An Introduction to Litearatue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benchmark Literacy Overview Common Core Edition

BENCHMARK BENCHMARK LITERACYTM LITERACYTM GRADE TM Why choose Benchmark Literacy over K–6 all the other K–6 reading programs? Overview Common Core Edition Common Core Edition • Ten comprehension-focused units per grade • Grade-specific leveled text collections with explicit model-guide-apply instruction organized by unit comprehension strategy Needs • Seamless, spiraling, whole- to small-group • Phonics and word study kits that provide instruction that supports curriculum standards a complete K –6 continuum of skills • Pre-, post-, and ongoing assessment that • Research-proven instructional design Vocabulary drives instruction Shared Reading Phonics & Word Study Fluency Word Study Phonics Independent Reading Comprehensionp K–6 Comprehensive Teacher Resource Systems Assessment & Instruction $95.00 Y13229 B e n c h m a r k e d u c a t i o n c o m p a n y B e n c h m a r k e d u c a t i o n c o m p a n y ® ® BENCHMARK LITERACY OverviewTM Benchmark education company 629 Fifth Avenue • Pelham, NY • 10803 ©2014 Benchmark Education Company, LLC. All rights reserved. Teachers may photocopy the reproducible pages for classroom use. No other part of the guide may be reproduced or transmitted in whole or in part in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN: 978-1-4509-9670-9 For ordering information, call Toll-Free 1-877-236-2465 or visit our website at www.benchmarkeducation.com. BENCHMARK LITERACYTM Overview Common Core Edition Table of Contents Introducing Benchmark Literacy for Grades K–6 . -

017 Harvard Classics

THE HARVARD CLASSICS The Five-Foot Shelf of Books soldier could see through the window how the peopL were hurrying out of the town to see him hanged —P«ge 354 THE HARVARD CLASSICS EDITED BY CHARLES W. ELIOT, LL.D. Folk-Lore and Fable iEsop • Grimm Andersen With Introductions and No/« Volume 17 P. F. Collier & Son Corporation NEW YORK Copyright, 1909 BY P. F. COLLIER & SON MANUFACTURED IN U. *. A. CONTENTS ^SOP'S FABLES— PAGE THE COCK AND THE PEARL n THE WOLF AND THE LAMB n THE DOG AND THE SHADOW 12 THE LION'S SHARE 12 THE WOLF AND THE CRANE 12 THE MAN AND THE SERPENT 13 THE TOWN MOUSE AND THE COUNTRY MOUSE 13 THE FOX AND THE CROW 14 THE SICK LION 14 THE ASS AND THE LAPDOG 15 THE LION AND THE MOUSE 15 THE SWALLOW AND THE OTHER BIRDS 16 THE FROGS DESIRING A KING 16 THE MOUNTAINS IN LABOUR 17 THE HARES AND THE FROGS 17 THE WOLF AND THE KID 18 THE WOODMAN AND THE SERPENT 18 THE BALD MAN AND THE FLY 18 THE FOX AND THE STORK 19 THE FOX AND THE MASK 19 THE JAY AND THE PEACOCK 19 THE FROG AND THE OX 20 ANDROCLES 20 THE BAT, THE BIRDS, AND THE BEASTS 21 THE HART AND THE HUNTER 21 THE SERPENT AND THE FILE 22 THE MAN AND THE WOOD 22 THE DOG AND THE WOLF 22 THE BELLY AND THE MEMBERS 23 THE HART IN THE OX-STALL 23 THE FOX AND THE GRAPES 24 THE HORSE, HUNTER, AND STAG 24 THE PEACOCK AND JUNO 24 THE FOX AND THE LION 25 1 2 CONTENTS PAGE THE LION AND THE STATUE 25 THE ANT AND THE GRASSHOPPER 25 THE TREE AND THE REED 26 THE FOX AND THE CAT 26 THE WOLF IN SHEEP'S CLOTHING 27 THE DOG IN THE MANGER 27 THE MAN AND THE WOODEN GOD 27 THE FISHER 27 THE SHEPHERD'S -

