Kudos for Jennifer Buchanan and TUNE IN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of Musical Rhythm on Cardiovascular, Respiratory, And

The Influence of Musical Rhythm on Cardiovascular, Respiratory, and Electrodermal Activity Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt der Philosophischen Fakult¨at der Martin-Luther-Universit¨at Halle-Wittenberg, Institut f¨ur Musik, Abteilung Musikwissenschaft von Martin Morgenstern geboren am 3. Juni 1979 in Dresden Gutachter: Professor Dr. Wolfgang Auhagen Martin-Luther-Universit¨at, Halle-Wittenberg Professor Dr. med. Hans-Christian Jabusch Hochschule f¨ur Musik Carl Maria von Weber, Dresden Tag der Verteidigung: 7. Juli 2009 iii Abstract Background. Athanasius Kircher, one of the first prominent figures to pro- pose a connection between the distinct rhythm of the heart and the state of people’s health, suggested the use of rhythmic stimuli to cure diseases. Since then, there have been various attempts to alter the heart rate by means of auditory stimuli, and for similar purposes. Be it in music or in rhythmical coordination tasks, interactions of periodic exogenous pulses and endogenous biological rhythms have been studied extensively. However, there are still limitations to understanding the regulating mechanisms in cardio-respiratory synchronisation. Aims. Various listening and bio-feedback experiments are discussed, dealing with different aspects of the influence of rhythmical auditory stimuli on cardio-respiratory regulation, biological rhythm generation and coordina- tion. A focus is on the interpretation of respective physiological adaptation processes and different relaxation strategies that might help musicians to deal with unwanted stress before, during, and after a musical performance. Dif- ferent challenges inherent to empirical musicological and music-related bio- medical research, and how they might be tackled in future experiments, are considered. -

Music Interventions in Health Care White Paper H C Are in Healt I Nterventions Music 1

MUSIC INTERVENTIONS IN HEALTH CARE WHITE PAPER ARE C H NTERVENTIONS IN HEALT NTERVENTIONS I MUSIC MUSIC 1 BY LINE GEBAUER AND PETER VUUST - IN COLLABORATION WITH WIDEX, SOUNDFOCUS, DKSYSTEMS, AARHUS UNIVERSITY AND DANISH SOUND INNOVATION NETWORK PUBLISHER ABOUT THE PUBLICATION DANISH SOUND INNOVATION NETWORK This publication and possible comments and discussions can be Technical University of Denmark downloaded from www.danishsound.org. Matematiktorvet, Building 303B 2800 Kongens Lyngby The content of this publication reflects the authors’ point of view Denmark and not necessarily the view of the Danish Sound Innovation T +45 45253411 Network as such. W www.danishsound.org Copyright of the publication belongs to the authors. Possible agree- FEBRUARY 2014 ments between the authors might regulate the copyright in detail. ABOUT THE AUTHORS PROF. PETER VUUST is a unique combination of a world class musician and a top-level scientist. Based on his distinguished music and research career, he was appointed professor at The Royal Academy of Music Aarhus (RAMA) in 2008. Peter Vuust has since 2007 led the multidisciplinary research group Music in the Brain, at CFIN Aarhus University Hospital, which aims at understanding the neural processing of music, by using a combination of advanced music theory, behavioural experience, and state-of-the-art brain scanning methods. DR LINE GEBAUER holds an MA in Psychology and a PhD in Neuroscience from Aarhus University. She is currently a postdoctoral fellow in Prof. Peter Vuust’s Music in the Brain research group. Line is studying the neurobiological correlates of 2 music perception, in particular music-induced emotions and pleasure in healthy individuals and in people with developmental WHITE disorders. -

Chapter 7 the Neuroscience of Emotion in Music Jaak Panksepp and Colwyn Trevarthen

