Foundations for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glaadawards March 16, 2013 New York New York Marriott Marquis

#glaadawards MARCH 16, 2013 NEW YORK NEW YORK MARRIOTT MARQUIS APRIL 20, 2013 LOS AnGELES JW MARRIOTT LOS AnGELES MAY 11, 2013 SAN FRANCISCO HILTON SAN FRANCISCO - UnION SQUARE CONNECT WITH US CORPORATE PARTNERS PRESIDENT’S LETTer NOMINEE SELECTION PROCESS speCIAL HONOrees NOMINees SUPPORT FROM THE PRESIDENT Welcome to the 24th Annual GLAAD Media Awards. Thank you for joining us to celebrate fair, accurate and inclusive representations of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community in the media. Tonight, as we recognize outstanding achievements and bold visions, we also take pause to remember the impact of our most powerful tool: our voice. The past year in news, entertainment and online media reminds us that our stories are what continue to drive equality forward. When four states brought marriage equality to the election FROM THE PRESIDENT ballot last year, GLAAD stepped forward to help couples across the nation to share messages of love and commitment that lit the way for landmark victories in Maine, Maryland, Minnesota and Washington. Now, the U.S. Supreme Court will weigh in on whether same- sex couples should receive the same federal protections as straight married couples, and GLAAD is leading the media narrative and reshaping the way Americans view marriage equality. Because of GLAAD’s work, the Boy Scouts of America is closer than ever before to ending its discriminatory ban on gay scouts and leaders. GLAAD is empowering people like Jennifer Tyrrell – an Ohio mom who was ousted as leader of her son’s Cub Scouts pack – to share their stories with top-tier national news outlets, helping Americans understand the harm this ban inflicts on gay youth and families. -

Additional Documents to the Amicus Brief Submitted to the Jerusalem District Court

בבית המשפט המחוזי בירושלים עת"מ 36759-05-18 בשבתו כבית משפט לעניינים מנהליים בעניין שבין: 1( ארגון Human Rights Watch 2( עומר שאקר העותרים באמצעות עו"ד מיכאל ספרד ו/או אמילי שפר עומר-מן ו/או סופיה ברודסקי מרח' דוד חכמי 12, תל אביב 6777812 טל: 03-6206947/8/9, פקס 03-6206950 - נ ג ד - שר הפנים המשיב באמצעות ב"כ, מפרקליטות מחוז ירושלים, רחוב מח"ל 7, מעלות דפנה, ירושלים ת.ד. 49333 ירושלים 9149301 טל: 02-5419555, פקס: 026468053 המכון לחקר ארגונים לא ממשלתיים )עמותה רשומה 58-0465508( ידיד בית המשפט באמצעות ב"כ עו"ד מוריס הירש מרח' יד חרוצים 10, ירושלים טל: 02-566-1020 פקס: 077-511-7030 השלמת מסמכים מטעם ידיד בית המשפט בהמשך לדיון שהתקיים ביום 11 במרץ 2019, ובהתאם להחלטת כב' בית המשפט, מתכבד ידיד בית המשפט להגיש את ריכוז הציוציו של העותר מס' 2 החל מיום 25 ליוני 2018 ועד ליום 10 למרץ 2019. כפי שניתן להבחין בנקל מהתמצית המצ"ב כנספח 1, בתקופה האמורה, אל אף טענתו שהינו "פעיל זכויות אדם", בפועל ציוציו )וציוציו מחדש Retweets( התמקדו בנושאים שבהם הביע תמיכה בתנועת החרם או ביקורת כלפי מדינת ישראל ומדיניותה, אך נמנע, כמעט לחלוטין, מלגנות פגיעות בזכיות אדם של אזרחי מדינת ישראל, ובכלל זה, גינוי כלשהו ביחס למעשי רצח של אזרחים ישראלים בידי רוצחים פלסטינים. באשר לטענתו של העותר מס' 2 שחשבון הטוויטר שלו הינו, בפועל, חשבון של העותר מס' 1, הרי שגם כאן ניתן להבין בנקל שטענה זו חסרת בסיס כלשהי. ראשית, החשבון מפנה לתפקידו הקודם בארגון CCR, אליו התייחסנו בחוות הדעת המקורית מטעם ידיד בית המשפט בסעיף 51. -

