Experiences of Community Leaders Following an Enhanced Fujita 5 Tornado Thomas Edward Orr Walden University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developing a Tornado Emergency Plan for Schools in Michigan

A GUIDE TO DEVELOPING A TORNADO EMERGENCY PLAN FOR SCHOOLS Also includes information for Instruction of Tornado Safety The Michigan Committee for Severe Weather Awareness March 1999 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS: A GUIDE TO DEVELOPING A TORNADO EMERGENCY PLAN FOR SCHOOLS IN MICHIGAN I. INTRODUCTION. A. Purpose of Guide. B. Who will Develop Your Plan? II. Understanding the Danger: Why an Emergency Plan is Needed. A. Tornadoes. B. Conclusions. III. Designing Your Plan. A. How to Receive Emergency Weather Information B. How will the School Administration Alert Teachers and Students to Take Action? C. Tornado and High Wind Safety Zones in Your School. D. When to Activate Your Plan and When it is Safe to Return to Normal Activities. E. When to Hold Departure of School Buses. F. School Bus Actions. G. Safety during Athletic Events H. Need for Periodic Drills and Tornado Safety Instruction. IV. Tornado Spotting. A. Some Basic Tornado Spotting Techniques. APPENDICES - Reference Materials. A. National Weather Service Products (What to listen for). B. Glossary of Weather Terms. C. General Tornado Safety. D. NWS Contacts and NOAA Weather Radio Coverage and Frequencies. E. State Emergency Management Contact for Michigan F. The Michigan Committee for Severe Weather Awareness Members G. Tornado Safety Checklist. H. Acknowledgments 2 I. INTRODUCTION A. Purpose of guide The purpose of this guide is to help school administrators and teachers design a tornado emergency plan for their school. While not every possible situation is covered by the guide, it will provide enough information to serve as a starting point and a general outline of actions to take. -

Tornadoes & Funnel Clouds Fake Tornado

NOAA’s National Weather Service Basic Concepts of Severe Storm Spotting 2009 – Rusty Kapela Milwaukee/Sullivan weather.gov/milwaukee Housekeeping Duties • How many new spotters? - if this is your first spotter class & you intend to be a spotter – please raise your hands. • A basic spotter class slide set & an advanced spotter slide set can be found on the Storm Spotter Page on the Milwaukee/Sullivan web site (handout). • Utilize search engines and You Tube to find storm videos and other material. Class Agenda • 1) Why we are here • 2) National Weather Service Structure & Role • 3) Role of Spotters • 4) Types of reports needed from spotters • 5) Thunderstorm structure • 6) Shelf clouds & rotating wall clouds • 7) You earn your “Learner’s Permit” Thunderstorm Structure Those two cloud features you were wondering about… Storm Movement Shelf Cloud Rotating Wall Cloud Rain, Hail, Downburst winds Tornadoes & Funnel Clouds Fake Tornado It’s not rotating & no damage! Let’s Get Started! Video Why are we here? Parsons Manufacturing 120-140 employees inside July 13, 2004 Roanoke, IL Storm shelters F4 Tornado – no injuries or deaths. They have trained spotters with 2-way radios Why Are We Here? National Weather Service’s role – Issue warnings & provide training Spotter’s role – Provide ground-truth reports and observations We need (more) spotters!! National Weather Service Structure & Role • Federal Government • Department of Commerce • National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration • National Weather Service 122 Field Offices, 6 Regional, 13 River Forecast Centers, Headquarters, other specialty centers Mission – issue forecasts and warnings to minimize the loss of life & property National Weather Service Forecast Office - Milwaukee/Sullivan Watch/Warning responsibility for 20 counties in southeast and south- central Wisconsin. -

Preparedness and Partnerships: Lessons Learned from the Missouri Disasters of 2011 a Focus on Joplin

Preparedness and Partnerships: LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE MISSOURI DISASTERS OF 2011 A Focus on Joplin Coordination Incident Command Documentation Communication ESS RES DN PO RE N A S P E E R P R E N C O O I V T E A R G I Y T I M x Preparedness and Partnerships: LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE MISSOURI DISASTERS OF 2011 A Focus on Joplin TABLE OF CONTENTS E xecutive Summary _________________________________________________________ 2 The Missouri Hospital Association as a Response Organization ____________________ 8 Lessons Learned ___________________________________________________________ 10 Planning ______________________________________________________11 Communication _______________________________________________ 21 Resources and Assets __________________________________________ 24 Safety and Security ____________________________________________ 26 Staffing Responsibilities _________________________________________ 29 Staffing ________________________________________________ 29 Volunteers ______________________________________________ 31 Utilities Management __________________________________________ 32 Patient, Clinical and Support Activities ____________________________ 33 Medical Surge ___________________________________________ 33 References and Acknowledgements ___________________________________________ 36 Disclaimer: This report reflects information gathered from many hospital staff through surveys, interviews, presentations and individual and group discussions. The information relates individual and organization-specific identified -

