Biography Is an Attempt to Accurately Portray R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oneg 6 – Toldos 2018

1 Oneg! A collection of fascinating material on the weekly parsha! Rabbi Elchanan Shoff Parshas TOLDOS Avraham begat Yitzchak (Gen. 25:19). The Or Hachaim and R. Shlomo Kluger (Chochmas Hatorah, Toldos p. 3) explain that it was in Avraham’s merit that G-d accepted Yitzchak’s prayers and granted him offspring. Rashi (to Gen. 15:15, 25:30) explains that G-d had Avraham die five years earlier than he otherwise should have in order that Avraham would not see Yitzchak’s son Esau stray from the proper path. I saw in the name of R. Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld (Chochmas Chaim to Toldos) that if Yitzchak had not campaigned vigorously in prayer to father a child, G-d would have granted him children anyways after five years. So in which merit did Yitzchak father his children, in Avraham’s merit or in the merit of his own prayers? Both are true: It was only in Avraham’s merit that Yitzchak deserved to father Yaakov and Esau, but the fact that the twins were born earlier rather than later came in merit of Yitzchak’s prayers. R. Sonnenfeld adds that the Torah’s expression equals in Gematria the (748 = ויעתר לו י-ה-ו-ה) that denotes G-d heeding Yitzchak’s prayers .The above sefer records that when a grandson of R .)748 = חמש שנים) phrase five years Sonnenfeld shared this Gematria with R. Aharon Kotler, he was so taken aback that he exclaimed, “I am certain that this Gematria was revealed through Ruach HaKodesh!” Yitzchak was forty years old when he took Rivkah—the daughter of Besuel the Aramite from Padan Aram, the sister of Laban the Aramite—as a wife (Gen. -

The American Rabbinic Career of Rabbi Gavriel Zev Margolis By

The American Rabbinic Career of Rabbi Gavriel Zev Margolis i: by Joshua Hoffman In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Modern Jewish History Sponsored by Dr. Jeffrey Gurock Bernard Revel Graduate School Yeshiva University July, 1992 [ rI'. I Table of Contents Introduction. .. .. • .. • . • .. • . .. .• 1 - 2 Chapter One: Rabbi Margolis' Background in Russia, 1847-1907•••••••.••.•••••••••••••.•••.•••.•••..•.• 3 - 18 Chapter Two: Rabbi Margolis' Years in Boston, 1907-1911........................................ 19 - 31 Chapter Three: Rabbi Margolis' Years in New York, 1911-1935••••••••••••••••••••••••••••.•••••••..••. 32 - 119 A. Challenging the Kehillah.. ... ..... ....... 32 - 48 B. Confronting the Shochtim and the Agudat Harabbonim.• .. •.. •.. •..•....••... ... .. 49 - 88 c. The Knesset Harabbonim... .... .... .... ... •. 89 - 121 Conclusions. ..................................... 122 - 125 Appendix . ........................................ 126 - 132 Notes....... .. .... .... ....... ... ... .... ..... .... 133 - 155 Bibliography .....•... •.•.... ..... .•.. .... ...... 156 - 159 l Introduction Rabbi Gavriel zev Margolis (1847-1935) is one of the more neglected figures in the study of American Orthodoxy in the early 1900' s. Although his name appears occasionally in studies of the period, he is generally mentioned only briefly, and assigned a minor role in events of the time. A proper understanding of this period, however, requires an extensive study of his American career, because his opposition -

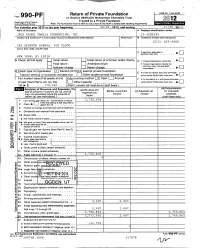

Return of Private Foundation

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545 -0052 Fonn 990 -PFI or Section 4947( a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation 2012 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Sennce Note The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements For calendar year 2012 or tax year beginning 12/01 , 2012 , and endii 11/30. 2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number JACK ADJMT FAMILY FOUNDATION. INC. 13-3202295 Number and street ( or P 0 box number If mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number ( see instructions) (212) 629-9600 463 SEVENTH AVENUE, 4TH FLOOR City or town, state , and ZIP code C If exemption application is , q pending , check here . NEW YORK, NY 10018 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1 Foreign organ izations . check here El Final return Amended return 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach Address change Name chang e computation . • • • • • • . H Check type of organization X Section 501 ( cJ 3 exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947 ( a )( 1 nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation under section 507(bxlXA ), check here . Ill. El I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accountin g method X Cash L_J Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination of year (from Part Il, col. (c), line 0 Other ( specify) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ under section 507(b )( 1)(B), check here 16) 10- $ 17 0 , 2 4 0 . -

TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 a Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 A Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M. Joel WITH SHAVUOT TRIBUTES FROM Rabbi Dr. Kenneth Brander • Rabbi Dr. Hillel Davis • Rabbi Dr. Avery Joel • Dr. Penny Joel Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph • Rabbi Menachem Penner • Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter • Rabbi Ezra Schwartz Special Symposium: Perspectives on Conversion Rabbi Eli Belizon • Joshua Blau • Mrs. Leah Nagarpowers • Rabbi Yona Reiss Rabbi Zvi Romm • Mrs. Shoshana Schechter • Rabbi Michoel Zylberman 1 Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Shavuot 5777 We thank the following synagogues which have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Beth David Synagogue Green Road Synagogue Young Israel of West Hartford, CT Beachwood, OH Century City Los Angeles, CA Beth Jacob Congregation The Jewish Center Beverly Hills, CA New York, NY Young Israel of Bnai Israel – Ohev Zedek Young Israel Beth El of New Hyde Park New Hyde Park, NY Philadelphia, PA Borough Park Koenig Family Foundation Young Israel of Congregation Brooklyn, NY Ahavas Achim Toco Hills Atlanta, GA Highland Park, NJ Young Israel of Lawrence-Cedarhurst Young Israel of Congregation Cedarhurst, NY Shaarei Tefillah West Hartford West Hartford, CT Newton Centre, MA Richard M. Joel, President and Bravmann Family University Professor, Yeshiva University Rabbi Dr. Kenneth -

Religious Zionism: Tzvi Yehuda Kook on Redemption and the State Raina Weinstein Wednesday, Aug

Religious Zionism: Tzvi Yehuda Kook on Redemption and the State Raina Weinstein Wednesday, Aug. 18 at 11:00 AM EDT Course Description: In May 1967, Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook delivered a fiery address criticizing the modern state of Israel for what he viewed as its founding sin: accepting the Partition Plan and dividing the Land of Israel. “Where is our Hebron?” he cried out. “Where is our Shechem, our Jericho… Have we the right to give up even one grain of the Land of God?” Just three weeks later, the Six Day War broke out, and the Israeli army conquered the biblical heartlands that Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda had mourned—in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Sinai Peninsula, and Golan Heights. Hebron, Shechem, and Jericho were returned to Jewish sovereignty. In the aftermath of the war, Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda’s words seemed almost prophetic. His spiritual vision laid the foundation for a new generation of religious Zionism and the modern settler movement, and his ideology continues to have profound implications for contemporary Israeli politics. In this session, we will explore Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook’s 1967 speech, his teachings, and his critics— particularly Rabbi Yehuda Amital. Guiding Questions: 1. How does Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook interpret the quotation from Psalm 107: "They have seen the works of the Lord and His wonders in the deep"? Why do you think he begins this speech with this scripture? 2. In the section, "They Have Divided My Land," Rav Tzvi Yehuda Kook tells two stories about responses to partition. Based on these stories, what do you think is his attitude toward diplomacy and politics is? 1 of 13 tikvahonlineacademy.org/ 3. -

