Staging the Nation | Ibraaz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobilities of Architecture in the Global Cold War: from Socialist Poland to Kuwait and Back

IJIA 4 (2) pp. 365–398 Intellect Limited 2015 International Journal of Islamic Architecture Volume 4 Number 2 © 2015 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/ijia.4.2.365_1 ŁUKASZ STANEK University of Manchester Mobilities of Architecture in the Global Cold War: From Socialist Poland to Kuwait and Back Abstract Keywords This article discusses the contribution of professionals from socialist countries to Gulf architecture architecture and urban planning in Kuwait in the final two decades of the Cold War. socialist Poland In so doing, it historicizes the accelerating circulation of labour, building materials, architectural discourses, images, and affects facilitated by world-wide, regional and local networks. globalization By focusing on a group of Polish architects, this article shows how their work in postmodernism Kuwait in the 1970s and 1980s responded to the disenchantment with architecture knowledge transfer and urbanization processes of the preceding two decades, felt as much in the Gulf as architectural labour in socialist Poland. In Kuwait, this disenchantment was expressed by a turn towards images, ways of use, and patterns of movement referring to ‘traditional’ urbanism, reinforced by Western debates in postmodernism and often at odds with the social realities of Kuwaiti urbanization. Rather than considering this shift as an architec- tural ‘mediation’ between (global) technology and (local) culture, this article shows how it was facilitated by re-contextualized expert systems, such as construction tech- nologies or Computer Aided Design software (CAD), and also by the specific portable ‘profile’ of experts from socialist countries. By showing the multilateral knowledge flows of the period between Eastern Europe and the Gulf, this article challenges diffusionist notions of architecture’s globalization as ‘Westernization’ and reconcep- tualizes the genealogy of architectural practices as these became world-wide. -

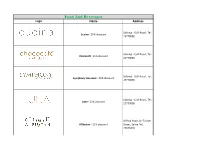

Food and Beverages Logo Name Address

Food And Beverages Logo Name Address Salmiya - Gulf Road , Tel: Cucina - 25% discount 25770000 Salmiya - Gulf Road , Tel: Chococafe- 25% discount 25770000 Salmiya - Gulf Road , Tel: Symphony Gourmet - 25% discount 25770000 Salmiya - Gulf Road , Tel: Luna - 25% discount 25770000 Al Bida Road, Al -Ta'awn Al Bustan - 25% discount Street, Salwa Tel: 25673410 Al Bida Road, Al -Ta'awn Eedam - 25% discount on homemade items only Street, Salwa Tel: 25673420 Al Bida Road, Al -Ta'awn Al Boom - 25% discount Street, Salwa Tel: 25673430 Al Bida Road, Al -Ta'awn Peacock - 25% discount during lunch only Street, Salwa Tel: 25673440 Marina mall / liwan/ the Nestle Toll House café - 15% discount village / Levels Tel : 22493773 Sharq, Al Hamra luxury Sushi bar - 12% discount center, 1st floor Sharq, Al Hamra luxury Versus Varsace Café - 12% discount center, 1st floor The Village, Kipco Tower Upper Crust - 10% discount Sharq Tel : 1821872 Murooj Sabhan Tel : Crumbs - 10% discount 22050270 Dar Al Awadhi, Kuwait Munch - 10% discount City Tel : 22322747 Gulf Road, Across from Mais Al Ghanim - 10% discount Kuwait Towers, Spoons Complex Tel: 22250655 Bneid Al gar - Al bastaki Mawal Lebnan Café & Restaurant - 15% discount hotel - 14th floor Tel : 22575169 Miral complex Tel : Debs Al reman - 15% Discount 22493773 Avenues Mall Tel : Boccini Pizzeria - 15% discount 22493773 Salmiya, Salem Mubarak ibis Hotel Restaurants- 20% discount Street and Sharq Tel : 25713872 Salmiya, Tel: 25742090- Dag Ayoush- 15% discount 55407179 Salmiya salem almubarak street - Basbakan- -

