The Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association for Disenfranchised Workers Oct

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roy-Ngerngs-Closing-Statement-In

1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE Suit No. 569 of 2014 Between LEE HSIEN LOONG (NRIC NO. S0016646D) …Plaintiff And ROY NGERNG YI LING (NRIC NO. S8113784F) …Defendant DEFENDANT’S CLOSING STATEMENT Solicitors for the Plaintiff Defendant in-Person Mr Davinder Singh S.C. Roy Ngerng Yi Ling Ms Tan Liyun Samantha Ms Cheng Xingyang Angela Mr Imran Rahim Roy Ngerng Yi Ling Drew & Napier LLC Block 354C 10 Collyer Quay #10-01 Admiralty Drive Ocean Financial Centre #14-240 Singapore 049315 Singapore 753354 Tel: 6535 0733 Tel: 9101 2685 Fax: 6535 7149 File Ref: DS/318368 Dated this 31st day of August 2015 2 DEFENDANT’S CLOSING STATEMENT A. Introduction 1. I am Roy. I am 34 this year. Little did I imagine that one day, I would be sued by the prime minister of Singapore. Throughout my whole life, I have tried my very best to live an honest life and to be true to myself and what I believe in. 2. When I was in primary school, I would reach out to my Malay and Indian classmates to make friends with them because I did not want them to feel any different. This continued when I went to secondary school and during my work life. Some of my closest friends have been Singaporeans from the different races. From young, I understand how it feels to be different and I did not want others to feel any differently about who they are. 3. But it is not an easy path in life, for life is about learning and growing as a person, and sometimes life throws challenges at you, and you have to learn to overcome it to become a stronger person. -

Countries: Religious Diversity in Canada and Singapore

German Law Journal (2019), 20, pp. 986–1006 doi:10.1017/glj.2019.74 ARTICLE A Tale of Two (Diverse) Countries: Religious Diversity in Canada and Singapore Arif A. Jamal* and Daniel Wong Sheng Jie** (Received 22 April 2019; accepted 29 August 2019) Abstract Both Canada and Singapore express support for—and have the reality of being—multi-cultural, multi-ethnic, and multi-religious; and both jurisdictions have an avowed commitment to the freedom of religion. Yet, this commitment expresses itself in different ways in these two contexts. Although both the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the Singaporean Constitution guarantee the freedom of religion, juridical definitions of what this freedom means may differ quite profoundly. This Article explores and analyzes these two different environments that nonetheless share important features. We argue that the approaches of Singapore and Canada do not fall simply into the categories of being “liberal” or “illiberal,” but instead invite reflection and reconsideration on the concepts of plural- ism, secularism, and liberalism in interesting ways. This Article thus highlights the significance of contex- tual factors in understanding the ways in which religious diversity is dealt with, particularly in Canada and Singapore, but also more generally. Keywords: Canada; Singapore; religious diversity; multiculturalism A. Introduction Singapore and Canada are in vastly different parts of the world but share some salient character- istics. Both are tremendously diverse in ethnic, racial, and—increasingly—religious terms.1 Both countries also embrace their diversity. For example, reference to the multicultural and multi- religious character of both countries is common, both in general social discourse as well as by political actors and state officials. -

