The Crucial Role of Governance and the Economy ................................ 48 Chapter 7. The Crucial Role of Governance and Education .................................... -

Lee Hsien Loong V Roy Ngerng Yi Ling

Lee Hsien Loong v Roy Ngerng Yi Ling [2014] SGHC 230 Case Number : Suit No 569 of 2014 (Summons No 3403 of 2014) Decision Date : 07 November 2014 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : Lee Seiu Kin J Counsel Name(s) : Davinder Singh SC, Angela Cheng, Samantha Tan and Imran Rahim (Drew & Napier LLC) for the plaintiff; M Ravi (L F Violet Netto) and Eugene Thuraisingam (Eugene Thuraisingam) for the defendant. Parties : Lee Hsien Loong — Roy Ngerng Yi Ling Tort – Defamation 7 November 2014 Judgment reserved. Lee Seiu Kin J: Introduction 1 The present action arises out of the publication of an article entitled “Where Your CPF Money Is Going: Learning From The City Harvest Trial” (“the Article”) on the blog “The Heart Truths to Keep Singaporeans Thinking by Roy Ngerng” (“the Blog”) on or about 15 May 2014. The plaintiff is the Prime Minister of Singapore and the Chairman of GIC Private Limited (“GIC”). [note: 1] The defendant is the owner and writer of the Blog. [note: 2] 2 The plaintiff filed the writ of summons in this suit on 29 May 2014. The defendant filed his defence on 17 June 2014 and an amended defence on 27 June 2014. Pleadings closed on 4 July 2014 when the plaintiff filed his reply. On 10 July 2014, the plaintiff applied under Summons No 3403 of 2014 (“SUM 3403/2014”) for the Court to determine the natural and ordinary meaning of the certain allegedly defamatory words and images pursuant to O 14 r 12 of the Rules of Court (Cap 322, R5, 2014 Rev Ed) and to grant summary judgment pursuant to O 14 r 1 on the basis that the defendant has no defence to the claim. -

The Singapore Exception

SPECIAL REPORT SINGAPORE July 18th 2015 The Singapore exception 20150718_SRSingapore.indd 1 06/07/2015 12:36 SPECIAL REPORT SINGAPORE The Singapore exception To continue to flourish in its second half-century, South-East Asia’s miracle city-state will need to change its ways, argues Simon Long AT 50, ACCORDING to George Orwell, everyone has the face he de- CONTENTS serves. Singapore, which on August 9th marks its 50th anniversary as an independent country, can be proud ofits youthful vigour. The view from 3 Land and people the infinity pool on the roof of Marina Bay Sands, a three-towered hotel, Seven million is a crowd casino and convention centre, is futuristic. A forest of skyscrapers glints in the sunlight, temples to globalisation bearing the names of some ofits 4 Politics Performance legitimacy prophets—HSBC, UBS, Allianz, Citi. They tower over busy streets where, mostly, traffic flows smoothly. Below is the Marina Barrage, keeping the 6 Social policy sea out ofa reservoir built at the end ofthe Singapore River, which winds The social contract its way through what is left of the old colonial city centre. Into the dis- tance stretch clusters of high-rise blocks, where most Singaporeans live. 7 The economy ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The years that were fat The sea teems with tankers, ferries and containerships. To the west is one Besides those named in the text, of Asia’s busiest container ports and a huge refinery and petrochemical 7 Inequality and some who prefer anonymity, complex; on Singapore’s eastern tip, perhaps the world’s most efficient The rich are always with us the writer would like to thank the airport. -

SINGAPORE Mapping Digital Media: Singapore

COUNTRY REPORT MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: SINGAPORE Mapping Digital Media: Singapore A REPORT BY THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS WRITTEN BY Lau Joon Nie, Trisha Lin, and Low Mei Mei EDITED BY Marius Dragomir and Mark Thompson (Open Society Media Program editors) Graham Watts (regional editor) EDITORIAL COMMISSION Yuen-Ying Chan, Christian S. Nissen, Dusˇan Reljic´, Russell Southwood, Damian Tambini The Editorial Commission is an advisory body. Its members are not responsible for the information or assessments contained in the Mapping Digital Media texts OPEN SOCIETY MEDIA PROGRAM TEAM Meijinder Kaur, program assistant; Morris Lipson, senior legal advisor; and Gordana Jankovic, director OPEN SOCIETY INFORMATION PROGRAM TEAM Vera Franz, senior program manager; Darius Cuplinskas, director 5 July 2013 Contents Mapping Digital Media ..................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 6 Context ............................................................................................................................................. 11 Social Indicators ................................................................................................................................ 13 Economic Indicators ......................................................................................................................... 16 1. Media Consumption: