ETHJ Vol-26 No-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The First Defenders Civil War Round Table Newsletter

4 The First Defenders Civil War Round Table Newsletter September 2009 A New Campaign Begins Welcome back to a new season! The programs have been set and promise to impress Round Table members. Mark your calendars now for the 2nd Tuesday of the next 9 months and read on for details... Round Table Business Old Business: On May 12, 2009, President Mike Gabriel called to order the May meeting of the First Defenders Round Table. Dave Fox reported that there were 36 people signed up for the field trip to Frederick with space for 10 more. A report from Roger Cotterill and Dave follows in this newsletter. During the book raffle, it was decided to donate $400 to Richmond, $500 to Monocacy, and $400 to Cedar Creek. The monies were disbursed from the book raffle fund ($700), from the treasury ($500), and from the trip fund ($100). The Election of Officers resulted in the following: President—Joe Schaeffer Vice President—Robert Marks Treasurer—Arlan Christ Membership—Pat Christ Book Raffle/Preservation—Tom Tate Recording Secretary—Richard Kennedy Solicitor—Robert Grim Newsletter—Linda Zeiber Board - at - Large — Dave Fox & Roger Cotterill Program Coordinators—Errol Steffy & Barbara Shafer (Don Stripling will be added if approved by the membership.) New Business: There was a discussion about ordering shirts and hats. The program coordinators would like to give them to speakers who do not receive an honorarium. Further discussion was held during the Board of Directors meeting in June. Richard Kennedy will give more information in his minutes of that meeting. Several trip ideas were talked about for spring of 2010, and it was suggested that we have our own flag for meetings. -

Economics Prof Is Labor Mediator

North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship NCAT Student Newspapers Digital Collections 11-1949 The Register, 1949-11-00 North Carolina Agricutural and Technical State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.library.ncat.edu/atregister Recommended Citation North Carolina Agricutural and Technical State University, "The Register, 1949-11-00" (1949). NCAT Student Newspapers. 104. https://digital.library.ncat.edu/atregister/104 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collections at Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in NCAT Student Newspapers by an authorized administrator of Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THANKSGIVING LITTLE FOXES' November 24 JH\\t mktt\\%t$x December 1-2 "The Cream of College New$" VOL. XLV—No. 2 A. and T. College, Greensboro, N. C, November, 1949 5 CENTS PER COPY Economics Prof Is Labor Mediator Dr. W.E. Williams Strike Arbitrator in N. C. Homecoming—Founders' Day Exercise Strike Arbitrator Most Elaboration in School's History Nearly 15,000 alumni, former stu Founder's Day, or Dudley Day, is In North Carolina dents, and visitors invaded the A. the annual observance of the college and ZT- 'College campus to take part in honor of the late James B. Dudley, Dr. W. E. Williams, professor of in one of the most colorful and elabo one of the founders of the school. AU Economics at A. and T. College, has rate programs in the history o£ the classes were suspended after 9:50 a. -

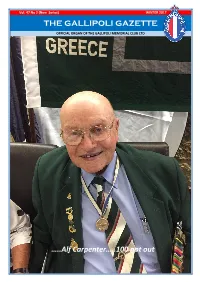

Alf Carpenter…..100 Not Out

Vol. 47 No 2 (New Series) WINTER 2017 THE GALLIPOLI GAZETTE OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE GALLIPOLI MEMORIAL CLUB LTD …..Alf Carpenter…..100 not out 1 EDITORIAL…….. This edition carries a full report on the Gallipoli Art celebration and presented Alf Carpenter with a Prize which again attracted a broad range of entries. certificate of Club Life Membership. We also look at the commemoration of Anzac Day The elevation of John Robertson to Club President at the Club which included the HMAS Hobart at the April Annual Meeting sees the continuity of Association and was highlighted by the 2/4th the strong leadership the Club has benefitted from Australian Infantry Battalion Reunion which over past decades since the Club was lifted out of doubled as celebration of the 100th birthday three financial uncertainty in the early 1990s. "Robbo" days earlier of its Battalion Association President for joined the Committee in 1991 along with outgoing the past 33 years, Alf Carpenter. President Stephen Ware and myself. So, I know first- The numbers at the reunion lunch were bolstered hand of John's strong commitment over many years by the many friends Alf has made among the to the Club and its ideals. The Club also owes a families of his World War Two mates and the massive debt to retiring President Stephen Ware, support he has given to those families as the ranks who has stepped down to be a Committee member of the 2/4th diminished over the years. The new for continuity. Thank you Stephen for your visionary Gallipoli Club President, John Robertson, joined the leadership and prudent financial management over three decades. -