2013 Tornado and Severe Weather Awareness Drill

2013 Tornado and Severe Weather Awareness Drill Scheduled for Thursday April 18, 2013 The 2013 Tornado Drill will consist of a mock tornado watch and a mock tornado warning for all of Wisconsin. This is a great opportunity for your school, business and community to practice your emergency plans. DRILL SCHEDULE: 1:00 p.m. – National Weather Service issues a mock tornado watch for all of Wisconsin (a watch means tornadoes are possible in your area. Remain alert for approaching storms). 1:45 p.m. - National Weather Service issues mock tornado warning for all of Wisconsin (a warning means a tornado has been sighted or indicated on weather radar. Move to a safe place immediately). 2:00 p.m. – End of mock tornado watch/warning drill The tornado drill will take place even if the sky is cloudy, dark and/or rainy. If actual severe storms are expected in the state on Thursday, April 18, the tornado drill will be postponed until Friday, April 19 with the same times. If severe storms are possible Friday, the drill will be cancelled. Information on the status of the drill will be posted at ReadyWisconsin.wi.gov. Most local and state radio, TV and cable stations will be participating in the drill. Television viewers and radio station listeners will hear a message at 1:45 p.m. indicating that “This is a test.” The mock tornado warning will last about one minute on radio and TV stations across Wisconsin and when the test is finished, stations will return to normal programming. In addition, alerts for both the mock tornado watch and warning will be issued over NOAA weather radios. -

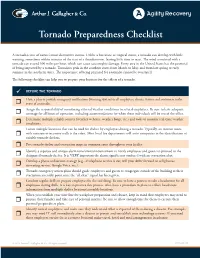

Tornado Preparedness Checklist

Tornado Preparedness Checklist A tornado is one of nature’s most destructive storms. Unlike a hurricane or tropical storm, a tornado can develop with little warning, sometimes within minutes of the start of a thunderstorm, leaving little time to react. "e wind associated with a tornado can exceed 300 miles per hour, which can cause catastrophic damage. Every area in the United States has the potential of being impacted by a tornado. Tornadoes peak in the southern states from March to May, and from late spring to early summer in the northern states. "e importance of being prepared for a tornado cannot be overstated. "e following checklist can help you to prepare your business for the e#ects of a tornado. 9 BEFORE THE TORNADO Have a plan to provide emergency noti$cations (warning system) to all employees, clients, visitors and customers in the event of a tornado. Assign the responsibility of monitoring external weather conditions to several employees. Be sure to have adequate coverage for all hours of operation, including accommodations for when these individuals will be out of the o%ce. Determine multiple reliable sources (weather websites, weather blogs, etc.) and tools to monitor real-time weather conditions. Locate multiple locations that can be used for shelter by employees during a tornado. Typically, an interior room with concrete or masonry walls is the safest. Most local $re departments will assist companies in the identi$cation of suitable tornado shelters. Post tornado shelter and evacuation maps in common areas throughout your facility. Identify a separate and unique alarm tone/siren/announcement to notify employees and guests to proceed to the designated tornado shelter. -

Human Vulnerability to Tornadoes in the United States Is Highest In

1 Human vulnerability to tornadoes in the United States is highest in 2 urbanized areas of the Mid South ∗ 3 James B. Elsner and Tyler Fricker 4 Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida ∗ 5 Corresponding author address: James B. Elsner, Department of Geography, Florida State Univer- 6 sity, 113 Collegiate Loop, Tallahassee, FL 32301. 7 E-mail: [email protected] Generated using v4.3.2 of the AMS LATEX template 1 ABSTRACT 8 Risk factors for tornado casualties are well known. Less understood is how 9 and to what degree these factors, after controlling for strength and the number 10 of people affected, vary over space and time. Here we fit models to casualty 11 counts from all casualty-producing tornadoes during the period 1995–2016 in 12 order to quantify the interactions between population and energy on casualty 13 (deaths plus injuries) rates. Results show that the more populated areas of the 14 Mid South are substantially and significantly more vulnerable to casualties 15 than elsewhere in the country. In this region casualty rates are significantly 16 higher on the weekend. Night and day casualty rates are similar regardless 17 of where the tornadoes occur. States with a high percentage of older people 18 (65+) tend to have greater vulnerability perhaps related to less agility and 19 fewer communication options. 2 20 1. Introduction 21 Nearly one fifth of all natural-hazards fatalities in the United States are the direct result of tor- 22 nadoes (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 2015). A tornado that hits a city is 23 capable of inflicting hundreds or thousands of casualties. -

