Macbeth and the Gunpowder Plot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gunpowder Plot Activity Pack

TTHHEE GGUUNNPPOOWWDDEERR PPLLOOTT The Gunpowder Plot Activity Pack Welcome to Heritage Doncaster’s the Gunpowder Plot activity pack. This booklet is filled with ideas that you can have a go at as a family at home whilst learning about the Gunpowder Plot. Some of these activities will require adult supervision as they require using an oven, a sharp implement, or could just be a bit tricky these have been marked with this warning triangle. We would love to see what you create so why not share your photos with us on social media or email You can find us at @doncastermuseum @DoncasterMuseum [email protected] Have Fun! Heritage Doncaster Education Service Contents What was the Gunpower Plot? Page 3 The Plotters Page 4 Plotters Top Trumps Page 5-6 Remember, remember Page 7 Acrostic poem Page 8 Tunnels Page 9 Build a tunnel Page 10 Mysterious letter Page 11 Letter writing Page 12 Escape and capture Page 13 Wanted! Page 14 Create a boardgame Page 15 Guy Fawkes Night Page 16 Firework art Page 17-18 Rocket experiment Page 19 Penny for a Guy Page 20 Sew your own Guy Page 21 Traditional Bonfire Night food Page 22 Chocolate covered apples Page 23 Wordsearch Page 24 What was the Gunpowder Plot? The Gunpowder Plot was a plan made by thirteen men to blow up the Houses of Parliament when King James I was inside. The Houses of Parliament is an important building in London where the government meet. It is made up of the House of Lords and the House of Commons. -

History of London Timeline Cut out the Following Cards and Glue Them in the Correct Order on the Timeline

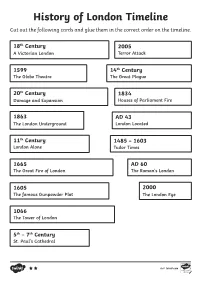

History of London Timeline Cut out the following cards and glue them in the correct order on the timeline. 18th Century 2005 A Victorian London Terror Attack 1599 14th Century The Globe Theatre The Great Plague 20th Century 1834 Damage and Expansion Houses of Parliament Fire 1863 AD 43 The London Underground London Located 11th Century 1485 – 1603 London Alone Tudor Times 1665 AD 60 The Great Fire of London The Roman’s London 1605 2000 The famous Gunpowder Plot The London Eye 1066 The Tower of London 5th – 7th Century St. Paul’s Cathedral visit twinkl.com This famous theatre is where many Unfortunately, there was lots of damage to of William Shakespeare’s plays were London due to bombings during the Second performed. However, in 1613, it was World War including to St. Paul’s Cathedral. burnt down by a staged cannon fire in London once again expanded and many one of his plays. Today, a new 1990s big department stores such as Harrods and Globe Theatre, close to the original Selfridges were built. building, still holds performances of Shakespeare’s plays. 200 years after Guy Fawkes tried to Due to its trading links, Britain and London blow up the Houses of Parliament, became very powerful with goods from all over an accidental fire spread through the world being imported. the main building leaving only Westminster Hall undamaged. The th During the 18 century and Queen Victoria’s replacement was built ten years reign, the population of London expanded and later and still remains there today. many of the buildings we still see in London today were built during the Victorian times. -

History of the Gunpowder Plot & Guy Fawkes Night Four Hundred Years Ago, in 1605, a Man Called Guy Fawkes and a Group Of

History of the Gunpowder Plot & Guy Fawkes Night Four hundred years ago, in 1605, a man called Guy Fawkes and a group of plotters attempted to blow up the Houses of Parliament in London with barrels of gunpowder placed in the basement. They wanted to kill King James and the king’s leaders. Houses of Parliament, London Why did Guy Fawkes want to kill King James 1st and the king’s leaders? When Queen Elizabeth 1st took the throne of England she made some laws against the Roman Catholics. Guy Fawkes was one of a small group of Catholics who felt that the government was treating Roman Catholics unfairly. They hoped that King James 1st would change the laws, but he didn't. Catholics had to practise their religion in secret. There were even fines for people who didn't attend the Protestant church on Sunday or on holy days. James lst passed more laws against the Catholics when he became king. What happened - the Gunpowder Plot A group of men led by Robert Catesby, plotted to kill King James and blow up the Houses of Parliament, the place where the laws that governed England were made. Guy Fawkes was one of a group of men The plot was simple - the next time Parliament was opened by King James l, they would blow up everyone there with gunpowder. The men bought a house next door to the parliament building. The house had a cellar which went under the parliament building. They planned to put gunpowder under the house and blow up parliament and the king. -

