Research.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alumni Revue! This Issue Was Created Since It Was Decided to Publish a New Edition Every Other Year Beginning with SP 2017

AAlluummnnii RReevvuuee Ph.D. Program in Theatre The Graduate Center City University of New York Volume XIII (Updated) SP 2016 Welcome to the updated version of the thirteenth edition of our Alumni Revue! This issue was created since it was decided to publish a new edition every other year beginning with SP 2017. It once again expands our numbers and updates existing entries. Thanks to all of you who returned the forms that provided us with this information; please continue to urge your fellow alums to do the same so that the following editions will be even larger and more complete. For copies of the form, Alumni Information Questionnaire, please contact the editor of this revue, Lynette Gibson, Assistant Program Officer/Academic Program Coordinator, Ph.D. Program in Theatre, The Graduate Center, City University of New York, 365 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10016-4309. You may also email her at [email protected]. Thank you again for staying in touch with us. We’re always delighted to hear from you! Jean Graham-Jones Executive Officer Hello Everyone: his is the updated version of the thirteenth edition of Alumni Revue. As always, I would like to thank our alumni for taking the time to send me T their updated information. I am, as always, very grateful to the Administrative Assistants, who are responsible for ensuring the entries are correctly edited. The Cover Page was done once again by James Armstrong, maybe he should be named honorary “cover-in-chief”. The photograph shows the exterior of Shakespeare’s Globe in London, England and was taken in August 2012. -

The Showgirl Goes On

Star_Jan02_p1-20_Layout 1 1/2/2013 3:31 PM Page 1 ONLINE GET SELECT CONTENT ON THE GO, WWW.MONTROSE-STAR.COM IS MOBILE ENABLED! The WWW.MONTROSE-STAR.COM YOUR GUIDE TO GLBT ENTERTAINMENT, RECREATION & CULTURE IN CENTRAL AND COASTAL TEXAS WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 2, 2013 H VOL. III, ISSUE 20 FEATURE n19 One Good Love CALENDAR n6 Next2Weeks! DINING GUIDE n14 Roots Juice Drink Your Veggies! COMMUNITY n6 HAPPY NEW YEAR! The Showgirl INDEX Editorial........................4 Non-Profits Calendar .....16 Goes On Cartoons ....................33 Crossword ..................33 p10 Lifestyles ....................31 Star_Jan02_p1-20_Layout 1 1/2/2013 2:58 PM Page 2 Page 2 Montrose Star H Wednesday, January 2, 2013 www.Montrose-Star.com H also find us onn F Facebook.com/Star.Montrose Star_Jan02_p1-20_Layout 1 1/2/2013 2:58 PM Page 3 Montrose Star H Wednesday, January 2, 2013 Page 3 www.Montrose-Star.com H also find us onn F Facebook.com/Star.Montrose Star_Jan02_p1-20_Layout 1 1/2/2013 2:58 PM Page 4 Page 4 Montrose Star H Wednesday, January 2, 2013 Op-ED CONTACT US: 713-942-0084 EMAIL: [email protected] publisher Executive Editor Health & Fitness Music Laura M. Villagrán Kenton Alan DJ Chris Allen Sales Director Davey Wavey DJ JD Arnold Angela K. Snell Dr. Randy Mitchmore DJ Mark DeLange Creep of the Week: production News & Features DJ Wild & DJ Jeff Rafael Espinosa Johnny Trlica Scene Writers Circulation & Distribution Jim Ayers Arts Reviews Miriam Orihuela Pope Benedic XVI Daddy Bob Bill O’Rourke & Loyal K Elizabeth Membrillo Stephen Hill Lifestyles Rey Lopez Gayl Newton By d’anne WitkoWski lent to a suicide bomber. -