OPEC Bulletin

the OPEC MOMRDownload App free of charge! • Essential information on the oil market • 100+ interactive articles and tables detailing crude price movements, oil futures, prices and much more • Analysis of the world economy, world oil supply and demand • Compare data interactively and maximize information extraction OPEC Monthly Oil Market Report 12 June 2018 Feature article: World oil market prospects for the second half of 2018 Oil market highlights i Feature article iii Crude oil price movements 1 Commodity markets 9 World economy 12 World oil demand 32 World oil supply 44 Product markets and refinery operations 61 Tanker market 67 Oil trade 72 Stock movements 79 Balance of supply and demand 86 Two watershed years This month’s special edition of the OPEC Bulletin has been between June 2014 and January 2016, paralyzing the industry devoted to commemorating the 2nd anniversary of the landmark with frozen and cancelled projects, hundreds of thousands of ‘Declaration of Cooperation’ (DOC). A little over one year ago, lost jobs and drastic drops in investment. The mood pervading in the November 2017 issue of this publication, we marked the the industry was at an all-time low. overwhelming success of the DOC’s first year with a special When the news of this unprecedented OPEC-non-OPEC issue entitled ‘Forging history.’ cooperation was first announced at the end of 2016, it was Commentary And indeed, at that key juncture, one year into the DOC, initially greeted with a chorus of naysayers who claimed that history had already been made on several fronts — it was a year the Declaration’s goals of rebalancing the global oil market of ‘firsts’: the first production adjustment since Oran 2008; could never be achieved. -

Downloads/2003 Essay.Pdf, Accessed November 2012

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Nation Building in Kuwait 1961–1991 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/91b0909n Author Alomaim, Anas Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Nation Building in Kuwait 1961–1991 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture by Anas Alomaim 2016 © Copyright by Anas Alomaim 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Nation Building in Kuwait 1961–1991 by Anas Alomaim Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Sylvia Lavin, Chair Kuwait started the process of its nation building just few years prior to signing the independence agreement from the British mandate in 1961. Establishing Kuwait’s as modern, democratic, and independent nation, paradoxically, depended on a network of international organizations, foreign consultants, and world-renowned architects to build a series of architectural projects with a hybrid of local and foreign forms and functions to produce a convincing image of Kuwait national autonomy. Kuwait nationalism relied on architecture’s ability, as an art medium, to produce a seamless image of Kuwait as a modern country and led to citing it as one of the most democratic states in the Middle East. The construction of all major projects of Kuwait’s nation building followed a similar path; for example, all mashare’e kubra [major projects] of the state that started early 1960s included particular geometries, monumental forms, and symbolic elements inspired by the vernacular life of Kuwait to establish its legitimacy. -

Company Profile

AL KULAIB Universal CO. for System & Equipments A KFD Grade “A” Approved Company in Firefighting and Fire Alarm Systems COMPANY PROFILE 1 P.O. Box 240 Safat, Code 13003 Kuwait ISO 9001:2015 Email: [email protected] ISO 14001:2015www.akuco.com Tel: 24921734 / 5 / 6, Fax: 24915256 BS OHSAS 18001:2007 CONTENTS ABOUT US 3 OUR MISSION, VISION, & VALUES 4 COMPANY DEPARTMENTS 5 REGISTRATION & APPROVALS 6 -8 PRODUCT RANGE 9 PROJECT REFERENCES 33 2 ISO 9001:2015 ISO 14001:2015www.akuco.com BS OHSAS 18001:2007 ABOUT US • Al Kulaib Safety & Security Co. is established since 1972 under ASAK group of Companies. • ISO certified company dedicated to provide the highest quality of health, safety, and security solutions. • KFD Approved Grade “A” Company • The Company has its own fire extinguisher workshop and Showroom. • One of the 3 Companies in MEW List of Approved Supplier and Contractor for Fire Fighting and Fire Alarm Systems. • Today it is representing world renowned brands with the highest quality standard from Germany, Switzerland, USA, UK, among others. 3 ISO 9001:2015 ISO 14001:2015www.akuco.com BS OHSAS 18001:2007 OUR MISSION, VISION, & VALUES As a team of highly trained and dedicated professionals, it is our mission to provide the highest standard of service in all aspects of Fire Protection Systems. We are a service provider and we stand ready to provide fire suppression, fire prevention and safety. We will faithfully provide these vital services, promptly and safely. We will strive to be a model of excellence in providing fire protection, safety measures, and be an organization dedicated to continuous improvement, innovation, creativity and accountability. -

