Masters in Management in Entrepreneurship and New Venture Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Private Placement Activity Chris Hastings | [email protected] | 917-621-3750 3/5/2018 – 3/9/2018 (Transactions in Excess of $20 Million)

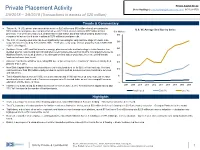

Private Capital Group Private Placement Activity Chris Hastings | [email protected] | 917-621-3750 3/5/2018 – 3/9/2018 (Transactions in excess of $20 million) Trends & Commentary ▪ This week, 14 U.S. private placement deals between $20 million and $50 million closed, accounting for U.S. VC Average Deal Size by Series $516 million in total proceeds, compared to last week’s 10 U.S. deals leading to $357 million in total $ in Millions proceeds. This week also had 5 U.S. deals between $50 million and $100 million yielding $320 million, $35 compared to last week’s 4 deals resulting in $279 million in total proceeds. ▪ The U.S. VC average deal size has been significantly increasing for early and late stage VC deals. Late $30 stage VC has increased by 8.8% CAGR 2008 – 2017 while early stage VC has grown by 7.4% CAGR 2008 – 2017. (see figure) ▪ Southern Cross, a PE fund that invests in energy, pharmaceuticals and technology in Latin America, has $25 decided against restructuring its third fund after receiving some interest from its LPs. It is largely because its third fund has been a weak performer, the discount on fund stakes would have been steep and that the $20 fund wanted more time to exit. ▪ Univision has filed to withdraw its pending IPO due to “prevailing market conditions”. Univision initially filed $15 plans to IPO in 2015. ▪ New State Capital Partners has closed its second institutional fund on its $255 million hard cap. The fund $10 can invest more than $50 million equity per deal in sectors such as business services, healthcare services and industrials. -

Click to Edit Master Title Style

Click to edit Master title style Secondary VIII, L.P. April 14th 2016 Dallas Police & Fire Pension System FirmClick Overviewto edit Master title style Year firm Assets under Number of Number of fund founded management direct investments investments 2000 $2B 175 215 San Francisco Firm Distributions headquarters Number of professionals to Paid-In Capital Firm net IRR 2 offices 17 82%* 21% TWO COMPLEMENTARY FUND STRATEGIES SECONDARY LIQUIDITY PARTNERSHIP HOLDINGS • Secondary direct and secondary fund investments in • Fund and direct investments in early and late-stage venture-backed companies mid-stage venture-backed companies • Typically $20 - $200 million in revenues at time of • Typically pre-revenue to $20 million in investment revenues at time of investment • Seeking high IRR • Seeking high multiple All data is unaudited and estimated as of 9/30/15. *As of 10/21/2015. Aggregate track records are net of fees, expenses and carried interest paid to the general partner entity of each respective fund. Prior performance is not a guarantee 2 of future returns. Please see slide 15 for detailed track record information and a full list of funds. OurClick Team to edit Master title style FIRM MANAGEMENT FINANCE & INVESTOR RELATIONS HANS SWILDENS ROBERT MAY AARON HINZ LENA McNULTY LISA BREIMAN Founder & CEO COO & CCO Controller Investor Relations Investor Relations Speedera, Microline Founders Fund, Mohr Davidow, Thomas Weisel | Venrock Santa Clara University University of Denver UCSB | Columbia MBA Thomas Weisel PricewaterhouseCoopers San Jose State -

NVCA 2021 YEARBOOK Data Provided by Dear Readers

YEARBOOK Data provided by Credits & Contact National Venture Capital Association NVCA Board of Directors 2020-2021 (NVCA) EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Washington, DC | San Francisco, CA nvca.org | [email protected] | 202-864-5920 BARRY EGGERS Lightspeed Venture Partners, Venture Forward Chair Washington, DC | San Francisco, CA MICHAEL BROWN Battery Ventures, Chair-Elect ventureforward.org | [email protected] JILL JARRETT Benchmark, Treasurer ANDY SCHWAB 5AM Ventures, Secretary BOBBY FRANKLIN President and CEO PATRICIA NAKACHE Trinity Ventures, At-Large JEFF FARRAH General Counsel EMILY MELTON Threshold Ventures, At-Large JUSTIN FIELD Senior Vice President of Government MOHAMAD MAKHZOUMI NEA, At-Large Affairs MARYAM HAQUE Executive Director, Venture AT-LARGE Forward MICHAEL CHOW Research Director, NVCA and PETER CHUNG Summit Partner Venture Forward DIANE DAYCH Granite Growth Health Partners STEPHANIE VOLK Vice President of Development BYRON DEETER Bessemer Venture Partners RHIANON ANDERSON Programs Director, Venture SCOTT DORSEY High Alpha Forward RYAN DRANT Questa Capital CHARLOTTE SAVERCOOL Senior Director of PATRICK ENRIGHT Longitude Capital Government Affairs STEVE FREDRICK Grotech Ventures MICHELE SOLOMON Director of Administration CHRIS GIRGENTI Pritzker Group Venture Capital DEVIN MILLER Manager of Communications and JOE HOROWITZ Icon Ventures Digital Strategy GEORGE HOYEM In-Q-Tel JASON VITA, Director of Programming and CHARLES HUDSON Precursor Ventures Industry Relations JILL JARRETT Benchmark JONAS MURPHY Manager of Government Affairs -

Bloomberg Briefs

Wednesday June 8, 2016 www.bloombergbriefs.com MedMen Seeks $100 Million for Marijuana Investments QUOTED BY AINSLIE CHANDLER, BLOOMBERG BRIEF Medical cannabis management company MedMen is raising its first institutional fund "This is the toughest decision- as it tries to capitalize on investors' interest in legal marijuana enterprises. making environment that I MedMen is trying to raise $100 million for MedMen Opportunity Fund, according to think we have ever been in.... firm founder and Chief Executive Adam Bierman. Yesterday, JPMorgan comes MedMen, founded in 2009, previously acted as a management company for out and they say there is a 36 businesses with medical marijuana licenses. It also invested money from family offices and venture funds in special purpose vehicles where the investors held the cannabis percent chance of a licenses, Bierman said in a May 26 interview. recession. As a CIO or head Existing investors pushed the firm to raise a fund to allow for greater diversification in of private equity, what do you their portfolios, he said. do with that?" “If you are a multi-billion dollar family office or an institutional quality investor, you are — Glenn Youngkin, President and COO of not making one-off investments in the $3 million to $5 million range with single-asset Carlyle Group, at a conference June 7 exposure in a market that is complicated from a regulatory environment,” Bierman said. The Los Angeles-based firm held a first close on the WEEK IN NUMBERS fund in May and hopes to have a final close within six months, Bierman said. $13.5 billion — Extra return MedMen The fund will invest in cannabis-related projects, he Calstrs calculates it earned from its said. -