Aesop's Fables

1-21 22-42 The Cock and the Pearl The Frog and the Ox The Wolf and the Lamb Androcles The Dog and the Shadow The Bat, the Birds, and the Beasts The Lion's Share The Hart and the Hunter The Wolf and the Crane The Serpent and the File The Man and the Serpent The Man and the Wood The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse The Dog and the Wolf The Fox and the Crow The Belly and the Members The Sick Lion The Hart in the Ox-Stall The Ass and the Lapdog The Fox and the Grapes The Lion and the Mouse The Horse, Hunter, and Stag The Swallow and the Other Birds The Peacock and Juno The Frogs Desiring a King The Fox and the Lion The Mountains in Labour The Lion and the Statue The Hares and the Frogs The Ant and the Grasshopper The Wolf and the Kid The Tree and the Reed The Woodman and the Serpent The Fox and the Cat The Bald Man and the Fly The Wolf in Sheep's Clothing The Fox and the Stork The Dog in the Manger The Fox and the Mask The Man and the Wooden God The Jay and the Peacock The Fisher 43-62 63-82 The Shepherd's Boy The Miser and His Gold The Young Thief and His Mother The Fox and the Mosquitoes The Man and His Two Wives The Fox Without a Tail The Nurse and the Wolf The One-Eyed Doe The Tortoise and the Birds Belling the Cat The Two Crabs The Hare and the Tortoise The Ass in the Lion's Skin The Old Man and Death The Two Fellows and the Bear The Hare With Many Friends The Two Pots The Lion in Love The Four Oxen and the Lion The Bundle of Sticks The Fisher and the Little Fish The Lion, the Fox, and the Beasts Avaricious and Envious The Ass's Brains -

Aesop's Fables, However, Includes a Microsoft Word Template File for New Question Pages and for Glos- Sary Pages

1 æsop’s fables Click here to jump to the Table of Contents 2 Copyright 1993 by Adobe Press, Adobe Systems Incorporated. All rights reserved. The text of Aesop’s Fables is public domain. Other text sections of this book are copyrighted. Any reproduction of this electronic work beyond a personal use level, or the display of this work for public or profit consumption or view- ing, requires prior permission from the publisher. This work is furnished for informational use only and should not be construed as a commitment of any kind by Adobe Systems Incorporated. The moral or ethical opinions of this work do not necessarily reflect those of Adobe Systems Incorporated. Adobe Systems Incorporated assumes no responsibilities for any errors or inaccuracies that may appear in this work. The software and typefaces mentioned on this page are furnished under license and may only be used in accordance with the terms of such license. This work was electronically mastered using Adobe Acrobat software. The original composition of this work was created using FrameMaker. Illustrations were manipulated using Adobe Photoshop. The display text is Herculanum. Adobe, the Adobe Press logo, Adobe Acrobat, and Adobe Photoshop are trade- marks of Adobe Systems Incorporated which may be registered in certain juris- dictions. 3 Contents • Copyright • How to use this book • Introduction • List of fables by title • Aesop’s Fables • Index of titles • Index of morals • How to create your own glossary and question pages • How to print and make your own book • Fable questions Click any line to jump to that section 4 How to use this book This book contains several sections. -

Makhai Fascicle 2 (Raw) “P & P”

MAKHAI FASCICLE 2 (RAW) This is only an incomplete fraction of MAKHAI. MAKHAI’s release is planned as 5 fascicles, each going through the stages of raw, rough and ready. “P & P” This fascicle is RAW. Misspellings abound. Chapters may be incomplete, to be finished or abandoned. Lines shoot into margins, and text turns to notes which turn to gibberish. There are no illustrations. February 20th, 2015 Contents Contents 2 II PROIOXIS & PALIOXIS: back and forth 7 55 The adventures of zen master Goto 11 56 Death questions 15 56.1 The original questions . 15 56.2 Budgie did a go-go: a pet urnery . 19 56.3 The final blasphemies . 24 57 Soul questions 29 58 Cat porn questions 35 59 Aesop: The Cat and the Gods 41 60 Aesop: The Dog and the Pond 43 61 Aesop: The Cat and the Mice 45 62 Aesop: The Dog and the Pond II 47 63 Aesop: The Goose and the Eggs 49 2 CONTENTS 64 Aesop: The Tortoise and the Hare 51 65 Aesop: The Boy Who Cried Wolf 53 66 Aesop: The Frog and the Ox 57 67 Aesop: The King of the Frogs 59 68 Aesop: The Deer Without A Heart 63 69 Aesop: The Miser and His Gold 67 70 Aesop: The Pious Woodman 69 71 Aesop: The Bird in Borrowed Feathers 73 72 Aesop: The Farmer and the Viper 75 73 Aesop: The Revel 77 74 Aesop: Wolves, Sheep, Dogs 79 75 Aesop: The Turkey, the Duck and the Chicken 81 76 Aesop: The Cat and the Lid 83 77 Aesop: The Sick Raven 85 78 Short aesops 87 79 Grimm: Children Playing Slaughter 91 80 Grimm: The Fairy-Queen and the Woodman’s Children 93 81 Grimm: Snow White 95 82 Grimm: Little Red Hot 123 83 The Marriage of Nitokris 139 3 -

