A Collection of Vignettes from South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring the Uptake of Genetically Modified White Maize by Smallholder Farmers: the Case of Hlabisa, South Africa

Exploring the uptake of genetically modified white maize by smallholder farmers: The case of Hlabisa, South Africa Mankurwana H Mahlase MHLMAN031 Town Cape A dissertation submitted in full fulfilmentof of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Science in Environmental and Geographical Science University Faculty of Science University of Cape Town October 2016 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town COMPULSORY DECLARATION This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature: Date: ii Abstract The use of genetically modified (GM) crops to resolve food security and poverty issues has been met with controversy and scepticism. The rationale for this research was to highlight the nuanced reasons as to why smallholder farmers are motivated to use agricultural biotechnology. The aim of this study was to explore the uptake of GM maize by South African smallholder farmers in order to contribute towards understanding the implications of agricultural biotechnology in smallholder agriculture. Using the case studies of Hlabisa in KwaZulu-Natal, the objectives were; (i) to investigate the perceived benefits and problems associated with the uptake of GM maize. -

Third World Network

TWN Third World Network November 19, 2020 Director-General Qu Dongyu UN Food and Agriculture Organization Viale delle Terme di Caracalla 00153 Rome, Italy Dear Director-General Qu Dongyu, The 350 civil society and Indigenous Peoples organizations from 63 countries listed below represent hundreds of thousands of farmers, fisherfolk, agricultural workers and other communities, as well as human rights, faith-based, environmental and economic justice institutions. We are writing to express our deep concern over your stated plans to strengthen official ties with CropLife International. We strongly urge you to reconsider this alliance. Deepening collaboration with CropLife, a trade association representing the interests of corporations which produce and promote dangerous pesticides, directly undermines FAO’s priority of minimising the harms of chemical pesticide use worldwide, “including the progressive ban of highly hazardous pesticides (HHPs).” It also undermines the principles set out in FAO’s Code of Conduct on Pesticide Management, and ties the agency with producers of harmful, unsustainable chemical technologies — relinquishing FAO’s role as a global leader supporting innovative approaches to agricultural production that promote the progressive realization of the right to adequate food in the context of national food security, sustainability and resilience. Reliance on hazardous pesticides is a short-term fix that undermines the rights to adequate food and health for present and future generations, as stated in the 2017 report of the Special Rapporteur on the right to food. A recent analysis of industry records documents that CropLife members, BASF, Bayer Crop Science, Corteva Agriscience, FMC and Syngenta, make more than one-third of their sales income from HHPs — the pesticides that are most harmful to human health and the environment. -

DISTRICT ECONOMIC PROFILES Umkhanyakude District 2021

Office of the Head of Department 270 Jabu Ndlovu Street, Pietermaritzburg, 3201 Tel: +27 (33) 264 2515, Fax: 033 264 2680 Private Bag X 9152 Pietermaritzburg, 3200 www.kznded.gov.za DISTRICT ECONOMIC PROFILES UMkhanyakude District 2021 GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION UMkhanyakude DM (DC 27) Population: 686,908 Area Size: 13, 855.3 Km2 Location: Located along the coast in the far north of the KZN Province, it shares its borders with Swaziland and Mozambique, as well as with the districts of Zululand and King Cetshwayo. It consists of the following four local municipalities: uMhlabuyalingana, Jozini, Big 5 Hlabisa and Mtubatuba. The Isimangaliso Wetland Park, is encompassed in the district and it holds a number of biodiversity and conservation areas attracting a number of tourists to the region. DISTRICT SPATIAL FEATURES UMkhanyakude District Municipality is located in the far north eastern corner of the province. The district is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east and Mozambique and Swaziland to the north, as well as two KZN districts to the south and west. The district shares international borders with two countries: Mozambique in the north and Swaziland along its north-western boundary. The Lubombo SDI corridor (MR439) was upgraded in the late 1990s to a tar road – extending from Hluhluwe through to Mbazwana to join the only other tar road in the region at Pelindaba, before heading north east through KwaNgwanase (Manguzi) to the Mozambique border at Farazel. The dominant land tenure of the district is communal tenure under Ingonyama Trust lands. The only privately owned commercial farms lie in a narrow strip along the N2 from Mtubatuba to Mkuze. -

