Splenomegaly: Investigation, Diagnosis and Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thalassemia and the Spleen

Thalassemia and the Spleen 4 Living with Thalassemia are developing an infection (fever, chills, sore throats, unexplained coughs, listlessness, muscle pain, etc.) and Issues in Thalassemia report them to your doctor right away. Thalassemia Care • Sometimes a splenectomy can lead to an exceptionally and the Spleen high platelet count, which can in turn lead to blood clotting. by Marie B. Martin, RN, and Craig Butler Your doctor should monitor your platelet count on a regular basis and may ask you to take baby aspirin daily. This sounds kind of frightening. Is a splenectomy really a What is the spleen? wise choice? The spleen is a small organ (normally That’s a decision that must be made in each individual case. about the size of a fist) that lies in the A doctor with significant experience with thalassemia is upper left part of the abdomen, near going to be in the best position to offer advice about this; the stomach and below the ribcage. however, most people who are splenectomized are able to What does it do? manage the challenges it presents with relatively little The spleen has a number of functions, the most important of difficulty. which are filtering blood and creating lymphocytes. It also acts as a “reservoir” of blood, keeping a certain amount on Of course, it’s best to avoid any circumstances that can lead hand for use in emergencies. to the need for a splenectomy in the first place. For a person with thalassemia, this means following a transfusion In its filtering capacity, the spleen is able to remove large regimen that keeps hemoglobin levels above 9 or 10gm/dL. -

Osteopathic Approach to the Spleen

Osteopathic approach to the spleen Luc Peeters and Grégoire Lason 1. Introduction the first 3 years to 4 - 6 times the birth size. The position therefore progressively becomes more lateral in place of The spleen is an organ that is all too often neglected in the original epigastric position. The spleen is found pos- the clinic, most likely because conditions of the spleen do tero-latero-superior from the stomach, its arterial supply is not tend to present a defined clinical picture. Furthermore, via the splenic artery and the left gastroepiploic artery it has long been thought that the spleen, like the tonsils, is (Figure 2). The venous drainage is via the splenic vein an organ that is superfluous in the adult. into the portal vein (Figure 2). The spleen is actually the largest lymphoid organ in the body and is implicated within the blood circulation. In the foetus it is an organ involved in haematogenesis while in the adult it produces lymphocytes. The spleen is for the blood what the lymph nodes are for the lymphatic system. The spleen also purifies and filters the blood by removing dead cells and foreign materials out of the circulation The function of red blood cell reserve is also essential for the maintenance of human activity. Osteopaths often identify splenic congestion under the influence of poor diaphragm function. Some of the symptoms that can be associated with dysfunction of the spleen are: Figure 2 – Position and vascularisation of the spleen Anaemia in children Disorders of blood development Gingivitis, painful and bleeding gums Swollen, painful tongue, dysphagia and glossitis Fatigue, hyperirritability and restlessness due to the anaemia Vertigo and tinnitus Frequent colds and infections due to decreased resis- tance Thrombocytosis Tension headaches The spleen is also considered an important organ by the osteopath as it plays a role in the immunity, the reaction of the circulation and oxygen transport during effort as well as in regulation of the blood pressure. -

An 8-Year-Old Boy with Fever, Splenomegaly, and Pancytopenia

An 8-Year-Old Boy With Fever, Splenomegaly, and Pancytopenia Rachel Offenbacher, MD,a,b Brad Rybinski, BS,b Tuhina Joseph, DO, MS,a,b Nora Rahmani, MD,a,b Thomas Boucher, BS,b Daniel A. Weiser, MDa,b An 8-year-old boy with no significant past medical history presented to his abstract pediatrician with 5 days of fever, diffuse abdominal pain, and pallor. The pediatrician referred the patient to the emergency department (ED), out of concern for possible malignancy. Initial vital signs indicated fever, tachypnea, and tachycardia. Physical examination was significant for marked abdominal distension, hepatosplenomegaly, and abdominal tenderness in the right upper and lower quadrants. Initial laboratory studies were notable for pancytopenia as well as an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. aThe Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, New York; and bAlbert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis showed massive splenomegaly. The only significant history of travel was immigration from Dr Offenbacher led the writing of the manuscript, recruited various specialists for writing the Albania 10 months before admission. The patient was admitted to a tertiary manuscript, revised all versions of the manuscript, care children’s hospital and was evaluated by hematology–oncology, and was involved in the care of the patient; infectious disease, genetics, and rheumatology subspecialty teams. Our Mr Rybinski contributed to the writing of the multidisciplinary panel of experts will discuss the evaluation of pancytopenia manuscript and critically revised the manuscript; Dr Joseph contributed to the writing of the manuscript, with apparent multiorgan involvement and the diagnosis and appropriate cared for the patient, and was critically revised all management of a rare disease. -