Aesop's Fables

AESOP’S FABLES Read by Anton Lesser JUNIOR CLASSICS CHILDREN’S FAVOURITES NA120712D 1 The Dog and the Shadow 1:25 2 The Cock and the Pearl 1:01 3 The Wolf and the Lamb 1:19 4 The Wolf and the Crane 1:36 5 The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse 1:46 6 The Fox and the Crow 1:35 7 The Lion and the Mouse 1:27 8 The Swallow and the Other Birds 1:32 9 The Mountains in Labour 1:14 10 The Hares and the Frogs 1:05 11 The Wolf and the Kid 0:52 12 The Woodman and the Serpent 1:05 13 The Fox and the Stork 1:30 14 The Fox and the Mask 0:35 15 The Jay and the Peacock 1:05 16 The Frog and the Ox 1:35 17 Androcles and the Lion 1:43 18 The Bat, the Birds, and the Beasts 1:50 19 The Hart and the Hunter 1:02 20 The Serpent and the File 0:36 21 The Man and the Wood 0:33 22 The Dog and the Wolf 1:33 23 The Belly and the Members 0:59 24 The Fox and the Grapes 1:11 25 The Horse, Hunter, and Stag 1:18 2 26 The Peacock and Juno 0:35 27 The Fox and the Lion 0:38 28 The Lion and the Statue 1:14 29 The Ant and the Grasshopper 1:17 30 The Tree and the Reed 1:27 31 The Fox and the Cat 1:19 32 The Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing 0:43 33 The Man and His Two Wives 1:31 34 The Nurse and the Wolf 1:11 35 The Tortoise and the Birds 0:59 36 The Two Crabs 0:40 37 The Ass in the Lion’s Skin 0:49 38 The Two Fellows and the Bear 1:21 39 The Two Pots 0:52 40 The Four Oxen and the Lion 0:50 41 The Fisher and the Little Fish 0:47 42 The Crow and the Pitcher 1:14 43 The Man and the Satyr 1:14 44 The Goose With the Golden Eggs 0:49 45 The Labourer and the Nightingale 1:49 46 The Fox, the -

Philosophy in the Classroom

Philosophy in the Classroom Ever had difficulty inspiring your children to consider and discuss philo- sophical concepts? Philosophy in the Classroom helps teachers tap in to children’s natural wonder and curiosity. The practical lesson plans, built around Aesop’s fables, encourage children to formulate and express their own points of view, enabl- ing you to lead rich and rewarding philosophical discussions in the primary classroom. This highly practical and engaging classroom companion: • Prompts students to consider serious moral issues in an imaginative and stimulating way. • Uses Aesop’s fables as a springboard to pose challenging questions about the issues raised. • Provides 15 key themes including happiness, wisdom, self-reliance and judging others as the basis for classroom discussion. • Uses powerful and creative drawings to illustrate activities and photocopiable resources. Philosophy in the Classroom is an invaluable resource for any primary school teacher wanting to engage their students in meaningful philosophical reflection and discussion. Ron Shaw has many years of classroom experience and is the author of more than 40 books helping primary and secondary school students to improve their thinking skills. Philosophy in the Classroom Improving your pupils’ thinking skills and motivating them to learn Ron Shaw First published 2003 by Curriculum Corporation, Australia This edition published 2008 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2007. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © 2008 Ron Shaw All rights reserved. -