Guided Cycle Ride

Cyclesolihull Routes Cyclesolihull Rides short route from Cycling is a great way to keep fit whilst at Cyclesolihull offers regular opportunities to S1 the same time getting from A to B or join with others to ride many of the routes in Dorridge exploring your local area. this series of leaflets. The rides are organised This series of routes, developed by by volunteers and typically attract between 10 and 20 riders. To get involved, just turn up and Cyclesolihull will take you along most of ride! the network of quiet lanes, roads and cycle paths in and around Solihull, introducing Sunday Cycle Rides take place most Cyclesolihull Sunday afternoons at 2 pm from April to you to some places you probably didn’t Explore your borough by bike even know existed! September and at 1.30 pm from October to March. One of the routes will be followed with a The routes have been carefully chosen to mixture of route lengths being ridden during avoid busier roads so are ideal for new each month. In autumn and winter there are cyclists and children learning to cycle on more shorter rides to reflect the reduced daylight hours. One Sunday each month in the road with their parents. spring and summer the ride is a 5 mile Taster You can cycle the routes alone, with family Ride. This is an opportunity to try a and friends, or join other people on one of Cyclesolihull ride without going very far and is the regular Cyclesolihull rides. an ideal introduction to the rides, especially for new cyclists and children. -

Gunpowder, Treason and Plot (Gunpowder Plot) Teacher Notes

Gunpowder, Treason and Plot (Gunpowder Plot) Teacher notes Duration: 45 minutes Meeting Point: Salt Tower Courtyard Why did the Gunpowder Plot fail? Explore the story of Guy Fawkes' plot to blow up the Houses of Parliament – and visit the prison cells that housed his fellow conspirators. Join a costumed presenter, portraying one of King James' courtiers, who will take you to a number of sites within the Tower that hold particular relevance for the plot of 1605. Learning objectives Children will: Learn key features of the Gunpowder Plot through questioning and participation. Compare and contrast life today with life in the 1600s. Develop historical enquiry skills and an understanding of chronology. National Curriculum links This session supports: Extending chronological knowledge of significant events in British history beyond 1066. Development of asking perceptive questions by exploring differing representations of a key historical figure. During your session: Please note that the 1:5 staff to child ratio which we ask for throughout your visit still applies during your learning session. We ask that sufficient adults remain with the group as they will be encouraged to join in with the session activities. For Health & Safety reason, our sessions are for a maximum of 35 children. The education session your group has booked with us takes place on the visitor route at the Tower of London. Please meet your session presenter at the Salt Tower Courtyard. This is marked on the map below with a star. The courtyard is located next to the New Armouries Cafe. This is the New Armouries Cafe This is the Salt Tower Courtyard Enter here This is where your costumed session presenter will meet you at your allocated start time. -

James I and Gunpowder Treason Day.', Historical Journal., 64 (2)

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 01 October 2020 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Williamson, P. and Mears, N. (2021) 'James I and Gunpowder treason day.', Historical journal., 64 (2). pp. 185-210. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X20000497 Publisher's copyright statement: This article has been published in a revised form in Historical Journal https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X20000497. This version is published under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND. No commercial re-distribution or re-use allowed. Derivative works cannot be distributed. c The Author(s) 2020. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk JAMES I AND GUNPOWDER TREASON DAY* PHILIP WILLIAMSON AND NATALIE MEARS University of Durham Abstract: The assumed source of the annual early-modern English commemoration of Gunpowder treason day on 5 November – and its modern legacy, ‘Guy Fawkes day’ or ‘Bonfire night’ – has been an act of parliament in 1606. -

Year 8 Independent Learning Booklet the Gunpowder Plot Name: History Teacher

Year 8 Independent Learning Booklet The Gunpowder Plot Name: History Teacher: 1 Task 1 – Use Source A and your own knowledge to describe how religion had changed under Tudor Monarchs. Source A Source A shows_______________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ 2 ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________ Task 2 Using the knowledge organiser and, if you can, additional research, describe what the Catholics hoped would happen when James I came to power and what James I actually did and why. Catholic hope after when James I How Catholics were -

Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot

Maestralidia.com Guy Fawkes and the gunpowder plot Why do we learn about Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot? In England, in 1605 during the reign of James I, an act of treason was planned. At the last moment, the Gunpowder Plot fails, and now we commemorate the traitors - and in particular Guy Fawkes - every year with Bonfire Night! Who is Guy Fawkes? Guy Fawkes (1570 to 1606), also known as Guido Fawkes, is one of a group of Catholic plotters who plans to blow up the Parliament - now known as the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. What is the Gunpowder Plot? At the time, King James I is on the throne. England had broken away from the Catholic faith and the Church of Rome in Henry VIII's reign (by 1536), but there are still many Catholics in the country. Guy Fawkes, with a group of thirteen Catholic plotters, plans to overthrow the King and put a Catholic monarch back on the throne. The plotters put barrels of gunpowder in the cellars of the Parliament. They plan to set of the gunpowder during the opening of Parliament, on 5th November 1605. One or more of the plotters, however, are worried that some of their fellow Catholics and friends would be at the opening. A certain Lord Monteagle receives a letter warning him don’t go to the Parliament because of the danger. Lord Monteagle shows the letter to the King, and the cellars are thoroughly searched and Guy Fawkes caught. After several days of horrible torture, Guy Fawkes gives up the names of his plotters and all are found guilty and executed. -

The Gunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder Plot Teacher Resource Pack In this Resource Pack you will find: 1. The Journey to 1605 3. Pre-Visit Classroom Activities 4. Post-Visit Activity Starters (Cross-Curricular) An illustrated timeline highlighting key figures i. What do we know about the Tower of London? connected to the Tower of London and the An activity to introduce the Tower of London Ideas to extend children’s learning Gunpowder Plot, including things to look to the class, with the opportunity for children back in the classroom. out for on the day of your visit. to share their knowledge. A follow-up post-visit activity is also included: What did we find out 5. Useful Links 2. Setting the Scene: about the Tower of London? A selection of web links providing i. The Tower of London: Palace, Prison, Fortress ii. Playing by the Rules further information and ideas. ii. Religion and Monarchy in the lead up to 1605 A two-part activity to help children gain an A concise introduction to the Tower of London understanding of why the Gunpowder Plot and the key themes surrounding the Gunpowder happened. Plot. This background information will help you Part One uses the context of sport to get prepare your class for their visit and support you children thinking about what is important to in delivering our proposed pre-visit activities. them and how it would feel to be deprived of it. Part Two aims to link the children’s discoveries from Part One to the religious context in which the Gunpowder Plot took place. -

KS2 Gunpowder Treason & Plot Timeline

Gunpowder Treason & Plot: Timeline Factsheet 1564-1616 William Shakespeare’s lifetime 24 March 1603 Queen Elizabeth I dies and James I takes over the throne. 1604 The Plot takes shape 20 May Robert Catesby, Thomas Winter, Jack Wright, Thomas Percy and Guy Fawkes meet in a London pub called the Duck and Drake. Catesby reveals his plan to blow up Parliament. 24 May Thomas Percy rents a small house next to the Lords’ Chamber. December The plotters start digging their tunnel under the wall of the House of Lords. 1605 The Gunpowder Plot fails March The plotters rent a storeroom under the House of Lords and begin to smuggle in barrels of gunpowder. 26 October Lord Monteagle receives the mysterious letter warning him of the evil plan. 4 November King James orders a search of the Houses of Parliament. Guy Fawkes is found in the storeroom with the gunpowder and is arrested. 5 November The rest of the plotters leave London, most of them headed for the Midlands. 7 November Fawkes makes his first confession in the Tower of London. 8 November Catesby, Percy and the Wright brothers are killed in a shoot-out at Holbeach House. 9 November King James makes a speech about the Plot at the Opening of Parliament. 1606 Trials and executions 27 January Digby, Grant, Fawkes, Keyes, Rookwood, the Winters and Bates go on trial at Westminster Hall. 30 January Digby, Robert Winter, Grant and Bates are executed in St Paul’s Churchyard. 31 January Fawkes, Rookwood, Thomas Winter and Keyes are executed in Old Palace Yard, Westminster. -

Rastrick High School Year 8 History History Home Learning: 17Th Century England Information Booklet

Rastrick High School Year 8 History History Home Learning: 17th Century England Information Booklet Y8 History Home Learning: How Bloody and Brutal was 17th Century England? Information booklet Lesson Two: Were witches real? Witches in the 1600s were believed to be usually old poor women with: • birth marks, pocs or warts on their face • Sunken faces with hairy lips • and familiars. Familiars were demons that followed witches that were believed to assume the form of animals, usually cats. These ideas that we hold about what witches look like are stereotypical. Stereotype means an oversimplified image of a person or thing that are usually wrong. In 1597 James I produced a book on witchcraft entitled ‘Daemononlogie’. In the book he explained how to ‘spot’ a witch simply by looking for the previous signs. He also said a witch could be spotted: 1. If they are a friend, neighbour or relative of a witch. 2. If a person dies or has an accident after arguing with the accused. 3. If everybody who lives near the person believes that they are a witch. Why did people believe in witches? Lesson Three: Were witches real? Who was Matthew Hopkins? A bloodthirsty Altofts man was responsible for the deaths of more than 300 women - according to an old legend. Nearly 350 years ago self-styled ‘Witch-finder General’ Matthew Hopkins roamed the counties of eastern England preying on elderly women. His reign of terror began in 1644 when he was employed by towns to seek out and destroy women believed to be witches. Such has been the interest in Matthew Hopkins’ crimes that in 1968 Vincent Price starred in a horror film called The Witch- finder General. -

This Is a Repository Copy of Ben Jonson and Religion

This is a repository copy of Ben Jonson and Religion. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/120396/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Searle, A orcid.org/0000-0002-9672-6353 (2015) Ben Jonson and Religion. In: Giddens, E, (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Ben Jonson. Oxford University Press , Oxford, UK . ISBN 9780199544561 https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199544561.013.29 © Oxford University Press, 2014. This is an author produced version of a paper published in The Oxford Handbook of Ben Jonson. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Alison Searle – Ben Jonson and Religion This is an author’s copy.