F4805 Side a Page 1 F4805 Side A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N

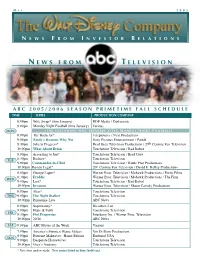

M A Y 2 0 0 5 N E W S F R O M I N V E S T O R R E L A T I O N S N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N A B C 2 0 0 5 / 2 0 0 6 S E A S O N P R I M E T I M E F A L L S C H E D U L E TIME SERIES PRODUCTION COMPANY 8:00pm Wife Swap* (thru January) RDF Media / Diplomatic 9:00pm Monday Night Football (thru January) Various MON ( T H E F O L L O W I N G W I L L P R E M I E R E A F T E R M O N D A Y N I G H T F O O T B A L L ) 8:00pm The Bachelor* Telepictures / Next Productions 9:00pm Emily’s Reasons Why Not Sony Pictures Entertainment / Pariah 9:30pm Jake in Progress* Brad Grey Television Productions / 20th Century Fox Television 10:00pm What About Brian Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 8:00pm According to Jim* Touchstone Television / Brad Grey 8:30pm Rodney* Touchstone Television TUE 9:00pm Commander-in-Chief Touchstone Television / Battle Plan Productions 10:00pm Boston Legal* 20th Century Fox Television / David E. Kelley Productions 8:00pm George Lopez* Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / Fortis Films 8:30pm Freddie Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / The Firm WED 9:00pm Lost* Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 10:00pm Invasion Warner Bros. -

A Christmas Carol’ Time for ‘A Take

HAPPY HOLIDAYS! Inside: Seacoast Holidays ALSO INSIDE: 21 VOICES 26,000 COPIES Please Deliver Before FRIDAY, DECEMBER 1, 2006 Vol. 32 | No. 47 | 2 Sections |40 Pages FIT TO A ‘T’ Karma Threads seeks to help teens with t-shirts BY SCOTT E. KINNEY ATLANTIC NEWS STAFF WRITER EXETER | Positive messages for teens and the chance to help others. That’s the premise behind KarmaThreads — a positive messaging apparel company fusing vintage flair with contemporary design — as Cyan they announced earlier this month the launch of its first line of T-shirts for women of all ages. Magenta With inspirational messages like “Dream,” “Hope,” “Laugh Often,” “Love More,” and other phrases, these hip new T-shirts pro- vide an easy way for all to look good and do good. Inspired by a desire to give back to teens in need, KarmaThreads Yellow founder, Rhonda Lee, is sharing a portion from all of the items sold to charities that shelter and nurture teens. For Lee, it is an idea that has hung around for years and is now Black coming into fruition. “I really wanted to form a non-profit organization for teens to provide clothes for kids in need,” she said. “I think that it’s our responsibility to help these teens that are the next generation and teach them the responsibility of taking care of their own.” On Friday, Nov. 24 — also known as “Black Friday” — eight businesses in Exeter aided in the launch of Kar- maThreads by displaying the T-shirts in their stores and providing purchase information for those who are inter- ested in giving back. -

Written and Directed by Jeremy Podeswa Produced by Robert Lantos Based Upon the Novel by Anne Michaels Runtime: 105 Minutes to D

Written and Directed by Jeremy Podeswa Produced by Robert Lantos Based upon the novel by Anne Michaels Media Contacts: New York Agency: Los Angeles Agency: IDP/Samuel Goldwyn Films Donna Daniels Lisa Danna New York: Amy Johnson Melody Korenbrot Liza Burnett Fefferman Donna Daniels PR Block-Korenbrot, Inc. Jeff Griffith-Perham 20 West 22nd St., Suite 1410 North Market Building Samuel Goldwyn Films New York, NY 1010 110 S. Fairfax Ave., #310 1133 Broadway – Suite 926 T: 347.254.7054 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10010 [email protected] T: 323.634.7001 T: 212.367.9435 [email protected] [email protected] F: 212.367.0853 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] LA: Mimi Guethe T: 310.860.3100 F: 310.860.3198 [email protected] Runtime: 105 minutes To download press notes and photography, please visit: www.press.samuelgoldwynfilms.com USER NAME: press LOG IN: golden! 1 FUGITIVE PIECES THE CAST Jakob Stephen Dillane Athos Rade Sherbedgia Alex Rosamund Pike Michaela Ayelet Zurer Jakob (young) Robbie Kay Ben Ed Stoppard Naomi Rachelle Lefevre Bella Nina Dobrev Mrs. Serenou Themis Bazaka Jozef Diego Matamoros Sara Sarah Orenstein Irena Larissa Laskin Maurice Daniel Kash Ioannis Yorgos Karamichos Allegra Danae Skiadi 2 FUGITIVE PIECES ABOUT THE STORY A powerful and unforgettably lyrical film about love, loss and redemption, FUGITIVE PIECES tells the story of Jakob Beer, a man whose life is transformed by his childhood experiences during WWII. The film is based on the beloved and best-selling novel by Canadian poet Anne Michaels. -