13-030113.Compressed.Pdf

King & Queen of the Rodeo BrlanBlck lJcIuolFlnt Schedule Of Events: Satu«iay Mlch 16,2013 !OOrsdri MatchlU13 8:30am· Mardattty NewContestant Meeq 2:00pm. fIllse Stdli(bec~~nbegi"6,Pasatna Fai~lOunds 9:ooam·H. Noolish (approUmatelyl· Grand Entry BAYOU BEAU 8:00pm. lone ~at lit ~v~,8's Aftemooo· Rodeoc.ontiwes ~gaCJ....•••9:00pm. ~amondsand Peansrnee~ DenimaM Spursatlre e,qs S:30pm •Happy Hour at TwoCities Bar and Grin CClfMNntt~ Health Services. Frilai MardiII, m13 7:00 pm· 0kIah00la Tea Party, EJ's "'_I ..u,•••" ••• 8:l0 am· Rodeo Sdilol Regi~lation SundaYMarch 17,lOll sabayc)ubeeu.com 9:00am· Rodeo Scoool and Safety Oass,PasaO!IIa Fai~roonds 9:30am·H. NooIish (approUmatelyl· Grand Entry 9:00am· HI.\'le1141(re~·in begms,PasadenaF~rgrcunds Aftemooo· Rodeoamtillles 6:00pmtil9:OO pm. ContestdntandVolJnteerRegistlilt~n, HllItHotel 7:00 pm· DiMer at the BRB Ii>. lO:OOpm·ffingIirue, HeI-n-Heek vsHell-n·Hoovesaltlf e,qs 8:00pm· Rodeo Awards at the BRB MONTROSEST.t ril ~ YELLOW V\:::IulOJHgt 10 nJU Hcu5"'Ol',GlBT Co' NO ".- ~ $1 cups -..~'tll the kegs run dry ~ MARCH 15&16 Sunday 3/10/13 @ 5:00 YOU JUST MIGHT GET 330 San Pedro, San Antonio, TX ~ ~b' AN~ "1 ufJ!lfJu Motivation By Jennifer Webb Perception My next series of articles deals with perception, us) we miss what's in front of our face. And we're because it can get in our way more than most of not alone. Everyone out there is doing the same us realize. And this week, let's look at how we can thing we are. -

1 Production Information in Just Go with It, a Plastic Surgeon

Production Information In Just Go With It, a plastic surgeon, romancing a much younger schoolteacher, enlists his loyal assistant to pretend to be his soon to be ex-wife, in order to cover up a careless lie. When more lies backfire, the assistant's kids become involved, and everyone heads off for a weekend in Hawaii that will change all their lives. Columbia Pictures presents a Happy Madison production, Just Go With It. Starring Adam Sandler and Jennifer Aniston. Directed by Dennis Dugan. Produced by Adam Sandler, Jack Giarraputo, and Heather Parry. Screenplay by Allan Loeb and Timothy Dowling. Based on ―Cactus Flower,‖ Screenplay by I.A.L. Diamond, Stage Play by Abe Burrows, Based upon a French Play by Barillet and Gredy. Executive Producers are Barry Bernardi, Allen Covert, Tim Herlihy, and Steve Koren. Director of Photography is Theo Van de Sande, ASC. Production Designer is Perry Andelin Blake. Editor is Tom Costain. Costume Designer is Ellen Lutter. Music by Rupert Gregson-Williams. Music Supervision by Michael Dilbeck, Brooks Arthur, and Kevin Grady. Just Go With It has been rated PG-13 by the Motion Picture Association of America for Frequent Crude and Sexual Content, Partial Nudity, Brief Drug References and Language. The film will be released in theaters nationwide on February 11, 2011. 1 ABOUT THE FILM At the center of Just Go With It is an everyday guy who has let a careless lie get away from him. ―At the beginning of the movie, my character, Danny, was going to get married, but he gets his heart broken,‖ says Adam Sandler. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Ukulele Club of Santa Cruz Songbook Part 2

Introduction D7 G D7 G 67 C G Honolulu Baby, where'd you get those eyes D7 G G7 And that dark complexion, I idolize C G Honolulu Baby, where'd you get that style D7 G G7 HHoonnoolluulluu BBaabbyy Those pretty red lips, that sunny smile Music and lyrics by T. Marvin Hatley C G October 1933 for "Sons of the Desert" Neath palm trees swaying, at Waikiki starring Laurel and Hardy D7 G G7 Ukulele Club of Santa Cruz February 2004 Honolulu Baby, you're the one for me D7 G C G Honolulu Baby, when you start to sway D7 G G7 All the men go crazy, they seem to say C G Honolulu Baby, where'd you get those eyes D7 G G7 And that dark complexion, I idolize C G 7 C G Honolulu Baby, where'd you get that style D7 G G7 Those pretty red lips, that sunny smile C G Neath palm trees swaying, at Waikiki D7 G G7 Honolulu Baby, you're the one for me C G Honolulu Baby, at Waikiki D7 G G7 Honolulu Baby, you're the one for me D7 G G7 Honolulu Baby, you're the one for me "...the real music's in your mind. All the instruments are just mechanics." --- Marvin Hatley, composer of "Honolulu Baby" End with D7 G D7 G No mention of Laurel and Hardy music is complete without a nod to Hatley's immortal "Honolulu Baby" from the Boys' 1933 feature, SONS OF THE DESERT. Used in the big convention scene where Stan and Ollie share their subterfuge with fellow Son Charley Chase, "Honolulu Baby" comes off as both a typical "Hollywood Production Number" and a gentle satire of the same. -

