DELIUS and HIS VIOLIN CONCERTO a Performer’S Viewpoint by Tasmin Little

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Makes Me Feel Drawn to KROKE Music Is Spiritual Reality of the Musicians, This Means Honesty and Authenticity of the Music

What makes me feel drawn to KROKE music is spiritual reality of the musicians, this means honesty and authenticity of the music. Nigel Kennedy The music is too dark to really represent traditional klezmer. At times, it is almost as if the Velvet Underground have been reborn as a klezmer band. Ari Davidov KROKE live are a hair-raisingly brilliant, unforgettable experience. John Lusk At times they sound jazzy, at times contemporary, at times classical. Their music is at once passionate and danceable. Dominic Raui KROKE (which means Kraków in Yiddish) was formed in 1992 by three friends and graduates of the Kraków Academy of Music: Jerzy Bawoł (accordion), Tomasz Kukurba (viola) and Tomasz Lato (double bass). The members of the group completed all stages of standard music education, including contemporary music. KROKE began by playing klezmer music, which is deeply set in Jewish tradition, and adding a strong influence of Balkan music. Currently, they draw inspiration from a variety of ethnic music from around the world, combining it with elements of jazz and improvisation, creating their own distinctive style. Initially, KROKE performed only in clubs and galleries situated in Kazimierz, a former Jewish district of Kraków. There, for the first time, one could listen to KROKE's songs. They later recorded their first cassette released at their own expense in 1993. While performing at the Ariel gallery, they came to the attention of Steven Spielberg, who was shooting Schindler's List in Kraków at the time. Spielberg invited them to Jerusalem, where he was shooting the final scenes. The group performed a concert at the Survivors' Reunion for those of Oskar Schindler's list who made it through the war. -

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

Computer Courses for Kids & Teens

Sparkling 22nd season for Proms MICHAEL ELEFTHERIADES Other free lunchtime concerts The Henrietta Barnett School is NIGEL SUTTON were a delight from first to last. much appreciated. Of special note were prize-winning This year’s programme of harpists Klara Woskowiak and walks was well attended, including Elizabeth Bass; young musicians exploration of the Suburb itself Adi Tal on cello and Nadav to hidden architectural treasures Hertzka on piano; and the in the City of London. organ recital by Tom Winpenny GOOD CAUSES in The Free Church. As ever, the many volunteers PRICELESS that make Proms so special did The Literary Festival weekend outstanding work, from providing also offered priceless moments, home-baked cakes for the LitFest including a conversation between Cafe and pouring Pimm’s in the Phyllida Law and Piers Plowright, refreshments marquee to shifting with the author effortlessly furniture, stewarding and Little Wolf Gang’s musical storytelling enthralled its audience charming all present. Itamar general organisation. Tasmin Little and Piers Lane Srulovich and Sarit Packer of Proms at St Jude’s raises The weather turned a kindly face and drama, she returned to the Honey & Co made everyone eager money for two causes that Spring Wordsearch on Proms, with (mostly) sunny stage in a glorious Union Jack to learn Middle Eastern cookery touch many lives, Toynbee days and balmy evenings filled evening gown, bringing the and delighted the audience with Hall’s ASPIRE programme and winner with music, talks, walks and fun audience to its feet as her rich free samples of cake! the North London Hospice. -

