Stringshift Exegesis Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition

Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition by William D. Scott Bachelor of Arts, Central Michigan University, 2011 Master of Music, University of Michigan, 2013 Master of Arts, University of Michigan, 2015 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by William D. Scott It was defended on March 28, 2019 and approved by Mark A. Clague, PhD, Department of Music James P. Cassaro, MA, Department of Music Aaron J. Johnson, PhD, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Michael C. Heller, PhD, Department of Music ii Copyright © by William D. Scott 2019 iii Michael C. Heller, PhD Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition William D. Scott, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2019 The term Latin jazz has often been employed by record labels, critics, and musicians alike to denote idioms ranging from Afro-Cuban music, to Brazilian samba and bossa nova, and more broadly to Latin American fusions with jazz. While many of these genres have coexisted under the Latin jazz heading in one manifestation or another, Panamanian pianist Danilo Pérez uses the expression “Pan-American jazz” to account for both the Afro-Cuban jazz tradition and non-Cuban Latin American fusions with jazz. Throughout this dissertation, I unpack the notion of Pan-American jazz from a variety of theoretical perspectives including Latinx identity discourse, transcription and musical analysis, and hybridity theory. -

Flamenco Jazz: an Analytical Study

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2016 Flamenco Jazz: an Analytical Study Peter L. Manuel CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/306 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Journal of Jazz Studies vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 29-77 (2016) Flamenco Jazz: An Analytical Study Peter Manuel Since the 1990s, the hybrid genre of flamenco jazz has emerged as a dynamic and original entity in the realm of jazz, Spanish music, and the world music scene as a whole. Building on inherent compatibilities between jazz and flamenco, a generation of versatile Spanish musicians has synthesized the two genres in a wide variety of forms, creating in the process a coherent new idiom that can be regarded as a sort of mainstream flamenco jazz style. A few of these performers, such as pianist Chano Domínguez and wind player Jorge Pardo, have achieved international acclaim and become luminaries on the Euro-jazz scene. Indeed, flamenco jazz has become something of a minor bandwagon in some circles, with that label often being adopted, with or without rigor, as a commercial rubric to promote various sorts of productions (while conversely, some of the genre’s top performers are indifferent to the label 1). Meanwhile, however, as increasing numbers of gifted performers enter the field and cultivate genuine and substantial syntheses of flamenco and jazz, the new genre has come to merit scholarly attention for its inherent vitality, richness, and significance in the broader jazz world. -

Towards an Ethnomusicology of Contemporary Flamenco Guitar

Rethinking Tradition: Towards an Ethnomusicology of Contemporary Flamenco Guitar NAME: Francisco Javier Bethencourt Llobet FULL TITLE AND SUBJECT Doctor of Philosophy. Doctorate in Music. OF DEGREE PROGRAMME: School of Arts and Cultures. SCHOOL: Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. Newcastle University. SUPERVISOR: Dr. Nanette De Jong / Dr. Ian Biddle WORD COUNT: 82.794 FIRST SUBMISSION (VIVA): March 2011 FINAL SUBMISSION (TWO HARD COPIES): November 2011 Abstract: This thesis consists of four chapters, an introduction and a conclusion. It asks the question as to how contemporary guitarists have negotiated the relationship between tradition and modernity. In particular, the thesis uses primary fieldwork materials to question some of the assumptions made in more ‘literary’ approaches to flamenco of so-called flamencología . In particular, the thesis critiques attitudes to so-called flamenco authenticity in that tradition by bringing the voices of contemporary guitarists to bear on questions of belonging, home, and displacement. The conclusion, drawing on the author’s own experiences of playing and teaching flamenco in the North East of England, examines some of the ways in which flamenco can generate new and lasting communities of affiliation to the flamenco tradition and aesthetic. Declaration: I hereby certify that the attached research paper is wholly my own work, and that all quotations from primary and secondary sources have been acknowledged. Signed: Francisco Javier Bethencourt LLobet Date: 23 th November 2011 i Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to thank all of my supervisors, even those who advised me when my second supervisor became head of the ICMuS: thank you Nanette de Jong, Ian Biddle, and Vic Gammon. -