2021 Part 4 Northern Victorian Arms Collectors

NORTHERN VICTORIAN ARMS COLLECTORS GUILD INC. More Majorum 2021 PART 4 Bob Semple tank Footnote in History 7th AIF Battalion Lee–Speed Above Tiger 2 Tank Left Bob Sample Tank 380 Long [9.8 x 24mmR] Below is the Gemencheh Bridge in 1945 Something from your Collection William John Symons Modellers Corner by '' Old Nick '' Repeating Carbine Model 1890 Type 60 Light Anti-tank Vehicle Clabrough & Johnstone .22 rimfire conversion of a Lee-Speed carbine On the Heritage Trail by Peter Ford To the left some water carers at Gallipoli Taking Minié rifle rest before their next trip up. Below painting of the light horse charge at the Nek Guild Business N.V.A.C.G. Committee 2020/21 EXECUTIVE GENERAL COMMITTEE MEMBERS President/Treasurer: John McLean John Harrington Vice Pres/M/ship Sec: John Miller Scott Jackson Secretary: Graham Rogers Carl Webster Newsletter: Brett Maag Peter Roberts Safety Officer: Alan Nichols Rob Keen Sgt. at Arms: Simon Baxter Sol Sutherland Attention !! From the Secretary’S deSk Wanted - The name of the member who in mid-June, made a direct deposit of $125.00 cash into our bank account. I assume that person would like a current membership card, but as you have provided no clues as to who you are, all I can do is include you in the group that received their Annual Subscription Final Notice. Annual Subscriptions - At the time of writing we have 137 fully paid-up members, though one of them is ID unknown. For those that have yet to respond to the final notice, I am still happy to take your money at any time, but I won’t be posting any more reminders, you won’t have a membership card to cover you for Governor in Council Exemptions for Swords Daggers and Replica Firearms and we can’t endorse your firearms license applications or renewals. -

58/32 Infantry Battalion Association Inc. A0059554F

58/32 Infantry Battalion Association Inc. A0059554F February 2016 ( Edition 8 ) 100 Years to the hour A proud Daughter Judith Storey (left) looks on as her fathers plaque is unveiled at his graveside, along with Grandson Danny Keane (centre) and two great-grandsons (left) Andy Keane (right) Brendan Keane The Hon. Tony Smith Speaker of the House of Representatives addresses the gathering. The 58th Battalion is honoured to have had Major William Charles Scurry as one of its finest members, enabling over 10,000 lives to be saved in the Gallipoli evacuation, due to his slow water–drip/delayed rifle fire invention. (pictured below) Bill Higgins who was responsible for the idea and making of our banner. Bill, the 58/32 thanks you so much for your efforts. How proud our Association was, to have its own banner displayed for the first time at MVCC Remembrance Day 2015 The windy day saw MVCC speaker Susan De Prost pictured above with Lt. Col. Don Blanksby, address the gathering by speaking about her Our Vice President and grandfather who enlisted in the 58th Bn. Historian Maj. Bob Prewett also involved with the precision of Andrew Guest above layed a wreath on the banners colour work was behalf of his grand uncle also present and the smile Lt. Eric Chinner who fought with the shows that he was very pleased nd 32 Battalion WW1. with the result. Annual Pompey Elliott Memorial Luncheon th March 11 2016 Invitation Page 5. Remembrance Day continued: Our thanks go to Michael & Susan Phillips for laying the 58th/32nd wreath at the Keilor East RSL. -

THE NEGLECTED REGIMENT: EAST TEXAS HORSEMEN with ZACHARY TAYLOR by Thomas H

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 12 | Issue 2 Article 6 10-1974 The eglecN ted Regiment: East Texas Horsemen with Zachary Taylor Thomas H. Kreneck Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Kreneck, Thomas H. (1974) "The eN glected Regiment: East Texas Horsemen with Zachary Taylor," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 12: Iss. 2, Article 6. Available at: http://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol12/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized administrator of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 22 EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE NEGLECTED REGIMENT: EAST TEXAS HORSEMEN WITH ZACHARY TAYLOR by Thomas H. Kreneck During the Mexican War Texas volunteers served in the ranks of the American army, and earned an enviable martial reputation. When General Zachary Taylor launched his initial invasion of the enemy's country from Matamoros to Monterrey in the summer and early fall of 1846, his force included two regiments of mounted Texans. The more famous ofthese Lone Star partisans was a regiment whose members came from the area that was then considered West Texas, and was commanded by the intrepid Colonel John Coffee Hays. The preoccupation of writers and historians with the activities of the westerners has clearly overshadowed the imporlant services rendered by the East Texas regiment commanded by George Thomas Wood. The purpose of this paper is not only to redress that imbalance by revealing the East Texans in truer focus, but also to explain why they have received less attention than Hays and his men. -