Mps Adasani, Kandari and Quwaiaan Resign Continued from Page 1 Adasani Against the Prime Minister

SUBSCRIPTION THURSDAY, MAY 1, 2014 RAJAB 2, 1435 AH www.kuwaittimes.net MPs Adasani, Kandari Max 38º Min 24º and Quwaiaan resign High Tide 01:40 & 12:37 Low Tide Hashem too mulls quitting after PM grilling scrapped 07:14 & 20:01 40 PAGES NO: 16152 150 FILS KUWAIT: In a dramatic and rare move, MPs Abdulkarim conspiracy theories Al-Kandari, Riyadh Al-Adasani and Hussein Quwaiaan yesterday announced they were quitting their parlia- mentary seats in protest at the National Assembly’s rejection of their grilling against the prime minister. Please do! During yesterday’s session, Kandari said he has decided to resign from the Assembly in order to safeguard the constitution and to protest against the “unconstitution- al” action of rejecting a grilling against the prime minis- ter. Adasani made a similar announcement and both By Badrya Darwish immediately left the chamber. Later, Quwaiaan announced on his Twitter account that he has decided to resign too in protest against “breaching the constitu- tion”. The surprising move came one day after the Assembly comfortably approved a government request [email protected] to reject a grilling against Prime Minister HH Sheikh Jaber Al-Mubarak Al-Sabah, which was demanded by the three resigning MPs. he circus season started yesterday in Kuwait Speaker Marzouk Al-Ghanem told the lawmakers under the Abdullah Salem dome where the that he will deal with the resignations in accordance Tperformance was held. It was an intriguing with the internal charter of the Assembly. According to performance by our players - the honorable gentle- the law, MPs must submit their resignations in writing men of parliament. -

Domestic Workers' Legal Guide

ENGLISH Kuwait’s National Awareness Campaign on the Rights of Domestic Workers’ Domestic Workers and Employers Legal Guide Organized By In Partnership With Table of Contents Assault 26 Shelter 41 Sexual Assault 28 Types of Residency 42 Financial Matters 4 Advice on Residency Law 32 Numbers & Places of Interest 43 Living Conditions 8 Legal Advice 33 Embassies & Consulates in Kuwait 44 Location & Nature of Work 12 Legal Procedures 34 Embassies & Consulates Outside Kuwait 48 Working Hours & Holidays 16 Guarantees for Suspect 35 Investigation Departments 50 General Labour Rights 18 Deportation & Absconding 36 Public Prosecution 51 Duties of Domestic Workers 20 Remand 37 Police Stations 52 General Rights 21 Criminal Complaints 38 E-services 62 Kidnap & False Imprisonment 22 Labour Complaint 40 Laws 63 About One Roof Campaign “One Roof” is a campaign that aims to raise awareness about domestic workers’ rights. This campaign is a partnership between the Human Line Organization and the Social Work Society in collaboration with the Ministry of Interior and other international organizations. “One Roof” Campaign works toward building a positive relationship between the employer and domestic worker that is governed by justice and serves to protect the rights and dignity of both parties. The campaign aims to raise awareness about domestic workers’ rights as stated in Kuwaiti laws to reduce conflict and problems that may arise due to the lack of awareness of laws that regulate the work of domestic workers in Kuwait. “One Roof” also seeks to emphasize that domestic work is an occupation that should be regulated by laws and procedures. About the Legal Guide While the relationship between the employer and domestic worker in Kuwait is successful and effective in most cases, it is still important for domestic workers to be knowledgeable of their legal rights and responsibilities in order to be familiar with the rules that regulate their work and be able to demand their rights in case they were violated. -