Jorge Pardo: Huellas Featuring the Juanito Pascual Trio

MUSIC Jorge Pardo: Huellas featuring WASHINGTON, D.C. the Juanito Pascual Trio Thu, November 17, 2016 7:30 pm Venue Former Residence of the Ambassadors of Spain, 2801 16th Street NW, Washington, DC 20009 View map Credits Presented by SPAIN arts & culture with the support of the Permanent Observer Mission of Spain to the OAS. Image by Angel Vicente Legendary saxophonist Jorge Pardo comes to D.C. this November as part of his U.S. tour for a unique evening of jazz and flamenco featuring the Juanito Pascual Trio. Whoever loves Jazz, loves Jorge Pardo. Whoever loves Flamenco, loves Jorge Pardo. Those who have a passion for music must love Jorge Pardo because he chants through his flute, is able to let his saxophone complain, enjoys the rhythm and passes his magic on to his instruments. Jorge Pardo, saxophone and flute player, is one of the most outstanding and consistent revelations of the flamenco jazz fusion. He, together with Paco de Lucía and Camarón de la Isla, helped forging a new musical language melding jazz and flamenco. His playing style has become a referential point. He shared ideas, music and experiences during 20 years, with the master of flamenco guitar, Paco de Lucia. During these years of tours, records and coexistence, they created a new musical language known as Flamenco Jazz or Flamenco Fusion. This music had a strong flamenco nature and was composed also off classic works and world rhythms. His discography extends beyond 20 recordings as leader. He also collaborated and exchanged experiences with other artists all over the world, such as Chick Corea, Paco de Lucía, Tete Montoliu, Marcus Miller, Pat Metheny, etc. -

Read Liner Notes

Cover Photo: Paul Winter Consort, 1975 Somewhere in America (Clockwise from left: Ben Carriel, Tigger Benford, David Darling, Paul Winter, Robert Chappell) CONSORTING WITH DAVID A Tribute to David Darling Notes on the Music A Message from Paul: You might consider first listening to this musical journey before you even read the titles of the pieces, or any of these notes. I think it could be interesting to experience how the music alone might con- vey the essence of David’s artistry. It would be ideal if you could find a quiet hour, and avail yourself of your fa- vorite deep-listening mode. For me, it’s flat on the floor, in total darkness. In any case, your listening itself will be a tribute to David. For living music, With gratitude, Paul 2 1. Icarus Ralph Towner (Distant Hills Music, ASCAP) Paul Winter / alto sax Paul McCandless / oboe David Darling / cello Ralph Towner / 12-string guitar Glen Moore / bass Collin Walcott / percussion From the album Road Produced by Phil Ramone Recorded live on summer tour, 1970 This was our first recording of “Icarus” 2. Ode to a Fillmore Dressing Room David Darling (Tasker Music, ASCAP) Paul Winter / soprano sax Paul McCandless / English horn, contrabass sarrusophone David Darling / cello Herb Bushler / Fender bass Collin Walcott / sitar From the album Icarus Produced by George Martin Recorded at Seaweed Studio, Marblehead, Massachusetts, August, 1971 3 In the spring of 1971, the Consort was booked to play at the Fillmore East in New York, opening for Procol Harum. (50 years ago this April.) The dressing rooms in this old theatre were upstairs, and we were warming up our instruments there before the afternoon sound check. -

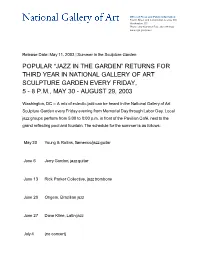

Popular “Jazz in the Garden” Returns for Third Year in National Gallery of Art Sculpture Garden Every Friday, 5 - 8 P.M., May 30 - August 29, 2003