F1 30Bflrujitg Imt$ Rtemirtrri

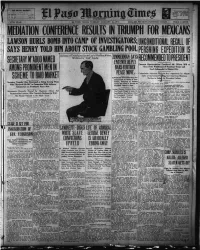

THE METAL MARKET - "ihh may rrvme- mm a wwiK of m(lfnt rtemirtrri arlvrsnistna: 1 Ittern uml be Slew Tat xlrcr--. n. Nee Vis lea .. Bflrujitg imt$ 37TH YEAR f 30EL PASO, TEXAS. TUESDAY. JANUARY 16, 1917. ENGLISH SECTION--FOURTEE- PAGES. PRICE 5 CENTS MEDIATION CONFERENCE RESULTS IN TRIUMPH FOR MEXICANS LAWSON HURLS BOMB INTO CAMP OF INVESTIGATORS; UNCONDITIONAL RECALL OF - SAYS HENRY TOLD HIM ABOUT STOCK GAMBLING POOL PERSHING EXPEDITION IS Treasury SonrkrLaw President Wilson, Secretary of and of ZIMMERMAN SAYS Mentioned in Inquiry. REliUMMENDED TIJ PRESIDENT SECRETARY NAMED "Leak" M100 ENTENTE REPLY a aBstta9 Carranza Representatives) Convinced Mr. Wilson Will at AMONG PROMINENT MEN IN BARS FURTHER Once Order Withdrawal of American Troop and Send Ambassador to Mexico City. v Ikn. PEACEMOVE. ttttttW Commission Adjourns Without Any Agreement for Adjust BkL SCHEME TO RAID MARKET ment of Questions PeraMhfj, but American Member In Particular It Preclude Any An Decline to Admit Its Complete Failure. nouncement by Berlin of Con ÉtWW Designed to Answer Secretary Tumulty Also Mentioned as Being Among Those sBBBbV atsm diliont. Associated prcas. Terms Set Forth in Answer to New York, Jan. It The Mexican Ameri- Who "Received His Bit" in Connection With Advance can Joint commission which railed to er- President Wilson's Note 01 TRKTAnO f'ONt EVTION TO or Is- Information on President's Peace Note. red an adjustment the queeunn at imVCLl'DE WORK THIS MONTH. ' sue between Mexico and Uie Cnltcd State By Associated press Is Foreign Minister Declares Door after e series tr conference that began Otieretaro. Jan. ir. -

Judy's Dietglue

Judy’s DietGlue The “How to Stick to Any Sensible Weight-Control Plan” Guidebook Judy Payne Judy’s DietGlue: Th e “How to Stick to Any Sensible Weight-Control Plan” Guidebook By Judy Payne Copyright © 2014 Judy Payne Published by Long-Term Success Publishing All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or por- tions thereof in any form (except where permitted by law) without the prior written permission of Long-Term Success Publishing. For more information, please contact: [email protected]. (Anyone who decides to snitch Judy’s hard work without paying for it should be ashamed of themselves!) Editor: Linda M. Meyer Proofreader: Jennifer Weaver-Neist Graphic artist: Lisa Meyer Book Interior Designer: Susan Veach Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ISBN-13: 978-1-49734-036-7 ISBN-10: 149734-036-5 LCCN You can contact Judy through any of the following ways: E-mail: [email protected] Website: judypayne.com Blog: judypayne.com/blog Facebook: facebook.com/skinnyschool Twitter: twitter.com/skinnyschool Pinterest: pinterest.com/skinnyschool If you enjoy this book, please consider leaving your review at http://www.amazon.com/ dp/1497340365 To my beloved mom, for trying to convince me that cottage cheese was not disgusting Contents Acknowledgements . 1 Disclaimer . 3 A Howdy from Judy . 5 Judy’s 1-2-3-4-Step Approach to Permanent Weight Control . 7 Part I—Benefi ts You Can’t Find Anywhere Else But in Judy’s DietGlue . 9 1 Descriptions of the Unique Benefi ts of Th is “Not a Diet Book” Book . -

HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007

1 HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007 Submitted by Gareth Andrew James to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, January 2011. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ........................................ 2 Abstract The thesis offers a revised institutional history of US cable network Home Box Office that expands on its under-examined identity as a monthly subscriber service from 1972 to 1994. This is used to better explain extensive discussions of HBO‟s rebranding from 1995 to 2007 around high-quality original content and experimentation with new media platforms. The first half of the thesis particularly expands on HBO‟s origins and early identity as part of publisher Time Inc. from 1972 to 1988, before examining how this affected the network‟s programming strategies as part of global conglomerate Time Warner from 1989 to 1994. Within this, evidence of ongoing processes for aggregating subscribers, or packaging multiple entertainment attractions around stable production cycles, are identified as defining HBO‟s promotion of general monthly value over rivals. Arguing that these specific exhibition and production strategies are glossed over in existing HBO scholarship as a result of an over-valuing of post-1995 examples of „quality‟ television, their ongoing importance to the network‟s contemporary management of its brand across media platforms is mapped over distinctions from rivals to 2007. -

