The Last Journey of the San Bao Eunuch Admiral Zheng He” Authored by Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

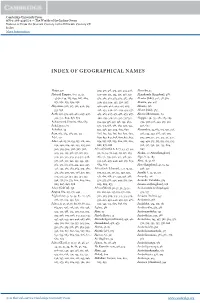

Index of Geographical Names

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42465-3 — The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Volume 2: From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE Index More Information INDEX OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Abaya, 571 309, 317, 318, 319, 320, 323, 328, Akumbu, 54 Abbasid Empire, 6–7, 12, 17, 329–370, 371, 374, 375, 376, 377, Alamkonda (kingdom), 488 45–70, 149, 185, 639, 667, 669, 379, 380, 382, 383, 384, 385, 389, Alaotra (lake), 401, 411, 582 671, 672, 673, 674, 676 390, 393, 394, 395, 396, 397, Alasora, 414, 427 Abyssinia, 306, 317, 322, 490, 519, 400, 401, 402, 409, 415, 425, Albania, 516 533, 656 426, 434, 440, 441, 449, 454, 457, Albert (lake), 365 Aceh, 198, 374, 425, 460, 497, 498, 463, 465, 467, 471, 478, 479, 487, Alborz Mountains, 69 503, 574, 609, 678, 679 490, 493, 519, 521, 534, 535–552, Aleppo, 149, 175, 281, 285, 293, Achaemenid Empire, 660, 665 554, 555, 556, 557, 558, 559, 569, 294, 307, 326, 443, 519, 522, Achalapura, 80 570, 575, 586, 588, 589, 590, 591, 528, 607 Achsiket, 49 592, 596, 597, 599, 603, 607, Alexandria, 53, 162, 175, 197, 208, Acre, 163, 284, 285, 311, 312 608, 611, 612, 615, 617, 620, 629, 216, 234, 247, 286, 298, 301, Adal, 451 630, 637, 647, 648, 649, 652, 653, 307, 309, 311, 312, 313, 315, 322, Aden, 46, 65, 70, 133, 157, 216, 220, 654, 657, 658, 659, 660, 661, 662, 443, 450, 515, 517, 519, 523, 525, 230, 240, 284, 291, 293, 295, 301, 668, 678, 688 526, 527, 530, 532, 533, 604, 302, 303, 304, 306, 307, 308, Africa (North), 6, 8, 17, 43, 47, 49, 607 309, 313, 315, 316, 317, 318, 319, 50, 52, 54, 70, 149, 151, 158, -

Read Doc > Chinese Eunuchs

3UNUDC97OVXW ^ eBook ~ Chinese eunuchs Ch inese eunuch s Filesize: 4.76 MB Reviews Completely one of the better pdf I have got possibly go through. I really could comprehended every little thing using this composed e ebook. It is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding, once you begin to read the book. (Torey Kreiger) DISCLAIMER | DMCA LUJEOEZXBKF0 // PDF > Chinese eunuchs CHINESE EUNUCHS Reference Series Books LLC Apr 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 256x192x8 mm. This item is printed on demand - Print on Demand Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 42. Chapters: Han Dynasty eunuchs, Ming Dynasty eunuchs, Tang Dynasty eunuchs, Zheng He, Sima Qian, Cai Lun, Gao Lishi, Tian Lingzi, Qiu Shiliang, Yang Fugong, Li Fuguo, Tutu Chengcui, Yu Chao'en, Wang Shoucheng, Yishiha, Yang Fuguang, Cheng Yuanzhen, Tong Guan, Zhao Gao, Hong Bao, Zong Ai, Zhu Jingmei, Gang Bing, Liu Jin, Sun Cheng, Huang Hao, Zheng Zhong, Nguyen An, Zhou Man, Wei Zhongxian, Wang Jinghong, Li Lianying, Sun Yaoting, Wang Zhen, Zuo Feng, Eight Tigers. Excerpt: Zheng He (1371-1435, ¿¿ / ¿¿; pinyin: Zhèng Hé), also known as Ma Sanbao (¿¿¿ / ¿¿¿) and Hajji Mahmud Shamsuddin (Persian: ¿¿¿¿ ¿¿¿¿¿ ¿¿¿) was a Muslim Hui-Chinese mariner, explorer, diplomat and fleet admiral, who commanded voyages to Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and East Africa, collectively referred to as the Voyages of Zheng He or Voyages of Cheng Ho from 1405 to 1433. The route of the 7th voyage of Zheng He's fleet. Solid line: main fleet; dashed line: a possible route of Hong Bao's squadron; dotted line: a trip of seven Chinese sailors, including Ma Huan, from Calicut to Mecca on a native ship. -