Office of Press and Public Information Fourth Street and Constitution Av enue NW Washington, DC Phone: 202-842-6353 Fax: 202-789-3044 www.nga.gov/press Release Date: May 11, 2003 | Summer in the Sculpture Garden POPULAR “JAZZ IN THE GARDEN” RETURNS FOR THIRD YEAR IN NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART SCULPTURE GARDEN EVERY FRIDAY, 5 - 8 P.M., MAY 30 - AUGUST 29, 2003 Washington, DC -- A mix of eclectic jazz can be heard in the National Gallery of Art Sculpture Garden every Friday evening from Memorial Day through Labor Day. Local jazz groups perform from 5:00 to 8:00 p.m. in front of the Pavilion Café, next to the grand reflecting pool and fountain. The schedule for the summer is as follows: May 30 Young & Rollins, flamenco/jazz guitar June 6 Jerry Gordon, jazz guitar June 13 Rick Parker Collective, jazz trombone June 20 Origem, Brazilian jazz June 27 Dave Kline, Latin jazz July 4 (no concert) July 11 Young & Rollins, flamenco/jazz guitar July 18 Thad Wilson Jazz Orchestra July 25 Joshua Bayer Quartet, jazz guitar Aug 1 Dave Mosick Trio, jazz guitar Aug 8 Young & Rollins, flamenco/jazz guitar Aug 15 Thad Wilson Quintet, jazz trumpet Aug 22 Jerry Gordon, jazz guitar Aug 29 Origem, Brazilian jazz Sept 5 Bossalingo Latin jazz Sept 12 Dave Kline Latin jazz Sept 19 Joshua Bayer Quartet jazz bass Sept 26 Young & Rollins flamenco/jazz guitar During the jazz concerts, the Pavilion Café in the Sculpture Garden offers a special menu of tapas and refreshments served either inside the café or from carts located on the two patios. -

Nuevo Flamenco: Re-Imagining Flamenco in Post-Dictatorship Spain

Nuevo Flamenco: Re-imagining Flamenco in Post-dictatorship Spain Xavier Moreno Peracaula Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD Newcastle University March 2016 ii Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements v Introduction 1 Chapter One The Gitano Atlantic: the Impact of Flamenco in Modal Jazz and its Reciprocal Influence in the Origins of Nuevo Flamenco 21 Introduction 22 Making Sketches: Flamenco and Modal Jazz 29 Atlantic Crossings: A Signifyin(g) Echo 57 Conclusions 77 Notes 81 Chapter Two ‘Gitano Americano’: Nuevo Flamenco and the Re-imagining of Gitano Identity 89 Introduction 90 Flamenco’s Racial Imagination 94 The Gitano Stereotype and its Ambivalence 114 Hyphenated Identity: the Logic of Splitting and Doubling 123 Conclusions 144 Notes 151 Chapter Three Flamenco Universal: Circulating the Authentic 158 Introduction 159 Authentic Flamenco, that Old Commodity 162 The Advent of Nuevo Flamenco: Within and Without Tradition 184 Mimetic Sounds 205 Conclusions 220 Notes 224 Conclusions 232 List of Tracks on Accompanying CD 254 Bibliography 255 Discography 270 iii Abstract This thesis is concerned with the study of nuevo flamenco (new flamenco) as a genre characterised by the incorporation within flamenco of elements from music genres of the African-American musical traditions. A great deal of emphasis is placed on purity and its loss, relating nuevo flamenco with the whole history of flamenco and its discourses, as well as tracing its relationship to other musical genres, mainly jazz. While centred on the process of fusion and crossover it also explores through music the characteristics and implications that nuevo flamenco and its discourses have impinged on related issues as Gypsy identity and cultural authenticity. -

One Page Oregon Biography

O R E G O N B I O G R A P H Y Without a doubt O R E G O N is one of the finest groups l a t e r, O R E G O N moved to Elektra/Asylum Records. Its ever to paint a musical landscape of such global first release on that label, Out of the Woods, r e a c h e d proportions. For three decades O R E G O N has inspired a decidedly wider audience and was included in the 101 audiences in renowned concert halls including Best Jazz Albums list. They were enjoying imm e n s e Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Berlin Philharmonic popularity when in November 1984, Walcott died in an H a l l, and Vienna’s Mozartsaal; in international jazz auto accident in the former East Germany, leaving the clubs and at major festivals on tour throughout ECM album C r o s s i n g as his final document. Over the every continent. next five years, percussionist Trilok Gurtu played on three albums with the band. Upon his departure the three original members continued their creative development as a trio. For the 1996 Intuition recording Northwest Passage, the group incorporated drummer MARK WALKER on the Indie Award winning record. He soon after became their newest member. In June 1999 the band traveled to Moscow to record the double CD O R E G O N I N M O S C O W for I n t u i t i o n. -

