Vertical Administration, Information Flow and Governance Dilemma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.21 Zhejiang Province Zhejiang Donglian Group Co., Ltd.,1 Affiliated

2.21 Zhejiang Province Zhejiang Donglian Group Co., Ltd.,1 affiliated to Zhejiang Provincial Prison Administration Bureau, has 17 prison enterprises Legal representative of the prison company: Hu Fangrui, Chairman of Zhejiang Donglian Group Co., Ltd His official positions in the prison system: Director of Zhejiang Provincial Prison Administration Bureau2 No. Company Name of the Legal Person Legal Registered Business Scope Company Notes on the Prison Name Prison, to and representative/Title Capital Address which the Shareholder(s) Company Belongs 1 Zhejiang Zhejiang Zhejiang Hu Fangrui 11.95 million Capital management; industrial 15th – 17th Zhejiang Provincial Prison Administration Donglian Group Provincial Provincial Chairman of Zhejiang yuan investment and development; Floors, No. Bureau is a deputy department-level Co., Ltd. Prison Government Donglian Group Co., production, processing and sale 276 Jianguo administrative agency, which is in charge of Administration Ltd; Director of of electromechanical equipment, North Road, implementing penalties and running prison Bureau Zhejiang Provincial hardware and electrical Hangzhou City enterprises. It is under the jurisdiction of Prison Administration equipment, chemical raw the Provincial Department of Justice. Bureau3 materials and products Address: 110 Tianmushan Road, Hangzhou (excluding dangerous goods and City. precursor chemicals), metallic The bureau assigns responsibilities of materials, decorative building production, operation and management to materials, daily necessities and -

Asian Journal of Chemistry Asian Journal of Chemistry

Asian Journal of Chemistry; Vol. 27, No. 5 (2015), 1913-1915 ASIAN JOURNAL OF CHEMISTRY http://dx.doi.org/10.14233/ajchem.2015.18513 Simultaneous Determination of Four Active Flavonoids in Citrus Changshan Huyou Fruit Collected in Various Seasons by HPLC Method 1,† 2,†,* 3 1 4 JIAN-FENG SONG , JING-QIAN FENG , JIAN-HUA HU , LI-PING XU and HOU-DAO FU 1Quzhou Institute for Food and Drug Control, No. 109, Heer Road, Kecheng Dist., Quzhou 324000, Zhejiang Province, P.R. China 2Quzhou College of Technology, No. 18, Jiangyuan Road, Kecheng Dist., Quzhou 324000, Zhejiang Province, P.R. China 3Quzhou NanKong Chinese medicine Co., Ltd, No. 11, Chunyuan Zhong Road, Qujiang Dist., Quzhou 324000, Zhejiang Province, P.R. China 4Second People's Hospital of Ningbo, No. 41, Xibei Road, Haishu Dist., Ningbo 315010, Zhejiang Province, P.R. China *Corresponding author: Tel: +86 570 8068339; E-mail: [email protected] †Contribute equally to this work and should be considered as co-first author Received: 25 July 2014; Accepted: 30 November 2014; Published online: 20 February 2015; AJC-16920 An HPLC method was developed for the simultaneous determination of narirutin, naringin, hesperidin and neohesperidin to investigate active ingredients in citrus Changshan Huyou fruit collected in different harvest time. The solid phase was Agilent ZORBAX SB-C18 (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm), with isocratic elution using 0.2 % phosphoric acid solution-acetonitrile (85:15) as the mobile phase. The flow rate was 1 mL/min and the wavelength was 284 nm. The methodology all fit the analytical requests and the recoveries were 98.83-99.05 %. -

Rhinogobius Immaculatus, a New Species of Freshwater Goby (Teleostei: Gobiidae) from the Qiantang River, China