The Convention on Biological Diversity: Biodiversity, Access and Benefit-Sharing

SANBI Biodiversity Series 3 The Convention on Biological Diversity: biodiversity, access and benefit-sharing. A resource for learners (Grades 10–12) by Anastelle Solomon & Paul Le Grange Pretoria 2006 SANBI Biodiversity Series The South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) was established on 1 September 2004 through the signing into force of the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act (NEMBA) No. 10 of 2004 by President Thabo Mbeki. The Act expands the mandate of the former National Botanical Institute to include responsibilities relating to the full diversity of South Africa’s fauna and flora, and builds on the internationally respected programmes in conservation, research, education and visitor services developed by the National Botanical Institute and its predecessors over the past century. The vision of SANBI is to be the leading institution in biodiversity science in Africa, facilitating conservation, sustainable use of living resources, and human well-being. SANBI’s mission is to promote the sustainable use, conservation, ap- preciation and enjoyment of the exceptionally rich biodiversity of South Africa, for the benefit of all people. SANBI Biodiversity Series will publish occasional reports on projects, technologies, workshops, symposia and other activities initiated by or executed in partnership with SANBI. Illustrations: Tano September Technical editor: Emsie du Plessis Design & layout: Daleen Maree Cover design: Daleen Maree How to cite this publication SOLOMON, A. & LE GRANGE, P. 2006. The Convention on Biological Diversity: biodiversity, access and benefit-sharing. A resource for learners (Grades 10–12). SANBI Biodiversity Series 3. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. ISBN 1-919976-31-0 © Published by: South African National Biodiversity Institute Obtainable from: SANBI Bookshop, Private Bag X101, Pretoria, 0001 South Africa. -

Umkhanyakude Development Agency Strategic Plan 2019-2024

UMKHANYAKUDE DEVELOPMENT AGENCY STRATEGIC PLAN 2019-2024 UMDA STRATEGIC PLAN 2019-2024 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 2 1.1. BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2. THE MANDATE OF UMHLOSINGA DEVELOPMENT AGENCY ..................................................................... 3 2. THE STRATEGIC PLAN 2019-2024 ..................................................................................................... 4 2.1. CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE NEXT 5 YEARS .................................................................... 5 2.2. VISION, GOALS AND OBJECTIVES .............................................................................................................. 9 2.3. GUIDING PRINCIPLE ................................................................................................................................ 10 2.4. CATALYTIC PROJECTS AND ACTIONS ....................................................................................................... 11 3. IMPLEMENTATION STRUCTURES ........................................................................................... 20 3.1. ORGANISING FOR IMPLEMENTATION ..................................................................................................... 20 3.2. FUNDING MODEL ................................................................................................................................... -

Genetically Modified Crops in Africa: Implications for Small Farmers

Genetically Modified Crops in Africa: Implications for Small Farmers Devlin Kuyek August 2002 Implications for Small Farmers About this Briefing This briefing was researched and written by Devlin Contents Kuyek for Genetic Resources Action International (GRAIN) and a group of NGOs that aim to raise awareness about the implications of genetic engineering and intellectual property rights for 1. INTRODUCTION 1 small farmers in Africa. These NGOs include SACDEP (Kenya), RODI (Kenya), Biowatch (South Africa), ISD (Ethiopia), Jeep (Uganda), CTDT (Zimbabwe), Pelum (Regional, Southern 2. THE PAST PREDICTS THE FUTURE 1 Africa), ITDG (International), Gaia Foundation (International) and ActionAid (International). Did Africa miss a revolution? 1 The briefing looks at the push to bring GM crops and technologies to Africa and tries to sort out what Africa’s Green Revolution 2 the implications will be for Africa’s small farmers. It especially focuses on the situation in East and Southern Africa. The briefing does not share the 3. THE FORCES BEHIND THE CROPS 4 optimism of the proponents of genetic engineering. Rather, it views genetic engineering as an extension Who are the crop pushers? 4 of the Green Revolution paradigm that failed to address the needs of Africa’s small farmers and served only to exacerbate their problems. 4. TRUSTING THE ‘EXPERTS’ 7 The many groups and individuals who gave time and information to the preparation of this paper Bt Cotton and biosafety 10 are gratefully acknowledged. Comments on the paper may be addressed to Devlin Kuyek at [email protected] 5. SURELY THERE’S A BETTER WAY? 13 Published in August 2002, by Genetic Resources Action International (GRAIN): Sweeter potatoes without biotech 13 Girona 25, pral, Barcelona 08010, Spain Tel: +34 933 011 381 Bt Maize: Big companies working for Fax: +34 933 011 627 big farmers 15 Email: [email protected] 1 Web: www.grain.org Green Revolution, Gene Revolution .. -