Atrial Fibrillation and Splenic Infarction Presenting with Unexplained Fever and Persistent Abdominal Pain - a Case Report and Review of the Literature

Case ReportSplenic Infarction Presenting with Unexplained Fever and Persistent Acta Abdominal Cardiol SinPain 2012;28:157-160 Atrial Fibrillation and Splenic Infarction Presenting with Unexplained Fever and Persistent Abdominal Pain - A Case Report and Review of the Literature Cheng-Chun Wei1 and Chiung-Zuan Chiu1,2 Atrial fibrillation is a common clinical problem and may be complicated with events of thromboembolism, especially in patients with valvular heart disease. Splenic infarction is a rare manifestation of the reported cases. The symptoms may vary from asymptomatic to severe peritonitis, though early diagnosis may lessen the probability of severe complications and lead to a good prognosis. We report a 79-year-old man with multiple cardioembolic risk factors who presented with fever and left upper quadrant abdominal pain. To diagnose splenic infarction is challenging for clinicians and requires substantial effort. Early resumption of the anti-coagulation component avoids complications and operation. Key Words: Atrial fibrillation · Splenic infarction · Thromboembolism event · Valvular heart disease INTRODUCTION the patient suffered from severe acute abdominal pain due to splenic infarction. Fortunately, early diagnosis Splenic infarction is a rare cause of an acute abdo- and anticoagulation therapy helped the patient to avoid men. According to a sizeable autopsy series, only 10% emergency surgery and a possible negative outcome. of splenic infarctions had been diagnosed antemortem.1-3 It can occur in a multitude of conditions, with general or local manifestations, and was often a clinical “blind CASE REPORT spot” during the process of diagnosis. However, splenic infarction must be considered in patients with hema- The patient was a 79-year-old man with degenera- tologic diseases or thromboembolic conditions. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

Cells, Tissues and Organs of the Immune System

Immune Cells and Organs Bonnie Hylander, Ph.D. Aug 29, 2014 Dept of Immunology [email protected] Immune system Purpose/function? • First line of defense= epithelial integrity= skin, mucosal surfaces • Defense against pathogens – Inside cells= kill the infected cell (Viruses) – Systemic= kill- Bacteria, Fungi, Parasites • Two phases of response – Handle the acute infection, keep it from spreading – Prevent future infections We didn’t know…. • What triggers innate immunity- • What mediates communication between innate and adaptive immunity- Bruce A. Beutler Jules A. Hoffmann Ralph M. Steinman Jules A. Hoffmann Bruce A. Beutler Ralph M. Steinman 1996 (fruit flies) 1998 (mice) 1973 Discovered receptor proteins that can Discovered dendritic recognize bacteria and other microorganisms cells “the conductors of as they enter the body, and activate the first the immune system”. line of defense in the immune system, known DC’s activate T-cells as innate immunity. The Immune System “Although the lymphoid system consists of various separate tissues and organs, it functions as a single entity. This is mainly because its principal cellular constituents, lymphocytes, are intrinsically mobile and continuously recirculate in large number between the blood and the lymph by way of the secondary lymphoid tissues… where antigens and antigen-presenting cells are selectively localized.” -Masayuki, Nat Rev Immuno. May 2004 Not all who wander are lost….. Tolkien Lord of the Rings …..some are searching Overview of the Immune System Immune System • Cells – Innate response- several cell types – Adaptive (specific) response- lymphocytes • Organs – Primary where lymphocytes develop/mature – Secondary where mature lymphocytes and antigen presenting cells interact to initiate a specific immune response • Circulatory system- blood • Lymphatic system- lymph Cells= Leukocytes= white blood cells Plasma- with anticoagulant Granulocytes Serum- after coagulation 1. -