ZOOLOGICAL RESEARCH Rhinogobius immaculatus, a new species of freshwater goby (Teleostei: Gobiidae) from the Qiantang River, China Fan Li1,2,*, Shan Li3, Jia-Kuan Chen1 1 Institute of Biodiversity Science, Ministry of Education Key Laboratory for Biodiversity Science and Ecological Engineering, Fudan University, Shanghai 200433, China 2 Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai 200090, China 3 Shanghai Natural History Museum, Branch of Shanghai Science & Technology Museum, Shanghai 200041, China ABSTRACT non-diadromous (landlocked) (Chen et al., 1999a, 2002; Chen A new freshwater goby, Rhinogobius immaculatus sp. & Kottelat, 2005; Chen & Miller, 2014; Huang & Chen, 2007; Li & Zhong, 2009). nov., is described here from the Qiantang River in In total, 44 species of Rhinogobius have been recorded in China. It is distinguished from all congeners by the China (Chen et al., 2008; Chen & Miller, 2014; Huang et al., following combination of characters: second dorsal-fin 2016; Huang & Chen, 2007; Li et al., 2007; Li & Zhong, 2007, rays I, 7–9; anal-fin rays I, 6–8; pectoral-fin rays 2009; Wu & Zhong, 2008; Yang et al., 2008), eight of which 14–15; longitudinal scales 29–31; transverse scales have been reported from the Qiantang River basin originating 7–9; predorsal scales 2–5; vertebrae 27 (rarely 28); in southeastern Anhui Province to eastern Zhejiang Province. These species include R. aporus (Zhong & Wu, 1998), R. davidi preopercular canal absent or with two pores; a red (Sauvage & de Thiersant, 1874), R. cliffordpopei (Nichols, oblique stripe below eye in males; branchiostegal 1925), R. leavelli (Herre, 1935a), R. lentiginis (Wu & Zheng, membrane mostly reddish-orange, with 3–6 irregular 1985), R. -

Factory Address Country

Factory Address Country Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

China Zheshang Bank Co., Ltd. 浙 商 銀 行 股 份 有 限

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. CHINA ZHESHANG BANK CO., LTD. 浙商銀行股份有限公司* (A joint-stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 2016) 2016 INTERIM RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT The board of directors of China Zheshang Bank Co., Ltd. (the “Bank”) hereby announces the unaudited results of the Bank for the six months ended June 30, 2016. This announcement, containing the full text of the 2016 interim report of the Bank, complies with the relevant requirements of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “Stock Exchange”) in relation to information to accompany preliminary announcements of interim results. Publication of Interim Results Announcement and Interim Report Both the Chinese and English versions of this results announcement are available on the websites of the Bank (www.czbank.com) and the Stock Exchange (www.hkex.com.hk). In the event of any discrepancies in interpretations between the English and Chinese text, the Chinese version shall prevail. Printed version of the 2016 interim report of the Bank will in due course be delivered to the H Share holders of the Bank and available for viewing on the websites of the Bank (www.czbank.com) and the Stock Exchange (www.hkex.com.hk). -

Supplementary Materials for the Article: a Running Start Or a Clean Slate

Supplementary Materials for the article: A running start or a clean slate? How a history of cooperation affects the ability of cities to cooperate on environmental governance Rui Mu1, * and Wouter Spekkink2 1 Dalian University of Technology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences; [email protected] 2 The University of Manchester, Sustainable Consumption Institute; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-139-0411-9150 Appendix 1: Environmental Governance Actions in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Urban Agglomeration Event time Preorder Action Event Event name and description Actors involved (year-month-day) event no. type no. Part A: Joint actions at the agglomeration level MOEP NDRC Action plan for Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei and the surrounding areas to implement MOIIT 2013 9 17 FJA R1 air pollution control MOF MOHURD NEA BG TG HP MOEP NDRC Collaboration mechanism of air pollution control in Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei and 2013 10 23 R1 FJA MOIIT R2 the surrounding areas MOF MOHURD CMA NEA MOT BG Coordination office of air pollution control in Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei and the 2013 10 23 R2 FJA TG R3 surrounding areas HP 1 MOEP NDRC MOIIT MOF MOHURD CMA NEA MOT BG Clean Production Improvement Plan for Key Industrial Enterprises in Beijing, TG 2014 1 9 R1 FJA R4 Tianjin, Hebei and the Surrounding Areas HP MOIIT MOEP BTHAPCLG Regional air pollution joint prevention and control forum (the first meeting) 2014 3 3 R2, R3 IJA BEPA R5 was held by the Coordination Office. TEPA HEPA Coordination working unit was established for comprehensive atmospheric BTHAPCLG 2014 3 25 R3 FJA R6 pollution control. -