1 Via Email December 6, 2018 Richard M. Englert Office of The

Via Email December 6, 2018 Richard M. Englert Office of the President Temple University Second Floor, Sullivan Hall 1330 Polett Walk Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122 Re: Investigation of Marc Lamont Hill for United Nations Speech Dear President Englert: As civil rights organizations seeking to protect the constitutional rights of people speaking out for Palestinian freedom, we write to express concerns about Temple University’s reported investigation of Professor Marc Lamont Hill after his November 28th speech at the United Nations calling for equality for all people in Israel and Palestine. Hill’s speech is protected by the First Amendment, by which Temple University is bound as a public university. Temple’s failure to disclaim trustee Patrick O’Connor’s demand for investigation into Hill impermissibly chills the free speech rights of professors, as well as the entire university community. This letter offers additional context to help Temple University avoid stifling expression of political views with which some may disagree. I. Facts The following summarizes the events leading up to O’Connor’s request that Temple’s legal department investigate options for disciplining Hill. Please let us know if you believe the factual summary to be inaccurate. a. Hill’s Social Justice Background Marc Lamont Hill has been a professor at Temple University since 2005 and is currently Steve Charles Professor of Media, Cities, and Solutions.1 Alongside his academic work, he has also played a prominent role in public discourse, having hosted news programs on BET and VH1 and served as a commentator on CNN and Fox News.2 His writing and scholarship have touched on diverse and vital issues of social justice including youth education, gentrification, criminal 1 BIO - Dr. -

FALL 2020 Distribution and Sales

FALL 2020 Distribution and Sales U.S. Distribution and Sales: Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, For all other markets: Two Rivers Distribution India General international inquiries (previously called Perseus Distribution) Shawn Abraham Ingram Publisher Services International 1400 Broadway, Suite 520 Manager, International Sales 1400 Broadway, Suite 520 New York, NY 10018 Ingram Publisher Services International New York, NY 10018 1400 Broadway, Suite 520 [email protected] Orders and Customer Service: New York, NY 10018 Ingram Content Group LLC +1 (212) 581-7839 tel International Orders One Ingram Blvd. [email protected] Please send orders and remittances to: La Vergne, TN 37086 IPS_International.Orders@ (866) 400-5351 tel Australia ingramcontent.com [email protected] NewSouth Books Orders and Distribution This catalog describes books to be United Kingdom, Ireland 15-23 Helles Avenue published from September 2020 General Enquiries: Moorebank, NSW 2170 through February 2021 INGRAM UK Australia 5th Floor +61 (2) 8778 9999 tel The New Press 52–54 St John Street +61 (2) 8778 9944 fax 120 Wall Street, Fl 31 Clerkenwell [email protected] New York, NY 10005-4007 London (212) 629-8802 tel EC1M 4HF South Africa (212) 629-8617 fax [email protected] Jonathan Ball Elmasie Stodart www.thenewpress.com Office C4, The District Ordering Information: 41 Sir Lowry Road For media/event inquiries, NBNi/INGRAM Woodstock, Cape Town 7925 please contact: 1 Deltic Avenue South Africa [email protected] Rooksley +27 (0) 21 469 8932 Milton Keynes +27 (0) 86 270 0825 For special sales and bulk orders, 01752 202301 Queries: please contact: [email protected] [email protected] (212) 629-8802 tel Orders: [email protected] Canada [email protected] Canadian Manda Group Cover image by Shutterstock 664 Annette Street, Toronto, ON M6S India Ordering Information Page 16 photograph by Bob Miller/Redux 2C8 Penguin Books India Pvt. -