Ralph Towner Works Mp3, Flac, Wma

Ralph Towner Works mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Works Country: US Style: Contemporary Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1800 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1532 mb WMA version RAR size: 1386 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 176 Other Formats: DMF WMA MP1 DXD AIFF DMF MIDI Tracklist Hide Credits Oceanus A1 10:59 Bass – Eberhard WeberDrums, Percussion – Jon ChristensenSaxophone – Jan Garbarek Blue Sun A2 7:15 Piano, Synthesizer, Percussion – Ralph Towner New Moon A3 Bass – Eddie GomezCello – David DarlingDrums, Percussion – Michael DiPasquaTrumpet, 7:21 Flugelhorn – Kenny Wheeler Beneath The Evening Sky B1 7:00 Cello – David DarlingPiano – Ralph Towner The Prince And The Sage B2 6:18 Synthesizer – Ralph Towner Nimbus B3 Bass – Eberhard WeberDrums, Percussion – Jon ChristensenPiano – Ralph 6:26 TownerSaxophone, Flute – Jan Garbarek Credits Design – Dieter Rehm Engineer – Jan Erik Kongshaug Guitar – Ralph Towner Producer – Manfred Eicher Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 781182026841 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year 823 268-2 Ralph Towner Works (CD, Comp) ECM Records 823 268-2 Germany Unknown 823 268-4 Ralph Towner Works (Cass, Comp) ECM Records 823 268-4 Canada 1984 823 268-4 Ralph Towner Works (Cass, Comp, RE) ECM Records 823 268-4 US Unknown 823 268-1 Ralph Towner Works (LP, Comp) ECM Records 823 268-1 Germany 1984 823 268-4 Ralph Towner Works (Cass, Comp) ECM Records 823 268-4 Germany 1984 Related Music albums to Works by Ralph Towner Ralph Towner - Old Friends, New Friends Ralph Towner - Anthem Oregon - Ecotopia Ralph Towner - Solstice Ralph Towner / Gary Burton - Slide Show Ralph Towner, D. -

JAZZMADRID 2016 Festival Internacional De Jazz De Madrid Del 25 De Octubre Al 30 De Noviembre Del 25 De Octubre Al 30 De Noviembre

JAZZMADRID 2016 Festival Internacional de Jazz de Madrid Del 25 de octubre al 30 de noviembre Del 25 de octubre al 30 de noviembre Dossier de prensa Índice Presentación Programa de conciertos Conde Duque y Fernán Gómez CC de la Villa Otros espacios: Instituto Francés La Noche en Vivo – Jazz con Sabor a Club Debates El jazz en el cine Exposición Información práctica 2 PRESENTACIÓN El jazz en Madrid sigue su camino con paso firme. Y lo hace a través de la cita que en el otoño propone, por tercer año consecutivo, JAZZMADRID. Entre el 25 de octubre y el 30 de noviembre, la afición podrá disfrutar de un apretado calendario musical que, en contraste con el de años anteriores, revela además un aumento notorio en su oferta artística. Serán, aproximadamente, un centenar de conciertos, así como diferentes actividades paralelas relacionadas con el jazz. El festival tendrá desarrollo en diferentes espacios escénicos de la ciudad, pero su centro neurálgico volverá a ser Conde Duque, con la novedad de que, este año, ampliando geografías, también se suma como sede principal el teatro Fernán Gómez. Ambos auditorios darán cabida a los más diversos y destacados nombres de la escena jazzística actual y de siempre. Dave Holland, Madeleine Peyroux, Gregory Porter, Hiromi Uehara o el nuevo grupo de Stanley Clarke, son solo algunos de ellos. Y, en el ámbito local, Pablo Martín Caminero, Kontxi Lorente, Marta Sánchez, Ximo Tébar, O Sister!, Luis Verde y Giulia Valle defienden también sus posiciones. A modo de declaración de principios, el festival cerrará sus actividades con un gran concierto protagonizado por el contrabajista Javier Colina al que se le ha ofrecido "carta blanca" para que sea él mismo el que conforme la banda que considere más oportuna para desarrollar esta actuación. -