2012-0331 Program.Pdf

I\TI\OI)~I ClIO:-;~ Welcorne to Songs ofLight! JUSllikc the anists oftheir day, musicians ofthe Impressionistic CI"'J were intrigued with the cfTt.'C(S ofligtll and 50"0",11 to portray this in their music. With diminished light. the harsh cfTetts ofindustrialization were muted and these llt."\\ landst<q>cs Wert softened and made bc-Jutiful again. l1lis aftcmoon's program is filled wim ethereal depietions of light by Delius. Dehll"S)', and l-Io1st as well a~ with a sparkling new work by Charles Beslor. lei these airy musical work..<; lIallspon you to a time ofday where healilifulligiu softens the lrOublcs ofthe world bringingoullhe best ofany place. Enjo}! ,. As Illusie is lhe poetry OfSOlilld. so is paiming Ihe poclry ofsight. ~ - JUfIlt'JAblJOIf AfcNetillflllfJtler W:.ashillg'lotl Ml'tropolil.U1 rhilhanllonic. UI~"SSCS James. Music Dirt:('lOf & Condm:lor Ulys.<iCS S. James is a fonner lromhonist who studied in BOSlOll aud at Tauglcwood ..•..ith William Gibson. principal trombonist of the Bostoll Symphony On:heslra. He grddlllHcd in 1958 ....ith honurs in llIusi<: from Brown University. Mtcr a 20 yCM ~'aIttr as a surfoc-c ....~Mfare Naval Officer. followed by a second tareer as an organization and management de...e1opmem consultam. he bn-arne the music dire~1or and priocipal condtl~1or of Washington Metropolitan Philharmonic Association in 1985. The Assodation sponsors Washington Metropolitan Philharmonic. Washington ~lctropolitan YOUlh Orchestra. Washington Metropolitan Concen Orchestrd. a weekly summer chamber musie series at The Lyceum ill Old Towll Alexandria. and all anllual cOl1lpo~ition COllllletition for the Mid-Atlantic StUll'S. -

Summer Festival of Chamber Music

Summer Festival of Chamber Music Paxton House, Scottish Borders Friday 19 – Sunday 28 July 2019 Welcome to Music at Paxton Fri 19 July, 7pm · 15 mins Fri 19 July, 7.30pm · 2 hrs /MusicatPaxton Picture Gallery, Paxton House Picture Gallery, Paxton House Festival 2019! #MaP2019 — — Festival Introductory Talk Paul Lewis Piano Angus Smith, — We are delighted that so many outstanding musicians have Music At Paxton Artistic Director Haydn Piano Sonata in E minor, agreed to come to Paxton House this summer, bringing with — Hob. XVI:34 them varied programmes of wonderful music that offer many In this brief festival curtain-raiser, Angus Brahms Three Intermezzi for captivating and entertaining experiences. Smith will shed light on the process of Piano, Op. 117 assembling the 2019 festival, revealing Beethoven Seven Bagatelles, Op. 33 It is a particular pleasure to announce that the prodigiously some of the surprising stories that lie Haydn Piano Sonata in E flat, gifted and engaging Maxwell String Quartet is to be Music behind the choices of composers and Hob. XVI:52 at Paxton’s Associate Ensemble for 2019–21. This young Scottish group is pieces. making great and rapid strides internationally, delighting audiences and critics Paul Lewis is regarded as one of the on their maiden tour of the USA earlier this year. They will present a variety of FREE EVENT to opening concert ticket holders leading pianists of his generation and concerts and community activities for us during their residency, and we also one of the world’s foremost interpreters invite you to meet the players during the Festival – before, during and after Please note that the duration of of central European classical repertoire. -

BRICUP Newsletter 68 September 2013

BRICUP Newsletter 68 September 2013 www.bricup.org.uk [email protected] CONTENTS Kennedy, an enfant terrible of the classical music world , had not played at the Proms for years but P 1. Sound and fury at the Proms over took advantage of a radical mix of programmes this “apartheid” remark time to revisit the Four Seasons with a number of jazz musicians, his own largely Polish Orchestra of P 2. The PACBI Column Life and 17 players from the Palestine Strings wearing trademark keffiyehs. Aged between 12 and On the Academic Boycott Front: A 23, these protégées of the Edward Said National Pioneering Campaign Conservatory of Music demonstrated considerable artistry in one of the world’s greatest performance spaces. No wonder the Zionist reaction to their P 4. The turning of the screw mentor’s solidarity comment was so swift and strong. P 6. Hasbara arrives at the Edinburgh Within days the Jewish Chronicle announced with Fringe satisfaction that the BBC intended deleting Kennedy’s remark from its edited TV broadcast of the concert. Baroness Ruth Deech, a prominent P 7. Notices. Zionist and former BBC governor, had pronounced his words “offensive and untrue” and unfit to be **** heard during a Prom concert. The BBC, saying they Sound and fury at the Proms over did not “fall within the editorial remit of the proms as a classical music festival,” duly obliged. The “apartheid” remark critically-acclaimed concert went out on BBC4 on August 23 without the offending comments. Violinist Nigel Kennedy sent Israel’s apologists into a mighty spin during a Promenade concert in In the interim BRICUP chairman Jonathan London on August 8 when he used the word Rosenhead had joined supporters of Jews for “apartheid” to refer to the life circumstances of the Boycotting Israeli Goods, among them actress young Palestinian musicians with whom he was Miriam Margolyes and writer/comedian Alexei sharing the stage. -

