Draft Evaluation of the Ghana Food For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Family Histories from the Banda Traditional Area, Brong-Ahafo

Family Histories from the Banda Traditional Area, Brong-Ahafo Region, Ghana 1986 Recorded by: Ann Stahl, Assistant Professor Department of Anthropology State University of New York, Binghamton Binghamton, NY USA Translated by: James Anane, Project Director Nafaanra Literacy Project Banda-Ahenkro Brong-Ahafo Region, Ghana First Circulated 1989 Reissued with Photos & Additional Histories 2011 DEDICATION This collection is dedicated to the elderly people and Elders of Banda -- those remarkable men and women who are repositories of stories about the past. The people of Banda have in their midst individuals who are exceptional sources of information about the history of the Banda peoples. Most of these people are elderly, and it is hoped that the younger generations of Banda will pause to listen, to take notice and remember the traditons of previous generations. i A Note on 2011 Reissue of “Family Histories from the Banda Traditional Area” Most of the family histories in this volume were first circulated in a typescript booklet produced in 1989 based on interviews conducted as part of a family history project conducted with the research assistance of Mr. James Anane in 1986. The archaeological project that followed our family history research has now spanned more than two decades. While in Banda conducting archaeological research in 2009, I was asked by individuals in the community if it would be possible to reissue the family history booklet because the original printing had limited circulation and many of the original copies lost or misplaced. Over the years while pursuing archaeological research, additional families had requested that their family histories be included if a revised version of the booklet was ever produced. -

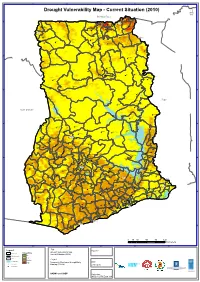

Drought Vulnerability

3°0'0"W 2°0'0"W 1°0'0"W 0°0'0" 1°0'0"E Drought Vulnerability Map - Current Situation (2010) ´ Burkina Faso Pusiga Bawku N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Gwollu Paga ° 1 1 1 1 Zebilla Bongo Navrongo Tumu Nangodi Nandom Garu Lambusie Bolgatanga Sandema ^_ Tongo Lawra Jirapa Gambaga Bunkpurugu Fumbisi Issa Nadawli Walewale Funsi Yagaba Chereponi ^_Wa N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 0 0 1 1 Karaga Gushiegu Wenchiau Saboba Savelugu Kumbungu Daboya Yendi Tolon Sagnerigu Tamale Sang ^_ Tatale Zabzugu Sawla Damongo Bole N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 9 9 Bimbila Buipe Wulensi Togo Salaga Kpasa Kpandai Côte d'Ivoire Nkwanta Yeji Banda Ahenkro Chindiri Dambai Kintampo N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 8 Sampa 8 Jema Nsawkaw Kete-krachi Kajeji Atebubu Wenchi Kwame Danso Busunya Drobo Techiman Nkoranza Kadjebi Berekum Akumadan Jasikan Odumase Ejura Sunyani Wamfie ^_ Dormaa Ahenkro Duayaw Nkwanta Hohoe Bechem Nkonya Ahenkro Mampong Ashanti Drobonso Donkorkrom Nkrankwanta N N " Tepa Nsuta " 0 Va Golokwati 0 ' Kpandu ' 0 0 ° Kenyase No. 1 ° 7 7 Hwediem Ofinso Tease Agona AkrofosoKumawu Anfoega Effiduase Adaborkrom Mankranso Kodie Goaso Mamponteng Agogo Ejisu Kukuom Kumasi Essam- Debiso Nkawie ^_ Abetifi Kpeve Foase Kokoben Konongo-odumase Nyinahin Ho Juaso Mpraeso ^_ Kuntenase Nkawkaw Kpetoe Manso Nkwanta Bibiani Bekwai Adaklu Waya Asiwa Begoro Asesewa Ave Dapka Jacobu New Abirem Juabeso Kwabeng Fomena Atimpoku Bodi Dzodze Sefwi Wiawso Obuasi Ofoase Diaso Kibi Dadieso Akatsi Kade Koforidua Somanya Denu Bator Dugame New Edubiase ^_ Adidome Akontombra Akwatia Suhum N N " " 0 Sogakope 0 -

