Remembering the Battle of Milliken's Bend

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political History of Chicago." Nobody Should Suppose That Because the Fire and Police Depart Ments Are Spoken of in This Book That They Are Politi Cal Institutions

THE POLITICAL HISTORY OF CHICAGO. BY M. L. AHERN. First Edition. (COVERING THE PERIOD FROM 1837 TO 1887.) LOCAL POLITICS, FROM THE CITY'S BIRTH; CHICAGO'S MAYORS, .ALDER MEN AND OTHER OFFICIALS; COUNTY AND FE.DERAL OFFICERS; THE FIRE AND POLICE DEPARTMENTS; THE HAY- MARKET HORROR; MISCELLANEOUS. CHIC.AGO: DONOHUE & HENNEBEaRY~ PRINTERS. AND BINDERS. COPYRIGHT. 1886. BY MICHAEL LOFTUS AHERN. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. CONTENTS. PAGE. The Peoples' Party. ........•••.•. ............. 33 A Memorable Event ...... ••••••••••• f •••••••••••••••••• 38 The New Election Law. .................... 41 The Roll of Honor ..... ............ 47 A Lively Fall Campaign ......... ..... 69 The Socialistic Party ...... ..... ......... 82 CIDCAGO'S MAYORS. William B. Ogden .. ■ ■ C ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ e ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ti ■ 87 Buckner S. Morris. .. .. .. .... ... .... 88 Benjamin W. Raymond ... ........................... 89 Alexander Lloyd .. •· . ................... ... 89 Francis C. Sherman. .. .... ·-... 90 Augustus Garrett .. ...... .... 90 John C. Chapin .. • • ti ••• . ...... 91 James Curtiss ..... .. .. .. 91 James H. Woodworth ........................ 91 Walter S. Gurnee ... .. ........... .. 91 Charles M. Gray. .. .............. •· . 92 Isaac L. Milliken .. .. 92 Levi D. Boone .. .. .. ... 92 Thomas Dyer .. .. .. .. 93 John Wentworth .. .. .. .. 93 John C. Haines. .. .. .. .. ... 93 ,Julian Rumsey ................... 94 John B. Rice ... ..................... 94 Roswell B. Mason ..... ...... 94 Joseph Medill .... 95 Lester L. Bond. ....... 96 Harvey D. Colvin -

The Open Court. a WEEKLY Jottenfal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenSIUC The Open Court. A WEEKLY JOTTENfAL DEVOTED TO THE RELIGION OF SCIENCE. 1 Two Dollars No. 307. (Vol. VII.— 28.) CHICAGO, per Year. JULY 13, 1893. Single Copies, Cents. I 5 Copyright by The Open Court Publishing Co.— Reprints are permitted only on condition of giving full credit to Author and Publisher. AN ALIEN'S FOURTH OF JULY. an anarchist-sympathiser, who would substitute the flag red for the American stars and stripes ; a rene- BY HERMANN LIEB. gade ; a traitor ; a rascal ; a scoundrel ; and horresco Until quite recently I thought myself entitled to refereiis an "alien"; "a man without a drop of the denomination of "American," with all the title American blood in his veins." The identical breath implies : not an aborigine of course, but a full-fledged which denounces him as an arrant demagogue pro- citizen of the American Republic, being a devoted ad- nounces him a political corpse ; in other words, a schem- herent to the principles underlying its constitution ing politician committing Jiari-kaii \n\\.\\ " malice afore- and laws, and, having faithfully served the country all thought." through the late war together with 275,000 others of 1 never had much faith in those who boast of their the German tribe to which I owe my origin, I con- American blood, but I do believe in the common sense sidered that title honestly earned. I was about to cele- of the average American which generally asserts itself brate the "glorious Fourth" with my fellow citizens after a short period of bluster I excitement and ; be- at Jackson Park, but having read the sermon of a pious lieve it will do so in the present case. -