Artists in the Schools Directory 2018-2019

Artists in the Schools Directory 2018-2019 An Arts Education Program of About ahha Tulsa The mission of ahha Tulsa is to cultivate a more creative Tulsa through advocacy, education, and innovate partnerships, which contribute to the quality of life and economic vitality of the greater community. About Artists in the Schools The Artists in the Schools (AIS) program serves to provide students with high-quality experiences in the arts that inspire their creativity and confidence, further their academic learning, and foster their life-long appreciation of and participation in the arts. It also serves to provide teachers with new ideas for teaching and integrating the arts throughout the core academic subjects while also fostering their appreciation for how the arts can enrich their classrooms and the lives of their students. Through AIS, ahha Tulsa provides professional Teaching and Performing Artists in visual, performing, and literary arts to schools for enriching educational experiences. These Teaching and Performing Artists are professionals within their artistic discipline and have been selected through a rigorous application process by a panel of professional artists, educators, and invested community members. Not only do the experiences provided by the Teaching and Performing Artists raise students’ awareness of the role of the arts and professional artists in the community, participating students will cultivate the skills needed to succeed not just in the classroom but throughout life. These valuable skills include creativity, imagination, critical thinking, communication, and collaboration. AIS participants will: • Gain knowledge of contemporary art, contemporary artists, and contemporary art making practices. • Understand the historical and cultural contexts of works of art. -

The Fables of Aesop

y First published in 1894 First schocken edition published in 1966 Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 66-24908 ISBN 0-8052-0138-6 (paperback) l o Manufactured in the United States of America rof hild B98765432 P . F.J .C OF HARVARD PREFACE T is difficult to say what are and what are not the Fables of Æsop. Almost all the , fables that have appeared in the Western world have been sheltered at one time or another under the shadow of that name. I could at any rate enumerate at least seven hundred which have appeared in English in various books entitled Æsop's Fables. L’Estrange’s collection alone contains over five hundred. In the struggle for existence among all these a certain number stand out as being the most effective and the most familiar. I have attempted to bring most of these into the following pages. PAGE A Short History of the Æsopic Fable XV List of Fables . xxiii Æsop’s Fables . i Notes . • J99 Index of Fables . 225 6 ■ -j <5)@(--------------------- LIST OF FABLES PAGE 1. The Cock and the Pearl . 2 2. The Wolf and the Lamb . 4 3. The Dog and the Shadow . 7 4. The Lion’s Share . 8 5. The Wolf and the Crane . 1 0 6. The Man and the Serpent . 1 2 7. The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse . 1 5 8. The Fox and the Crow . -

The Ugly Duckling & the Tortoise and the Hare

THE UGLY DUCKLING & THE TORTOISE AND THE HARE Applause Series CURRICULUM GUIDE February 28 - March 1, 2013 GUIDE CONTENTS About Des Moines Performing Arts Page 3 Going to the Theater and Dear Teachers, Theater Etiquette Page 4 Thank you for joining us for the Applause Series presentation of The Ugly Duckling and The Tortoise and the Hare. These two Civic Center Field Trip classic tales — with timeless messages about the power of Information for Teachers perseverance and the truth that beauty is more than skin deep — Page 5 are told anew in this dazzling production. Without using any spoken word, Lightwire Theater brings the stories to life through Vocabulary movement, music, and remarkable electroluminescent puppets. Page 6 The result is an experience that both delights and moves children and adults alike. About the Performance Page 7 We thank you for sharing this special experience with your students and About Lightwire Theater hope that this study guide helps you Page 8 connect the performance to your in-classroom curriculum in ways that The Elements: you find valuable. In the following About the Movement pages, you will find contextual Page 9 information about the performance and related subjects, as well as a variety of The Elements: discussion questions and activities. About the Puppets Some pages are appropriate to Page 10 reproduce for your students; others are designed more specifically with you, The hare in The Tortoise and The Elements: their teacher, in mind. As such, we the Hare. About the Technology hope that you are able to “pick and Page 11 choose” material and ideas from the study guide to meet your class’s unique needs. -