Space As Sociocultural Construct: Reinterpreting the Traditional Residences in Jinqu Basin, China from the Perspective of Space Syntax

sustainability Article Space as Sociocultural Construct: Reinterpreting the Traditional Residences in Jinqu Basin, China from the Perspective of Space Syntax Yu Chen 1,2,†, Keyou Xu 1,†, Pei Liu 1, Ruyu Jiang 1, Jingyi Qiu 1, Kangle Ding 3,* and Hiroatsu Fukuda 2,* 1 College of Landscape and Architecture, Zhejiang A&F University, Hangzhou 311300, China; [email protected] (Y.C.); [email protected] (K.X.); [email protected] (P.L.); [email protected] (R.J.); [email protected] (J.Q.) 2 Faculty of Environmental Engineering, The University of Kitakyushu, Kitakyushu 808-0135, Japan 3 School of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Zhejiang University of Science and Technology, Hangzhou 310023, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (K.D.); [email protected] (H.F.) † These authors contributed equally to the study. Abstract: The traditional residence with protogenetic spatial arrangement is regarded as a critical carrier of social logic of space, which makes it an ideal object for studying the relationship between the spatial form and social context. To this end, a comparative analysis is conducted using Depthmap Software. This study is based on space syntax theory between two groups of proxies of sharp differences in spatial organization in one geomorphic unit where the natural factors show little variations, while the human factors present a bifurcating distribution. Furthermore, the study clarifies the differences among genotypes of the domestic space system. Finally, combined with Citation: Chen, Y.; Xu, K.; Liu, P.; historical material, it proves the dual division of regional sociocultural factors as decisive forces Jiang, R.; Qiu, J.; Ding, K.; Fukuda, H. -

356-У От 15.03.2010. Китай, Списки По Кормам Утв. 15.03.2010

ФЕДЕРАЛЬНАЯ СЛУЖБА ПО ВЕТЕРИНАРНОМУ И Руководителям территориальных ФИТОСАНИТАРНОМУ управлений Россельхознадзора НАДЗОРУ (по списку) (Россельхознадзор) Управление ветеринарного надзора Орликов пер., 1/11, Москва, 107139 Д ля телеграмм: Москва 84 Минроссельхоз тел/факс: (499) 975-58-50 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.fsvps.ru 15.03.10 № 2-04/356 На № ____________________________ Федеральная служба по ветеринарному и фитосанитарному надзору направляет утвержденный 15 марта 2010 года список предприятий Китайской Народной Республики, имеющих право на экспорт кормов и кормовых добавок для животных в Российскую Федерацию. Настоящую информацию доведите до сведения органов управления ветеринарией субъектов Российской Федерации, а также заинтересованных организаций. Приложение: на 7 листах. Начальник подпись С.В. Захаров Корягин (499) 975-59-29 Утверждаю Заместитель Руководителя Федеральной службы по ветеринарному и фитосанитарному надзору подпись Н.А. Власов « 15 » марта 2010 г. Список предприятий Китайской Народной Республики, имеющих право на экспорт кормов и кормовых добавок для животных в Российскую Федерацию Регистрационный № Аттестованный вид номер Название предприятия Адрес предприятия Провинция п/п деятельности предприятия 浙江省平阳县水头镇206号蒲 潭村水 南路NO. 平阳县孔迎宠物用品 PINGYA有NG限公司 206 SHUINAN ROAD PUTAN VILLAGE SHUITOU ZHEJIANG Корма для кошек и 1 3300PF001 KONGYING PET PRODUCTS TOWN PINGYANG COUNTY WENZHOU CITY ЧЖЭЦЗЯН собак CO.,LTD. ZHEJIANG PROVINCE CHINA 浙江省平阳县萧江镇工 业园区 岱 口段DAIKOU 温州锦恒宠物 用品有 WENZH限OU公司 ZHEJIANG Корма для кошек и 2 3300PF003 SECTION INDUSTRIAL PARK XIAOJIANG TOWN JINHENG PET PRODUCTS CO.,LTD. ЧЖЭЦЗЯН собак PINGYANG ZHEJIANG CHINA 平阳县宠物玩 具实业 ZHEJ公司IANG 平阳县水头镇 寺前村 ZHEJIANG Корма для кошек и 3 3300PF004 PINGYANG PET-TOYS INDUSTRIAL SIQIAN VILLAGE SHUITOU TOWN PINGYANG ЧЖЭЦЗЯН собак CO. COUNTY ZHEJIANG PROVINCE CHINA 浙江省平阳县水头镇金1号山洋工 业区 NO.1 温州锦华宠物 用品有 WENZH限OU公司 ZHEJIANG Корма для кошек и 4 3300PF005 JINGSHAN INDUSTRIAL AREA SHUITOU TOWN JINHUA PET PRODUCTS CO.,LTD. -