Major Vote Swing

BT INFOGRAPHICS GE2015 Major vote swing Bukit Batok Sengkang West SMC SMC Sembawang Punggol East GRC SMC Hougang SMC Marsiling- Nee Soon Yew Tee GRC GRC Chua Chu Kang Ang Mo Kio Holland- GRC GRC Pasir Ris- Bukit Punggol GRC Hong Kah Timah North SMC GRC Aljunied Tampines Bishan- GRC GRC Toa Payoh East Coast GRC GRC West Coast Marine GRC Parade Tanjong Pagar GRC GRC Fengshan SMC MacPherson SMC Mountbatten SMC FOUR-MEMBER GRC Jurong GRC Potong Pasir SMC Chua Chu Kang Registered voters: 119,931; Pioneer Yuhua Bukit Panjang Radin Mas Jalan Besar total votes cast: 110,191; rejected votes: 2,949 SMC SMC SMC SMC SMC 76.89% 23.11% (84,731 votes) (25,460 votes) PEOPLE’S ACTION PARTY (83 SEATS) WORKERS’ PARTY (6 SEATS) PEOPLE’S PEOPLE’S ACTION PARTY POWER PARTY Gan Kim Yong Goh Meng Seng Low Yen Ling Lee Tze Shih SIX-MEMBER GRC Yee Chia Hsing Low Wai Choo Zaqy Mohamad Syafarin Sarif Ang Mo Kio Pasir Ris-Punggol 2011 winner: People’s Action Party (61.20%) Registered voters: 187,771; Registered voters: 187,396; total votes cast: 171,826; rejected votes: 4,887 total votes cast: 171,529; rejected votes: 5,310 East Coast Registered voters: 99,118; 78.63% 21.37% 72.89% 27.11% total votes cast: 90,528; rejected votes: 1,008 (135,115 votes) (36,711 votes) (125,021 votes) (46,508 votes) 60.73% 39.27% (54,981 votes) (35,547 votes) PEOPLE’S THE REFORM PEOPLE’S SINGAPORE ACTION PARTY PARTY ACTION PARTY DEMOCRATIC ALLIANCE Ang Hin Kee Gilbert Goh J Puthucheary Abu Mohamed PEOPLE’S WORKERS’ Darryl David Jesse Loo Ng Chee Meng Arthero Lim ACTION PARTY PARTY Gan -

![Public Prosecutor V Amos Yee Pang Sang [2015] SGDC 215](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5976/public-prosecutor-v-amos-yee-pang-sang-2015-sgdc-215-635976.webp)

Public Prosecutor V Amos Yee Pang Sang [2015] SGDC 215

Public Prosecutor v Amos Yee Pang Sang [2015] SGDC 215 Case Number : MAC No. 902694 & 902695 of 2015 Decision Date : 28 July 2015 Tribunal/Court : District Court Coram : Kaur Jasvender Counsel Name(s) : Hay Hung Chun, Hon Yi & Kelvin Kow Weijie (Deputy Public Prosecutors) for the prosecution; Alfred Dodwell and Chong Jia Hao (Dodwell & Co LLC) and Tan Ngee Wee Ervin (Michael Hwang Chambers LLC) for the accused Parties : Public Prosecutor — Amos Yee Pang Sang 28 July 2015 District Judge Kaur Jasvender: 1 The accused claimed trial to a charge under section 292(1)(a) of the Penal Code (Cap 224) and a charge under section 298 of the Penal Code (Cap 224). He was found guilty and sentenced to one week’s imprisonment on the charge under section 292(1)(a) and to three weeks’ imprisonment on the charge under section 298. Both terms of imprisonment were ordered to run consecutively. The four-week term was backdated and the accused was released on the same day. He has now appealed against the conviction and sentence on both charges. 2 The prosecution and defence agreed to proceed by way of agreed facts (‘ASOF’) and exhibits thus dispensing with the need for any evidence to be called. Accordingly, it was agreed that no adverse inference will be drawn against the accused from not testifying in his defence. 3 In the course of the closing submissions, the defence made reference to the cautioned statement of the accused relating to the section 298 charge recorded on 30 March 2015 at 10.07am. The prosecution objected to the defence making reference to the statement on the ground that it was not part of the ASOF and exhibits. -