07-Malloch-Chap07 9/9/08 10:41 AM Page 105 Chapter 7 The neuroscience of emotion in music Jaak Panksepp and Colwyn Trevarthen 7.1 Overture: why humans move, and communicate, in musical–emotional ways Music moves us. Its rhythms can make our bodies dance and its tones and melodies can stir emotions. It brings life to solitary thoughts and memories, can comfort and relieve loneliness, promote private or shared happiness, and engender feelings of deep sadness and loss. The sounds of music communicate emotions vividly in ways beyond the ability of words and most other forms of art. It can draw us together in affectionate intimacy, as in the first prosodic song-like conversations between mothers and infants. It can carry the volatile emotions of human attach- ments and disputes in folk songs and grand opera, and excite the passions of crowds on great social occasions. These facts challenge contemporary cognitive and neural sciences. The psychobiology of music invites neuroscientists who study the emotional brain to unravel the neural nature of affective experience, and to seek entirely new visions of how the mind generates learning and memory— to reveal the nature of ‘meaning’. The science of communicative musicality—the dynamic forms and functions of bodily and vocal gestures—helps us enquire how the motivating impulses of music can tell compelling stories. This also leads us to ask how human music relates to our animal emotional heritage and the dynamic instinctual movements that communicate emotions. Research on the emotional systems of animals is bringing us closer to explanations of the still mysterious aspects of human affective experiences, and hence the emotional power of music. -

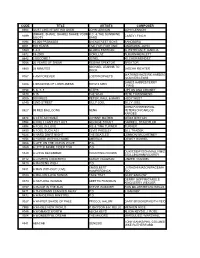

Code Title Artists Composer 8664 (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon John Lennon (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake Your K.C

CODE TITLE ARTISTS COMPOSER 8664 (JUST LIKE) STARTING OVER JOHN LENNON JOHN LENNON (SHAKE, SHAKE, SHAKE) SHAKE YOUR K.C. & THE SUNSHINE 8699 CASEY / FINCH BOOTY BAND 8094 10,000 PROMISES BACKSTREET BOYS SANDBERG 8001 100 YEARS FIVE FOR FIGHTING ONDRASIK, JOHN 8563 1-2-3 GLORIA ESTEFAN G. ESTEFAN/ E. GARCIA 8572 19-2000 GORILLAZ ALBARN/HEWLETT 8642 2 BECOME 1 JEWEL KILCHER/MENDEZ 9058 20 YEARS OF SNOW REGINA SPEKTOR SPEKTOR MICHAEL LEARNS TO 8865 25 MINUTES JASCHA RICHTER ROCK WATKINS/GAZE/RICHARDSO 8767 4 AM FOREVER LOSTPROPHETS N/OLIVER/LEWIS JAMES HARRIS/TERRY 8208 4 SEASONS OF LONELINESS BOYZ II MEN LEWIS 9154 5, 6, 7, 8 STEPS LIPTON AND CROSBY 9370 5:15 THE WHO PETE TOWNSHEND 9005 500 MILES PETER, PAUL & MARY HEDY WEST 8140 52ND STREET BILLY JOEL BILLY JOEL JOEM FAHRENKROG- 8927 99 RED BALLOONS NENA PETERSON/CARLOS KARGES 8674 A CERTAIN SMILE JOHNNY MATHIS WEBSTER/FAIN 8554 A FIRE I CAN'T PUT OUT GEORGE STRAIT DARRELL STAEDTLER 8594 A FOOL IN LOVE IKE & TINA TURNER TURNER 8455 A FOOL SUCH AS I ELVIS PRESLEY BILL TRADER 9224 A HARD DAY'S NIGHT THE BEATLES LENNON/ MCCARTNEY 8054 A HORSE WITH NO NAME AMERICA DEWEY BUNNEL 9468 A LIFE ON THE OCEAN WAVE P.D. 9469 A LITTLE MORE CIDER TOO P.D. DURITZ/BRYSON/MALLY/MIZ 8320 A LONG DECEMBER COUNTING CROWS E/GILLINGHAM/VICKREY 9112 A LOVER'S CONCERTO SARAH VAUGHAN LINZER / RANDEL 9470 A MAIDENS WISH P.D. ENGELBERT LIVRAGHI/MASON/PACE/MA 8481 A MAN WITHOUT LOVE HUMPERDINCK RIO 9183 A MILLION LOVE SONGS TAKE THAT GARY BARLOW GERRY GOFFIN/CAROLE 8073 A NATURAL WOMAN ARETHA FRANKLIN KING/JERRY WEXLER 9157 A PLACE IN THE SUN STEVIE WONDER RON MILLER/BRYAN WELLS 9471 A THOUSAND LEAGUES AWAY P.D. -