Page 1 of 279 FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS

FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS. January 01, 2012 to Date 2019/06/19 TITLE / EDITION OR ISSUE / AUTHOR OR EDITOR ACTION RULE MEETING (Titles beginning with "A", "An", or "The" will be listed according to the (Rejected / AUTH. DATE second/next word in title.) Approved) (Rejectio (YYYY/MM/DD) ns) 10 DAI THOU TUONG TRUNG QUAC. BY DONG VAN. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 DAI VAN HAO TRUNG QUOC. PUBLISHER NHA XUAT BAN VAN HOC. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 POWER REPORTS. SUPPLEMENT TO MEN'S HEALTH REJECTED 3IJ 2013/03/28 10 WORST PSYCHOPATHS: THE MOST DEPRAVED KILLERS IN HISTORY. BY VICTOR REJECTED 3M 2017/06/01 MCQUEEN. 100 + YEARS OF CASE LAW PROVIDING RIGHTS TO TRAVEL ON ROADS WITHOUT A APPROVED 2018/08/09 LICENSE. 100 AMAZING FACTS ABOUT THE NEGRO. BY J. A. ROGERS. APPROVED 2015/10/14 100 BEST SOLITAIRE GAMES. BY SLOANE LEE, ETAL REJECTED 3M 2013/07/17 100 CARD GAMES FOR ALL THE FAMILY. BY JEREMY HARWOOD. REJECTED 3M 2016/06/22 100 COOL MUSHROOMS. BY MICHAEL KUO & ANDY METHVEN. REJECTED 3C 2019/02/06 100 DEADLY SKILLS SURVIVAL EDITION. BY CLINT EVERSON, NAVEL SEAL, RET. REJECTED 3M 2018/09/12 100 HOT AND SEXY STORIES. BY ANTONIA ALLUPATO. © 2012. APPROVED 2014/12/17 100 HOT SEX POSITIONS. BY TRACEY COX. REJECTED 3I 3J 2014/12/17 100 MOST INFAMOUS CRIMINALS. BY JO DURDEN SMITH. APPROVED 2019/01/09 100 NO- EQUIPMENT WORKOUTS. BY NEILA REY. REJECTED 3M 2018/03/21 100 WAYS TO WIN A TEN-SPOT. BY PAUL ZENON REJECTED 3E, 3M 2015/09/09 1000 BIKER TATTOOS. -

View Bad Ideas About Writing

BAD IDEAS ABOUT WRITING Edited by Cheryl E. Ball & Drew M. Loewe BAD IDEAS ABOUT WRITING OPEN ACCESS TEXTBOOKS Open Access Textbooks is a project created through West Virginia University with the goal of produc- ing cost-effective and high quality products that engage authors, faculty, and students. This project is supported by the Digital Publishing Institute and West Virginia University Libraries. For more free books or to inquire about publishing your own open-access book, visit our Open Access Textbooks website at http://textbooks.lib.wvu.edu. BAD IDEAS ABOUT WRITING Edited by Cheryl E. Ball and Drew M. Loewe West Virginia University Libraries Digital Publishing Institute Morgantown, WV The Digital Publishing Institute believes in making work as openly accessible as possible. Therefore, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. This license means you can re-use portions or all of this book in any way, as long as you cite the original in your re-use. You do not need to ask for permission to do so, although it is always kind to let the authors know of your re-use. To view a copy of this CC license, visit http://creative- commons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. This book was set in Helvetica Neue and Iowan Old Style and was first published in 2017 in the United States of America by WVU Libraries. The original cover image, “No Pressure Then,” is in the public domain, thanks to Pete, a Flickr Pro user. -

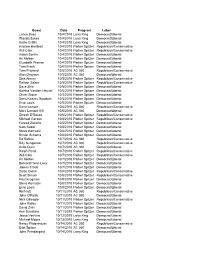

Guest Date Program Label Lance Bass 10/4/2010 Larry King

Guest Date Program Label Lance Bass 10/4/2010 Larry King Democrat/Liberal Wanda Sykes 10/4/2010 Larry King Democrat/Liberal Kathy Griffin 10/4/2010 Larry King Democrat/Liberal Andrew Breitbart 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Will Cain 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Aaron Sorkin 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Ari Melber 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Elizabeth Warren 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Tom Frank 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Tom Prichard 10/5/2010 AC 360 Republican/Conservative Alan Grayson 10/5/2010 AC 360 Democrat/Liberal Dick Armey 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Reihan Salam 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Dave Zirin 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Katrina Vanden Heuvel 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Oliver Stone 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Doris Kearns Goodwin 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Errol Louis 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Dana Loesch 10/6/2010 AC 360 Republican/Conservative Marc Lamont Hill 10/6/2010 AC 360 Democrat/Liberal Dinesh D'Souza 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Michael Gerson 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Fareed Zakaria 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Sam Seder 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Steve Kornacki 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Simon Schama 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Ed Rollins 10/7/2010 AC 360 Republican/Conservative Billy Nungesser 10/7/2010 -