2006 Marketing Advertising

A SUPPLEMENT TO 2006 FACT PACK 4th ANNUAL GUIDE TO ADVERTISING MARKETING Published February 27, 2006 © Copyright 2006 Crain Communications Inc. 2 | Advertising Age | FactPack FactPack | Advertising Age | 3 FACT PACK 2006 CONTENTS TOP LINE DATA ON THE ADVERTISING AND MEDIA INDUSTRIES In a pdf version, click anywhere on the items below to jump directly to the page. GENERAL MOTORS CORP. is the top marketer by ad spending in the U.S. but who ranks Advertising & Marketing first on a global basis? A spot for Fox TV’s American Idol on Wednesdays at prime- Top five U.S. advertisers and their agencies . .6-7 time commands the most dollars per :30 ($518,466), but how much more is that than Top U.S. advertisers . .8 a spot for runner-up CSI:Crime Scene Investigation on CBS-TV the following night? And what about that growth in a Super Bowl :30 spot since the $42,000 average cost Top U.S. megabrands . .9 paid per :30 at Super Bowl I in 1967? Omnicom Group may be the world’s biggest U.S. ad spending totals by media . .10 marketing organization but how do its agency networks stack up against their com- Top U.S. advertisers by media . .11-13 petition? How big and far-reaching are those multifaceted media goliaths? It’s all in Top global marketers and spending in top 10 countries . .14-15 the FactPack, whether in print form on your desk, or a click away on your computer or network. Consumer brand market share leaders in select categories . -

Rampaging Driver Leaves Local Scars a Month After Tragedy, One Victim Is Recovering

NEIGHBORHOOD NEWS FOOD & WINE HOME & GARDEN Hospital plans In the kitchen Cottage gets draw brickbats and on the air a new life Page 3 Page 11 Pages 13 New FILLMORE SAN FRANCISCO ■ OCTOBER 2006 Rampaging Driver Leaves Local Scars A month after tragedy, one victim is recovering B B K R entries for August 29 on Richard Hilkert’s Twell-penciled calendar. One is an appointment for a midday massage — a 78th birthday present from a friend who’s a masseur. 0 e other says simply: Horror. Hilkert, a longtime neighborhood fi xture, was one of more than a dozen local residents run down and injured by an out-of-control driver on August 29. It was a bizarre incident that landed the neighborhood in the national news. Hilkert was returning home from his massage early that Tuesday afternoon when he saw a man lying in the street at Sutter and Steiner. “He was moaning and groaning, and I thought, ‘Oh, there’s some poor fellow who’s down and out,’ ” he says. Others were helping, so Hilkert continued on his way. “I was into the crosswalk, when suddenly this car came right at me — and I joined the other fellow, on my back, in the street,” his glasses and hearing aids scattered, Hilkert recalls. Neighbors and bystanders quickly gathered. “0 en one of them screamed: ‘My God! He’s coming back!’ ” Hilkert says. “I saw the car make a U-turn at Fillmore and come back to fi nish us off .” Selfl ess souls in the crowd dragged Hilkert to safety just as the black SUV sped down the street. -

Reversible Reasoning in Multiplicative Situations: Conceptual

REVERSIBLE REASONING IN MULTIPLICATIVE SITUATIONS: CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS, AFFORDANCES AND CONSTRA1NTS by AJAY RAMFUL (Under the Direction of John Olive) ABSTRACT While previous research studies have focused primarily on the additive structure , relatively fewer attempts have been made to explore the multiplicative structure from a reversibility perspective. The aim of this exploratory study was to investigate, at a fine-grained level of detail, the strategies and constraints that middle-school students encounter in reasoning reversibly in the multiplicative domains of fraction and ratio. In the first phase of the study a mathematical analysis of reversibility situations was conducted. In the second empirical phase, three pairs of above-average students at the grades 6, 7 and 8 were interviewed in a rural middle-school in the United States. Three selected data sets were analyzed using Vergnaud’s theory of the multiplicative conceptual field, the concept of units, and notion of quantitative reasoning. The findings put into perspective the importance of the theorem-in-action as a key element for reasoning reversibly in multiplicative situations. Further, the results show that reversibility is context-sensitive, with the numeric feature of problem parameters being a major factor. Relatively prime numbers and fractional quantities acted as inhibitors preventing the cueing of the invariant ‘division as the inverse of multiplication’, thereby constraining students from reasoning reversibly. Moreover, the form of reversible reasoning was found to be dependent on the type of multiplicative structures. Among others, two key resources were identified as being essential for reasoning reversibly in fractional contexts: interpreting fractions in terms of units, which enabled the students to access their whole number knowledge and secondly, the coordination of 3 levels of units. -