Lanrjp[;J 0 Tbe Yeshiva College Debating Rabbi Joseph B

.r,,:. ··r-:. · t ::- . i • . r .··Jc.in the SAC ·: ~ _:· ~.- ~; i :!. i ~ ;\ ~ ~= ~:·_ ··!(-· ; -~-- ·. 1~ f?: ~--:~ ~- :} -:_}!;:-: ~-~ r·:-~ :· .-~~r Red Cro$s . -:. -,:,• ...,. ·-:.,r.,. ,: .· . :. ) .. ··;: , .;£< _.: . ·· - l .~:-e :: :. B~od Dri~e , , . -~ • ' . ··_ r' :" ~ '. • (.;; ,: •• ~- .. Official Undergradua~e N~w~p~p~r of Yeshiva CQU~ge '..r VOLUME XXXVII NEW YORK CITY, MONDAY, · MARCH 16, 1953 · I / Debawrs Win ·:Ra,b·'-;~b-· ·1··: 1•t·· ·14l·k; · · &.·::~ :,dJ.~Jls~-i~,.-t;a_~;i -~ .·. Sol· o. ·ve·. ,. ·c··..· h .... .· .ft:UU-aF~ . ~a'.', Twenty-Three, Beat Harvard Overflow Crowd l~ LanrJp[;j 0 Tbe Yeshiva College Debating Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, Professor of Talmud and .Jewish Philosophy, and Dr. Samuel Belkin, Pres~ Soeiety launched- upon its annual ident of Yeshiva, were the principal speakers at the Smicha convocation exercises held SUnday, .'March tours throughout the East Coast, 8, in Nathan Lamport Auditorium. Eighty-three rabbis, ordained during 1950-53, participated in from Monday to Thursday, Feb the exercises. Of these, ten are serving as chaplains in the armed forces. Three other rabbis, who ruary 23-26. The record of the are at present in Israel, were honored in absentia. , ' Debatin~ Team for this season "Too many rabbis today have 'messiah-complexes'," Rabbi Soloveitchik declared. "They: attempt to stands at 23 victories and 7 de save the world with large scale projects and forget to worry about the individual Jew.•• · - · feats. "We are not revivalists, hoping to appeal to large masses in great demonstrations. We must concen The New England team com trate on individuals," he said. He urged the newly-ordained rabbis to . stress the importance of Jewish prising Gil Rosenthal '53 and learning, and use the medium of education as a means to influence members of their co11gregations. -

Rabbi Avraham Yizhak Hacohen Kook: Between Exile and Messianic Redemption*

Rabbi Avraham Yizhak HaCohen Kook: Between Exile and Messianic Redemption* Judith Winther Copenhagen Religious Zionism—Between Messsianism and A-Messianism Until the 19th century and, to a certain ex- tute a purely human form of redemption for a tent, somewhat into the 20th, most adherents redeemer sent by God, and therefore appeared of traditional, orthodox Judaism were reluc- to incite rebellion against God. tant about, or indifferent towards, the active, Maimonides' active, realistic Messianism realistic Messianism of Maimonides who averr- was, with subsequent Zionist doctrines, first ed that only the servitude of the Jews to foreign reintroduced by Judah Alkalai, Sephardic Rab- kings separates this world from the world to bi of Semlin, Bessarabia (1798-1878),3 and Zwi come.1 More broadly speaking, to Maimonides Hirsch Kalisher, Rabbi of Thorn, district of the Messianic age is the time when the Jewish Poznan (1795-1874).4 people will liberate itself from its oppressors Both men taught that the Messianic pro- to obtain national and political freedom and cess should be subdivided into a natural and independence. Maimonides thus rejects those a miraculous phase. Redemption is primari- Jewish approaches according to which the Mes- ly in human hands, and redemption through a sianic age will be a time of supernatural qual- miracle can only come at a later stage. They ities and apocalyptic events, an end to human held that the resettling and restoration of the history as we know it. land was athalta di-geullah, the beginning of Traditional, orthodox insistence on Mes- redemption. They also maintained that there sianism as a passive phenomenon is related to follows, from a religious point of view, an obli- the rabbinic teaching in which any attempt to gation for the Jews to return to Zion and re- leave the Diaspora and return to Zion in order build the country by modern methods. -