ERIC HOFBAUER American Grace MOSTTY

RECORDREVIEWS ERICHOFBAUER MOSTTYOTHER PEOPLE DO THE OREGON AmericanGrace KIttING FamilyTree SlipperyRock! EricHofbauet guitar PaulMc€andless, soprano saxophone, oboe, bass CreativeNation CNM 022 (CD).2012.Creative PeterEvans, piccolo trumpet, trumpet, slide trumpet; clarinet,flutes; Ralph Towner, classical guitar, Nation,prod.; Daniel Cantor, mix, mastering. Jonlrabagon, sopranino, soprano, alto, piano,synthesizer; Glen Moore, bass; Mark DDD?TT:58:27 tenor saxophones,flute; Moppa Elliott,bass; Walker,drums, hand percussion, drum synthesizer CAM JazzCAM 5046 (CD).2012. PERFORMANCE**'***{ KevinShea, drums, percussron ErmannoBasso, (CD). prod.; Oregon,prods.; Johannes Wohlleben, eng. DDD. soNtcs ***** Hot Cup123 2012.Moppa Elliott, RyanStrebet eng. DDD? TT:52:38 TT:60:58 PERFoRMANcE**'**-€ Guitarist Eric Hofbauer, cofounder of PERFoRMANcE***'* +.: sonrcs* *** + soNlcs*r*(*** the Creative Nation label, has become a significant force in Boston's improvised- Oregon still plays with fire and still music scene.Withjust a Guild arch- I saw this bizarre band, known to rts sounds like only one band in the top and an earthy, unadorned sound, fans asMOPDTI! at the BelgradeJazz worid. That sisnature blend of sonori- Hofbauer has blasted away at everything Festival last year. Their midnight concert ties comes from Raloh Towner's lush - &om Charlie Parker,Xric Dolphy, and was an outrageous Dadaist happening, a nylon-string guitar, Paul McCandless's Andrew Hill to Tears for Feari. a-ha- musical debauch of manic virtuosity and keening reeds,and Glen Moore's fluid and Van Halen. His aestheticevokes old deadoan merriment. bass.The runes,mostly wrimen by blues, Americana Tin Pan Alley, bebop, SEppery Ro ck I works because Towner, are bracing little hooks traced and funher fronciers.There's a rule- MOPDIKs more orsanized studio in tight unisons.lmprovisations are breaking spirit but also an impeccable versionof mayhem ii srill mayhem. -

Unbound Jazz: Composing and Performing in a Multi- Cultural Tonality

Unbound Jazz: Composing and Performing in a Multi- Cultural Tonality By Carlo Estolano Commentaries for the PhD folio of compositions University of York Music December 2017 2 3 Unbound Jazz: Composing and Performing in a Multi-Cultural Tonality Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of a PhD degree in Music at The University of York, December 2018 by Carlo Estolano. Abstract This folio is conceived to propose and demonstrate music realisation of original compositions throughout the employment of elements of mainly two distinct sources: a selection from the wide palette of Brazilian folk styles that have improvisation as a strong element, which is internationally acknowledged as Brazilian Jazz; and its intersections with a certain style of European Jazz represented by artists notable by their keenness to combine elements from distinct musical genres with their Classical background, such as Ralph Towner, Jan Garbarek, John Abercrombie, Eberhard Weber, Kenny Wheeler, Terje Rypdal, Keith Jarrett to name a few. Both Brazilian and European approaches to Jazz seem to share processes of appropriation of foreign musical languages, as well as utilising characteristic features of their own traditions. Another common ground is their relation with some elements and procedures of classical music. The methodology to accomplish an organized collection of musical material was to divide them in five major influences, part of them by composers and part by genres notable by having evolved through absorbing elements from distinct cultural sources. In five projects, fifteen original compositions are provided along with their recorded and/or filmed performances and commentaries about the compositional aspects, concerningthe style or composer focused on.