00:00:00 Music Transition Gentle, Trilling Music with a Steady Drumbeat Plays Under the Dialogue

00:00:00 Music Transition Gentle, trilling music with a steady drumbeat plays under the dialogue. 00:00:01 Promo Promo Speaker: Bullseye with Jesse Thorn is a production of MaximumFun.org and is distributed by NPR. [Music fades out.] 00:00:12 Music Transition “Huddle Formation” from the album Thunder, Lightning, Strike by The Go! Team. 00:00:19 Jesse Host It’s Bullseye. I’m Jesse Thorn. Terrace Martin—a musician and Thorn producer—was born in Los Angeles’s Crenshaw District. He first started in music as a saxophonist who played in jazz bands, went to an arts high school, and even went to band camp. He wasn’t much older than 18 when he figured out that life wasn’t for him. At the same, the kids growing up around him were freestyling and making mixtapes and beats. And who wouldn’t be excited about that? With those two parallel backgrounds, Terrace kicked off a career that would make him a trailblazing polymath in popular music. As a producer, he’s worked with Snoop Dogg, Charlie Wilson, YG, Kendrick Lamar. As a solo artist, he’s released about half a dozen albums. Terrace channels classic artists like Sly Stone, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, and Herbie Hancock, while also landing some pretty great features—heavy hitters like Kamasi Washington, Thundercat, Wiz Khalifa, and the aforementioned K Dot. Terrace isn’t the kind of guy to be slowed down by anything, including a pandemic. [Music fades in.] In 2020, he released seven EPs, including Village Days, a record that features a jazz tribute to the late Nipsey Hussle. -

2010 Joint Conference of the National Popular Culture and American Culture Associations

2010 Joint Conference of the National Popular Culture and American Culture Associations March 31 – April 3, 2010 Rennaisance Grand Hotel St. Louis Delores F. Rauscher, Editor & PCA/ACA Conference Coordinator Jennifer DeFore, Editor & Assistant Coordinator Michigan State University Elna Lim, Wiley-Blackwell Editor Additional information about the PCA/ACA available at www.pcaaca.org 2 Table of Contents The 2009 National Conference Popular Culture Association & American Culture Association Area Chairs ___________________ 5 PCA/ACA Board Members _______________________________ 13 Officers _______________________________________________ 13 Executive Officers ______________________________________ 13 Past & Future Conferences _______________________________ 14 Conference Papers for Sale; Benefits Endowment _____________ 15 Exhibit Hours __________________________________________ 15 Business & Board Meetings _______________________________ 16 Film Screenings ________________________________________ 18 Dinners, Get-Togethers, Receptions, & Tours ________________ 23 Roundtables ___________________________________________ 25 Special Sessions ______________________________________________ 29 Schedule Overview ______________________________________ 33 Saturday ____________________________________________________ 54 Daily Schedule _________________________________________ 77 Wednesday, 12:30 P.M. – 2:00 P.M. ____________________________ 77 Wednesday, 2:30 P.M. – 4:00 P.M. ____________________________ 83 Wednesday, 4:30 P.M. – 6:00 P.M. ____________________________ -

The Construction of Listening in Electroacoustic Music Discourse

Learning to Listen: The Construction of Listening in Electroacoustic Music Discourse Michelle Melanie Stead School of Humanities and Communication Arts Western Sydney University. September, 2016 A thesis submitted as fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Western Sydney University. To the memories of my father, Kenny and my paternal grandmother, Bertha. <3 Acknowledgements Firstly, to Western Sydney University for giving me this opportunity and for its understanding in giving me the extra time I needed to complete. To my research supervisors, Associate Professor Sally Macarthur and Dr Ian Stevenson: This thesis would not have been possible without your mentorship, support, generosity, encouragement, guidance, compassion, inspiration, advice, empathy etc. etc. … The list really is endless. You have both extended your help to me in different ways and you have both played an essential role in my development as an academic, teacher and just ... as a human being. You have both helped me to produce the kind of dissertation of which I am extremely proud, and that I feel is entirely worth the journey that it has taken. A simple thank you will never seem enough. To all of the people who participated in my research by responding to the surveys and those who agreed to be interviewed, I am indebted to your knowledge and to your expertise. I have learnt that it takes a village to write a PhD and, along with the aforementioned, ‗my people‘ have played a crucial role in the development of this research that is as much a personal endeavour as it is a professional one.