City of Kenner Emergency Operations Plan (COKEOP), Augmenting the Basic Plan (BP)

CITY OF KENNER EMERGENCY OPERATIONS PLAN Annex “A” HURRICANE AND STORM PLAN (H&SP) Issued: June 1, 2007 Revised: November 1, 2011 City of Kenner, Louisiana Hurricane and Storm Plan June 1, 2007 I. PURPOSE The purpose of the City of Kenner Hurricane & Storm Plan (hereafter referred to as “Plan” or “H&SP”) is to describe the emergency response of City agencies in the event of a hurricane or severe storm. This document is intended to serve as a guide for the delivery and coordination of governmental services prior to, during, and following a storm incident. The guidelines set forth will facilitate the City’s Emergency Planning Advisory Group (EPAG) and executive’s decision-making regarding preparation, response and management of storm incidents. II. SCOPE This Plan is an administrative directive governing the operations of the City of Kenner, its subordinate agencies and departments. This document in no way purports to cover all aspects of storm related disaster/emergency or recovery management. Rather, it is intended to provide City personnel with an outline of those essential functions and duties to be performed in the event of a hurricane or storm event. - 1 - Revised: November 1, 2011 City of Kenner, Louisiana Hurricane and Storm Plan June 1, 2007 TITLE I. PLAN IMPLEMENTATION III. HURRICANE AND STORM PLAN IMPLEMENTATION The City of Kenner Hurricane and Storm Plan (H&SP) is a component of the City of Kenner Emergency Operations Plan (COKEOP), augmenting the Basic Plan (BP). Upon learning or receiving information from any source of a developing, pending, or actual hurricane or storm event, the Mayor or his/her designee may implement all or any portion of the COKEOP-BP or H&SP. -

RTAP Fact Sheet

Spring 2009 Kansas RTAP Fact Sheet A Service of The University of Kansas Transportation Center for Rural Transit Providers New Preparedness Guide by Kelly Heavey tied down. On the road, a bus driver should have discussed the weather conditions with a supervisor prior to beginning a shift. Open communication should be maintained, especially if the weather worsens. A bus should not accept riders if there is a tornado warning in effect, said Iowa’s State Transportation Director Terry Voy, cited in a North Carolina School Bus Safety’s Web site resource called Tornado Preparedness. If a tornado touches down en route, Voy says the driver should be aware of any possible shelters on the route, such as buildings, caves or any other strong ansas is smack-dab in the conditions outside. Be aware of the structure to protect people. Do not take middle of tornado alley, due to alerts that may occur around you, such shelter under an overpass. Kthe collision of winds from the as sirens or radio broadcasts. If a shelter cannot be found, the arctic North and from the balmy Gulf In the office, designate a shelter in rider should locate a ditch on the side of Mexico. It is prime ground for which to seek cover. The safest place is of the road and instruct riders to take billowing super-cell thunderstorms, in an interior hallway on the lowest cover in it. The bus should be parked which may produce tornadoes. Many possible level, under a staircase, or in a far away from the people to prevent Kansas residents recognize this and designated shelter area. -

3.2 an Evaluation of Tornado Intensity Using Velocity and Strength Attributes from the Wsr-88D Mesocyclone Detection Algorithm

3.2 AN EVALUATION OF TORNADO INTENSITY USING VELOCITY AND STRENGTH ATTRIBUTES FROM THE WSR-88D MESOCYCLONE DETECTION ALGORITHM Darrel M. Kingfield*,1,2, James G. LaDue3, and Kiel L. Ortega1,2 1Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies (CIMMS), Norman, OK 2NOAA/OAR/National Severe Storms Laboratory (NSSL), Norman, OK 3NOAA/NWS/OCWWS/Warning Decision Training Branch (WDTB), Norman, OK 1. INTRODUCTION undergone several improvements since these studies, including the integration of super-resolution data. National Weather Service (NWS) service Super-resolution data (Torres and Curtis, 2007) at the assessments following the 2011 April 27 southeast split-cut elevations reduces the effective beamwidth to US tornado outbreak, and the 2011 May 22 Joplin 1.02 from the legacy 1.38 , allowing for vortex tornado found that the population failed to personalize signatures⁰ to be resolved at longer⁰ ranges from the the potential severity of the tornadoes for which they radar (Brown et al. 2002; Brown et al. 2005). In this were warned. The lack of specific information paper, we investigate how the MDA output correlates contained within the warnings has been cited as a to maximum intensity found in a tornado path. major reason why more action was not taken (NOAA, 2011a, 2011b). As a result, a number of meetings 2. DATA & METHODS amongst government, the private and the academic sectors have begun to formulate a plan to improve 2.1 Acquisition & Playback impact-based warning services. In fact, this is the number one goal of the Weather Ready Nation The initial tornado track dataset was composed initiative within the NWS (NOAA, 2012). -