MUSIK MACHT GEISTIG FIT.Pdf

Studium generale © Herausgeber: B. Fischer, 77736 Zell a.H, Birkenweg 19 Tel: 07835-548070 www.wisiomed.de Musik und geistige Leistungsfähigkeit Herausgeber: Prof. Dr. med. Bernd Fischer Musik macht geistig fit „Wer Musikschulen schließt, gefährdet die innere Sicherheit“ (Nida-Rümelin,.2005) in Kooperation mit der Memory-Liga e. V. Zell a. H. sowie dem Verband der Gehirntrainer Deutschlands VGD® und Wissiomed® Akademie Haslach (www.wissiomed.de) Die Unterlagen dürfen in jeder Weise in unveränderter Form unter Angabe des Herausgebers in nicht kommerzieller Weise verwendet werden! Wir sind dankbar für Veränderungsvorschläge, Erweiterungen, Anregungen und Korrekturen, die sie uns jederzeit unter [email protected] zukommen lassen können. © Herausgeber: B. Fischer, 77736 Zell a.H, Birkenweg 19 Tel: 07835-548070 www.wisiomed.de Musik und geistige Leistungsfähigkeit Gliederung Herausgeber, Mitarbeiterinnen 8 Einleitung 9 Musik und Hirndurchblutung 31 Musik und Hirndurchblutung linkes Gehirn 33 Musik und Hirndurchblutung rechtes Gehirn 36 Musik und Hirnstoffwechsel 38 Musik und neurophysiologische Veränderungen 42 Musik und Immunlage 43 Musik und gewebliche Veränderungen im Gehirn 46 Musik und geistige Leistungsfähigkeit 55 Musik, Emotion und emotionale Intelligenz 55 Musik fördert die Aufmerksamkeit 62 2 © Herausgeber: B. Fischer, 77736 Zell a.H, Birkenweg 19 Tel: 07835-548070 www.wisiomed.de Musik und geistige Leistungsfähigkeit Musik fördert die Wahrnehmung 66 Musik und Arbeitsgedächtnis 68 Musik und Langzeitgedächtnis 69 Musik als Rhythmusgeber I 73 Funktionen des präfrontalen Kortex 78 Musik als Rhythmusgeber II 83 Musik und Symmetrieverbesserung des Gehirns 86 Musik und Synchronisation von Atmung und Kreislauf 87 Musik und aktuelle geistige Leistungsfähigkeit 90 Musikerziehung und geistige Leistungsfähigkeit in Bezug auf allgemeine Intelligenz, Rechnen, abstraktes Denken, Kreativität, Emotion, soziale Kompetenz, schulische Erfolge incl. -

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - Updated April 9, 2006

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - updated April 9, 2006 compiled by Linda Bangert Please send any additions or corrections to Linda Bangert ([email protected]) and notice of any broken links to Neil Ottenstein ([email protected]). This listing of tour dates, set lists, opening acts, additional musicians was derived from many sources, as noted on each file. Of particular help were "Higher and Higher" magazine and their website at www.moodies- magazine.com and the Moody Blues Official Fan Club (OFC) Newsletters. For a complete listing of people who contributed, click here. Particular thanks go to Neil Ottenstein, who hosts these pages, and to Bob Hardy, who helped me get these pages converted to html. One-off live performances, either of the band as a whole or of individual members, are not included in this listing, but generally can be found in the Moody Blues FAQ in Section 8.7 - What guest appearances have the band members made on albums, television, concerts, music videos or print media? under the sub-headings of "Visual Appearances" or "Charity Appearances". The current version of the FAQ can be found at www.toadmail.com/~notten/FAQ-TOC.htm I've construed "additional musicians" to be those who played on stage in addition to the members of the Moody Blues. Although Patrick Moraz was legally determined to be a contract player, and not a member of the Moody Blues, I have omitted him from the listing of additional musicians for brevity. Moraz toured with the Moody Blues from 1978 through 1990. From 1965-1966 The Moody Blues were Denny Laine, Clint Warwick, Mike Pinder, Ray Thomas and Graeme Edge, although Warwick left the band sometime in 1966 and was briefly replaced with Rod Clarke. -