The Candidates

BT INFOGRAPHICS GE2015 The candidates Bukit Batok Sengkang West SMC SMC Sembawang Punggol East GRC SMC Hougang Marsiling- SMC Yew Tee GRC Nee Soon GRC Chua Chu Kang AngAng Mo MoKio Kio Holland- Pasir Ris- GRC GRCGRC Bukit Punggol GRC Timah Hong Kah GRC North SMC Tampines Bishan- Aljunied GRC Toa Payoh GRC East Coast GRC Jurong GRC GRC West Coast GRC Marine Parade Tanjong Pagar GRC GRC Fengshan SMC FOUR-MEMBER GRC Jalan Besar Chua Chu Kang MacPherson SMC GRC (Estimated no. of electors: 119,848) Mountbatten SMC PEOPLE’S PEOPLE’S ACTION PARTY POWER PARTY Gan Kim Yong Goh Meng Seng Low Yen Ling Lee Tze Shih Pioneer Yuhua Bukit Panjang Radin Mas Potong Yee Chia Hsing Low Wai Choo SMC SMC SMC SMC Pasir SMC Zaqy Mohamad Syafarin Sarif East Coast SIX-MEMBER GRC FIVE-MEMBER GRC FOUR-MEMBER GRC SINGLE-MEMBER CONSTITUENCY (SMC) (Estimated no. electors: 99,015) PEOPLE’S WORKERS’ SIX-MEMBER GRC FIVE-MEMBER GRC ACTION PARTY PARTY Jessica Tan Daniel Goh Ang Mo Kio Aljunied Nee Soon Lee Yi Shyan Gerald Giam (Estimated no. of electors: 187,652) (Estimated no. of electors: 148,024) (Estimated no. of electors: 132,200) Lim Swee Say Leon Perera Maliki Bin Osman Fairoz Shariff PEOPLE’S THE REFORM WORKERS’ PEOPLE’S PEOPLE’S WORKERS’ Holland-Bukit Timah ACTION PARTY PARTY PARTY ACTION PARTY ACTION PARTY PARTY (Estimated no. of electors: 104,397) Ang Hin Kee Gilbert Goh Chen Show Mao Chua Eng Leong Henry Kwek Cheryl Denise Loh Darryl David Jesse Loo Low Thia Kiang K Muralidharan Pillai K Shanmugam Gurmit Singh Gan Thiam Poh M Ravi Faisal Abdul Manap Shamsul Kamar Lee Bee Wah Kenneth Foo Intan Azura Mokhtar Osman Sulaiman Pritam Singh Victor Lye Louis Ng Luke Koh PEOPLE’S SINGAPORE ACTION PARTY DEMOCRATIC PARTY Koh Poh Koon Roy Ngerng Sylvia Lim Yeo Guat Kwang Faishal Ibrahim Ron Tan Christopher De Souza Chee Soon Juan Lee Hsien Loong Siva Chandran Liang Eng Hwa Chong Wai Fung Bishan-Toa Payoh Sembawang Sim Ann Paul Ananth Tambyah Pasir Ris-Punggol (Estimated no. -

Bee Final Round Bee Final Round Regulation Questions

NHBB A-Set Bee 2016-2017 Bee Final Round Bee Final Round Regulation Questions (1) A letter by Leonel Sharp provides this work's most widely accepted text, including the promises \you have deserved rewards and crowns" and \we shall shortly have a famous victory." In this speech, the speaker thinks \foul scorn that Parma or Spain [...] should dare to invade the borders of my realm" before promising to take up arms, despite having a \weak, feeble" body. For the point, name this 1588 speech delivered to an army awaiting the landing of the Spanish Armada by a leader who had the \heart and stomach of a King," Elizabeth I. ANSWER: Tilbury Speech (accept descriptions that use the name Tilbury; prompt on descriptions that don't, such as \Queen Elizabeth's speech to her army about the incoming Spanish Armada" or portions thereof, so long as the player includes something that the tossup hasn't gotten to yet) (2) This man represented holders of the Wentworth Grants in a New York court case; protecting his interests in those grants led this man and his family to form the Onion River Company. Late in life, this man published the deist book Reason: The Only Oracle of Man. After a meeting at Catamount Tavern, this man organized a militia group that went on to aid Benedict Arnold in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga. For the point, name this man who advocated independence for Vermont and who led the Green Mountain Boys. ANSWER: Ethan Allen (3) This activity was re-affirmed to not be interstate commerce by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. -

Britain's UKIP Loses Only MP

SUNDAY, MARCH 26, 2017 INTERNATIONAL Singaporean teen dissident granted US asylum SINGAPORE: A Singaporean teenager in Singapore,” the judge said in the deci- regards as essential for stability in a who was jailed twice after insulting the sion, a copy of which was seen by AFP. volatile region. island’s late leader Lee Kuan Yew and reli- The judge said evidence presented Several government critics have gious groups has been granted political during the hearing “demonstrates sought refuge overseas, including in the asylum in the United States, his US lawyer Singapore’s persecution of Yee was a pre- United States and Britain, among them said yesterday. Amos Yee, 18, shocked text to silence his political opinions criti- Gopalan Nair who was granted US asy- Singaporeans in March 2015 after posting cal of the Singapore government”. The lum for political persecution in the 1990s an expletive-laden video attacking Lee as US Department of Homeland Security and now holds American citizenship. Yee, the founding prime minister’s death trig- had opposed Yee’s asylum application, a filmmaker-turned-activist, was gered a massive outpouring of grief in the saying he was legally prosecuted by the detained by US authorities after he city-state. He was jailed for four weeks for Singapore government. It now has 30 arrived in Chicago in December. hurting the religious feelings of Christians days to appeal the judge’s decision. In a Speaking by telephone from Maryland, and posting an obscene image as part of statement yesterday, Singapore’s home lawyer Grossman, who has represented his attacks on Lee-whose son Lee Hsien affairs ministry, which looks after internal Yee for free, said the US government “has Loong is now the prime minister-but security, said Yee had engaged in “hate the right to appeal this decision” within served 50 days including penalties for vio- speech” but noted that such rhetoric is the next 30 days. -