Terminology Resource File

Terminology Resource File Version 2 July 2012 1 Terminology Resource File This resource file has been compiled and designed by the Northern Assistant Transfusion Practitioner group which was formed in 2008 and who later identified the need for such a file. This resource file is aimed at Assistant Transfusion Practitioners to help them understand the medical terminology and its relevance which they may encounter in the patient’s medical and nursing notes. The resource file will not include all medical complaints or illnesses but will incorporate those which will need to be considered and appreciated if a blood component was to be administered. The authors have taken great care to ensure that the information contained in this document is accurate and up to date. Authors: Jackie Cawthray Carron Fogg Julia Llewellyn Gillian McAnaney Lorna Panter Marsha Whittam Edited by: Denise Watson Document administrator: Janice Robertson ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We would like to acknowledge the following people for providing their valuable feedback on this first edition: Tony Davies Transfusion Liaison Practitioner Rose Gill Transfusion Practitioner Marie Green Transfusion Practitioner Tina Ivel Transfusion Practitioner Terry Perry Transfusion Specialist Janet Ryan Transfusion Practitioner Dr. Hazel Tinegate Consultant Haematologist Reviewed July 2012 Next review due July 2013 Version 2 July 2012 2 Contents Page no. Abbreviation list 6 Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) 7 Acidosis 7 Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (APTT) 7 Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome -

Case Report Gastric Volvulus Due to Splenomegaly - a Rare Entity

Case Report Gastric Volvulus Due to Splenomegaly - A rare Entity. Ashok Mhaske Department of Surgery,People’s College of Medical Sciences and Research Centre, Bhanpur, Bhopal. 462010 , (M.P.) Abstract: Gastric volvulus is a rare condition which typically presents with intermittent episodes of abdominal pain. The volvulus occurs around an axis made by two fixed points, organo-axial or mesentero-axial. Increased pressure within the hernial sac associated with gastric distension can lead to ischemia and perforation. Acute obstruction of a gastric volvulus is thus a surgical emergency.We present an unusual case of gastric volvulus secondary to tropical splenomegaly. Tropical splenomegaly precipitating gastric volvulus is not documented till date. Key Words: Gastric volvulus, Tropical splenomegaly. Introduction: to general practitioner but as symptoms persisted she Gastric volvulus is abnormal rotation of the was referred to our tertiary care centre for expert stomach of more than 180 degrees. It can cause closed opinion and management. loop obstrcution and at times can result in On examination, vital parameters and hydration was adequate with marked tenderness in incarceration and strangulation. Berti first described epigastric region with vague lump. Her routine gastric volvulus in 1866; to date, it remains a rare investigations were inconclusive but she did partially clinical entity. Berg performed the first successful responded to antispasmodic and antacid drugs. operation on a patient with gastric volvulus in 1896. Ultrasound of abdomen and Barium studies Borchardt (1904) described the classic triad of severe revealed gastric volvulus (Fig.1 & 2) with epigastric pain, retching without vomiting and splenomegaly for which she was taken up for inability to pass a nasogastric tube. -

Asplenia Vaccination Guide

Stanford Health Care Vaccination Subcommitee Revision date 11/308/2018 Functional or Anatomical Asplenia Vaccine Guide I. PURPOSE To outline appropriate vaccines targeting encapsulated bacteria for functionally or anatomically asplenic patients. Routine vaccines that may also be indicated but not addressed here include influenza, Tdap, herpes zoster, HPV, MMR, and varicella.1,2,3 II. Background Functionally or anatomically asplenic patients should be vaccinated to decrease the risk of sepsis due to organisms such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type B, and Neisseria meningitidis. Guidelines are based on CDC recommendations. For additional information, see https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/imz/adult-conditions.html. III. Procedures/Guidelines1,2,3,6,7,8 The regimen consists of 4 vaccines initially, followed by repeat doses as specified: 1. Haemophilus b conjugate (Hib) vaccine (ACTHIB®) IM once if they have not previously received Hib vaccine 2. Pneumococcal conjugate 13-valent (PCV13) vaccine (PREVNAR 13®) IM once • 2nd dose: Pneumococcal polysaccharide 23-valent (PPSV23) vaccine (PNEUMOVAX 23®) SQ/IM once given ≥ 8 weeks later, then 3rd dose as PPSV23 > 5 years later.4 Note: The above is valid for those who have not received any pneumococcal vaccines previously, or those with unknown vaccination history. If already received prior doses of PPSV23: give PCV13 at least 1 year after last PPSV23 dose. 3. Meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY-CRM, MENVEO®) IM (repeat in ≥ 8 weeks, then every 5 years thereafter) 4. Meningococcal serogroup B vaccine (MenB, BEXSERO®) IM (repeat in ≥ 4 weeks) Timing of vaccination relative to splenectomy: 1. Should be given at least 14 days before splenectomy, if possible. -