The First Defenders Civil War Round Table Newsletter

4 The First Defenders Civil War Round Table Newsletter September 2009 A New Campaign Begins Welcome back to a new season! The programs have been set and promise to impress Round Table members. Mark your calendars now for the 2nd Tuesday of the next 9 months and read on for details... Round Table Business Old Business: On May 12, 2009, President Mike Gabriel called to order the May meeting of the First Defenders Round Table. Dave Fox reported that there were 36 people signed up for the field trip to Frederick with space for 10 more. A report from Roger Cotterill and Dave follows in this newsletter. During the book raffle, it was decided to donate $400 to Richmond, $500 to Monocacy, and $400 to Cedar Creek. The monies were disbursed from the book raffle fund ($700), from the treasury ($500), and from the trip fund ($100). The Election of Officers resulted in the following: President—Joe Schaeffer Vice President—Robert Marks Treasurer—Arlan Christ Membership—Pat Christ Book Raffle/Preservation—Tom Tate Recording Secretary—Richard Kennedy Solicitor—Robert Grim Newsletter—Linda Zeiber Board - at - Large — Dave Fox & Roger Cotterill Program Coordinators—Errol Steffy & Barbara Shafer (Don Stripling will be added if approved by the membership.) New Business: There was a discussion about ordering shirts and hats. The program coordinators would like to give them to speakers who do not receive an honorarium. Further discussion was held during the Board of Directors meeting in June. Richard Kennedy will give more information in his minutes of that meeting. Several trip ideas were talked about for spring of 2010, and it was suggested that we have our own flag for meetings. -

The Open Court

^9 ' The Open Court. A ^VEKKLY .IOLTRNrA.L DEVOTED TO THE RELIGION OF SCIENCE. (Vol. ( Two Dollars per Year. No. 312. VII.—33.) CHICAGO, AUGUST- 17, 1893. Single Copies, i 5 Cents. Copyright by The Open Court Publishing Co. —Reprints are permitted only on condition of giving full credit to Author and Publisher. THE LESSON OF OUR FINANCIAL CRISIS. or even hinted at by any o)ie 0/ the three parties whicli presented pres- ' BY HERMANN LIEB. idential candidates. " The finances of the country are completely de- But a change' from this satisfactory state of affairs " was wrought through slavery agitation and a destruc- moralised ; of course they are, as the logic of events, " tive all its demoralising tendencies. It brought for, if they were not the " eternal law of gravitation! war with the " immutable law of justice! " were unmeaning ejac- forth a complete revolution in the economic manage- ' ' for ulations. There is just as much sense in supposing ment of the country ; the old shibboleth by and the that the natural laws underlying the social organisation people" was set aside and the watchword "by the few " can be violated with impunity, as that an individual, and for the few substituted ; an era of jobbery and carrying on a riotous living, can expect to keep his health of wild speculation in and out of congress was inaug- and to live to a green old age. " It is loss of confi- urated. What the outcome of this condition of things dence," says one searcher for the cause of the prevail- would be was prognosticated by President Lincoln, ing "crisis,"—as the symptoms of social and political who, shortl}' before his death, wrote to a friend : " rottenness are politel}' termed ; -'it is the silver says "Yes, we may congratulate ourselves that this cruel war is another, "it is the fear of a reduction of the tariff," Hearing to a close. -

Swiss in the American Civil War a Forgotten Chapter of Our Military History

Swiss American Historical Society Review Volume 51 Number 3 Article 5 11-2015 Swiss in the American Civil War A Forgotten Chapter of our Military History David Vogelsanger Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review Part of the European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Vogelsanger, David (2015) "Swiss in the American Civil War A Forgotten Chapter of our Military History," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 51 : No. 3 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol51/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swiss American Historical Society Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Vogelsanger: Swiss in the American Civil War A Forgotten Chapter of our Milita Swiss in the American Civil War A Forgotten Chapter of our Military History by David Vogelsanger* In no foreign conflict since the Battle of Marignano in 1515, except Napoleon's Russian campaign, have as many soldiers of Swiss origin fought as in the American War of Secession. It is an undertaking of great merit to rescue this important and little known fact from oblivion and it is a privilege for me to introduce this concise study by my friend Heinrich L. Wirz and his co-author Florian A. Strahm. The Swiss, mostly volunteers, who went to war either to preserve the Union against the secession of the southern States or for the independence of those same States, all risked their lives for an honorable cause. -

Westhoff Book for CD.Pdf (2.743Mb)