Reconnaissance Study UAP Phase 2 UKDM

UNIVERSAL ACCESS PLAN (FOR WATER SERVICES) PHASE 2 PROGRESSIVE DEVELOPMENT OF A REGIONAL CONCEPT PLAN - UMKHANYAKUDE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY CONTRACT NO. 2015/178 RECONNAISSANCE STUDY FINAL JUNE 2016 Prepared for: Compiled by: Umgeni Water BIGEN AFRICA Services (Pty) Ltd 310 Burger Street, PMB Block B, Bellevue Campus, PO Box 9, PMB 5 Bellevue Road, Kloof, 3610 Tel: (033) 341 1111 PO Box 1469, Kloof, 3640 Fax: (033) 341 1084 Tel: +27(0) 31 717 2571 Attention: Mr Vernon Perumal Fax: +27(0) 31 717 2572 e-mail: [email protected] Enquiries: Ms Aditi Lachman In Association with: Universal Access Plan for Water Services Phase 2 Reconnaissance Study - uMkhanyakude District Municipality June 2016 REPORT CONTROL PAGE Report Control Client: Umgeni Water Project Name: Universal Access Plan (For Water Services) Phase 2: Progressive Development of a Regional Concept Plan Project Stage: Reconnaissance Study Report title: Progressive Development of a Regional Concept Plan – UKDM: Reconnaissance Study Report status: Final Project reference no: 2663-00-00 Report date: June 2016 Quality Control Written by: Njabulo Bhengu – Bigen Africa Reviewed by: Aditi Lachman – Bigen Africa Approved by: Robert Moffat – Bigen Africa Date: June 2016 Document Control Version History: Version Date changed Changed by Comments F:\Admin\2663\Reconnaissance Study Reports\UKDM\Reconnaissance Study_UAP Phase 2_UKDM_FINAL.docx i Universal Access Plan for Water Services Phase 2 Reconnaissance Study - uMkhanyakude District Municipality June 2016 Water Availability EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Water for domestic and commercial usage within the district is sourced from both surface and This report is the Reconnaissance Study for the Universal Access Plan Phase 2 – Progressive groundwater. -

Protected Area Management Plan: 2011

Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa Protected Area Management Plan: 2011 Prepared by Udidi Environmental Planning and Development Consultants and Ezemvelo KwaZulu-Natal Wildlife Protected Area Management Planning Unit Citation: Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife. 2011. Protected Area Management Plan: Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park, South Africa. Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, Pietermaritzburg. TABLE OF CONTENT 1. PURPOSE AND SIGNIFICANCE OF HIP: ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 PURPOSE ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 SIGNIFICANCE ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 2. ADMINISTRATIVE AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK ...................................................................................................... 4 2.1 INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS ....................................................................................................................... 4 2.4 LOCAL AGREEMENTS, LEASES, SERVITUDE ARRANGEMENTS AND MOU’S .......................................................... 6 2.5 BROADENING CONSERVATION LAND USE MANAGEMENT AND BUFFER ZONE MANAGEMENT IN AREAS SURROUNDING HIP ............................................................................................................................................ 7 3. BACKGROUND -

Maurice Webb Race Relations Unit

MAURICE WEBB RACE RELATIONS UNIT A DIRECTORY OF RURAL AND PERI-URBAN COMMUNITY BASED ORGANISATIONS IN NATAL T Mzimela CENTRE FOR SOCIAL AND DEVELOPMENT STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF NATAL KING GEORGE V AVENUE DURBAN 4001 SOUTH AFRICA * CENTRE FOR SOCIAL AND DEVELOPMENT STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF NATAL DURBAN A DIRECTORY OF RURAL AND PERI-URBAN COMMUNITY BASED ORGANISATIONS IN NATAL PRODUCED BY T. MZIMELA MAURICE WEBB RACE RELATIONS UNIT CENTRE FOR SOCIAL AND DEVELOPMENT STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF NATAL DURBAN The Centre for Social and Development Studies was established in 1988 through the merger of the Centre for Applied Social Science and the Development Studies Unit. The purpose of the centre is to focus university research in such a way as to make it relevant to the needs of the surrounding developing communities, to generate general awareness of development problems and to assist in aiding the process of appropriate development planning. ISBN No 1-86840-029-8 RURAL AND PERI-URBAN COMMUNITY BASED ORGANIZATIONS This Directory consists of rural COMMUNITY BASED ORGANISATIONS (CBOS) and some organisations from peri-urban areas in Natal. It has been produced by the Maurice Webb Race Relations Unit at the Centre for Social and development Studies which is based at the University of Natal. The directory seeks to facilitate communication amongst community based organisations in pursuance of their goals. The province is divided into five zones : (i) ZONE A: UPPER NOTUERN NATAL REGION: This includes the Mahlabathini, Nquthu, Nhlazatshe, Nongoma and Ulundi districts. (ii) ZONE B: UPPER NORTHERN NATAL COASTAL REGION: This includes Ingwavuma, Kwa-Ngwanase, Hlabisa, Mtubatuba, Empangeni, Eshowe, Mandini, Melmoth, Mthunzini, and Stanger districts. -