Sweeping Changes Proposed for Immigration to Finland

ISSUE 18 (50) • 9 – 15 MAY 2008 • €3 • WWW.HELSINKITIMES.FI DOMESTIC NEWS BUSINESS LIFESTYLE CULTURE EAT&DRINK Focus Aviation Diplomats’ Ellen Thesleff It’s on waste harmed by life in in Retretti’s brunch prevention expensive fuel Finland summer time! page 4 page 12 page 18 page 21 page 22 LEHTIKUVA / HEIKKI SAUKKOMAA An aging employee needs work and rest in a suitable relation TERHI LEINIÖ – STT pervisors and continuous adminis- MICHAEL NAGLER – HT trative changes decreased the work satisfaction of the elderly. EVEN a few extra free days would Maija-Kaarina Saloranta, 73, help the elderly to cope with their has remained eager to work even work. Most of the respondents in a during retirement. “I work because recent survey by the Rehabilitation it’s fun. Working also provides you Foundation and the UKK Institute with a routine and brings vigour to do not necessarily want semi-re- your everyday life. Otherwise life tirement. Instead they want a slack- would be just reading Helsingin Sa- ening in work schedules. nomat,” she sums up. Rehabilitation Foundation senior Saloranta, who lives in Helsin- researcher Tiina Pensola’s proposed ki, retired at 65 from Yleisradio in age-related free time could be a pre- 2000 but she still participates in the ventive measure with which more publishing of an organisation mag- people could keep on working long- azine and her voice can be heard in er without fatigue and burnout. commercials and in the voice books “Age-related free time would be of the Finnish Federation of the Vis- more affordable for the employer, ually Impaired. -

Emily Abbott '19 Executive Development Assistant, Sony

Emily Abbott ’19 Executive Development Assistant, Sony Pictures Studios Emily Abbott recently graduated from UCLA with a B.A. in english, a concentration in creative writing, and a Minor in film & television. Emily now works on the Sony Lot for a production company titled Counterbalance Entertainment, where she assists Dina Hillier, Jon Hurwitz, Josh Heald, and Hayden Schlossberg. Counterbalance currently has multiple projects in development at networks such as TBS, FOX, and Hulu. During her time at UCLA, Emily interned at New Horizons Picture Corp, Route One Entertainment, The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, and Sony Pictures Television, respectively. Emily was a Writer’s PA for Cobra Kai Season 3. Carlos Adame ’06 CEO, Piñata Farms Erik Akutagawa ’94 Senior Program Manager, Ticketmaster Erik Akutagawa has been a leader in the entertainment and media industry for more than two decades. Most recently, Erik served as senior program manager for Fox and the NFL. Prior to that, Erik was the digital image resources manager at Rhythm & Hues Studios, where he led Academy Award winning teams on projects such as the feature film Life of Pi. Erik has won two Academy Awards (in 2013 and 2008) and three Scientific and Technical Academy Awards (in 2016, 2011 and 2008) Kean Almryde ’09 Manager, Media Network Synergy, Walt Disney Parks & Resorts Kean Almryde as Associate Manager for Media Network Synergy enjoys sharing the stories and magical vacation experiences of storytellers known for their work in television and film. His Disney career started in 2010 as a member of Radio Disney’s Rockin’ Road Crew. -

The SPE Reel D

FEBRUARY 2006 ISSUE 2 SONY PICTURES ENTERTAINMENT WANTS YOU TO KNOW IN GLOBAL MOTION PICTURE MARKETPLACE, SONY SPEAKS Contents MANY LANGUAGES 1 IN GLOBAL MOTION PICTURE Much of the focus of Sony Pictures’ motion The strategy was also intended to allow MARKETPLACE, SONY SPEAKS MANY picture production and distribution Sony Pictures the opportunity to work with LANGUAGES operations is on those films produced in the some of the most talented actors and United States. While awareness of these filmmakers in the world. Local language MICHAEL & AMY WANT YOU TO KNOW 1 operations is broad, many people don’t productions are intended for release in the 2005: The Year in Review realize that Sony Pictures is also the only territories where they are produced and, major studio to maintain stand-alone, local where appropriate, are distributed on a IN THE SPOTLIGHT 3 language motion picture production units wider basis, including the United States. Directing Sony’s Multicultural Vision throughout Europe, Asia and Latin America. In fact, Sony Pictures has been at the Gareth Wigan, Vice Chairman, Columbia 4 THE WORLD OF SPE: TriStar Motion Picture Group (CTMPG), DIVISIONAL UPDATES forefront of bringing local language blockbusters to the global marketplace. heads up this line of business for the Sony Pictures Television . .4 Company. He works very closely with Paul Motion Pictures . .4 Recognizing that the international market Smith, Executive Vice President, CTMPG, Sony Pictures Television International . .4 was growing faster than the domestic Worldwide Marketing and Distribution, Sony Pictures Home Entertainment . .4 market for theatrical releases, Sony Pictures Amy Pascal, Jeff Blake, the international Sony Pictures Digital . -