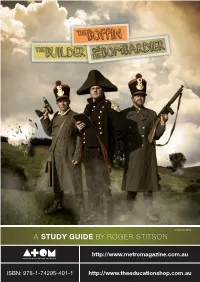

A Study Guide by Roger Stitson

© ATOM 2014 A STUDY GUIDE BY ROGER STITSON http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-401-1 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au General introductory note This study guide contains a range of class (L-R) WILLIAM UPJOHN ‘THE BUILDER’, JOHN CONCANNON ‘THE BOFFIN’, activities relevant to each specific episode. ANTHONY MILLER ‘THE BOMBARDIER’ - PHOTO BY GEOFFREY ELLIS. The activities on each episode are in self- contained sections throughout the study Pty Ltd Valour Images © For unless otherwise stated. Photographs by Stefan Postles guide. As some topics are relevant to all the episodes, there is an introductory section on primary and secondary source material and, later in the study guide, a Series Synopsis section devoted to a general overview of the entire series. There is also a dedicated he Boffin, the Builder and the Bombardier is Media Studies section of activities a fun and fast-paced series of eight ten-min- relevant to the construction, purposes and Tute episodes, in which three mates decon- outcomes of the series. struct history by reconstructing the devices that Episode synopses at the beginning of each made it. Each episode sees our characters uncover section are taken from the series press kit. the secrets of the past by immersing themselves in it – dressing up, with often comedic results – and blowing up ... sometimes just for the fun of it. But beneath the good humour is a well-researched documentary with experimental archaeology – the replication of objects and methods of the past, to Curriculum links • Draw up a list of examples of primary and sec- better interpret and understand them – at its core. -

Hispanic Soldiers of New Mexico in the Service of the Union Army

Fort Union National Monument Hispanic Soldiers of New Mexico in the Service of the Union Army Theme Study prepared by: Dr. Joseph P. Sanchez · Dr. Jerry Gurule Larry D. Miller March 2005 Fort Union National Monument Hispanic Soldiers of New Mexico in the Service of the Union Army Theme Study prepared by: Dr. Joseph P. Sanchez Dr. Jerry Gurule Larry D. Miller March 2005 New Mexico Hispanic Soldiers' Service in the Union Army Hispanic New Mexicans have a long history of military service. As early as 1598, Governor Juan de Onate kept an organized militia drawn from colonists~ Throughout the seventeenth century, encomenderos (tribute collectors) recruited militia units to protect Hispanic settlements and Indian pueblos from Plains warriors. Cater, presidios (garrisoned forts) at Santa Fe and El Paso del Norte housed presidia} soldiers who, accompanied by Indian auxiliaries, served to defend New Mexico. Spanish officials recruited Indian auxiliaries from the various Pueblo tribes as well as Ute warriors among others. In the late eighteenth century, Spain reorganized its military units throughout the Americas to include a regular standing army. Finally, after Mexican independence from Spain, Mexican officials maintained regular army units to defend the newly created nation. Militias assisted regular troops and took their place in their absence when needed. Overall, soldiers under Spain and Mexico protected against Indian raids, made retaliatory expeditions, and escorted mission supply trains, merchants, herders, and the mail. Under Mexico, soldiers protected the borders and arrested foreigners without passports. With the advent ofthe Santa Fe trade in 1821, Mexican soldiers were assigned to customs houses and, to some extent, offered protection to incoming merchants. -

Remembering the Battle of Milliken's Bend

REMEMBERING THE BATTLE OF MILLIKEN’S BEND ___________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History Sam Houston State University ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts ____________ by Isaiah J. Tadlock December, 2018 REMEMBERING THE BATTLE OF MILLIKEN’S BEND by Isaiah J. Tadlock _____________ APPROVED: Brian Matthew Jordan, Ph.D Thesis Director Jadwiga Biskupska, Ph.D Committee Member J. Ross Dancy, D. Phil Committee Member Dr. Abbey Zink, Ph.D Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences ABSTRACT Tadlock, Isaiah J. Remembering the Battle of Milliken’s Bend. Master of Arts (History), December, 2018, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, Texas. On June 7, 1863 Union and Confederate forces clashed at a Federal encampment on the Mississippi River near the town of Milliken’s Bend. While this engagement was influential for the future of the United States Colored Troops, and thus the outcome of the Civil War, it has been largely overlooked by historians and the public at large. The accounts that do exist tend to be more of an overview of the battle rather than an in-depth look at its events and influence. This thesis will closely examine two regiments which faced each other that day in an attempt to provide a better look at the battle, and explain its loss of place in history. The subjects of these analyses will be the 16th Texas Cavalry, Dismounted, and the 11th Louisiana Infantry, African Descent. The events of the battle itself will be covered, in addition to the lives of the men of each regiment before and after the battle. -