The Motivational Qualities and Effects of Music

CHARACTERISTICS AND EFFECTS OF MOTIVATIONAL MUSIC IN EXERCISE A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by David-Lee Priest Department of Sport Sciences, Brunel University July 2003 i ABSTRACT The research programme had three principal objectives. First, the evaluation and extension of the extant conceptual framework pertaining to motivational music in exercise settings. Second, the development of a valid instrument for assessing the motivational qualities of music: The Brunel Music Rating Inventory-2 (BMRI-2). Third, to test the effects of motivational and oudeterous (lacking in both motivational and de-motivational qualities) music in an externally-valid setting. These objectives were addressed through 4 studies. First, a series of open-ended interviews were conducted with exercise leaders and participants (N = 13), in order to investigate the characteristics and effects of motivational music in the exercise setting. The data were content analysed to abstract thematic categories of response. These categories were subsequently evaluated in the context of relevant conceptual frameworks. Subsequently, a sample of 532 health-club members responded to a questionnaire that was designed to assess the perceived characteristics of motivational music. The responses were analysed across age groups, gender, frequency of attendance (low, medium, high), and time of attendance (morning, afternoon, evening). The BMRI-2 was developed in order to address psychometric weaknesses that were associated with its forbear, the BMRI. A refined item pool was created which yielded an 8-item instrument that was subjected to confirmatory factor analysis. A single-factor model demonstrated acceptable fit indices across three different pieces of music, two samples of exercise participants, and both sexes. -

Musiquence – Design, Implementation and Validation of a Customizable Music and Reminiscence Cognitive Stimulation Platform for People with Dementia

Luís Duarte Andrade Ferreira Licenciado em Design de Media Interativos Musiquence – Design, Implementation and Validation of a Customizable Music and Reminiscence Cognitive Stimulation Platform for People with Dementia Dissertação para obtenção do Grau de Doutor em Media Digitais Orientador: Doutor Sergi Bermúdez i Badia, Professor Associado, Faculdade de Ciências Exatas e da Engenharia da Universidade da Madeira Co-orientador: Doutora Sofia Carmen Faria Maia Cavaco, Professora Auxiliar, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade Nova de Lisboa Júri: Presidente: Doutor Nuno Manuel Robalo Correia, Professor Catedrático, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade Nova de Lisboa Arguente(s): Doutor António Fernando Vasconcelos Cunha Castro Coelho, Professor Associado com Agregação, Faculdade de Engenharia da Universidade do Porto Doutor Rui Filipe Fernandes Prada, Professor Associado, Instituto Superior Técnico da Universidade do Porto Vogal(ais): Doutor Dennis Reidsma, Professor Associado, University of Twente Doutor Roberto Llorens Rodríguez, Professor Auxiliar da Universitat Politècnica de Valencia Doutor Sergi Bermúdez i Badia, Professor Associado, Faculdade de Ciências Exatas e da Engenharia da Universidade da Madeira Doutora Teresa Isabel Lopes Romão, Professora Associada, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade Nova de Lisboa Junho 2020 Doctoral Dissertation Title | Musiquence - Design, Implementation and Validation of a Customizable Music and Reminiscence Cognitive Stimulation Platform for People with Dementia. -

Pre-Owned 1970S Sheet Music

Pre-owned 1970s Sheet Music 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING FOR A GUIDE TO CONDITION AND PRICES PER TITLE ex No marks or deterioration Priced £15. good As appropriate for age of the manuscript. Slight marks on front cover (shop stamp or owner's name). Possible slight marking (pencil) inside.Priced £12. fair Some damage such as edging tears. Reasonable for age of manuscript. Priced £5 Album Contains several songs and photographs of the artist(s). Priced £15+ condition considered. Year Year of print.Usually the same year as copyright (c) but not always. Photo Artist(s) photograph on front cover. n/a No artist photo on front cover LOOKING FOR THESE ARTISTS?You’ve come to the right place for The Bee Gees, Eric Clapton, Russ Conway, John B.Sebastian, Status Quo or even Wings or “Woodstock”. Just look for the artist’s name on the lists below. 1970s TITLE WRITER & COMPOSER CONDITION PHOTO YEAR $7,000 and you Hugo & Luigi/George David Weiss ex The Stylistics 1977 ABBA – greatest hits Album of 19 songs from ex Abba © 1992 B.Andersson/B.Ulvaeus After midnight John J.Cale ex Eric Clapton 1970 After the goldrush Neil Young ex Prelude 1970 Again and again Richard Parfitt/Jackie Lynton/Andy good Status Quo 1978 Bown Ain‟t no love John Carter/Gill Shakespeare ex Tom Jones 1975 Airport Andy McMaster ex The Motors 1976 Albertross Peter Green fair Fleetwood Mac 1970 Albertross (piano solo) Peter Green ex n/a ©1970 All around my hat Hart/Prior/Knight/Johnson/Kemp ex Steeleye Span 1975 All creatures great and Johnny -