Piper Jaffray Cybersecurity Earnings Update

Piper Jaffray Cybersecurity Earnings Update Third Quarter 2017 Marc Steifman Greg Klancher Co-Head of Technology Principal Investment Banking Piper Jaffray & Co. Piper Jaffray & Co. MINNEAPOLIS | BOSTON | CHICAGO | HOUSTON | LONDON | LOS ANGELES | NEW YORK | SAN FRANCISCO | ZÜRICH Piper Jaffray Companies (NYSE: PJC) is an investment bank and asset management firm headquartered in Minneapolis with offices across the U.S. and in London, Zurich and Hong Kong. Securities brokerage and investment banking services are offered in the United States through Piper Jaffray & Co., member NYSE and SIPC, in Europe through Piper Jaffray Ltd., authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority, and in Hong Kong through Piper Jaffray Hong Kong, authorized and regulated by the Securities and Futures Commission. Asset management products and services are offered through three separate investment advisory affiliates registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission: Advisory Research Inc., Piper Jaffray Investment Management LLC and PJC Capital Partners LLC. Piper Jaffray & Co., Member SIPC and FINRA 11/17 Piper Jaffray Case Study: Vista Equity Partners acquires majority stake in Jamf Vista Equity Partners: Undisclosed . Vista Equity Partners is a U.S.-based investment firm with more than $30 billion in cumulative capital commitments, currently invests in software, data and technology-enabled organizations. The firm invests in middle market management and leveraged buyouts, growth and acquisition Has purchased a majority financing, recapitalizations, private transactions, spin-outs and corporate divestitures. stake in . The firm was founded in 2000 and is headquartered in Austin, Texas. Jamf: . Jamf focuses on helping businesses, education and government organizations succeed with November 2017 Apple through its Jamf Pro and Jamf Now solutions. -

2018 REPORT POWER POINT Oct 2 from Kelley

Holt-MM&K-Buyouts Insider PE/VC Compensation Report Current Trends in Design and Levels of Compensation in the Private Equity and Venture Capital Industry 2018-2019 Preview Table of Contents Survey Background I. Introduction/Participant Summary 1 Key Findings 2 The 2018-2019 Holt-MM&K-Buyouts Insider Scope and Methodology 8 Private Equity and Venture Capital About the Authors 13 Compensation Report is a joint effort of three parties. They are compensation consultants Holt II. Financial and Operational Data 15 Private Equity Consultants and MM&K; and Committed Capital and Cost of Investments 16 global private equity publisher Buyouts Insider. Number of Funds Managed and Number of Portfolio Companies 17 It is jointly written by Michael Holt, David M. Ownership Structure 18 Toll and Joseph Weitemeyer. Management Fees/Other Fees/Fee Ratios/Fee Splits 19 Copyright Information III. Human Capital 23 Data and information in this report is copyrighted by Number of Employees per Employee Group 24 the authors. Electronic and printed copies of this Staffing Changes 2017/2018 25 report can only be shared with employees of the firm Investment Manager Ratios (Capital/Fees/Portfolio Companies) 27 purchasing the report. Users are forbidden to Human Capital Policies/Years to Partner/ MBA Hiring & Compensation 28 reproduce, republish, redistribute, or resell any materials from this report to any party who is not Payroll Cost and Total Employees 29 employed at the organization purchasing the report in either machine-readable form or any other form IV. Compensation Strategy 31 without permission of the authors. No part of this Types of Compensation 32 report may be copied, photocopied, duplicated or Salary & Bonus Changes 34 forwarded in any form or by any means without the Annual Bonus Plans 38 publisher’s written consent. -

NYC Healthcare Venture Capital Report

2020 New York City Healthcare Venture Capital Report INTRODUCTION Welcome to the third annual New York City Healthcare Venture Capital Report. 2019 marked the ten-year anniversary of NYC Health We also explore key trends that are driving investment, Business Leaders (NYCHBL), during which we have seen interest and excitement including: a decade of incredible growth for NYC health start-ups. When Dr. Yin Ho and I co-founded NYCHBL in 2009, • LIFE SCIENCES. A decade ago, it was hard to name our goal was to build an organization that would help any biotechs calling NYC home. Today it’s a vastly connect people passionate about healthcare, because different story as you’ll learn from our dedicated section we believed that NYC should be at the center of on the sector’s growth. (See pages 16-19) healthcare innovation given our many assets. Ten years, • DIGITAL THERAPEUTICS. An emerging area that 55 events and 250 speakers later, New York City has in marries therapeutics with technology to drive better fact become the epicenter of tech-driven healthcare. It’s patient outcomes, digital therapeutics (DTx) are gaining rewarding that we’ve been able to play a part in the traction. As we hear from leaders in this exciting growth story. space, DTx are poised to change clinical practice The 2020 report reflects your overwhelming response, and alter the way healthcare is delivered in the future. inspiring feedback and thoughtful commentary to last (See pages 12-13) year’s report. There are more expert insights, observations • INVESTOR LANDSCAPE. Interest in investing and interviews from leading entrepreneurs, investors and in health has gone far beyond the names we have advisors. -