Zheng He and the Confucius Institute

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 3-2018 The Admiral's Carrot and Stick: Zheng He and the Confucius Institute Peter Weisser Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Weisser, Peter, "The Admiral's Carrot and Stick: Zheng He and the Confucius Institute" (2018). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 625. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/625 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ADMIRAL’S CARROT AND STICK: ZHENG HE AND THE CONFUCIUS INSTITIUTE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Science by Peter Eli Weisser March 2018 THE ADMIRAL’S CARROT AND STICK: ZHENG HE AND THE CONFUCIUS INSTITIUTE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Peter Eli Weisser March 2018 Approved by: Jeremy Murray, Committee Chair, History Jose Munoz, Committee Member ©2018 Peter Eli Weisser ABSTRACT As the People’s Republic of China begins to accumulate influence on the international stage through strategic usage of soft power, the history and application of soft power throughout the history of China will be important to future scholars of the politics of Beijing. -

Chinese Foreign Aromatics Importation

CHINESE FOREIGN AROMATICS IMPORTATION FROM THE 2ND CENTURY BCE TO THE 10TH CENTURY CE Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with research distinction in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University. by Shiyong Lu The Ohio State University April 2019 Project Advisor: Professor Scott Levi, Department of History 1 Introduction Trade served as a major form of communication between ancient civilizations. Goods as well as religions, art, technology and all kinds of knowledge were exchanged throughout trade routes. Chinese scholars traditionally attribute the beginning of foreign trade in China to Zhang Qian, the greatest second century Chinese diplomat who gave China access to Central Asia and the world. Trade routes on land between China and the West, later known as the Silk Road, have remained a popular topic among historians ever since. In recent years, new archaeological evidences show that merchants in Southern China started to trade with foreign countries through sea routes long before Zhang Qian’s mission, which raises scholars’ interests in Maritime Silk Road. Whether doing research on land trade or on maritime trade, few scholars concentrate on the role of imported aromatics in Chinese trade, which can be explained by several reasons. First, unlike porcelains or jewelry, aromatics are not durable. They were typically consumed by being burned or used in medicine, perfume, cooking, etc. They might have been buried in tombs, but as organic matters they are hard to preserve. Lack of physical evidence not only leads scholars to generally ignore aromatics, but also makes it difficult for those who want to do further research. -

6 Bibliography 10/9/02 1:31 Pm Page 477

6 Bibliography 10/9/02 1:31 pm Page 477 1 2 3 SELECT 4 5 BIBLIOGRAPHY 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 477 6 Bibliography 10/9/02 1:31 pm Page 478 BIBLIOGRAPHY 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 478 6 Bibliography 10/9/02 1:31 pm Page 479 SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY Chapters 1: The Emperor’s Grand Plan and 2: A Thunderbolt Strikes 1 2 Abru, Hafiz (trs. K.M. Maitra), A Persian Embassy to China. Lahore, 1934. 3 Battuta, Ibn (trs. S. Lee), The Travels of Ibn Battuta. 1829. Bonavia, J., Collins Illustrated Guide to The Silk Road. The Guide Book Co. Ltd, Hong 4 Kong, 1988. 5 Boulnois, L. (trs. D. Chamberlin), The Silk Road. Allen & Unwin, 1966. Braudel, F. (trs. R. Mayne), A History of Civilizations. Penguin, 1994. 6 Chaudhuri, K.N., ‘A Note on Ibn Taghri Birdi’s description of Chinese Ships in Aden 7 and Jeddah’. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, no. 1, 1989, 112. 8 —— Trade and Civilisation in the Indian Ocean. Cambridge University Press, 1985. Dreyer, E.L., Early Ming China: A Political History 1355–1435. California, Stanford 9 University Press, 1982. 10 Dunn, R.E., The Adventures of Ibn Battuta a Muslim Traveller of the 14th Century. -

Food and Environment in Early and Medieval China

22770 Anderson_FoodEnvironmentChina_FM.indd 6 4/18/14 10:08 AM 22770 Food and Environment in Early and Medieval China Anderson_FoodEnvironmentChina_FM.indd 1 4/18/14 10:08 AM 22770 ENCOUNTERS WITH ASIA Victor H. Mair, Series Editor Encounters with Asia is an interdisciplinary series dedicated to the exploration of all the major regions and cultures of this vast continent. Its timeframe extends from the prehistoric to the contemporary; its geographic scope ranges from the Urals and the Caucasus to the Pacific. A particular focus of the series is the Silk Road in all of its ramifications: religion, art, music, medicine, science, trade, and so forth. Among the disciplines represented in this series are history, archeology, anthropology, ethnography, and linguistics. The series aims particularly to clarify the complex interrelationships among various peoples within Asia, and also with societies beyond Asia. A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher. Anderson_FoodEnvironmentChina_FM.indd 2 4/18/14 10:08 AM 22770 FO O D anD Environment IN earLY AND meDIEVAL CHINA E. N. ANDERSON university of pennsylvania press philadelphia Anderson_FoodEnvironmentChina_FM.indd 3 4/18/14 10:08 AM 22770 Copyright © 2014 University of Pennsylvania Press All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher. Published by University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112 -