2021 PES Field Officer's Manual Download

2021 POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS POST ENUMERATION SURVEY (PES) FIELD OFFICER’S MANUAL STATISTICAL SERVICE, ACCRA July, 2021 1 Table of Content LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................... 11 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 12 CHAPTER 1 ................................................................................................................. 13 1. THE CONCEPT OF PES AND OVERVIEW OF CENSUS EVALUATION ........................ 13 1.1 What is a Population census? .................................................................................................. 13 1.2 Why are we conducting the Census? ...................................................................................... 13 1.3. Census errors .............................................................................................................................. 13 1.3.1. Omissions ................................................................................................................................. 14 1.3.2. Duplications ............................................................................................................................. 14 1.3.3. Erroneous inclusions ............................................................................................................... 15 1.3.4. Gross versus net error ............................................................................................................ -

Council for Scientific and Industrial Research Soil

COUNCIL FOR SCIENTIFIC AND INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH SOIL RESEARCH INSTITUTE REPORT ON THE SOIL RESOURCES OF TAIN DISTRICT, BRONG AHAFO REGION, GHANA (CSIR / WAAPP NO. 017) Project Team: James Kofi Senayah (Leader), K. Abrefa Nketia, Emmanuel Amoakwa, Johnny Awoonor, Anim Boafo, Kwadaso, Kumasi May, 2013 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Information Soil information is basic to several economic sectors such as farming, establishment of pastures, forestry, construction of fish pond, mining activities, etc. Soil maps provide a quick summary of soil information that assists in determining the suitability or potential of an area for any agricultural and other related land-use. They are guides to investors and planning tools for agricultural planners. The work on the Tain District in the Brong Ahafo Region, seeks to provide a more detailed soil and related information that will provide relevant information as input in the preparation of any development plan for the district and also provide quick information on potential agricultural and other landuse areas. Tain District occurs within the Tain River Basin Soil Survey Region of the CSIR-Soil Research Institute. It is a recently created district that requires knowledge on its natural resources to assist in its quest for development and a boost in economic activities. The District is basically agriculturally oriented but has little information on its soil resources due to its remoteness until the recent construction of the Bui dam. Basic soil information which provided the baseline data for this study is the draft report of the detailed reconnaissance soil survey of the Tain River Basin and a soil map (1997) available at the CSIR-Soil Research Institute. -

GES-SHS-Selection-REGISTER-2019

CATEGORY A PROGRAMMES NO. SCHOOL AGRI HOM. VIS. GEN. GEN. OF S/N REGION DISTRICT SCHOOL NAME LOCATION GENDER BUS TECH STATUS CODE C ECONS ARTS ARTS SCI PROG S 101 201 301 401 402 501 502 1 AHAFO Asutifi North 0061201 OLA Girls Senior High, Kenyasi Kenyasi Girls X X X X 4 Day/Boarding 2 AHAFO Tano North 0060203 Serwaa Kesse Girls Senior High Duayaw Nkwanta Girls X X X X X X 6 Day/Boarding 3 ASHANTI Kumasi Metro 0050102 St. Louis Senior High, Kumasi Oduom-Kumasi Girls X X X X X 5 Day/Boarding 4 ASHANTI Kumasi Metro 0050111 Kumasi Senior High Gyinyase-Kumasi Boys X X X X X 5 Day/Boarding 5 ASHANTI Kumasi Metro 0050110 Opoku Ware Senior High Santasi-Kumasi Boys X X X X 4 Day/Boarding 6 ASHANTI Kumasi Metro 0050108 Prempeh College Sofoline-Kumasi Boys X X X X 4 Day/Boarding 7 ASHANTI Kumasi Metro 0050104 T. I. Ahmadiyya Senior High , Kumasi Kumasi - Stadium Mixed X X X X X X 6 Day/Boarding 8 ASHANTI Kumasi Metro 0050201 Yaa Asantewaa Girls Senior High . Tanoso-Kumasi Girls X X X X X X 6 Day/Boarding 9 B. AHAFO Berekum-Municipal 0060303 Berekum Presby Senior High Berekum Mixed X X X X X X 6 Day/Boarding 10 B. AHAFO Jaman North 0060513 St. Ann's Girls Senior High, Sampa Sampa Girls X X 2 Day 11 B. AHAFO Jaman South 0060505 Our Lady of Providence Senior High Kwasi Buokrom Girls X X X X 4 Day/Boarding 12 B. -