JAFCO Group / 8595

JAFCO Group / 8595 COVERAGE INITIATED ON: 2020.08.26 LAST UPDATE: 2021.01.28 Shared Research Inc. has produced this report by request from the company discussed in the report. The aim is to provide an “owner’s manual” to investors. We at Shared Research Inc. make every effort to provide an accurate, objective, and neutral analysis. In order to highlight any biases, we clearly attribute our data and findings. We will always present opinions from company management as such. Our views are ours where stated. We do not try to convince or influence, only inform. We appreciate your suggestions and feedback. Write to us at [email protected] or find us on Bloomberg. Research Coverage Report by Shared Research Inc. JAFCO Group/ 8595 RCoverage LAST UPDATE: 2021.01.28 Research Coverage Report by Shared Research Inc. | https://sharedresearch.jp INDEX How to read a Shared Research report: This report begins with the trends and outlook section, which discusses the company’s most recent earnings. First-time readers should start at the business section later in the report. Executive summary ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Key financial data ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 Recent updates ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Trends and outlook -

Private Placement Activity 10/9/2017 – 10/13/2017 (Transactions in Excess of $20 Million) Trends & Commentary $ in Billions

Chris Hastings | [email protected] | 917-621-3750 Private Placement Activity 10/9/2017 – 10/13/2017 (Transactions in excess of $20 million) Trends & Commentary $ in Billions . There has been an increase in the number of $100 million+ VC rounds; 2017 is on pace to see the highest number U.S. VC Deals yet, with more than 61 deals of $100 million or more, raising a combined total of $17.7 billion for deals of $100 10,444 million or more. 10,432 9,226 . Belgian Post Group has agreed to acquire Radial for $820 million. Radial, an e-Commerce logistics company, 8,637 could serve as a tool for Belgian Post Group to compete with Amazon’s growing presence. 7,872 . While the number of U.S. VC deals has been steadily declining YoY, the amount of total VC investments is on 6,734 track to set a decade-high record due to increased deal sizes. (see figure) 5,948 5,381 . Buyout funds on at least $5 billion have seen a large increase. GTCR has just closed its largest buyout fund at 4,696 4,458 $5.3 billion. The fund, GTCR XII will focus on several sectors such as business services, health care, media and fintech. With the closing of this fund, there have now been 9 U.S. firms to close a buyout fund on at least $5 billion $79.2 $69.6 $71.8 in 2017, the most of any year in the past decade. American Securities will follow suit, as it has also set a $6 billion $61.4 target for its newest flagship vehicle. -

Surdna Foundation, Inc

Surdna Foundation, Inc. Financial Statements and Supplemental Information Years Ended June 30, 2017 and 2016 The report accompanying these financial statements was issued by BDO USA, LLP, a Delaware limited liability partnership and the U.S. member of BDO International Limited, a UK company limited by guarantee. Surdna Foundation, Inc. Financial Statements and Supplemental Information Years Ended June 30, 2017 and 2016 Surdna Foundation, Inc. Contents Independent Auditor’s Report 3-4 Financial Statements: Statements of Financial Position as of June 30, 2017 and 2016 5 Statements of Activities for the Years Ended June 30, 2017 and 2016 6 Statements of Functional Expenses for the Years Ended June 30, 2017 and 2016 7 Statements of Cash Flows for the Years Ended June 30, 2017 and 2016 8 Notes to Financial Statements 9-18 Supplemental Information: Schedule of Investments Held at June 30, 2017 19-25 Schedule of Grants Payable at June 30, 2017 26-38 2 Tel: 212-885-8000 100 Park Avenue Fax: 212-697-1299 New York, NY 10017 www.bdo.com Independent Auditor’s Report Board of Directors Surdna Foundation, Inc. New York, New York We have audited the accompanying financial statements of Surdna Foundation, Inc. (the “Foundation”), which comprise the statements of financial position as of June 30, 2017 and 2016, and the related statements of activities, functional expenses and cash flows for the years then ended, and the related notes to the financial statements. Management’s Responsibility for the Financial Statements Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these financial statements in accordance with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America; this includes the design, implementation, and maintenance of internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error. -