Sustainable Development of New Urbanization from the Perspective of Coordination: a New Complex System of Urbanization-Technology Innovation and the Atmospheric Environment

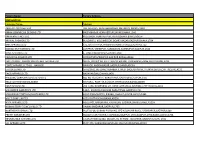

atmosphere Article Sustainable Development of New Urbanization from the Perspective of Coordination: A New Complex System of Urbanization-Technology Innovation and the Atmospheric Environment Bin Jiang 1, Lei Ding 1,2,* and Xuejuan Fang 3 1 School of International Business & Languages, Ningbo Polytechnic, Ningbo 315800, Zhejiang, China; [email protected] 2 Institute of Environmental Economics Research, Ningbo Polytechnic, Ningbo 315800, Zhejiang, China 3 Ningbo Institute of Oceanography, Ningbo 315832, Zhejiang, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 26 September 2019; Accepted: 25 October 2019; Published: 28 October 2019 Abstract: Exploring the coordinated development of urbanization (U), technology innovation (T), and the atmospheric environment (A) is an important way to realize the sustainable development of new-type urbanization in China. Compared with existing research, we developed an integrated index system that accurately represents the overall effect of the three subsystems of UTA, and a new weight determination method, the structure entropy weight (SEW), was introduced. Then, we constructed a coordinated development index (CDI) of UTA to measure the level of sustainability of new-type urbanization. This study also analyzed trends observed in UTA for 11 cities in Zhejiang Province of China, using statistical panel data collected from 2006 to 2017. The results showed that: (1) urbanization efficiency, the benefits of technological innovation, and air quality weigh the most in the indicator systems, which indicates that they are key factors in the behavior of UTA. The subsystem scores of the 11 cities show regional differences to some extent. (2) Comparing the coordination level of UTA subsystems, we found that the order is: coordination degree of UT > coordination degree of UA > coordination degree of TA. -

Factory Name

Factory Name Factory Address BANGLADESH Company Name Address AKH ECO APPARELS LTD 495, BALITHA, SHAH BELISHWER, DHAMRAI, DHAKA-1800 AMAN GRAPHICS & DESIGNS LTD NAZIMNAGAR HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,1340 AMAN KNITTINGS LTD KULASHUR, HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH ARRIVAL FASHION LTD BUILDING 1, KOLOMESSOR, BOARD BAZAR,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,1704 BHIS APPARELS LTD 671, DATTA PARA, HOSSAIN MARKET,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1712 BONIAN KNIT FASHION LTD LATIFPUR, SHREEPUR, SARDAGONI,KASHIMPUR,GAZIPUR,1346 BOVS APPARELS LTD BORKAN,1, JAMUR MONIPURMUCHIPARA,DHAKA,1340 HOTAPARA, MIRZAPUR UNION, PS : CASSIOPEA FASHION LTD JOYDEVPUR,MIRZAPUR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH CHITTAGONG FASHION SPECIALISED TEXTILES LTD NO 26, ROAD # 04, CHITTAGONG EXPORT PROCESSING ZONE,CHITTAGONG,4223 CORTZ APPARELS LTD (1) - NAWJOR NAWJOR, KADDA BAZAR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH ETTADE JEANS LTD A-127-131,135-138,142-145,B-501-503,1670/2091, BUILDING NUMBER 3, WEST BSCIC SHOLASHAHAR, HOSIERY IND. ATURAR ESTATE, DEPOT,CHITTAGONG,4211 SHASAN,FATULLAH, FAKIR APPARELS LTD NARAYANGANJ,DHAKA,1400 HAESONG CORPORATION LTD. UNIT-2 NO, NO HIZAL HATI, BAROI PARA, KALIAKOIR,GAZIPUR,1705 HELA CLOTHING BANGLADESH SECTOR:1, PLOT: 53,54,66,67,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH KDS FASHION LTD 253 / 254, NASIRABAD I/A, AMIN JUTE MILLS, BAYEZID, CHITTAGONG,4211 MAJUMDER GARMENTS LTD. 113/1, MUDAFA PASCHIM PARA,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1711 MILLENNIUM TEXTILES (SOUTHERN) LTD PLOTBARA #RANGAMATIA, 29-32, SECTOR ZIRABO, # 3, EXPORT ASHULIA,SAVAR,DHAKA,1341 PROCESSING ZONE, CHITTAGONG- MULTI SHAF LIMITED 4223,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH NAFA APPARELS LTD HIJOLHATI, -