Alabama Arizona Arkansas California

ALABAMA ARKANSAS N. E. Miles Jewish Day School Hebrew Academy of Arkansas 4000 Montclair Road 11905 Fairview Road Birmingham, AL 35213 Little Rock, AR 72212 ARIZONA CALIFORNIA East Valley JCC Day School Abraham Joshua Heschel 908 N Alma School Road Day School Chandler, AZ 85224 17701 Devonshire Street Northridge, CA 91325 Pardes Jewish Day School 3916 East Paradise Lane Adat Ari El Day School Phoenix, AZ 85032 12020 Burbank Blvd. Valley Village, CA 91607 Phoenix Hebrew Academy 515 East Bethany Home Road Bais Chaya Mushka Phoenix, AZ 85012 9051 West Pico Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90035 Shalom Montessori at McCormick Ranch Bais Menachem Yeshiva 7300 N. Via Paseo del Sur Day School Scottsdale, AZ 85258 834 28th Avenue San Francisco, CA 94121 Shearim Torah High School for Girls Bais Yaakov School for Girls 6516 N. Seventh Street, #105 7353 Beverly Blvd. Phoenix, AZ 85014 Los Angeles, CA 90035 Torah Day School of Phoenix Beth Hillel Day School 1118 Glendale Avenue 12326 Riverside Drive Phoenix, AZ 85021 Valley Village, CA 91607 Tucson Hebrew Academy Bnos Devorah High School 3888 East River Road 461 North La Brea Avenue Tucson, AZ 85718 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Yeshiva High School of Arizona Bnos Esther 727 East Glendale Avenue 116 N. LaBrea Avenue Phoenix, AZ 85020 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Participating Schools in the 2013-2014 U.S. Census of Jewish Day Schools Brandeis Hillel Day School Harkham Hillel Hebrew Academy 655 Brotherhood Way 9120 West Olympic Blvd. San Francisco, CA 94132 Beverly Hills, CA 90212 Brawerman Elementary Schools Hebrew Academy of Wilshire Blvd. Temple 14401 Willow Lane 11661 W. -

The Jewish Observer

··~1 .··· ."SH El ROT LEUMI''-/ · .·_ . .. · / ..· .:..· 'fo "ABSORPTION" •. · . > . .· .. ·· . NATIONALSERVICE ~ ~. · OF SOVIET. · ••.· . ))%, .. .. .. · . FOR WOMEN . < ::_:··_---~ ...... · :~ ;,·:···~ i/:.)\\.·:: .· SECOND LOOKS: · · THE BATil.E · . >) .·: UNAUTHORIZED · ·· ·~·· "- .. OVER CONTROL AUTOPSIES · · · OF THE RABBlNATE . THE JEWISH OBSERVER in this issue ... DISPLACED GLORY, Nissan Wo/pin ............................................................ 3 "'rELL ME, RABBI BUTRASHVILLI .. ,"Dov Goldstein, trans lation by Mirian1 Margoshes 5 So~rn THOUGHTS FROM THE ROSHEI YESHIVA 8 THE RABBINATE AT BAY, David Meyers................................................ 10 VOLUNTARY SERVICE FOR WOMEN: COMPROMISE OF A NATION'S PURITY, Ezriel Toshavi ..... 19 SECOND LOOKS RESIGNATION REQUESTED ............................................................... 25 THE JEWISH OBSERVER is published monthly, except July and August, by the Agudath Israel of America, 5 Beekman Street, New York, New York 10038. Second class postage paid at New York, N. Y. Subscription: $5.00 per year; Two years, $8.50; Three years, $12.00; outside of the United States, $6.00 per year. Single copy, fifty cents. SPECIAL OFFER! Printed in the U.S.A. RABBI N ISSON W OLPJN THE JEWISH OBSERVER Editor 5 Beekman Street 7 New York, N. Y. 10038 Editorial Board D NEW SUBSCRIPTION: $5 - 1 year of J.O. DR. ERNEST L. BODENHEIMER Plus $3 • GaHery of Portraits of Gedolei Yisroel: FREE! Chairman RABBI NATHAN BULMAN D RENEWAL: $12 for 3 years of J.0. RABBI JOSEPH ELIAS Plus $3 - Gallery of Portraits of Gedo lei Yisroel: FREE! JOSEPH FRIEDENSON D GIFT: $5 - 1 year; $8.50, 2 yrs.; $12, 3 yrs. of ].0. RABBI YAACOV JACOBS Plus $3 ·Gallery of Portraits of Gedolei Yisroel: FREE! RABBI MOSHE SHERER Send '/Jf agazine to: Send Portraits to: THE JEWISH OBSERVER does not iVarne .... -

1 Beginning the Conversation

NOTES 1 Beginning the Conversation 1. Jacob Katz, Exclusiveness and Tolerance: Jewish-Gentile Relations in Medieval and Modern Times (New York: Schocken, 1969). 2. John Micklethwait, “In God’s Name: A Special Report on Religion and Public Life,” The Economist, London November 3–9, 2007. 3. Mark Lila, “Earthly Powers,” NYT, April 2, 2006. 4. When we mention the clash of civilizations, we think of either the Spengler battle, or a more benign interplay between cultures in individual lives. For the Spengler battle, see Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996). For a more benign interplay in individual lives, see Thomas L. Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999). 5. Micklethwait, “In God’s Name.” 6. Robert Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). “Interview with Robert Wuthnow” Religion and Ethics Newsweekly April 26, 2002. Episode no. 534 http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/week534/ rwuthnow.html 7. Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity, 291. 8. Eric Sharpe, “Dialogue,” in Mircea Eliade and Charles J. Adams, The Encyclopedia of Religion, first edition, volume 4 (New York: Macmillan, 1987), 345–8. 9. Archbishop Michael L. Fitzgerald and John Borelli, Interfaith Dialogue: A Catholic View (London: SPCK, 2006). 10. Lily Edelman, Face to Face: A Primer in Dialogue (Washington, DC: B’nai B’rith, Adult Jewish Education, 1967). 11. Ben Zion Bokser, Judaism and the Christian Predicament (New York: Knopf, 1967), 5, 11. 12. Ibid., 375. -

Motzoei Shabbos at the Agudath Israel Convention 2015

Motzoei Shabbos at the Agudath Israel Convention 2015 November 15, 2015 Following a beautiful, uplifting Shabbos, Motzoei Shabbos at the 93rd annual Agudath Israel of America convention combined inspiration and the tackling of difficult communal issues, under the banner of the convention’s theme of “Leadership.” Keynote Session At 8:30 pm, the main hotel ballroom was once again full, for the Motzoei Shabbos Keynote Session. In addition to the overflow crowd in the Convention Hotel itself, many additional thousands followed the session electronically.The dais featured leading gedolim of our generation, including two special guests from Eretz Yisroel, HaRav Dov Yaffe, Mashgiach in Yeshiva Knesses Chizkiyahu; and the Sadigura Rebbe. Convention Chairman Binyomin Berger spoke about Agudath Israel of America’s leadership on behalf of the needs of every individual in klal Yisroel, from cradle to grave. He praised the strong representation of young individuals at the convention, who are willing to roll up their sleeves on behalf of our community. “None of us are smarter than all us,” he exclaimed. The Novominsker Rebbe, Rosh Agudas Yisroel and member of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah of America, was in Eretz Yisroel for a family simcha. The Rebbe delivered a special video message to the convention, highlighting both the physical and spiritual dangers our community faces, and once again stressed the dangers of the burgeoning “Open Orthodoxy” movement. “These are the chevlai moshiach,” the Rebbe exclaimed. “We must think and breathe emunah; think and breathe ahavas Torah and yiras shamayim; and think and breathe tzedaka v’chessed.” Shabbos was the yartzeit of HaRav Aharon Kotler zt”l, legendary Rosh Yeshiva of Bais Medrash Govoha of Lakewood. -

Torah Weekly

בס״ד Torah Defining Work One generations as an everlasting conventional understanding covenant. Between Me and is that we spend six days of Weekly of the most important the children of Israel, it is the week working and practices in Judaism, the forever a sign that [in] six pursuing our physical needs, February 28- March 6, 2021 fourth of the Ten 16-22 Adar, 5781 days the L-rd created the and on the seventh day we Commandments, is to heaven and the earth, and on rest from the pursuit of the First Torah: refrain from work on the Ki Tisa: Exodus 30:11 - 34:35 the seventh day He ceased physical and dedicate a day Second Torah: seventh day, to sanctify it and rested. (Exodus 31:16- to our family, our soul and Parshat Parah: Numbers 19:1-22 and make it holy. Yet, the 17.) our spiritual life. Yet the exact definition of rest and PARSHAT KI TISA From the juxtaposition of Torah is signaling to us that forms of labor prohibited Shabbat and the we should think about labor We have Jewish on Shabbat are not explicitly commandment to build the in the context of the work Calendars. If you stated in the Torah. necessary to construct the would like one, Tabernacle, we derive that The Sages of sanctuary. please send us a the Tabernacle may not be the Talmud explain that the constructed on Shabbat. This Thus, the halachic definition letter and we will Torah alludes to there being send you one, or implies that any labor that of “labor” is derived from 39 categories of prohibited ask the was needed for the the labor used for the Calendars labor.