Click to Edit Master Title Style

Click to edit Master title style Partnership Holdings IV, L.P. April 14th 2016 Dallas Police & Fire Pension System FirmClick Overviewto edit Master title style Year firm Assets under Number of Number of fund founded management direct investments investments 2000 $2B 175 215 San Francisco Firm Distributions headquarters Number of professionals to Paid-In Capital Firm net IRR 2 offices 17 82%* 21% TWO COMPLEMENTARY FUND STRATEGIES SECONDARY LIQUIDITY PARTNERSHIP HOLDINGS • Secondary direct and secondary fund investments in • Fund and direct investments in early and late-stage venture-backed companies mid-stage venture-backed companies • Typically $20 - $200 million in revenues at time of • Typically pre-revenue to $20 million in investment revenues at time of investment • Seeking high IRR • Seeking high multiple All data is unaudited and estimated as of 9/30/15. *As of 10/21/2015. Aggregate track records are net of fees, expenses and carried interest paid to the general partner entity of each respective fund. Prior performance is not a guarantee 2 of future returns. Please see slide 15 for detailed track record information and a full list of funds. OurClick Team to edit Master title style FIRM MANAGEMENT FINANCE & INVESTOR RELATIONS HANS SWILDENS ROBERT MAY AARON HINZ LENA McNULTY LISA BREIMAN Founder & CEO COO & CCO Controller Investor Relations Investor Relations Speedera, Microline Founders Fund, Mohr Davidow, Thomas Weisel | Venrock Santa Clara University University of Denver UCSB | Columbia MBA Thomas Weisel PricewaterhouseCoopers San -

Rangatira Investments Annual Report 2021

ANNUAL REPORT 2021 www.rangatira.co.nz ANNUAL MEETING of SHAREHOLDERS Monday 26th July 2021, 4.30pm KPMG Level 9 10 Customhouse Quay Wellington COMPANY Level 8, Equinox House 111 The Terrace Wellington 6011 New Zealand PO Box 804 Wellington 6140 New Zealand Telephone +64 4 472 0251 Email [email protected] www.rangatira.co.nz CONTENTS 4 Investing in New Zealand’s future 5 Investment Performance 6 Chairman & CEO’s Report 14 Board of Directors 16 Executive Team 17 Private Investments 25 Rangatira Group at a Glance 26 Public Investments 27 Managed Funds 28 J R McKenzie Trust 30 Charitable Shareholders 32 Financial Statements 67 Independent Auditor’s Report 69 Supplementary Information 73 Appendix 74 Directory COVER IMAGE CREDIT TAKEN BY STUDENTS OF BATTEN 660, OUTWARD BOUND NZ. THIS PAGE IMAGE COURTESY OF OUTWARD BOUND NZ 4 Rangatira Annual Report 2021 INVESTING IN NEW ZEALAND’S FUTURE Founded in 1937, Rangatira Investments has a proud history of investing in leading New Zealand companies. In the 84 years since J R McKenzie established Rangatira, we have been a key investor in many iconic New Zealand businesses over a wide cross-section of industry sectors. We believe in partnering with the best business leaders to We manage our investments with shareholders at the forefront generate both dividend income and asset growth. With a of our thinking – many of these being charitable trusts that permanent asset base, we invest for the long-term alongside would find it harder to make their own unique contribution to business owners to build superior companies and brands.