A Camera on Gallipoli Has Been Developed by the Australian War Memorial with the Support of the Australian Government’S Commemorations Program

ONLINE LEARNING RESOURCE A camera on Gallipoli has been developed by the Australian War Memorial with the support of the Australian Government’s Commemorations Program. ONLINE LEARNING RESOURCE A camera on Gallipoli This resource has been designed for upper primary and lower secondary students and is intended to be used in conjunction with the travelling exhibition, A camera on Gallipoli. The background information cited in this resource has been taken from the exhibition text, written by Peter Burness. The activities in this resource support the historical skills and content areas within the primary and secondary Australian Curriculum: History. CONTENTS Introduction Who was Charles Ryan? Section 1 Bound for war Case study: Major General Sir William Bridges Questions and activities Section 2 Life for the Anzacs on Gallipoli Case study: General Sir William Birdwood Questions and activities Section 3 No more battles Case study: General Sir Harry Chauvel Questions and activities Introduction Who was Charles Ryan? Charles Ryan’s photographs form an historic record of a campaign that over the past 100 years has entered Australian legend. These images capture the mateship, the stoicism, and the dogged endurance that became the spirit of Anzac. Charles Snodgrass Ryan, born in 1853, was the son of a Victorian pioneer. After completing medical studies in Europe, he set off in search of adventure. Before long he accepted work as a surgeon with the Turkish army in the Turko-Serbian war of 1876, and then in the Russo-Turkish campaign of 1877–78, where his experience of the siege of Plevna led to his receiving the nickname “Plevna”. -

PRESIDENT's MUSINGS DECEMBER 2015 Naval Pride Was Well To

PRESIDENT'S MUSINGS DECEMBER 2015 Naval pride was well to the fore in Port Melbourne on Friday November 27th and in Hastings on Saturday November 28th. We were absolutely delighted with the overall quality and authenticity of the 'Answering the Call' statue our Chief of Navy, Vice Admiral Tim Barrett AO CSC RAN, unveiled In Port Melbourne on the 27th. Admiral Barrett has been very supportive of this project since becoming our leader and his speech prior to the actual unveiling, revealed a depth of knowledge in the project, its conception and objectives. We have obtained a copy of our Chief's speech and I am delighted to share it with you by quoting excerpts from it. I feel it certainly ticks all the boxes. "ANSWERING THE CALL" Port of Melbourne Statue Unveiling. CN Address: QUOTED EXERPTS: I commence my address by remembering and saluting the naval service and the life's work of the late LCDR Mackenzie J Gregory, the former head of the Naval Heritage Foundation. It is very good to have Mac's family with us for this unveiling of his legacy. "Mac" started at the RAN College as a Cadet Midshipman in 1936.He survived the sinking of HMAS CANBERRA and was aboard HMAS SHROPSHIRE in Tokyo Bay when the surrender was signed in 1945. He devoted many years to keeping naval history and heritage alive. The first Council meeting at which Mac proposed the memorial was in October 2008.It was Mac's sustained perseverance, and that of his team, and all those who shared his vision ,which has given us this memorial. -

Colonialism, Native Peoples, and National Identity in Australia and New Zealand ______

THE GREAT WAR: COLONIALISM, NATIVE PEOPLES, AND NATIONAL IDENTITY IN AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History ____________________________________ By Joey Hwang Thesis Committee Approval: Nancy Fitch, Department of History, Chair Jasamin Rostam-Kolayi, Department of History Kristine Dennehy, Department of History Fall, 2017 ABSTRACT The popular perception of the Gallipoli campaign, and the Great War as a whole, as the birthplace of Australia and New Zealand as distinct nations from Britain is not inaccurate. The stories of the ANZACs bravely storming the beaches in Turkey remain a sacred part of their national histories. While most historians recognize that the First World War shaped the two nations, the popular narratives of the war tend to come from a distinctly European perspective. The native peoples of both nations also had a major impact on the development of their national identities, as well as their views of each other. The exploits of the Maori at Gallipoli and the Western Front, as well as continued discrimination against Aboriginal Australians on the home front, had a much stronger influence on the national mythos of both nations than is commonly portrayed. Furthermore, the war’s impact eroded the “colonials’” opinion of Britain, the mother country, and served to only further exacerbate the growing divisions