Institutional Decolonization: Toward a Comprehensive Black Politics

NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW VOLUME 20.1 INSTITUTIONAL DECOLONIZATION: TOWARD A COMPREHENSIVE BLACK POLITICS A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW VOLUME 20.1 INSTITUTIONAL DECOLONIZATION: TOWARD A COMPREHENSIVE BLACK POLITICS A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS National Political Science Review | ii THE NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW EDITORS Managing Editor Tiffany Willoughby-Herard University of California, Irvine Duchess Harris Macalester College Sharon D. Wright Austin The University of Florida Angela K. Lewis University of Alabama, Birmingham BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Brandy Thomas Wells Oklahoma State University EDITORIAL RESEARCH ASSISTANTS Lisa Beard Armand Demirchyan LaShonda Carter Amber Gordon Ashley Daniels Deshanda Edwards EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Melina Abdullah—California State University, Los Angeles Keisha Lindsey—University of Wisconsin Anthony Affigne—Providence College Clarence Lusane—American University Nikol Alexander-Floyd—Rutgers University Maruice Mangum—Alabama State University Russell Benjamin—Northeastern Illinois University Lorenzo Morris—Howard University Nadia Brown—Purdue University Richard T. Middleton IV—University of Missouri, Niambi Carter—Howard University St. Louis Cathy Cohen—University of Chicago Byron D’Andra Orey—Jackson State University Dewey Clayton—University of Louisville Marion Orr—Brown University Nyron Crawford—Temple University Dianne Pinderhughes—University of Notre Dame Heath Fogg Davis—Temple University Matt Platt—Morehouse College Pearl Ford Dowe—University of Arkansas H.L.T. Quan—Arizona State University Kamille Gentles Peart—Roger Williams University Boris Ricks—California State University, Northridge Daniel Gillion—University of Pennsylvania Christina Rivers—DePaul University Ricky Green—California State University, Sacramento Neil Roberts—Williams College Jean-Germain Gros—University of Missouri, St. -

Impact of a Pandemic and Social Injustice on Access and Equity in Education Friday, March 5, 2021, at 9:30 A.M

Center for Access, Success & Equity (CASE) presents 2021 CASE VIRTUAL SUMMIT Impact of a Pandemic and Social Injustice on Access and Equity in Education Friday, March 5, 2021, at 9:30 a.m. Faculty, students and administrators The 2021 CASE Summit will in education are experiencing feature expert practitioners and unprecedented academic challenges leading voices in education who due to COVID-19 and social justice will share valuable research and struggles. The dual pandemic has recommendations for those created many challenges in regard to committed and engaged in the access and equity in education. development of education. KEYNOTE SPEAKERS GUEST PRESENTERS Angel Santiago Dr. Fabienne Doucet New Jersey William T. Grant Dr. Marc Lamont Hill Dan Habib Teacher of the Year Foundation officer Professor, author and Award-winning filmmaker social justice activist FACULTY MODERATORS Registration and information: Dr. Tyrone W. McCombs [email protected] JOIN ZOOM MEETING Meeting ID: 817 5181 1514 Dr. Susan Browne Dr. Beth Wassell Dr. Cory Dixon Erica Watson Dr. Qian Sun Dr. Brent Elder Passcode: 839980 Brown One tap mobile +13017158592,,81751811514#,,,, *839980# US (Washington DC) The CASE Virtual Summit is open to all members of the University and our educational partners. +13126266799,,81751811514#,,,, SPONSORS: College of Education, CASE, Diversity In Action Committee (DIA) and Department *839980# US (Chicago) of Interdisciplinary & Inclusive Education (IIE) 21-023 2021 CASE VIRTUAL SUMMIT SCHEDULE OPENING & WELCOME He has worked on campaigns to KEYNOTE SPEAKER II: 9:30 – 10 a.m. end the death penalty, abolish DAN HABIB prisons and release numerous Dr. Gaetane Jean-Marie Creating a Culture of Inclusion political prisoners. -