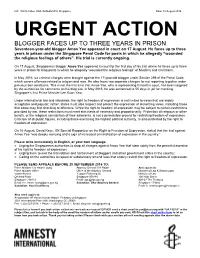

URGENT ACTION BLOGGER FACES up to THREE YEARS in PRISON Seventeen-Year-Old Blogger Amos Yee Appeared in Court on 17 August

UA: 192/16 Index: ASA 36/4685/2016 Singapore Date: 18 August 2016 URGENT ACTION BLOGGER FACES UP TO THREE YEARS IN PRISON Seventeen-year-old blogger Amos Yee appeared in court on 17 August. He faces up to three years in prison under the Singapore Penal Code for posts in which he allegedly “wounded the religious feelings of others”. His trial is currently ongoing. On 17 August, Singaporean blogger Amos Yee appeared in court for the first day of his trial where he faces up to three years in prison for blog posts in which he allegedly “wounded the religious feelings” of Muslims and Christians. In May 2016, six criminal charges were brought against the 17-year-old blogger under Section 298 of the Penal Code, which covers offences related to religion and race. He also faces two separate charges for not reporting to police under previous bail conditions. This is not the first time that Amos Yee, who is representing himself in court, has been targeted by the authorities for comments on his blog site. In May 2015, he was sentenced to 55 days in jail for mocking Singapore’s first Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. Under international law and standards, the right to freedom of expression is not limited to views that are widely acceptable and popular, rather, states must also respect and protect the expression of dissenting views, including those that some may find shocking or offensive. While the right to freedom of expression may be subject to certain restrictions provided by law, these restrictions must meet strict tests of necessity and proportionality. -

Country Report for Singapore

Singapore Singapore Chang Ya Lan* Introduction Singapore is a paradox of a modern city-state. It sits within a discordant clash of values and an uneasy mediation of seemingly contradictory impulses. It is one of the most open and developed countries in Asia and the third richest country in the world,1 with a world-class infrastructure and a highly educated populace. Yet, there are darker facets to Singapore’s sprawling ‘First World-ness’ that gradually chip away at its image as a progressive modern city-state: the government continues to place restrictions on civil and political rights; it retains the use of the death penalty and caning; and in a country that relies heavily on foreign labour, the rights of migrant workers receive shockingly scant protection. Indeed, the Singapore government has long eschewed liberal human rights for a ‘communitarian’ approach.2 However, without a clear articulation of how competing interests are to be negotiated, ‘communitarian’ human rights sacrifice some segments of Singapore society for little compelling reason. As this chapter will demonstrate, a more attractive approach to rights would be one that follows, in principle, the Dworkinian directive of treating people ‘with equal concern and respect.’3 * PhD candidate, University of Cambridge; LLM (London School of Economics); LLB (Hons) (National University of Singapore). I would like to thank Ryan Nicholas Hong Yongsen for his invaluable and tireless research assistance in the writing of this chapter. 1 ‘The 23 richest countries in the world’ Business Insider, 13 July 2015, available at http://www. businessinsider.sg/the-23-richest-countries-in-the-world-2015-7/#.VcBl1_mqpBd, accessed on 31 August 2015. -