Report of the Commission of Inquiry Into the Creation of New Regions

COMMISSION OF INQUIRY REPORT OF THE COMMISSION OF INQUIRY INTO THE CREATION OF NEW REGIONS EQUITABLE DISTRIBUTION OF NATIONAL RESOURCES FOR BALANCED DEVELOPMENT PRESENTED TO HIS EXCELLENCY THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF GHANA NANA ADDO DANKWA AKUFO-ADDO ON TUESDAY, 26TH DAY OF JUNE, 2018 COMMISSION OF INQUIRY INTO In case of reply, the CREATION OF NEW REGIONS number and date of this Tel: 0302-906404 Letter should be quoted Email: [email protected] Our Ref: Your Ref: REPUBLIC OF GHANA 26th June, 2018 H.E. President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo President of the Republic of Ghana Jubilee House Accra Dear Mr. President, SUBMISSION OF THE REPORT OF THE COMMISSION OF INQUIRY INTO THE CREATION OF NEW REGIONS You appointed this Commission of Inquiry into the Creation of New Regions (Commission) on 19th October, 2017. The mandate of the Commission was to inquire into six petitions received from Brong-Ahafo, Northern, Volta and Western Regions demanding the creation of new regions. In furtherance of our mandate, the Commission embarked on broad consultations with all six petitioners and other stakeholders to arrive at its conclusions and recommendations. The Commission established substantial demand and need in all six areas from which the petitions emanated. On the basis of the foregoing, the Commission recommends the creation of six new regions out of the following regions: Brong-Ahafo; Northern; Volta and Western Regions. Mr. President, it is with great pleasure and honour that we forward to you, under the cover of this letter, our report titled: “Equitable Distribution of National Resources for Balanced Development”. -

Office of Government Machinery

REPUBLIC OF GHANA MEDIUM TERM EXPENDITURE FRAMEWORK (MTEF) FOR 2021-2024 OFFICE OF GOVERNMENT MACHINERY PROGRAMME BASED BUDGET ESTIMATES For 2021 Transforming Ghana Beyond Aid REPUBLIC OF GHANA Finance Drive, Ministries-Accra Digital Address: GA - 144-2024 MB40, Accra - Ghana +233 302-747-197 [email protected] mofep.gov.gh Stay Safe: Protect yourself and others © 2021. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be stored in a retrieval system or Observe the COVID-19 Health and Safety Protocols transmitted in any or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the Ministry of Finance Get Vaccinated OFFICE OF GOVERNMENT MACHINERY The OGM MTEF PBB for 2021 is also available on the internet at: www.mofep.gov.gh ii | 2021 BUDGET ESTIMATES Contents PART A: STRATEGIC OVERVIEW OF THE OFFICE OF GOVERNMENT MACHINERY (OGM) ................................................................................................... 2 1. POLICY OBJECTIVES ..................................................................................... 2 2. GOAL ................................................................................................................ 2 3. CORE FUNCTIONS .......................................................................................... 2 4. POLICY OUTCOME INDICATORS AND TARGETS ....................................... 3 POLICY OUTCOME INDICATORS AND TARGETS (MINISTRY OF SPECIAL INITIATIVE AND DEVELOPMENT) ..................................................................... -

Staff-ID-For-Bono

BRONG AHAFO-1607 S/N STAFF ID FULL_NAME MANAGEMENT_UNIT DISTRICT 1 1417193 FOSUAA, Mrs. JEMIMA 0725 Bongase DA KG & Prim Banda 2 1417184 TETTEH, Mr. ISAAC KWESI 0725 Bongase DA KG & Prim Banda 3 1417178 ANDAMAH, Mr. MUSAH 0725 Dorbor DA Prim Banda 4 1417183 ABIIKARO, Mrs. BARBARA 0725 Banda-AhenkroGbao DA Prim Dist Educ Banda 5 1417189 AFRIYIE, Miss MAVIS 0725Office Banda-Ahenkro Dist Educ Banda 6 1417199 KYERAA, Mrs. RITA 0725Office Banda-Ahenkro Dist Educ Banda 7 1417174 ASIEDU, Mr. PRINCE Office Banda 0725 Bandaman Senior High Tech 8 1416532 NSIAH ABABIO, Mrs. GLORIA 0725Sch Bandaman Senior High Tech Banda 9 1416539 BOAKYE, Mr. ERIC 0725Sch Bandaman Senior High Tech Banda 10 1416544 BEKOE, Mr. RICHARD 0725Sch Bandaman Senior High Tech Banda 11 1416521 BOATENG, Mr. SAMUEL 0725Sch Bandaman Senior High Tech Banda 12 1416550 MOSES, Mr. SIE KWAKU Sch Banda BOAMPONG, Mr. RICHARD 0725 Bandaman Senior High Tech 13 1416534 ANOMAH Sch Banda 0725 Bandaman Senior High Tech 14 1416527 GYAMFI, Mr. MICHAEL KWASI 0725Sch Bandaman Senior High Tech Banda 15 1416524 ASIEDU, Mr. MICHAEL Sch Banda 16 1417169 OBENG, Mr. ISAAC BOATENG 0725 Sanwa Makala DA Prim Banda 17 1417225 KYEREH, Mr. STEPHEN 0725 Sanwa Makala DA Prim Banda 18 1417216 FUSENI, Miss MUNIRATU 0725 Banda Ahenkro Meth Prim Banda 19 1417214 TIEREOFAA, Mr. MWINKUM 0725 Banda Ahenkro Meth Prim Banda 20 1417220 BOSEAH, Mr. MOSES 0725 Banda Ahenkro Presby Prim Banda 21 1417208 ASANTE, Mr. MICHAEL 0725 Banda Ahenkro Presby Prim Banda OSEI, Mr. ORPHEAUS 22 1417204 SARPONG 0725 Kojee Presby Prim Banda Berekum Municipal 23 1418346 WEJENAKA, Miss RITA 0705 Amomaso MA Prim (GOV) Assembly Berekum NINFAM, Mr. -