Peripheral Blood Cells Changes After Two Groups of Splenectomy And

ns erte ion p : O y p H e f Yunfu et al., J Hypertens (Los Angel) 2018, 7:1 n o l A a DOI: 10.4172/2167-1095.1000249 c c n r e u s o s J Journal of Hypertension: Open Access ISSN: 2167-1095 Research Article Open Access Peripheral Blood Cells Changes After Two Groups of Splenectomy and Prevention and Treatment of Postoperative Complication Yunfu Lv1*, Xiaoguang Gong1, XiaoYu Han1, Jie Deng1 and Yejuan Li2 1Department of General Surgery, Hainan Provincial People's Hospital, Haikou, China 2Department of Reproductive, Maternal and Child Care of Hainan Province, Haikou, China *Corresponding author: Yunfu Lv, Department of General Surgery, Hainan Provincial People's Hospital, Haikou 570311, China, Tel: 86-898-66528115; E-mail: [email protected] Received Date: January 31, 2018; Accepted Date: March 12, 2018; Published Date: March 15, 2018 Copyright: © 2018 Lv Y, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Objective: This study aimed to investigate the changes in peripheral blood cells after two groups of splenectomy in patients with traumatic rupture of the spleen and portal hypertension group, as well as causes and prevention and treatment of splenectomy related portal vein thrombosis. Methods: Clinical data from 109 patients with traumatic rupture of the spleen who underwent splenectomy in our hospital from January 2001 to August 2015 were retrospectively analyzed, and compared with those from 240 patients with splenomegaly due to cirrhotic portal hypertension who underwent splenectomy over the same period. -

Open Splenectomy Scott F

Open Splenectomy Scott F. Gallagher, Larry C. Carey, Michel M. Murr Indications and Contraindications Indications ■ Trauma ■ Blood dyscrasias, e.g., idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura ■ Symptomatic relief, e.g., Gaucher’s disease, chronic myeloid or lymphatic leukemia ■ Splenic cysts and tumors Contraindications ■ No absolute contraindications for splenectomy ■ Limited life expectancy and prohibitive operative risk Contraindications to ■ Previous open upper abdominal surgery Laparoscopic Splenectomy ■ Uncontrolled coagulation disorder ■ Very low platelet count (<20,000/100ml) ■ Massive splenic enlargement, i.e., spleen greater four times normal size or larger ■ Portal hypertension Preoperative Investigation and Preparation ■ Imaging studies to estimate the size of the spleen or extent of splenic injury and other abdominal injuries in trauma cases ■ Interpretation of bone marrow biopsy, peripheral blood smear, and ferrokinetics in coordination with a hematologist ■ Discontinue anticoagulants (such as aspirin, warfarin, clopidogrel and vitamin E) ■ Patients routinely given polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine, Haemophilus influenzae b conjugate vaccines and meningococcal vaccines on the same day at least 10–14days prior to splenectomy (given postoperatively in trauma cases) ■ Prophylactic antibiotics (cefazolin or cefotetan) ■ Perioperative DVT prophylaxis ■ Perioperative steroids should be administered to patients on long-term steroid therapy 954 SECTION 7 Spleen Procedure STEP 1 The standard supine position is employed with an optional small roll/bump under the left flank. The patient should be well secured to the operating table should it become necessary to tilt the table to improve visualization of the operative field. Mechanical retractors greatly enhance exposure and the primary surgeon should stand on the right side of the patient; the first assistant opposite the surgeon on the left side of the patient. -

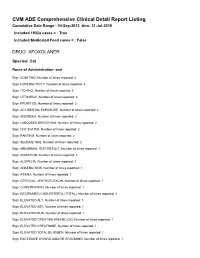

FDA CVM Comprehensive ADE Report Listing for Afoxolaner

CVM ADE Comprehensive Clinical Detail Report Listing Cumulative Date Range : 04-Sep-2013 -thru- 31-Jul-2018 Included 1932a cases = : True Included Medicated Feed cases = : False DRUG: AFOXOLANER Species: Cat Route of Administration: oral Sign: VOMITING, Number of times reported: 4 Sign: HYPERACTIVITY, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: ITCHING, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: LETHARGY, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: PRURITUS, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: ACCIDENTAL EXPOSURE, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: ANOREXIA, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: LABOURED BREATHING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: NOT EATING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: PANTING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: SEIZURE NOS, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: ABNORMAL TEST RESULT, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: AGITATION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ALOPECIA, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ANAEMIA NOS, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ATAXIA, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: CERVICAL VENTROFLEXION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: CONSTIPATION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: DECREASED CHOLESTEROL (TOTAL), Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED ALT, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED AST, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED BUN, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED CREATINE-KINASE (CK), Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED CREATININE, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED TOTAL BILIRUBIN, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: EXCESSIVE LICKING AND/OR GROOMING, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: FEVER,