1421 Project an Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to The

1421 Project An Interactive Qualifying Project Report submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by ___________________ _______________________ Angela Burrows Millisent Fury Hopkins Date: May 31, 2007 _______________________________ Professor John Wilkes, Advisor This report represents the work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of completion of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. ABSTRACT 3 2. INDRODUCTION 3 3. OVERVIEW 6 3.1. Literature Review 6 3.2. Global Inequality Debate 8 3.3. Academy of the Pacific Rim Charter School 8 3.4. Freshman Seminar 9 4. METHODOLOGY 10 5. OBSERVATIONS 11 6. UPDATED GOALS 14 7. DISCUSSION OF RESULTS 15 8. WPI FRESHMAN SEMINAR 16 8.1. THOUGHTS ON THE FUTURE 16 9. CONCLUSION 17 10.PERSONAL REACTIONS 18 APPENDICES A. PROPOSAL FOR THE 1421 PROJECT 19 B. INFORMATION ABOUT GLOBAL INQUALITY COURSE 25 C. REVIEWS OF SCHOLARLY WORKS 27 BIBLIOGRAPHY 35 Page 2 of 35 ABSTRACT The 1421 Project examines the educational implications of the book 1421: When China Discovered America, by Gavin Menzies. Meetings with area teachers were conducted to determine the best method of delivery of this controversial material into the school system. INTRODUCTION The 1421 IQP project was created with the intention to explore the implications for the Massachusetts high school social studies curriculum, if Gavin Menzies‘ claims are proved right in 10 years. The 1421 project team wanted to hold book club type meetings with teachers and curriculum specialists from the area in order to gather their thoughts on what might be the social implications of this information being included in a high school curriculum. -

Download PDF # Chinese Eunuchs

JKECEPQYTPVZ > Doc > Chinese eunuchs Chinese eunuchs Filesize: 8.52 MB Reviews This pdf is fantastic. It really is basic but shocks inside the 50 % in the pdf. I realized this pdf from my i and dad encouraged this pdf to discover. (Hunter Witting) DISCLAIMER | DMCA 0TM1PVGOCAYH ^ Book « Chinese eunuchs CHINESE EUNUCHS Reference Series Books LLC Apr 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 256x192x8 mm. This item is printed on demand - Print on Demand Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 42. Chapters: Han Dynasty eunuchs, Ming Dynasty eunuchs, Tang Dynasty eunuchs, Zheng He, Sima Qian, Cai Lun, Gao Lishi, Tian Lingzi, Qiu Shiliang, Yang Fugong, Li Fuguo, Tutu Chengcui, Yu Chao'en, Wang Shoucheng, Yishiha, Yang Fuguang, Cheng Yuanzhen, Tong Guan, Zhao Gao, Hong Bao, Zong Ai, Zhu Jingmei, Gang Bing, Liu Jin, Sun Cheng, Huang Hao, Zheng Zhong, Nguyen An, Zhou Man, Wei Zhongxian, Wang Jinghong, Li Lianying, Sun Yaoting, Wang Zhen, Zuo Feng, Eight Tigers. Excerpt: Zheng He (1371-1435, ¿¿ / ¿¿; pinyin: Zhèng Hé), also known as Ma Sanbao (¿¿¿ / ¿¿¿) and Hajji Mahmud Shamsuddin (Persian: ¿¿¿¿ ¿¿¿¿¿ ¿¿¿) was a Muslim Hui-Chinese mariner, explorer, diplomat and fleet admiral, who commanded voyages to Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and East Africa, collectively referred to as the Voyages of Zheng He or Voyages of Cheng Ho from 1405 to 1433. The route of the 7th voyage of Zheng He's fleet. Solid line: main fleet; dashed line: a possible route of Hong Bao's squadron; dotted line: a trip of seven Chinese sailors, including Ma Huan, from Calicut to Mecca on a native ship. Cities visited by Zheng He's fleet or its squadron on the 7th or any of the previous voyages are shown in red.Zheng, born as Ma He (¿¿ / ¿¿), was the second son of a Muslim family which also had four daughters, from Kunyang, present day Jinning, just south of Kunming near the southwest corner of Lake Dian in Yunnan. -