A Meta-Analytic Review and Field Studies of Ultra-Distance Athletes

Running head: EFFECTS OF SYNCHRONOUS MUSIC Effects of Synchronous Music in Sport and Exercise: A Meta-Analytic Review and Field Studies of Ultra-Distance Athletes A Dissertation submitted by Michelle Louise Curran GCertCrimAnlys BCCJ Griffith GCertTT&L BSc(Psych)(Hons) USQ For the award of Doctor of Philosophy October 2012 EFFECTS OF SYNCHRONOUS MUSIC ii Abstract Effects of music in sport and exercise have been investigated in many forms since the first published study by Ayers (1911). Music has been shown to provide significant benefits to physical and psychological responses but whether such benefits apply to ultra-distance athletes is unknown. The present research quantified effects of music in sport and exercise, specifically in terms of performance, psychological responses, physiological functioning and ratings of perceived exertion (RPE); and also investigated such effects among ultra-distance athletes in training and race environments. Study 1 was a meta-analysis of published research evidence, which quantified effects of music on performance, feelings (Feeling Scale - FS), heart rate (HR), oxygen utilisation (VO 2), and RPE. A total of 86 studies producing 162 effects showed weighted mean effects of d = .35 (performance), d = .47 (FS), d = .14 (HR), d = .25 (VO 2), and d = .29 (RPE) confirming small to moderate benefits of music. In Study 2, two elite ultra-distance athletes completed a 20 km training session on four occasions listening to synchronous motivational music, synchronous neutral music, an audio book, or no music. Motivational music provided athletes with significant benefits compared to no music and audio book conditions. Neutral music was associated with the slowest completion times for Athlete 1 but the second fastest for Athlete 2, behind motivational music. -

The Effects of Stressed Tempo Music on Performance Times of Track Athletes Jennifer Robin Brown

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 The Effects of Stressed Tempo Music on Performance Times of Track Athletes Jennifer Robin Brown Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC THE EFFECTS OF STRESSED TEMPO MUSIC ON PERFORMANCE TIMES OF TRACK ATHLETES BY JENNIFER ROBIN BROWN A Thesis submitted to the Department of Music in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Jennifer Robin Brown on December 9, 2004. _______________________ Jayne M. Standley Professor Directing Thesis _______________________ Clifford K. Madsen Committee Member _______________________ Dianne Gregory Committee Member Approved: ________________________________________ Name of Dean, Dean, School of Music The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named Committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables…………………………………………………………………… iv Abstract………………………………………………………………………… v CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………….. 1 CHAPTER 2 REVIEW OF LITERATURE………….………………………………. 2 Purpose CHAPTER 3 Experimental Method……………………………………………………. 18 Subjects Setting Design Procedure Equipment Data Collection CHAPTER 4 Results…………………………………………………………………….. 24 CHAPTER 5 Discussion…………………………………………………………………. 28 APPENDIX A………………………………………………………….…….. 31 APPENDIX B………………………………………………….……………. -

Ella Fitzgerald Collection of Sheet Music, 1897-1991

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2p300477 No online items Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet music, 1897-1991 Finding aid prepared by Rebecca Bucher, Melissa Haley, Doug Johnson, 2015; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet PASC-M 135 1 music, 1897-1991 Title: Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet music Collection number: PASC-M 135 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 13.0 linear ft.(32 flat boxes and 1 1/2 document boxes) Date (inclusive): 1897-1991 Abstract: This collection consists of primarily of published sheet music collected by singer Ella Fitzgerald. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. creator: Fitzgerald, Ella Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright.