Uncle Sam's War of 1898 and the Origins of Globalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Popular Sovereignty, Slavery in the Territories, and the South, 1785-1860

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Popular sovereignty, slavery in the territories, and the South, 1785-1860 Robert Christopher Childers Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Childers, Robert Christopher, "Popular sovereignty, slavery in the territories, and the South, 1785-1860" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1135. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1135 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. POPULAR SOVEREIGNTY, SLAVERY IN THE TERRITORIES, AND THE SOUTH, 1785-1860 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Robert Christopher Childers B.S., B.S.E., Emporia State University, 2002 M.A., Emporia State University, 2004 May 2010 For my wife ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing history might seem a solitary task, but in truth it is a collaborative effort. Throughout my experience working on this project, I have engaged with fellow scholars whose help has made my work possible. Numerous archivists aided me in the search for sources. Working in the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill gave me access to the letters and writings of southern leaders and common people alike. -

The United States Versus Germany (1891-1910)

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects History Department 5-1995 Quest for Empire: The United States Versus Germany (1891-1910) Jennifer L. Cutsforth '95 Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/history_honproj Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Cutsforth '95, Jennifer L., "Quest for Empire: The United States Versus Germany (1891-1910)" (1995). Honors Projects. 28. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/history_honproj/28 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. ~lAY 12 1991 Quest For Empi re: The Uni ted states Versus Germany (1891 - 1910) Jenn1fer L. Cutsforth Senlor Research Honors Project -- Hlstory May 1995 • Quest for Emp1re: The Un1ted states versus Germany Part I: 1891 - 1900 German battleships threaten American victory at Man'ila! United States refuses to acknowledge German rights in Samoa! Germany menaces the Western Hemispherel United States reneges on agreement to support German stand at Morocco! The age of imperi aIi sm prompted head 1ines I" ke these in both American and German newspapers at the turn of the century, Although little contact took place previously between the two countries, the diplomacy which did exist had been friendly in nature. -

30Th ANNIVERSARY 30Th ANNIVERSARY

July 2019 No.113 COMICS’ BRONZE AGE AND BEYOND! $8.95 ™ Movie 30th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 7 with special guests MICHAEL USLAN • 7 7 3 SAM HAMM • BILLY DEE WILLIAMS 0 0 8 5 6 1989: DC Comics’ Year of the Bat • DENNY O’NEIL & JERRY ORDWAY’s Batman Adaptation • 2 8 MINDY NEWELL’s Catwoman • GRANT MORRISON & DAVE McKEAN’s Arkham Asylum • 1 Batman TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. JOEY CAVALIERI & JOE STATON’S Huntress • MAX ALLAN COLLINS’ Batman Newspaper Strip Volume 1, Number 113 July 2019 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! Michael Eury TM PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST José Luis García-López COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek IN MEMORIAM: Norm Breyfogle . 2 SPECIAL THANKS BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . 3 Karen Berger Arthur Nowrot Keith Birdsong Dennis O’Neil OFF MY CHEST: Guest column by Michael Uslan . 4 Brian Bolland Jerry Ordway It’s the 40th anniversary of the Batman movie that’s turning 30?? Dr. Uslan explains Marc Buxton Jon Pinto Greg Carpenter Janina Scarlet INTERVIEW: Michael Uslan, The Boy Who Loved Batman . 6 Dewey Cassell Jim Starlin A look back at Batman’s path to a multiplex near you Michał Chudolinski Joe Staton Max Allan Collins Joe Stuber INTERVIEW: Sam Hamm, The Man Who Made Bruce Wayne Sane . 11 DC Comics John Trumbull A candid conversation with the Batman screenwriter-turned-comic scribe Kevin Dooley Michael Uslan Mike Gold Warner Bros. INTERVIEW: Billy Dee Williams, The Man Who Would be Two-Face . -

Myth and Carnival in Robert Coover's the Public Burning

ROBERTO MARIA DAINOTTO Myth and Carnival in Robert Coover's The Public Burning Certain situations in Coover's fictions seem to conspire with a sense of impending disaster, which we have visited upon us from day to day. We have had, in that sense, an unending sequence of apocalypses, long before Christianity began and up to the present... in a lot of contemporary fiction there's a sense of foreboding disaster which is part of the times, just like self reflexive fictions. (Coover 1983, 78) As allegory, the trope of the apocalypse—a postmodern version of the Aristotelian tragic catastrophe—stands at the center of Coover's choice of content, his method of treating his materials, and his view of writing. In his fictions, one observes desperate people caught in religious nightmares leading to terrible catastrophes, a middle-aged man whose life is sacrificed at the altar of an imaginary baseball game, beautiful women repeatedly killed in the Gothic intrigues of Gerald's Party, and other hints and omens of death and annihilation. And what about the Rosenbergs, whom the powers that be "determined to burn... in New York City's Times Square on the night of their fourteenth wedding anniversary, Thursday, June 18, 1953"(PB 3)?1 In The Public Burning, apocalypse becomes holocaust—quite literally, the Greek holokauston, a "sacrifice consumed by fire." What proves interesting from a narrative point of view is that Coover makes disaster, apocalypse and holocaust part of the materials of the fictions" of the times"—which he calls" self-reflexive fictions." But what is the relation between genocide, human annihilation, and self-reflexive fictions? How do fictions" of the times" reflect holocaust? Larry McCaffery suggests: 6 Dainotto in most of Coover's fiction there exists a tension between the process of man creating his fictions and his desire to assert that his systems have an independent existence of their own. -

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Ralph

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Ralph H. Records Collection Records, Ralph Hayden. Papers, 1871–1968. 2 feet. Professor. Magazine and journal articles (1946–1968) regarding historiography, along with a typewritten manuscript (1871–1899) by L. S. Records, entitled “The Recollections of a Cowboy of the Seventies and Eighties,” regarding the lives of cowboys and ranchers in frontier-era Kansas and in the Cherokee Strip of Oklahoma Territory, including a detailed account of Records’s participation in the land run of 1893. ___________________ Box 1 Folder 1: Beyond The American Revolutionary War, articles and excerpts from the following: Wilbur C. Abbott, Charles Francis Adams, Randolph Greenfields Adams, Charles M. Andrews, T. Jefferson Coolidge, Jr., Thomas Anburey, Clarence Walroth Alvord, C.E. Ayres, Robert E. Brown, Fred C. Bruhns, Charles A. Beard and Mary R. Beard, Benjamin Franklin, Carl Lotus Belcher, Henry Belcher, Adolph B. Benson, S.L. Blake, Charles Knowles Bolton, Catherine Drinker Bowen, Julian P. Boyd, Carl and Jessica Bridenbaugh, Sanborn C. Brown, William Hand Browne, Jane Bryce, Edmund C. Burnett, Alice M. Baldwin, Viola F. Barnes, Jacques Barzun, Carl Lotus Becker, Ruth Benedict, Charles Borgeaud, Crane Brinton, Roger Butterfield, Edwin L. Bynner, Carl Bridenbaugh Folder 2: Douglas Campbell, A.F. Pollard, G.G. Coulton, Clarence Edwin Carter, Harry J. Armen and Rexford G. Tugwell, Edward S. Corwin, R. Coupland, Earl of Cromer, Harr Alonzo Cushing, Marquis De Shastelluz, Zechariah Chafee, Jr. Mellen Chamberlain, Dora Mae Clark, Felix S. Cohen, Verner W. Crane, Thomas Carlyle, Thomas Cromwell, Arthur yon Cross, Nellis M. Crouso, Russell Davenport Wallace Evan Daview, Katherine B. -

Nicholas Fanizzi Visual Essay

Nicholas Fanizzi Japanese-American Internment Several times in history a country has turned on its own people. During World War II, Japan was introduced into the war, when they conducted a surprise attack on the United States’ home soil. Japan commenced an air raid on Pearl Harbor claiming the lives of over 2,300 Americans troops. With only one vote against the decision, Congress sent America to war against Japan. The rest of America supported Congress’ decision. The United States was in a full out war with Japan, which included homeland discrimination against the Japanese. Mayor Laguardia of New York took out all of the Japanese from the city and kept them in custody on Ellis Island. This started a nationwide purge of the Japanese race causing Executive Order 9066 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The proclamation authorized the military to exclude people from certain areas and force relocation (“Roosevelt”). This was for people of all foreign races but specifically targeted the Japanese. Although the immediate effects of the attack on Pearl Harbor were traumatic, the homeland reaction included racial segmentation, unjust relocation with internment camps, and stereotyping the Japanese race in America. Source: Theodore Geisel, “Waiting for the Signal From Home,” PM Magazine, February 13, 1942 Children's author Dr. Seuss was a prominent anti-Japanese political cartoonist during World War II. One of his most prominent and popular cartoons was “Waiting for a Signal From Home” published on February 13th, 1942. The attack on Pearl Harbor left people worrying if the Japanese would strike again and left America feeling vulnerable. -

Comment on the Commentary of the Day by Donald J. Boudreaux Chairman, Department of Economics George Mason University [email protected]

Comment on the Commentary of the Day by Donald J. Boudreaux Chairman, Department of Economics George Mason University [email protected] http://www.cafehayek.com Disclaimer: The following “Letters to the Editor” were sent to the respective publications on the dates indicated. Some were printed but many were not. The original articles that are being commented on may or may not be available on the internet and may require registration or subscription to access if they are. Some of the original articles are syndicated and therefore may have appeared in other publications also. 29 August 2010 should do almost the suburbs so that more opposite of what he people can enjoy Editor, Washington advocates. McMansions situated on Examiner large grassy lots. We For example, it's beneficial should quit protecting Dear Editor: to help others. So I argue endangered species that that we are morally obliged humans don't consume as David Sirota identifies a to do more to help others, food, as protecting such benefit - namely, reduced regardless of the costs species hurts people by human impact on the (including any resulting reducing economic output. environment – and argues impacts on the And we should certainly that, therefore, people are environment). avoid Mr. Sirota's practice morally obliged to take of bicycling to work: steps to achieve that We should spend more because travel by bike benefit ("A week of living time working in factories takes far more time than with low impact on the producing furniture, cars, does travel by car, bicycle environment," Aug. 29). cell phones, and the commuters thoughtlessly – But because he ignores countless other products nay, irresponsibly! - reduce competing benefits, Mr. -

The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860

PRESERVING THE WHITE MAN’S REPUBLIC: THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN CONSERVATISM, 1847-1860 Joshua A. Lynn A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Harry L. Watson William L. Barney Laura F. Edwards Joseph T. Glatthaar Michael Lienesch © 2015 Joshua A. Lynn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joshua A. Lynn: Preserving the White Man’s Republic: The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860 (Under the direction of Harry L. Watson) In the late 1840s and 1850s, the American Democratic party redefined itself as “conservative.” Yet Democrats’ preexisting dedication to majoritarian democracy, liberal individualism, and white supremacy had not changed. Democrats believed that “fanatical” reformers, who opposed slavery and advanced the rights of African Americans and women, imperiled the white man’s republic they had crafted in the early 1800s. There were no more abstract notions of freedom to boundlessly unfold; there was only the existing liberty of white men to conserve. Democrats therefore recast democracy, previously a progressive means to expand rights, as a way for local majorities to police racial and gender boundaries. In the process, they reinvigorated American conservatism by placing it on a foundation of majoritarian democracy. Empowering white men to democratically govern all other Americans, Democrats contended, would preserve their prerogatives. With the policy of “popular sovereignty,” for instance, Democrats left slavery’s expansion to territorial settlers’ democratic decision-making. -

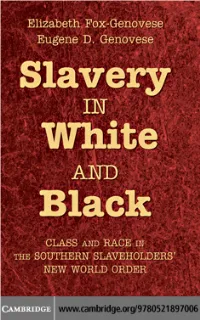

Slavery in White and Black Class and Race in the Southern Slaveholders’ New World Order

This page intentionally left blank Slavery in White and Black Class and Race in the Southern Slaveholders’ New World Order Southern slaveholders proudly pronounced themselves orthodox Chris- tians, who accepted responsibility for the welfare of the people who worked for them. They proclaimed that their slaves enjoyed a better and more secure life than any laboring class in the world. Now, did it not follow that the lives of laborers of all races across the world would be immea- surably improved by their enslavement? In the Old South, but in no other slave society, a doctrine emerged among leading clergymen, politicians, and intellectuals, “Slavery in the Abstract,” which declared enslavement the best possible condition for all labor regardless of race. They joined the socialists, whom they studied, in believing that the free-labor system, wracked by worsening class warfare, was collapsing. A vital question: To what extent did the people of the several social classes of the South accept so extreme a doctrine? That question lies at the heart of this book. Elizabeth Fox-Genovese (1941–2007) was Eleonore Raoul Professor of the Humanities at Emory University, where she was founding director of Women’s Studies. She served on the Governing Council of the National Endowment for the Humanities (2002–2007). In 2003, President George W. Bush awarded her a National Humanities Medal; the Georgia State Senate honored her with a special resolution of appreciation for her contri- butions as a scholar, teacher, and citizen of Georgia; and the fellowship of Catholic Scholars bestowed on her its Cardinal Wright Award. -

Monographien Herausgegeben Vom Deutschen Institut Für Japanstudien Der Philipp Franz Von Siebold Stiftung Band 27, 2000

Monographien Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Institut für Japanstudien der Philipp Franz von Siebold Stiftung Band 27, 2000 Junko Ando Die Entstehung der Meiji-Verfassung Zur Rolle des deutschen Konstitutionalismus im modernen japanischen Staatswesen Monographien aus dem Deutschen Institut für Japanstudien der Philipp Franz von Siebold Stiftung Band 27 2000 Monographien Band 27 Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Institut für Japanstudien der Philipp Franz von Siebold Stiftung Direktorin: Prof. Dr. Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit Anschrift: Nissei Kôjimachi Bldg. Kudan-Minami 3-3-6 Chiyoda-ku Tôkyô 102-0074, Japan Tel.: (03) 3222-5077 Fax: (03) 3222-5420 e-mail: [email protected] Umschlagbild mit freundlicher Genehmigung aus: Mainichi shinbunsha (Hrsg.), Ketteiban Shôwashi, Bd. 2, S. 1, Tôkyô 1984 Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Ando, Junko: Die Entstehung der Meiji-Verfassung : zur Rolle des deutschen Konstitutionalismus im modernen japanischen Staatswesen / Junko Ando. – München : Iudicium-Verl., 2000 (Monographien aus dem Deutschen Institut für Japanstudien der Philipp Franz von Siebold Stiftung ; Bd. 27) Zugl.: Düsseldorf, Univ., Diss., 1999 u. d. T.: Ando, Junko: Über die Entstehungsgeschichte der Meiji-Verfassung ISBN 3-89129-508-1 D 61 © IUDICIUM Verlag GmbH München 2000 Alle Rechte vorbehalten Druck: Offsetdruck Schoder, Gersthofen Printed in Germany ISBN 3-89129-508-1 Vorwort VORWORT Japans Modernisierung in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts nach über zweihundertjähriger weitreichender Isolation ist eins der faszinie- rendsten Kapitel der Weltgeschichte. Dabei war dieser Prozeß, als dessen Ergebnis Japan sich als einziges nichtwestliches Land in den Kreis der modernen Industrienationen einreihte und zum Vorbild vieler Länder der sogenannten Dritten Welt avancierte, von Beginn an durchaus nicht unumstritten. Die der Bevölkerung abverlangten Opfer waren beträcht- lich, und die Meinungen darüber, wie Japan sich gegenüber den westli- chen Mächten am besten behaupten könne, waren gespalten. -

Created By: Sabrina Kilbourne

Created by: Kathy Feltz, Keifer Alternative High School Grade level: 9-12 Special Education Primary Source Citation: (2) “How Some Apprehensive People Picture Uncle Sam After the War,” Detroit News, 1898. (3) “John Bull” by Fred Morgan, Philadelphia Inquirer, 1898. Reprinted in “The Birth of the American Empire as Seen Through Political Cartoons (1896-1905)” by Luis Martinez-Fernandez, OAH Magazine of History, Vol.12, No. 3 Spring, 1998: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25163220. Allow students, in groups or individually, to examine the cartoons while answering the questions below in order. The questions are designed to guide students into a deeper analysis of the source and sharpen associated cognitive skills. Level I: Description 1. What characters do you see in both cartoons? 2. Who is represented by the tall man in both cartoons? How do you know? Give details. 3. Who are represented by the smaller figures in both cartoons? How do you know? Give details. Level II: Interpretation 1. Why is the United States/Uncle Sam pictured as the largest character? 2. Why are the Philippines, Cuba, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico pictured as smaller characters? 3. What concept that we have studied is illustrated in these cartoons? Level III: Analysis 1. What does the first cartoon tell us about the U.S. control over its territories? 2. How does this change in the second cartoon? 3. What do these cartoons tell you about the American feelings towards the people in these territories? “How some apprehensive people picture Uncle Sam after the war.” A standard anti-imperialist argument: acquiring new territories meant acquiring new problems—in this case, the problem of “pacifying” and protecting the allegedly helpless inhabitants. -

SUPERGIRLS and WONDER WOMEN: FEMALE REPRESENTATION in WARTIME COMIC BOOKS By

SUPERGIRLS AND WONDER WOMEN: FEMALE REPRESENTATION IN WARTIME COMIC BOOKS by Skyler E. Marker A Master's paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina May, 2017 Approved by: ________________________ Rebecca Vargha Skyler E. Marker. Supergirls and Wonder Women: Female Representation in Wartime Comics. A Master's paper for the M.S. in L.S. degree. May, 2017. 70 pages. Advisor: Rebecca Vargha This paper analyzes the representation of women in wartime era comics during World War Two (1941-1945) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (2001-2010). The questions addressed are: In what ways are women represented in WWII era comic books? What ways are they represented in Post 9/11 comic books? How are the representations similar or different? In what ways did the outside war environment influence the depiction of women in these comic books? In what ways did the comic books influence the women in the war outside the comic pages? This research will closely examine two vital periods in the publications of comic books. The World War II era includes the genesis and development to the first war-themed comics. In addition many classic comic characters were introduced during this time period. In the post-9/11 and Operation Iraqi Freedom time period war-themed comics reemerged as the dominant format of comics. Headings: women in popular culture-- United States-- History-- 20th Century Superhero comic books, strips, etc.-- History and criticism World War, 1939-1945-- Women-- United States Iraq war (2003-2011)-- Women-- United States 1 I.