Menuhin Competition Returns to London in 2016 in Celebration of Yehudi Menuhin's Centenary

Menuhin Competition returns to London in 2016 in celebration of Yehudi Menuhin's Centenary 7-17 April 2016 The Menuhin Competition - the world’s leading competition for violinists under the age of 22 – announces its return to London in 2016 in celebration of Yehudi Menuhin’s centenary. Founded by Yehudi Menuhin in 1983 and taking place in a different international city every two years, the Competition returns to London in 2016 after first being held there in 2004. The centenary event will take place in partnership with some of the UK’s leading music organisations: the Royal Academy of Music, the Philharmonia Orchestra, Southbank Centre, the Yehudi Menuhin School and the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain. It will be presented in association with the BBC Concert Orchestra and BBC Radio 3 which will broadcast the major concerts. Yehudi Menuhin lived much of his life in Britain, and his legacy - not just as one of the greatest violinists of the 20th century, but as an ambassador for music education - is the focus of all the Competition’s programming. More festival of music and cultural exchange than mere competition, the Menuhin Competition in 2016 will be a rich ten-day programme of concerts, masterclasses, talks and participatory activities with world-class performances from candidates and jury members alike. Competition rounds take place at the Royal Academy of Music, with concerts held at London’s Southbank Centre. 2016 jury members include previous winners who have gone on to become world class soloists: Tasmin Little OBE, Julia Fischer and Ray Chen. Duncan Greenland, Chairman of the Menuhin Competition comments: “We are delighted to be bringing the Competition to London in Menuhin’s centenary year and working with such prestigious partners. -

557242Bk Delius EC Sono 26/2/04 8:39 PM Page 12

557242bk Delius EC Sono 26/2/04 8:39 PM Page 12 DDD Tintner Memorial Edition Vol.10 8.557242 DELIUS Violin Concerto and other orchestral music Philippe Djokic, Violin Symphony Nova Scotia • Georg Tintner 557242bk Delius EC Sono 26/2/04 8:39 PM Page 2 TINTNER MEMORIAL EDITION • VOLUME 10 TINTNER MEMORIAL EDITION • 12 VOLUMES Frederick Delius (1862-1934) Vol.1 MOZART Symphonies Nos. 31 ‘Paris’, 35 ‘Haffner’ & 40 8.557233 Violin Concerto • Irmelin Prelude • La Calinda • The Walk to the Paradise Garden Vol. 2 SCHUBERT Symphonies Nos. 8 ‘Unfinished’ & 9 ‘The Great’ 8.557234 Intermezzo from ‘Fennimore and Gerda’ • On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring With spoken introduction by Georg Tintner Summer Night on the River • Sleigh Ride Performances recorded 5-6th December 1991 Vol. 3 BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 4 / SCHUMANN Symphony No.2 8.557235 Though Delius was born (as Fritz Theodore Albert, on amanuensis Eric Fenby in 1931. With spoken introductions by Georg Tintner 29th January 1862) in Bradford, England, of German In 1897 Delius completed his third opera, Koanga, Vol. 4 HAYDN Symphonies Nos.103 ‘Drumroll’ & 104 ‘London’ 8.557236 parents, he was the true cosmopolitan. He lived most of about Creole society in Louisiana and thus the first With spoken introduction by Georg Tintner his life in France, Scandinavia and America, and his African-American opera. The dance La Calinda, which music shows traces of them all. After a rather stern appeared in an earlier version in the Florida Suite, is Vol. 5 BRAHMS Symphony No. 3 & Serenade No. 2 8.557237 upbringing Delius was compelled to join the family one of Delius’ best-known and loveliest pieces. -

Jon Lord June 9 1941 – July 16 2012

Jon Lord June 9 1941 – July 16 2012 Founder member of Deep Purple, Jon Lord was born in Leicester. He began playing piano aged 6, studying classical music until leaving school at 17 to become a Solicitor’s clerk. Initially leaning towards the theatre, Jon moved to London in 1960 and trained at the Central School of Speech and Drama, winning a scholarship, and paying for food and lodgings by performing in pubs. In 1963 he broke away from the school with a group of teachers and other students to form the pioneering London Drama Centre. A year later, Jon “found himself“ in an R and B band called The Artwoods (fronted by Ronnie Wood’s brother, Art) where he remained until the summer of 1967. During this period, Jon became a much sought after session musician recording with the likes of Elton John, John Mayall, David Bowie, Jeff Beck and The Kinks (eg 'You Really Got Me'). In December 1967, Jon met guitarist Richie Blackmore and by early 1968 the pair had formed Deep Purple. The band would pioneer hard rock and go on to sell more than 100 million albums, play live to more than 10 million people, and were recognized in 1972 by The Guinness Book of World Records as “the loudest group in the world”. Deep Purple’s debut LP “Shades of Deep Purple” (1968) generated the American Top 5 smash hit “Hush”. In 1969, singer Ian Gillan and bassist Roger Glover joined and the band’s sound became heaver and more aggressive on “Deep Purple in Rock” (1970), where Jon developed a groundbreaking new way of amplifying the sound of the Hammond organ to match the distinctive sound of the electric guitar. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op

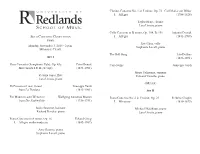

Clarinet Concerto No. 1 in F minor, Op. 73 Carl Maria von Weber I. Allegro (1786-1826) Taylor Heap, clarinet Lara Urrutia, piano Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104, B. 191 Antonin Dvorák SOLO CONCERTO COMPETITION I. Allegro (1841-1904) Finals Xue Chen, cello Monday, November 3, 2014 - 2 p.m. Stephanie Lovell, piano MEMORIAL CHAPEL The Bell Song Léo Delibes SET I (1836-1891) Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op. 43a Peter Benoit Caro Nome Guiseppe Verdi Movements I & II (excerpt) (1834-1901) Mayu Uchiyama, soprano Victoria Jones, flute Edward Yarnelle, piano Lara Urrutia, piano - BREAK - Di Provenza il mar, il suol Giuseppe Verdi from La Traviata (1813-1901) SET II Ein Madehen oder Weibchen Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21 Frédéric Chopin from Die Zauberflöte (1756-1791) I. Maestoso (1810-1849) Justin Brunette, baritone Michael Malakouti, piano Richard Bentley, piano Lara Urrutia, piano Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 Edvard Grieg I. Allegro molto moderato (1843-1907) Amy Rooney, piano Stephanie Lovell, piano Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle Charles Gounod ABOUT THE CONCERTO COMPETITION from Roméo et Juliette (1818-1893) Beginning in 1976, the Concerto Competition has become an annual event Cruda Sorte Gioacchino Rossini for the University of Redlands School of Music and its students. Music from L’Ataliana in Algeri (1792-1868) students compete for the coveted prize of performing as soloist with the Redlands Symphony Orchestra, the University Orchestra or the Wind Jordan Otis, soprano Ensemble. Twyla Meyer, piano This year the Preliminary Rounds of the Competition took place on Friday, October 31st and Saturday, November 1st. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No.