Coalition of Domestic Election Observers (CODEO)

Coalition of Domestic Election Observers (CODEO) CONTACT Secretariat: +233 (0) 244 350 266/ 0277 744 777 Email:[email protected]: Website: www.codeoghana.org PRELIMINARY REPORTSTATEMENT (1) ON THE ON ON-GOING THE VOTER BIOMETRIC REGISTER VOTER REGISTRATION EXERCISE BY THE ELECTORAL COMMISSION The Coalition of Domestic Election Observers (CODEO) deployed 100 observers for the on- going Biometric Voter Registration (BVR) Exercise being carried out by the Electoral Commission of Ghana (EC) across the country. CODEO has an observer each in 100 randomly and purposively selected constituencies spread across the 16 regions of the country. During Phase One of the registration exercise (June 30-July 5) which just ended, each observer followed one EC registration team and observed the process at one registration center throughout the six days. Observers filed daily observation reports to the CODEO Secretariat in Accra. In addition to the 100 stationery observers, CODEO also had a few roaming observers in the Greater Accra region who observed the registration exercise at some centers in the national capital. In assessing the conduct of the exercise, all CODEO observers are required to observe and report on some key indicators such as the location of registration centers, availability of registration materials, availability and functioning of BVR kits, conduct of registration officials and other stakeholders such as political party agents and registration applicants, and adherence to registration rules and regulations. Observers are also to watch the extent of adherence to COVID-19 health and safety protocols including those instituted by the EC at registration centers. At the end of Phase One of the registration exercise, the CODEO Secretariat received a total of 575 daily observation reports from 100 constituencies from the 30th of June to July 5, 2020. -

The Office of the Head of Local Government Service

REPUBLIC OF GHANA THE OFFICE OF THE HEAD OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT SERVICE MEDIUM TERM EXPENDITURE FRAMEWORK (MTEF) FOR 2017-2019 2017 BUDGET ESTIMATES For copies of the LGS MTEF PBB Estimates, please contact the Public Relations Office of the Ministry: Ministry of Finance Public Relations Office New Building, Ground Floor, Room 001/ 003 P. O. Box MB 40, Accra – Ghana The LGS MTEF PBB Estimate for 2017 is also available on the internet at: www.mofep.gov.gh Local Government Service Page ii Table of Contents PART A: STRATEGIC OVERVIEW OF THE OFFICE OF THE HEAD OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT SERVICE (OHLGS) .......................................................................................1 1. GSGDA II POLICY OBJECTIVES .............................................................................. 1 2. GOAL .................................................................................................................. 1 3. CORE FUNCTIONS ............................................................................................... 1 4. POLICY OUTCOME INDICATORS AND TARGETS .................................................... 2 5. EXPENDITURE TRENDS ......................................................................................... 3 6. KEY ACHIEVEMENTS FOR 2016 ............................................................................ 4 PART B: BUDGET PROGRAM SUMMARY ...........................................................................5 PROGRAM 1: MANAGEMENT AND ADMINISTRATION .................................................. 5 PROGRAMME -