Rongxiang Lin Self-Employed Computer Engineer Received

Written Representation 5 Name: Rongxiang Lin Self-employed computer engineer Received: 17 Jan 2018 Title: Select Committee on Deliberate Online Falsehoods - Causes, Consequences and Countermeasures Dear Clerk of Parliament, I type in support of Minister K Shanmugam's speech in parliament and with reference to the Green Paper presented to Parliament on "Deliberate Online Falsehoods: Challenges and Implications" (Misc. 10 of 2018). In this voluntary contribution, I declare that I have absolutely no interest, in fact am utterly dispassionate about this subject matter, yet, am contributing within my abilities, limits and means. I am a trained and certified United Nations sustainable development framework specialist, and I have also served in the capacity of a top secret unit at HQ Mindef leading up to the War on Terror. I reported directly to Mr. Ng Yat Chung, who is now the Chief Executive of Singapore Press Holdings, as well as several key commanders such as Mr. Desmond Kuek as well as my then Commanding Officer Alvin Kek who is assisting Mr. Kuek at SMRT lately, several retired generals such as Mr. Lim Feng and Mr. Hugh Lim U Yang who is CEO Building and Construction Authority, and more poignantly also Mr. Ravinder Singh who was the first minority Chief of Army in Singapore. Mr. Lee Kuan Yew once said approximately, "Freedom of the press, freedom of the news media, must be subordinated to the overriding needs of the integrity of Singapore, and to the primacy of purpose of an elected government." I have never been a fan of press freedom and will never be. -

Working Paper Series

東南亞研究中心 Southeast Asia Research Centre Cherian GEORGE Hong Kong Baptist University Hong Kong Managing Religious Diversity in South East Asia: How Insult Laws Backfire Working Paper Series No. 175 May 2016 Managing Religious Diversity in South East Asia: How Insult Laws Backfire CHERIAN GEORGE Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong Abstract Incidents such as the 2015 murder of Charlie Hebdo cartoonists prompted many liberals to rethink the proper balance between freedom of expression and respect for religion. In the present climate, marked by anxiety over the extreme violence that accompanies religious offence, it may appear that diverse societies have no choice but to sacrifice free speech for the sake of peaceful relations among different communities. Indeed, this has been the conventional wisdom in many Asian societies. This article, however, challenges the view that the law should step in when communities claim that their religious feelings have been offended. Referring to the experiences of Indonesia and Singapore, it argues that the criminalisation of religious offence—through blasphemy, sedition and other laws—tends to be exploited by political actors against their opponents, often at the expense of religious minorities or other marginalised groups. Introduction One of the most successful franchises in modern political drama combines the themes of free speech and religious offence. These highly charged performances involve threats to public order—sometimes including bloody violence—and calls for censorship. The most famous examples from the past decade were the controversies around the Charlie Hebdo satirical magazine, the Innocence of Muslims YouTube video, and the Danish newspaper cartoons. Many more such incidents have taken place at the domestic level. -

Digital Protest in Singapore: the Pragmatics of Political Internet Memes

MCS0010.1177/0163443720904603Media, Culture & SocietySoh 904603research-article2020 Main Article Media, Culture & Society 1 –18 Digital protest in Singapore: © The Author(s) 2020 Article reuse guidelines: the pragmatics of political sagepub.com/journals-permissions https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720904603DOI: 10.1177/0163443720904603 Internet memes journals.sagepub.com/home/mcs Wee Yang Soh The University of Chicago, USA Abstract This article investigates the use of Internet memes as political protest in Singapore. The proliferation of political memes after the controversial 2017 Singapore presidential election was curious, considering the government’s strict policies in regulating discourses both online and offline. By analyzing memes that circulated after the election, this article examines how the aesthetic form of political Internet memes intersects with current communicative ideologies to disperse their authorship, thereby allowing Singaporeans to communicate political dissent indirectly in ways that can always be subsequently disavowed as humor. In particular, the political productiveness of memes stems from their ambivalent status, as they are capable of being evaluated according to two competing ideologies centered on two intensional prototypes: first, of memes as political artifacts; second, of memes as humorous artifacts. Empirically, this article builds on existing digital media scholarship by demonstrating the need to factor language and media ideologies into analyses of digital media. Keywords censorship, digital technologies, Internet memes, Internet studies, media ideology, protest movements, Singapore, social media Introduction On 11 September 2017, Halimah Yacob, a member of Singapore’s ruling People’s Action Party (PAP), was declared the country’s President-elect. Although there had been two other potential candidates in the running, Halimah’s election was not achieved at the polls, Corresponding author: Wee Yang Soh, The Department of Anthropology, The University of Chicago, 1126 East 59th Street, Chicago, IL 60637, USA.