Locals' Input for Allman

Community Pet of the week FORUM sports digest ..........Page A-3 Our readers write .......Page B-1 ...............................A-4 INSIDE Mendocino County’s World briefly The Ukiah local newspaper ..........Page 2 Tomorrow: Partly sunny 7 58551 69301 0 MONDAY Jan. 8, 2007 50 cents tax included DAILY JOURNAL ukiahdailyjournal.com 16 pages, Volume 148 Number 274 email: [email protected] Two new bills could provide federal relief to California The Daily Journal “It is our responsibility to do everything we ued to deteriorate, forcing the Pacific financial assistance is a top priority this year.” In the first two days of the new legislative can to help the thousands of families and busi- Fisheries Management Council to reduce the There is also an expectation that the com- session, two companion bills were introduced, nesses that are suffering from the largest com- fishing seasons in 2005 and 2006. As a result, mercial salmon season will be significantly that if passed, would provide federal disaster mercial salmon fishery disaster in our nation’s the commercial fishing season was cut by reduced in 2007, Thompson said. relief to California and Oregon’s fishing history,” Thompson said. “The devastating more than 90 percent in 2006, costing fishing “We can not allow one disastrous salmon industry. impact this disaster has had on California’s families and associated fishing businesses season to turn into a long-term tragedy, yet North Coast has been obvious for years, and it more than $60 million. that is what will happen if we don't take The legislation -- SB 145 authored by Sen. -

Disney Channel Reinforces Our Belief That Digital Distribution Can Broaden Audiences

MARCH 2007 Q1 FY07 SELECTED EARNINGS REMARKS “The keys to Disney’s success are the quality of our content, consumer affinity for our brands and our ability to leverage creative success across the scope of our businesses. Our company-wide focus on these competencies has resulted in the earnings growth, strong cash flow and improving returns you’ve seen us deliver for four straight years now and will, we believe, always remain at the core of Disney’s success.” For further detail, continue to page 3… DISNEY ANNOUNCES EXPANSION OF CRUISE BUSINEss Disney plans to expand its cruise business by adding two new ocean liners. Scheduled to launch in 2011 and 2012, the ships will more than double the passenger capacity for Disney Cruise Line. For further detail, continue to page 7… BRAND NEW DISNEY.COM RELEASED Disney.com, the number one online entertainment destination for kids and parents, has launched an updated version with exciting new features for Disney fans of all ages. The new Disney.com is a result of a company-wide effort to create a broadband-centric, category-breaking online experience that delivers highly personalized entertainment offerings that appeal to a broad audience of kids, parents and Disney fans. For further detail, continue to page 13… DISNEY RENAMES VIDEO GAME BUSINEss UNIT At its investor conference, Disney recently announced the renaming of its video game business unit to Disney Interactive Studios. For further detail, continue to page 14… TOUCHSTONE TELEVISION NOW ABC TELEVISION STUDIO The Disney-ABC Television Group will rename its in-house production company, Touchstone Television, as the ABC Television Studio, it was announced recently at the 2007 Disney Investor Conference by Anne Sweeney, co-chair, Disney Media Networks and president, Disney-ABC Television Group. -

Bo B Ig E R Be C O M E S Th E Si X T H Ceo I N Di S N E Y's

O C T O B E R 2 0 0 5 N E W S F R O M I N V E S T O R R E L A T I O N S BO B IG E R BE C O M E S TH E SI X T H CEO I N DI S N E Y ’S 8 2 - Y E A R HI S T O R Y On October 2, 2005, Bob Iger succeeded Michael Eisner as CEO of The Walt Disney Company. Robert (Bob) A. Iger, the sixth CEO in The Walt Disney Company’s 82-year history, was appointed to this post after the Company’s board of directors elected him to succeed Michael D. Eisner in March, 2005. Previously, Bob served as President and Chief Operating Officer of The Walt Disney Company, a position he had held since June, 2000. In this role, he partnered with Michael Eisner in overseeing all aspects of the Company’s worldwide operations including its filmed entertainment, theme parks and resorts, media networks and consumer products businesses. He also became a member of Disney’s board of directors at this time. Bob Iger began his career at ABC in 1974. Over the last 31 years, he has held a series of increasingly respon- sible senior management positions at the Company, including serving as President and Chief Operating Officer of Capital Cities/ABC, where he guided the complex merger of ABC with The Walt Disney Company. During his years with ABC, Bob oversaw its broadcast television network and station, cable television, radio and publishing businesses, which includes the market leading brands of ABC, ESPN, Lifetime, A&E and The History Channel.