Aesop's Fables

Aesop’s Fables This eBook is designed and published by Planet PDF. For more free eBooks visit our Web site at http://www.planetpdf.com Aesop’s Fables The Cock and the Pearl A cock was once strutting up and down the farmyard among the hens when suddenly he espied something shinning amid the straw. ‘Ho! ho!’ quoth he, ‘that’s for me,’ and soon rooted it out from beneath the straw. What did it turn out to be but a Pearl that by some chance had been lost in the yard? ‘You may be a treasure,’ quoth Master Cock, ‘to men that prize you, but for me I would rather have a single barley-corn than a peck of pearls.’ Precious things are for those that can prize them. 2 of 93 Aesop’s Fables The Wolf and the Lamb Once upon a time a Wolf was lapping at a spring on a hillside, when, looking up, what should he see but a Lamb just beginning to drink a little lower down. ‘There’s my supper,’ thought he, ‘if only I can find some excuse to seize it.’ Then he called out to the Lamb, ‘How dare you muddle the water from which I am drinking?’ ‘Nay, master, nay,’ said Lambikin; ‘if the water be muddy up there, I cannot be the cause of it, for it runs down from you to me.’ ‘Well, then,’ said the Wolf, ‘why did you call me bad names this time last year?’ ‘That cannot be,’ said the Lamb; ‘I am only six months old.’ ‘I don’t care,’ snarled the Wolf; ‘if it was not you it was your father;’ and with that he rushed upon the poor little Lamb and .WARRA WARRA WARRA WARRA WARRA .ate her all up. -

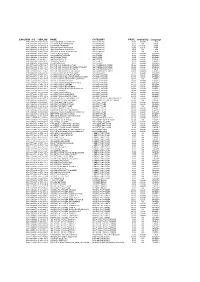

Tinytot Price List Updated

EAN (ISBN - 13) ISBN_NO NAME CATEGORY PRICE Availability Language 9788130406268 81-304-0626-8 100 CHANDMAMA KI KAHANIYAN 100 KAHANIYAN 90.00 Available HINDI 9788130406770 81-304-0677-2 100 DADA-DADI KI KAHANIYAN 100 KAHANIYAN 90.00 N/A HINDI 9788130406251 81-304-0625-X 100 NAITTIK KAHANIYAN 100 KAHANIYAN 90.00 Available HINDI 9788130406442 81-304-0644-6 100 NANA-NANI KI KAHANIYAN 100 KAHANIYAN 90.00 Available HINDI 9788130406428 81-304-0642-X 100 SHIKSHAPRAD KAHANIYAN 100 KAHANIYAN 90.00 N/A HINDI 9788130406435 81-304-0643-8 100 SOOJH BHOOJH KI KAHANIYAN 100 KAHANIYAN 90.00 N/A HINDI 9788130406381 81-304-0638-1 100 BEDTIMES STORIES 100 STORIES 90.00 Available ENGLISH 9788130406022 81-304-0602-0 100 GOODNIGHT STORIES 100 STORIES 90.00 Available ENGLISH 9788130406404 81-304-0640-3 100 GRANDMA TALES 100 STORIES 90.00 Available ENGLISH 9788130406411 81-304-0641-1 100 GRANDPA TALES 100 STORIES 90.00 Available ENGLISH 9788130406015 81-304-0601-2 100 MORAL STORIES 100 STORIES 90.00 Available ENGLISH 9788130406398 81-304-0639-X 100 WISDOM TALES 100 STORIES 90.00 Available ENGLISH 9788175731905 81-7573-190-7 TINY TOT 1001 WORDS IN ACTION 1001 WORDS IN PICTURES 150.00 Available ENGLISH 9788175731912 81-7573-191-5 TINY TOT 1001 WORDS IN PICTURE DICTIONARY 1001 WORDS IN PICTURES 150.00 Available ENGLISH 9788175731899 81-7573-189-3 TINY TOT 1001 WORDS IN PICTURES 1001 WORDS IN PICTURES 150.00 Available ENGLISH 9788175731929 81-7573-192-3 TINY TOT 1001 WORDS TO TALK ABOUT 1001 WORDS IN PICTURES 150.00 Available ENGLISH 9788130400198 81-304-0019-7 101