Observations and Laboratory Simulations of Tornadoes in Complex Topographical Regions Christopher D

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2012 Observations and Laboratory Simulations of Tornadoes in Complex Topographical Regions Christopher D. Karstens Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Atmospheric Sciences Commons, and the Meteorology Commons Recommended Citation Karstens, Christopher D., "Observations and Laboratory Simulations of Tornadoes in Complex Topographical Regions" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12778. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12778 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Observations and laboratory simulations of tornadoes in complex topographical regions by Christopher Daniel Karstens A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Meteorology Program of Study Committee: William A. Gallus, Jr., Major Professor Partha P. Sarkar Bruce D. Lee Catherine A. Finley Raymond W. Arritt Xiaoqing Wu Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2012 Copyright © Christopher Daniel Karstens, 2012. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................. -

Workshop on Weather Ready Nation: Science Imperatives for Severe Thunderstorm Research, Held 24-26 April, 2012 in Birmingham AL

Workshop on Weather Ready Nation: Science Imperatives for Severe Thunderstorm Research, Held 24-26 April, 2012 in Birmingham AL Sponsored by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and National Science Foundation Final Report Edited by Michael K. Lindell, Texas A&M University and Harold Brooks, National Severe Storms Laboratory Hazard Reduction & Recovery Center Texas A&M University College station TX 77843-3137 17 September 2012 Executive Summary The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) workshop sponsored a workshop entitled Weather Ready Nation: Science Imperatives for Severe Thunderstorm Research on 24-26 April, 2012 in Birmingham Alabama. Prior to the workshop, teams of authors completed eight white papers, which were read by workshop participants before arriving at the conference venue. The workshop’s 63 participants—representing the disciplines of civil engineering, communication, economics, emergency management, geography, meteorology, psychology, public health, public policy, sociology, and urban planning—participated in three sets of discussion groups. In the first set of discussion groups, participants were assigned to groups by discipline and asked to identify any research issues related to tornado hazard response that had been overlooked by the 2011 Norman Workshop report (UCAR, 2012) or the white papers (see Appendix A). In the second set of discussion groups, participants were distributed among interdisciplinary groups and asked to revisit the questions addressed in the disciplinary groups, identify any interdependencies across disciplines, and recommend criteria for evaluating prospective projects. In the third set of discussion groups, participants returned to their initial disciplinary groups and were asked to identify and describe at least three specific research projects within the research areas defined by their white paper(s) and to assess these research projects in terms of the evaluation criteria identified in the interdisciplinary groups. -

A Background Investigation of Tornado Activity Across the Southern Cumberland Plateau Terrain System of Northeastern Alabama

DECEMBER 2018 L Y Z A A N D K N U P P 4261 A Background Investigation of Tornado Activity across the Southern Cumberland Plateau Terrain System of Northeastern Alabama ANTHONY W. LYZA AND KEVIN R. KNUPP Department of Atmospheric Science, Severe Weather Institute–Radar and Lightning Laboratories, Downloaded from http://journals.ametsoc.org/mwr/article-pdf/146/12/4261/4367919/mwr-d-18-0300_1.pdf by NOAA Central Library user on 29 July 2020 University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, Alabama (Manuscript received 23 August 2018, in final form 5 October 2018) ABSTRACT The effects of terrain on tornadoes are poorly understood. Efforts to understand terrain effects on tornadoes have been limited in scope, typically examining a small number of cases with limited observa- tions or idealized numerical simulations. This study evaluates an apparent tornado activity maximum across the Sand Mountain and Lookout Mountain plateaus of northeastern Alabama. These plateaus, separated by the narrow Wills Valley, span ;5000 km2 and were impacted by 79 tornadoes from 1992 to 2016. This area represents a relative regional statistical maximum in tornadogenesis, with a particular tendency for tornadogenesis on the northwestern side of Sand Mountain. This exploratory paper investigates storm behavior and possible physical explanations for this density of tornadogenesis events and tornadoes. Long-term surface observation datasets indicate that surface winds tend to be stronger and more backed atop Sand Mountain than over the adjacent Tennessee Valley, potentially indicative of changes in the low-level wind profile supportive to storm rotation. The surface data additionally indicate potentially lower lifting condensation levels over the plateaus versus the adjacent valleys, an attribute previously shown to be favorable for tornadogenesis.