Statement from the Seed and Knowledge Seminar Salt Rock, Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa 13-15 September, 2016

STATEMENT FROM THE SEED AND KNOWLEDGE SEMINAR SALT ROCK, KWAZULU-NATAL, SOUTH AFRICA 13-15 SEPTEMBER, 2016 A CALL TO REVIVE, RESTORE AND STRENGTHEN FARMER-LED SEED SYSTEMS Seed is the very essence of life. It is central to our diverse cultures and spiritualities, foods, ecologies, knowledge systems and economies. But seed is under siege. It has been colonised and commodified by elite interests that support and promote destructive industrial agriculture, which is costing the Earth. While industrial agriculture feeds less than a third of the world’s population, it monopolises our land and water. This system − with its monocultures, hybrid and genetically modified seeds, chemical inputs and high fossil fuel consumption − is a leading contributor to climate change and environmental degradation. It creates unhealthy communities, poisoning us and filling our stomachs with corrupt calories, mostly devoid of nutrients. It also undermines and marginalises the diverse smallholder farming systems that have nourished us for centuries, creating economic dependencies and locking farmers into cycles of debt. It is rapidly being viewed as an outdated approach that is unable to respond to the changes the world is facing. Our vision, together with that of millions of farmers, consumers and citizens across the world, is for our food production systems to revive and enhance tried and tested methods that are low-carbon and low-input in nature; to preserve and regenerate resources rather than destroy them; and to support diverse and small-scale farming systems. This movement affirms and advocates for a world where agriculture is productive and sustainable, where food is nutritious and culturally appropriate, and where farmer-led seed and knowledge systems are valued and supported. -

Export This Category As A

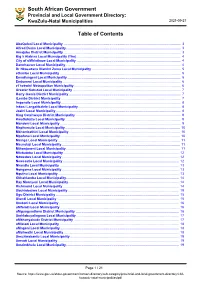

South African Government Provincial and Local Government Directory: KwaZulu-Natal Municipalities 2021-09-27 Table of Contents AbaQulusi Local Municipality .............................................................................................................................. 3 Alfred Duma Local Municipality ........................................................................................................................... 3 Amajuba District Municipality .............................................................................................................................. 3 Big 5 Hlabisa Local Municipality (The) ................................................................................................................ 4 City of uMhlathuze Local Municipality ................................................................................................................ 4 Dannhauser Local Municipality ............................................................................................................................ 4 Dr Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma Local Municipality ................................................................................................ 5 eDumbe Local Municipality .................................................................................................................................. 5 Emadlangeni Local Municipality .......................................................................................................................... 6 Endumeni Local Municipality .............................................................................................................................. -

Spatial-Temporal Mapping of Parthenium (P. Hysterophorul) in the Mtubatuba Municipality, Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa

Spatial-temporal mapping of Parthenium (P. HysterophoruL) in the Mtubatuba municipality, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa Lwando Royimani 212559726 A thesis presented to the School of Agricultural, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Sciences. Supervisor: Prof. Onisimo Mutanga Co-Supervisor: Dr. John Odindi Pietermaritzburg, South Africa November 2017 i Abstract Detecting and mapping the occurrence, spread, and abundance of Alien Invasive Plants (AIPs) have recently gained substantial attention, globally. Therefore, the present study aims to assess remote sensing application for mapping the spatial and temporal spread of Parthenium (P. HysterophoruL) in the Mtubatuba municipality of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Parthenium is an aggressive herbaceous plant from the South and Central America that has colonized many regions of the world including Asia, Australia, and Africa. The adverse social, economic and ecological impacts of the plant have emphasized the need for a robust control programme to combat its spread. However, data for the management of the weed has been gathered by means of manual methods such as field surveys which are time and labour intensive. Alternatively, remote sensing techniques provides cost effective approach to large-scale mapping of AIPs. The first objective of the study provides an overview of advancements in satellite remote sensing for mapping AIPs spread and the associated challenges and opportunities. Satellite remote sensing techniques have been successful in detecting and mapping of AIPs, exploring their spatial and temporal distribution in rangeland ecosystems. Although they provide fine spatial information, the excessive image acquisition costs associated with the use of high spatial and hyperspectral datasets are a limitation to continuous and large-scale mapping of AIPs.