NEW ARAB URBANISM the Challenge to Sustainability and Culture in the Gulf

Harvard Kennedy School Middle East Initiative NEW ARAB URBANISM The Challenge to Sustainability and Culture in the Gulf Professor Steven Caton, Principal Investigator Professor of Contemporary Arab Studies Department of Anthropology And Nader Ardalan, Project Director Center for Middle East Studies Harvard University FINAL REPORT Prepared for The Kuwait Program Research Fund John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University December 2, 2010 NEW ARAB URBANISM The Challenge of Sustainability & Culture in the Gulf Table of Contents Preface Ch. 1 Introduction Part One – Interpretive Essays Ch. 2 Kuwait Ch. 3 Qatar Ch. 4 UAE Part Two – Case Studies Ch. 5 Kuwait Ch. 6 Qatar Ch. 7 UAE Ch. 8 Epilogue Appendices Sustainable Guidelines & Assessment Criteria Focus Group Agendas, Participants and Questions Bibliography 2 Preface This draft of the final report is in fulfillment of a fieldwork project, conducted from January to February, 2010, and sponsored by the Harvard Kennedy School Middle East Initiative, funded by the Kuwait Foundation for Arts and Sciences. We are enormously grateful to our focus-group facilitators and participants in the three countries of the region we visited and to the generosity with which our friends, old and new, welcomed us into their homes and shared with us their deep insights into the challenges facing the region with respect to environmental sustainability and cultural identity, the primary foci of our research. This report contains information that hopefully will be of use to the peoples of the region but also to peoples elsewhere in the world grappling with urban development and sustainability. We also thank our peer-review group for taking the time to read the report and to communicate to us their comments and criticisms. -

Kuwait's Moment of Truth

arab uprisings Kuwait’s Moment of Truth November 1, 2012 YASSER AL-ZAYYAT/AFP/GETTY IMAGES AL-ZAYYAT/AFP/GETTY YASSER POMEPS Briefings 15 Contents Kuwait’s balancing act . 5 Kuwait’s short 19th century . 7 Why reform in the Gulf monarchies is a family feud . 10 Kuwait: too much politics, or not enough? . 11 Ahistorical Kuwaiti sectarianism . 13 Kuwait’s impatient youth movement . 16 Jailed for tweeting in Kuwait . 18 Kuwait’s constitution showdown . 19 The identity politics of Kuwait’s election . 22 Political showdown in Kuwait . 25 The Project on Middle East Political Science The Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS) is a collaborative network which aims to increase the impact of political scientists specializing in the study of the Middle East in the public sphere and in the academic community . POMEPS, directed by Marc Lynch, is based at the Institute for Middle East Studies at the George Washington University and is supported by the Carnegie Corporation and the Social Science Research Council . It is a co-sponsor of the Middle East Channel (http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com) . For more information, see http://www .pomeps .org . Online Article Index Kuwait’s balancing act http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2012/10/23/kuwait_s_balancing_act Kuwait’s short 19th century http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2011/12/15/kuwaits_short_19th_century Why reform in the Gulf monarchies is a family feud http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2011/03/04/why_reform_in_the_gulf_monarchies_is_a_family_feud Kuwait: too much -

Exploring the Global Petroleumscape

9 PRECIOUS PROPERTY Water and Oil in Twentieth-Century Kuwait Laura Hindelang In early 1962, Kuwait’s first substantial subterranean water reservoir was discovered at Raudhatain in northern Kuwait.1 The Ralph M. Parsons company, which was conducting hydrogeological surveys on behalf of the government of Kuwait, was a US firm formerly active in building oil refineries. Geologists described how “the fresh water [had] gathered in a geological basin one side of which is an anticline of the structure forming the Raudhatain oil-field.”2 Raudhatain’s water (most of it fossil) and petroleum effectively sprang from the same geological formation and were accessed by similar technologies. This multifaceted historical relationship between Kuwait’s water(scape) and petroleumscape, with its spatial and architectural, social, and political as well as symbolic and representational layers, is the topic of this chapter. One can trace petroleum’s impact on twentieth-century Kuwait in many ways: airplane and automobile culture, gas stations, air-conditioning, and the proliferation of plastics—all depend on petroleum. In Kuwait, the oil industry but also the oil revenue-financed govern- ment transformed the city-state’s urban and desert landscapes, its architectural forms, and the built environment. However, despite the growing omnipresence of petroleum-derived products and lifestyles, petroleum as a raw material, as an unprocessed liquid, has usually remained invisible in urban space. Chemically, oil and water do not mix, but in Kuwait, as the brief example of Raudhatain illustrates, the history of oil and the history of water flow together. Yet, the visual-spatial absence of oil has obscured the two fluids’ interdependent conditions of existence. -