Urban Life and Urban Landscape Zane L. Miller, Series Editor Westhoff 3.indb 1 5/14/2007 12:39:31 PM Westhoff 3.indb 2 5/14/2007 12:39:31 PM A Fatal Drifting Apart Democratic Social Knowledge and Chicago Reform Laura M. Westhoff The Ohio State University Press Columbus Westhoff 3.indb 3 5/14/2007 12:39:33 PM Copyright © 2007 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Westhoff, Laura M. A fatal drifting apart : democratic social knowledge and Chicago reform / Laura M. Westhoff. — 1st. ed. p. cm. — (Urban life and urban landscape) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1058-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1058-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9137-5 (cd-rom) ISBN-10: 0-8142-9137-6 (cd-rom) 1. Social reformers—Chicago—Illinois—History. 2. Social ethics—Chicago— Illinois—History. 3. Chicago (Ill.)—Social conditions. 4. United States—Social conditions—1865–1918. I. Title. HN80.C5W47 2007 303.48'40977311—dc22 2006100374 Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Type set in Minion Printed by Thomson-Shore The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Westhoff 3.indb 4 5/14/2007 12:39:33 PM To Darel, Henry, and Jacob Westhoff 3.indb 5 5/14/2007 12:39:33 PM Westhoff 3.indb 6 5/14/2007 12:39:33 PM Contents Preface ix Acknowledgments xiii Introduction 1 Chapter 1. -

Swiss and American Republicanism in the 'Age of Revolution' and Beyond

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2014 A Practical Alternative; Swiss and American Republicanism in the 'Age of Revolution' and Beyond Alexander Gambaccini CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/302 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] A Practical Alternative: Swiss and American Republicanism in the 'Age of Revolution' and Beyond By Alexander Gambaccini Adviser: Professor Gregory Downs Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts of the City College of the City University of New York 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1. Introduction ............................................................................................3 1.1 Background ...........................................................................................3 1.2 Historiographical Overview ................................................................11 1.3 Objectives, Methodology and Presentation ........................................12 Section 2. Daniel-Henri Druey and American Democracy: Lessons in Republican Government ...............................................................................................15 2.1 Introduction .........................................................................................15 -

Economics Prof Is Labor Mediator

North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship NCAT Student Newspapers Digital Collections 11-1949 The Register, 1949-11-00 North Carolina Agricutural and Technical State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.library.ncat.edu/atregister Recommended Citation North Carolina Agricutural and Technical State University, "The Register, 1949-11-00" (1949). NCAT Student Newspapers. 104. https://digital.library.ncat.edu/atregister/104 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collections at Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in NCAT Student Newspapers by an authorized administrator of Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THANKSGIVING LITTLE FOXES' November 24 JH\\t mktt\\%t$x December 1-2 "The Cream of College New$" VOL. XLV—No. 2 A. and T. College, Greensboro, N. C, November, 1949 5 CENTS PER COPY Economics Prof Is Labor Mediator Dr. W.E. Williams Strike Arbitrator in N. C. Homecoming—Founders' Day Exercise Strike Arbitrator Most Elaboration in School's History Nearly 15,000 alumni, former stu Founder's Day, or Dudley Day, is In North Carolina dents, and visitors invaded the A. the annual observance of the college and ZT- 'College campus to take part in honor of the late James B. Dudley, Dr. W. E. Williams, professor of in one of the most colorful and elabo one of the founders of the school. AU Economics at A. and T. College, has rate programs in the history o£ the classes were suspended after 9:50 a. -

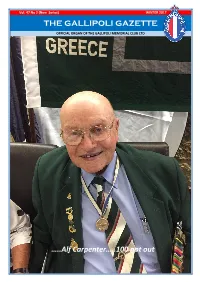

Alf Carpenter…..100 Not Out

Vol. 47 No 2 (New Series) WINTER 2017 THE GALLIPOLI GAZETTE OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE GALLIPOLI MEMORIAL CLUB LTD …..Alf Carpenter…..100 not out 1 EDITORIAL…….. This edition carries a full report on the Gallipoli Art celebration and presented Alf Carpenter with a Prize which again attracted a broad range of entries. certificate of Club Life Membership. We also look at the commemoration of Anzac Day The elevation of John Robertson to Club President at the Club which included the HMAS Hobart at the April Annual Meeting sees the continuity of Association and was highlighted by the 2/4th the strong leadership the Club has benefitted from Australian Infantry Battalion Reunion which over past decades since the Club was lifted out of doubled as celebration of the 100th birthday three financial uncertainty in the early 1990s. "Robbo" days earlier of its Battalion Association President for joined the Committee in 1991 along with outgoing the past 33 years, Alf Carpenter. President Stephen Ware and myself. So, I know first- The numbers at the reunion lunch were bolstered hand of John's strong commitment over many years by the many friends Alf has made among the to the Club and its ideals. The Club also owes a families of his World War Two mates and the massive debt to retiring President Stephen Ware, support he has given to those families as the ranks who has stepped down to be a Committee member of the 2/4th diminished over the years. The new for continuity. Thank you Stephen for your visionary Gallipoli Club President, John Robertson, joined the leadership and prudent financial management over three decades. -