Regeneration of Plants from Ancestry Tree of Citrus Changshan-Huyou Y. B. Chang Via Tissue Culture

Bangladesh J. Bot. 46(3): 1233-1240, 2017 (September) Supplementary REGENERATION OF PLANTS FROM ANCESTRY TREE OF CITRUS CHANGSHAN-HUYOU Y. B. CHANG VIA TISSUE CULTURE YAFEI LI, SHIYI ZHOU, MI FENG, YOUHE LIN, LINJIE LI, 1 GAOSAI MA AND TAIHE XIANG* College of Life and Environment Sciences, Hangzhou Normal University, Hangzhou 310036, China Keywords: Citrus changshan-huyou, Ancestry tree, Tissue culture, Regenerated plant Abstract Tissue culture with young leaves, stems, and embryos of the commonly grown cultivars of Citrus changshan-huyou Y. B. Chang was carried out. The results indicated that the young embryo of C. changshan- huyou cultivars was the best explant for regeneration of plants via tissue culture. Based on this result, young fruit of “Ancestry Tree” of Citrus changshan-huyou was selected. After being stored at 4oC for 6 days, the embryos were cultured on MS medium containing 0.5 mg/l BA + 0.5 mg/l NAA to induce the formation of callus. The induced callus were cultured on MS medium containing 1 mg/l BA and induced to differentiate into cluster buds, which were cut and cultured on MS medium containing 0.4 mg/l IAA to induce the formation of roots. Finally, a technological system for regeneration of plants from the “Ancestry Tree” of C. changshan-huyou via tissue culture was successfully established. This study has paved the foundation for protection and further utilization of “Ancestry Tree” of C. changshan-huyou, the precious and rare germplasm resource. Introduction Citrus changshan-huyou Y. B. Chang (Fam.: Rutaceae) was originally generated in Changshan County in Zhejiang Province, China. -

The Order of Local Things: Popular Politics and Religion in Modern

The Order of Local Things: Popular Politics and Religion in Modern Wenzhou, 1840-1940 By Shih-Chieh Lo B.A., National Chung Cheng University, 1997 M.A., National Tsing Hua University, 2000 A.M., Brown University, 2005 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND May 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Shih-Chieh Lo ii This dissertation by Shih-Chieh Lo is accepted in its present form by the Department of History as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date_____________ ________________________ Mark Swislocki, Advisor Recommendation to the Graduate Council Date_____________ __________________________ Michael Szonyi, Reader Date_____________ __________________________ Mark Swislocki, Reader Date_____________ __________________________ Richard Davis, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date______________ ___________________________ Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School iii Roger, Shih-Chieh Lo (C. J. Low) Date of Birth : August 15, 1974 Place of Birth : Taichung County, Taiwan Education Brown University- Providence, Rhode Island Ph. D in History (May 2010) Brown University - Providence, Rhode Island A. M., History (May 2005) National Tsing Hua University- Hsinchu, Taiwan Master of Arts (June 2000) National Chung-Cheng University - Chaiyi, Taiwan Bachelor of Arts (June 1997) Publications: “地方神明如何平定叛亂:楊府君與溫州地方政治 (1830-1860).” (How a local deity pacified Rebellion: Yangfu Jun and Wenzhou local politics, 1830-1860) Journal of Wenzhou University. Social Sciences 溫州大學學報 社會科學版, Vol. 23, No.2 (March, 2010): 1-13. “ 略論清同治年間台灣戴潮春案與天地會之關係 Was the Dai Chaochun Incident a Triad Rebellion?” Journal of Chinese Ritual, Theatre and Folklore 民俗曲藝 Vol. 138 (December, 2002): 279-303. “ 試探清代台灣的地方精英與地方社會: 以同治年間的戴潮春案為討論中心 Preliminary Understandings of Local Elites and Local Society in Qing Taiwan: A Case Study of the Dai Chaochun Rebellion”.