Manufacturing Capabilities in Ghana's Districts

Manufacturing capabilities in Ghana’s districts A guidebook for “One District One Factory” James Dzansi David Lagakos Isaac Otoo Henry Telli Cynthia Zindam May 2018 When citing this publication please use the title and the following reference number: F-33420-GHA-1 About the Authors James Dzansi is a Country Economist at the International Growth Centre (IGC), Ghana. He works with researchers and policymakers to promote evidence-based policy. Before joining the IGC, James worked for the UK’s Department of Energy and Climate Change, where he led several analyses to inform UK energy policy. Previously, he served as a lecturer at the Jonkoping International Business School. His research interests are in development economics, corporate governance, energy economics, and energy policy. James holds a PhD, MSc, and BA in economics and LLM in petroleum taxation and finance. David Lagakos is an associate professor of economics at the University of California San Diego (UCSD). He received his PhD in economics from UCLA. He is also the lead academic for IGC-Ghana. He has previously held positions at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis as well as Arizona State University, and is currently a research associate with the Economic Fluctuations and Growth Group at the National Bureau of Economic Research. His research focuses on macroeconomic and growth theory. Much of his recent work examines productivity, particularly as it relates to agriculture and developing economies, as well as human capital. Isaac Otoo is a research assistant who works with the team in Ghana. He has an MPhil (Economics) from the University of Ghana and his thesis/dissertation tittle was “Fiscal Decentralization and Efficiency of the Local Government in Ghana.” He has an interest in issues concerning local government and efficiency. -

Certified Electrical Wiring Professionals Brong Ahafo Regional Register

CERTIFIED ELECTRICAL WIRING PROFESSIONALS BRONG AHAFO REGIONAL REGISTER NO NAME PHONE NUMBER PLACE OF WORK PIN NUMBER CERTFICATION CLASS 1 ABDALLA NUHU TWENE 0247779276 BONSU EC/CEWP1/06/17/0003 DOMESTIC 2 ABDALLA NUHU TWENE 0247779276 BONSU EC/CEWP1/06/17/0003 DOMESTIC 3 ABDEEN HASSAN 0208435255 WENCHI EC/CEWP1/12/16/0005 DOMESTIC 4 ABDUL KARIM ABDUL MUMIN 0208027284 SUNYANI EC/CEWP1/12/18/0003 DOMESTIC 5 ABDUL MUTALABI OSMAN 0262519200 KINTAMPO EC/CEWP1/12/18/0004 DOMESTIC 6 ABDULAI AKWASI DANIEL 0558788424 SUNYANI EC/CEWP1/06/18/0010 DOMESTIC 7 ABDULAI AMORU DIMAH 0200888883 SUNYANI EC/CEWP2/06/17/003 COMMERCIAL 8 ABDULAI BRAIMAH 0249289312 TECHIMAN EC/CEWP2/06/19/0004 COMMERCIAL 9 ABDULAI-BABA LOSINA WATARA 0208306812 WENCHI EC/CEWP1/12/14/0009 DOMESTIC 10 ABDUL-LATIF ALI 0543141484 SANKORE EC/CEWP1/12/19/0252 DOMESTIC 11 ABDUL-LATIF SALIFU 0549357585 SUNYANI EC/CEWP2/12/19/0133 COMMERCIAL 12 ABDUL-MAJEED IDDRISU 0248828142 NKRONZA SOUTH EC/CEWP1/12/17/0013 DOMESTIC 13 ABOAGYE ERIC 0209097188 WENCHI EC/CEWP1/06/14/0003 DOMESTIC 14 ABOAGYE SOLOMON 0245132173 NTOFROSO-GYEDU EC/CEWP1/06/15/0012 DOMESTIC 15 ABOBA EMMANUEL KWADWO 0247401615 BOMAA EC/CEWP2/06/17/005 COMMERCIAL 16 ABREFAH NOAH 0246840008 TECHIMAN EC/CEWP1/12/14/0014 DOMESTIC 17 ABU SADIQUE 0208430808 TECHIMAN EC/CEWP1/12/16/0016 DOMESTIC 18 ABUBAKAR ABDUL LATIF 0558673115 EJURA EC/CEWP1/06/18/0023 DOMESTIC 19 ABUBAKAR MUNTARI GAMPENI 0248987874 TECHIMAN EC/CEWP1/06/18/0024 DOMESTIC 20 ABUBAKARI ABDULAI 0556477822 TECHIMAN EC/CEWP2/12/17/0008 COMMERCIAL 21 ABUBAKARI FUSEINI