Congressional Record-House. 1183

1910. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. 1183 OHIO. POSTMASTERS. William A. Coble to be postmaster at Delphos, Ohio, in place CALIFORNIA. of William A. Coble. Incumbent's commission expired Decem Obarles W. Beatty, at Maricopa, Cal ber 13, 1908. Salmon H. Loomis, at Kingsburg, Cal. John F. Outcalt to be postmaster at Wauseon, Ohio, in place of John F. Outcalt. Incumbent's commission expires January COLORADO. 31, 1910. William T. Brumbaugh, at Fruita, Colo. OKLAHOMA.. GlOORGIA. Nolia B. Dore to be postmaster at Westville, Okla. Office Willie 0. Goodson, at Union City, Ga. became presidential January 1, 1910. ILLINOIS. PENNSYLVANIA. William G. Baie, at Hinckley, m William W. McClelland to be postmaster at Polk, Pa. Office Harry L. Frier, at Benton, Ill. became presidential July 1, 1909. Peter McDonald, at Cicero (late Hawthorne), Ill. Clayton O. Slater to be postmaster at Latrobe, Pa., in place I James W. Prouty, at Roseville, Ill. of Clayton. 0. Slater. Incumbent's commission expires Febru- IOWA• . ary 1, 1910. • I Isador Sobel to be postmaster at Erie, Pa., in place of Isador Ralph A. Dunkle, at Gilman, Iowa. Sobel. Incumbent's commission expires March 29, 1910. John H. Kolthoff, at New Hampton, Iowa. Starling W. Waters to be postmaster at Warren, Pa., in place MARYLAND. of Starling W. Waters. Incumbent's commission expired Jan Walter R Rudy, at Mount Airy, Md. uary 23, 1910. Charles W. Zook to be postmaster at Roaring Spring, Pa., MINNESOTA. in place of Charles W. Zook. Incumbent's commission expires Dennis F. McGrath, at Barnesville, Minn. February 6, 1910. Henry H. -

The Swiss in the American Civil War 1861-1865

Swiss American Historical Society Review Volume 51 Number 2 Article 2 6-2015 The Swiss in the American Civil War 1861-1865 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review Part of the European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation (2015) "The Swiss in the American Civil War 1861-1865," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 51 : No. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol51/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swiss American Historical Society Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 38 et al.: The SwissThe in Swissthe American in the American Civil War 1861-1865 Civil War 4. Alphabetical List of 106 Swiss Officers with Short Biographical Entries Anderegg, John (Johann) A. (1823- 1910), U.S. first lieutenant • Born 12 June 1823 in Koppigen, Canton Bern • Emigrated to Cincinnati, Ohio • Farmer in Guttenberg, Jefferson Township, Iowa after 1853 • Volunteer in Company D, Twenty-seventh Iowa Regiment 16 August 1862; advanced to second, then first lieutenant; participated in the Battle of Little Rock 10 September 1863 and possibly in the Battle of Memphis, Tennessee; honorable discharge in 1864 due to chronic rheumatic and kidney trouble • Farmer in Guttenberg until 1884, then insurance agent and auctioneer; long-time member and commander of the veteran group of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) • Died 22 May 1910 in Guttenberg and was buried in the town cemetery. -

Foreword a Forgotten Chapter of Our Military History

Swiss American Historical Society Review Volume 51 Number 2 Article 3 6-2015 Foreword A Forgotten Chapter of our Military History David Vogelsanger Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review Part of the European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Vogelsanger, David (2015) "Foreword A Forgotten Chapter of our Military History," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 51 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol51/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swiss American Historical Society Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Vogelsanger: Foreword A Forgotten Chapter of our Military History June 2015 SAHS Review 5 Foreword A Forgotten Chapter of our Military History David Vogelsanger More Swiss participated in the American Civil War than in any other foreign conflict except the Battle of Marignano in 1515 and Napoleon's Russian Campaign of 1812. This work has rescued this important and little-known fact from oblivion, and it is a privilege to introduce this concise study by my friend, Heinrich L. Wirz, and his collaborator, Florian A. Strahm. Mostly as volunteers, the Swiss fought either to maintain the Union, or they risked their lives for the independence of the South. These men believed it was honorable to fight for their new homeland where they had migrated in search of prosperity. Many men fought for the ideals of their respective countries, but relatively few risked their lives either for the abolition of slavery or for its preservation.