October 2014 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data

October 2014 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data October 5, 2014 29 men and 5 women NBC's Meet the Press with Chuck Todd: 4 men and 1 woman Dan Pfeiffer (M) Reince Priebus (M) Jim Webb (M) David Axelrod (M) Dr. Nancy Snyderman (F) CBS's Face the Nation with Bob Schieffer: 7 men and 1 woman Dr. Anthony Fauci (M) Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (M) House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy (M) Rep. Elijah Cummings (M) Anthony Salvato (M) Jonathan Martin (M) Nancy Cordes (F) John Dickerson (M) ABC's This Week with George Stephanopoulos: 4 men and 1 woman Dr. Tom Frieden (M) Van Jones (M) Peggy Noonan (F) Mark Halperin (M) John Heilemann (M) CNN's State of the Union with Candy Crowley: 8 men and 0 women Dr. Tom Frieden (M) Dr. William Frohna (M) Sen. Lindsey Graham (M) Sen. Jack Reed (M) Bill Daley (M) Andrew Card (M) Mack McLarty (M) Ken Duberstein (M) Fox News' Fox News Sunday with Chris Wallace: 5 men and 2 women Dr. Anthony Fauci (M) Sen, Kelly Ayotte (F) Dan Bogino (M) Brit Hume (M) Julie Pace (F) George Will (M) Juan Williams (M) October 12, 2014 28 men and 13 women NBC's Meet the Press with Chuck Todd: 6 men and 5 women Susan Rice (F) Richard Engel (M) Henry Kissinger (M) James Baker (M) Kathleen Parker (F) David Brody (M) Helene Cooper (F) Robert Gibbs (M) Sara Fagen (F) Tom Brokaw (M) Helene Cooper (F) CBS's Face the Nation with Bob Schieffer: 6 men and 2 women Leon Panetta (M) Rep. -

A Free Palestine from the River to the Sea”: the 9 Dirty Words You Can’T Say (On T.V

Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 7 Issue 1 Article 6 2019 “A Free Palestine from the River to the Sea”: The 9 Dirty Words You Can’t Say (on T.V. or Anywhere Else) Bryant W. Sculos Worcester State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Recommended Citation Sculos, Bryant W. (2019) "“A Free Palestine from the River to the Sea”: The 9 Dirty Words You Can’t Say (on T.V. or Anywhere Else)," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.7.1.008322 Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol7/iss1/6 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “A Free Palestine from the River to the Sea”: The 9 Dirty Words You Can’t Say (on T.V. or Anywhere Else) Abstract This piece was originally published with The Hampton Institute and republished with Monthly Review. The firing of Prof. Marc Lamont Hill from CNN for pro-Palestinian comments he made during a speech at the U.N.--and the subsequent targeting of Hill for firing yb a trustee at Temple University where he is a tenured professor--represents a broader silencing of critics of US imperialism, global capitalism, and settler colonialism in the mainstream media and academia. -

The Road to the White (Nationalist) House: Coded Racial Appeals in Donald Trump's Presidential Campaign

Duke University The Road to the White (Nationalist) House: Coded Racial Appeals in Donald Trump’s Presidential Campaign i Table of Contents Preface............................................................................................................................................. ii 1. “Dog Whistle Politics”: Coded Racial Appeals in American Political Discourse..................... 1 a. Dog Whistling Dixie: George Wallace and his Political Descendants............................. 2 b. Donald Trump: Dog Whistle or Dog Scream?................................................................15 2. Sounding the Dog Whistle: Anti-Immigrant, Anti-Muslim, and Anti-Black.......................... 20 a. Anti-Immigrant: “The Latino Threat”............................................................................ 20 b. Anti-Muslim: “Radical Islamic Terrorism”.................................................................... 40 c. Anti-Black: Crime, Welfare, and the African American Other...................................... 49 3. Why the Whistle Worked: White Nationalist Postracialism and White Identity Politics........ 62 a. White Nationalist Postracialism...................................................................................... 63 b. “Wink Wink Wink”: Coded Appeals to White Nationalism.......................................... 75 c. White Identity Politics and the Post-Racial Illusion....................................................... 82 Conclusion....................................................................................................................................