Building for Oil: Corporate Colonialism, Nationalism and Urban Modernity in Ahmadi, 1946-1992

Building for Oil: Corporate Colonialism, Nationalism and Urban Modernity in Ahmadi, 1946-1992 By Reem IR Alissa A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Professor Grieg Crysler Professor Teresa Caldeira Fall 2012 Abstract Building for Oil: Corporate Colonialism, Nationalism and Urban Modernity in Ahmadi, 1946-1992 By Reem IR Alissa Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Located at the intersection of oil and space, this dissertation highlights the role of oil as an agent of political, social and cultural change at the level of the everyday urban experience by introducing the oil company town as a modern architectural and urban planning prototype that has been largely neglected in the Middle East. Using the Kuwait Oil Company (KOC) town of Ahmadi as a case in point this article offers a new history of oil, architecture and urbanism in Kuwait since 1946. Apart from oil dictating Ahmadi’s location and reason for being various actors were complicit in the creation and playing out of Ahmadi’s urban modernity: British KOC officials, the company’s architectural firm Wilson Mason & Partners, nationalism, the process of Kuwaitization, Ahmadi’s architecture and urbanism, and, especially, the town’s residents. I argue that Ahmadi’s colonial modernity which was initially targeted at the expatriate employees of the company during the 1950s, was later adopted by KOC’s Kuwaiti employees after the country’s independence in 1961, and in turn mediated a drastically new lifestyle, or urban modernity, during the 1960s and 1970s. -

GRAND HYATT KUWAIT 6Th Ring Road, South Surra, Al Zahra 47451, Kuwait T +965 2221 1234 Grandhyattkuwait.Com

GRAND HYATT KUWAIT 6th Ring Road, South Surra, Al Zahra 47451, Kuwait T +965 2221 1234 grandhyattkuwait.com ACCOMMODATIONS RESTAURANTS & LOUNGE 302 elegantly designed guestrooms and suites ranging between • ’Stambul — An expansive lifestyle experience celebrating the 45 sqm and 260 sqm with captivating skyline views. The famed influences of Turkish cuisine delivered spontaneously and impressive accommodation offering features 21 guestrooms and theatrically. suites with private landscaped garden terraces, 35 Grand Club Suites, 8 Junior Suites and one Presidential Suite. • Liberté — A modern French brasserie rooted in classicism, but reimagined through innovation. The food is ingeniously brought to life Grand Club — A private social space where our most through culinary creativity and delivered through a sense of fresh and distinguished guests can enjoy daily breakfast, light energetic feminine energy. refreshments throughout the day and fine evening canapés. • MEI LI — Authentic Chinese cuisine inspired by the most popular dishes served at the Imperial Palaces of old Beijing. The food All Accommodations Offer provides the narrative for faithfully crafted classic dishes, which • Rooms with unobstructed skyline views includes the world renowned Peking Duck and Beggar’s Chicken. • Functional walk-in closet with generous garment hanging space • Saheel Lounge — Distinctive lobby lounge ideal for socializing in a casual yet refined setting. A tone setting experience enriched with • One-touch room adjustment features for temperature, lighting and breathtaking works of art. guest comfort • Ultra High Definition TV’s with browser technology • Luxurious rain shower and contemporary freestanding bathtub MEETING & EVENT FACILITIES • Exclusively commissioned artwork • Grand Ballroom — A striking multipurpose events venue ideal for weddings, conferences, exhibitions, grand galas and cocktail • Nespresso coffee machines in Grand Club Rooms and Suites receptions.