Chinese Fleets Set Sail

Reissue in Lisbon, Portugal on 10th anniversary, very limited edition. Postscript for events to 1431 in blue italics on right hand side of pages. SUPPLEMENT ISSUED IN LISBON, CHINESE FLEETS SET SAIL 8TH MARCH 1421 T I M E S TANGGREAT ARMADA GU FROM BEIJING SETS SAIL INTO THE UNKNOWN ON A VOYAGE OF 1000 DAYS INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Today, at 4.00 hrs local time The Mongols had ruled China DEPARTURE IN 1421 1 the largest fleet that the world since its conquest in 1279 by AND ALSO EARLIER THAN 1421 HISTORY has ever seen set sail from Kublai Khan, the grandson of AND VOYAGES Tanggu across the Yellow Sea. Genghis Khan. In 1352 the THE EMPEROR, THE 2 There are about 800 junks in peasants revolted plagued by ADMIRAL AND THE CANAL all. The merchant junks are 90 famine and disease. Zhu Yu- RISE AND FALL feet long by 30 feet wide. The anzhang, the son of a hired PORTUGAL (&SPAIN) 3 treasure ships are 480 feet labourer, became the leader. INHERIT THE CROWN THANKS TO long by 180 feet wide. There In 1356, his forces captured NICCOLÒ DA CONTI are over 100 of these which Nanjing and cut off corn sup- HONG BAO AND THE 3 have 16 internal watertight fast warships to protect the plies to Ta-tu (Beijing). In 1368 ANTARCTIC PENIN- SULA ZHOU MAN’S compartments, any 2 can be fleet. About 30,000 men made they entered Ta-tu and the CIRCUMNAVIGATION flooded without the ship sink- up the fleet —a trading country Mongol emperor fled. -

The Third-Phase of the Yungang Cave Complex—Its Architectural Structure, Subject Matter, Composition and Style

The Third-phase of the Yungang Cave Complex—Its Architectural Structure, Subject Matter, Composition and Style Volume One by Lidu Yi A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright 2010 by Lidu Yi The Third-phase of the Yungang Cave Complex—Its Architectural Structure, Subject Matter, Composition and Style Lidu Yi, Ph.D. 2010 Graduate Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto Abstract The Yungang Cave Complex in Shanxi province is one of the largest Buddhist sculpture repositories produced during the Northern and Southern Dynasties. This thesis argues that the iconographic evolution of the Yungang caves underwent three developing phases which can be summarized as the five Tan Yao Caves phase, the transitional period, and the sinicized third-phase under the reigns of five Northern Wei (386-534) emperors Wencheng (452-465), Xianwen (466-471), Xiaowen (471-499), Xuanwu (500-515) and Xiaoming (516-528). This dissertation studies the Yungang third-phase caves, namely those caves executed after the capital was moved from Pingcheng to Luoyang in the year 494. It focuses primarily on what we call the western-end caves, which are composed of all the caves from cave 21 to cave 45, and as cave 5-10 and cave 5-11 are typical representations of the third-phase and even today are well preserved, they are also included in this study. ii Using typology method, as well as primary literary sources, this study places the western-end caves in their historical, social and religious context while focusing on four perspectives: architectural lay-out, iconographic composition, subject matter and style of representation. -

Zheng He and His Envoys' Visits to Cairo in 1414 And

Zheng He and his Envoys’ Visits to Cairo in 1414 and 1433 Wang Tai Peng* Introduction Over a century, generation after generation of both western and Chinese historians has been trying in vain to solve this historical puzzle of who the 1433 Chinese ambassador to the papal court of Florence was. Yet it isn’t all that clueless as it seemed. Indeed there are clues in some Chinese contemporary source which might indicate the answer. In the seventh voyage of Admiral Zheng He, his deputy Hong Bao was instructed to lead his vast fleet to call at the kingdom of Calicut on November 18, 1432. Hong Bao arrived at the time when the kingdom was about to send its own fleet with an envoy to visit Tianfang or Mecca. The Chinese deputy admiral quickly took the opportunity to let seven of his interpreter officials in a trade delegation bearing silks and porcelains, to accompany the Calicut fleet to Mecca. A year later, the Chinese envoys were all reunited in the Jeddah port of the Mecca Kingdom before they returned to Calicut. They brought with them rare diamonds, exotic animals like lions, ostriches and giraffes which they had traded in the various Mediterranean countries. This very special trade delegation to Mecca returned to Calicut one year later. By then, it was already close to the end of 1433 and Zheng He’s ships had all but left Calicut in a rush home to China for more than half a year after his death was announced. This 1433 trade mission was extraordinarily special.