OPEC Bulletin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobilities of Architecture in the Global Cold War: from Socialist Poland to Kuwait and Back

IJIA 4 (2) pp. 365–398 Intellect Limited 2015 International Journal of Islamic Architecture Volume 4 Number 2 © 2015 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/ijia.4.2.365_1 ŁUKASZ STANEK University of Manchester Mobilities of Architecture in the Global Cold War: From Socialist Poland to Kuwait and Back Abstract Keywords This article discusses the contribution of professionals from socialist countries to Gulf architecture architecture and urban planning in Kuwait in the final two decades of the Cold War. socialist Poland In so doing, it historicizes the accelerating circulation of labour, building materials, architectural discourses, images, and affects facilitated by world-wide, regional and local networks. globalization By focusing on a group of Polish architects, this article shows how their work in postmodernism Kuwait in the 1970s and 1980s responded to the disenchantment with architecture knowledge transfer and urbanization processes of the preceding two decades, felt as much in the Gulf as architectural labour in socialist Poland. In Kuwait, this disenchantment was expressed by a turn towards images, ways of use, and patterns of movement referring to ‘traditional’ urbanism, reinforced by Western debates in postmodernism and often at odds with the social realities of Kuwaiti urbanization. Rather than considering this shift as an architec- tural ‘mediation’ between (global) technology and (local) culture, this article shows how it was facilitated by re-contextualized expert systems, such as construction tech- nologies or Computer Aided Design software (CAD), and also by the specific portable ‘profile’ of experts from socialist countries. By showing the multilateral knowledge flows of the period between Eastern Europe and the Gulf, this article challenges diffusionist notions of architecture’s globalization as ‘Westernization’ and reconcep- tualizes the genealogy of architectural practices as these became world-wide. -

Candidate Resume

Flat No-a/303, Dharti Park, Behind Shriniwas , Palghar Thane MH 401501 India P : +91 9321883949 E : [email protected] W : www.hawkcl.com Hawk ID # 57610 Maintenance / Engineer, Security P,r Management Residential Country : Kuwait Nationality : Egypt Resume Title : Architect Engineer Notice Period : 1 Days EDUCATION Qualification Institute / College /University Year Country Engineering EL-AZHAR University 2007 Egypt CAREER SUMMARY From Month/ To Month/ Position Employer Country Year Year PACKAGE Reputed Company Kuwait 03/2016 / MANAGER PROJECT Sabah Al Salem Kuwait 06/2013 03/2016 ENGINEER University ARCHITECT SAVINGS AND CREDIT Kuwait 03/2012 06/2013 ENGINEER BANK Princess NORAH SITE ENGINEER Saudi Arabia 03/2010 02/2012 University ARAB CONSULTING SITE ENGINEER Egypt 03/2008 03/2010 ENGINEER MOHARAM Design Engineer ETMAN Company Egypt 02/2007 03/2008 ADDITIONAL CERTIFICATE AND TECHNICAL QUALIFICATION Name Of The Course Course Date Valid Upto Name Of Organisation Current Salary Expected Salary (Monthly In USD): Not Mention (Monthly In USD): Not Mention Additional Skills : SKILLS Management , Leadership, Team Player, Creative, Time management, Results Oriented, C ommunication & Interpersonal effectiveness Information Seeking Fast learner especially with new technologies, Innovative. Computer Skills: AutoCAD D / Rivet (Beginner) / Microsoft Office / outlook / Internet. AWARDS RECEIVED • Safety award in Recognition of Exemplary Performance (Award by Tecnimont & SK Engineering & construction). • Safety award for Excellent safety performance and Compliance (Award by SAUDI BINLADIN GROUP & Kharafi National). EDUCATION & PROFESSIONAL Courses/Trainings • Bachelors Degree, Faculty of Architectural Engineering, EL-AZHAR University, Cairo, Egypt. () • Attended Site training with (Arab Contractor Engineering, Egypt). • Autodesk AutoCAD Architecture (Certification from YAT Education Center - Egypt). • Autodesk Revit Architecture (Certification from YAT Education Center - Egypt). -

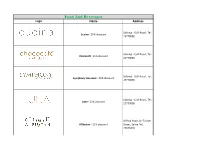

Food and Beverages Logo Name Address

Food And Beverages Logo Name Address Salmiya - Gulf Road , Tel: Cucina - 25% discount 25770000 Salmiya - Gulf Road , Tel: Chococafe- 25% discount 25770000 Salmiya - Gulf Road , Tel: Symphony Gourmet - 25% discount 25770000 Salmiya - Gulf Road , Tel: Luna - 25% discount 25770000 Al Bida Road, Al -Ta'awn Al Bustan - 25% discount Street, Salwa Tel: 25673410 Al Bida Road, Al -Ta'awn Eedam - 25% discount on homemade items only Street, Salwa Tel: 25673420 Al Bida Road, Al -Ta'awn Al Boom - 25% discount Street, Salwa Tel: 25673430 Al Bida Road, Al -Ta'awn Peacock - 25% discount during lunch only Street, Salwa Tel: 25673440 Marina mall / liwan/ the Nestle Toll House café - 15% discount village / Levels Tel : 22493773 Sharq, Al Hamra luxury Sushi bar - 12% discount center, 1st floor Sharq, Al Hamra luxury Versus Varsace Café - 12% discount center, 1st floor The Village, Kipco Tower Upper Crust - 10% discount Sharq Tel : 1821872 Murooj Sabhan Tel : Crumbs - 10% discount 22050270 Dar Al Awadhi, Kuwait Munch - 10% discount City Tel : 22322747 Gulf Road, Across from Mais Al Ghanim - 10% discount Kuwait Towers, Spoons Complex Tel: 22250655 Bneid Al gar - Al bastaki Mawal Lebnan Café & Restaurant - 15% discount hotel - 14th floor Tel : 22575169 Miral complex Tel : Debs Al reman - 15% Discount 22493773 Avenues Mall Tel : Boccini Pizzeria - 15% discount 22493773 Salmiya, Salem Mubarak ibis Hotel Restaurants- 20% discount Street and Sharq Tel : 25713872 Salmiya, Tel: 25742090- Dag Ayoush- 15% discount 55407179 Salmiya salem almubarak street - Basbakan- -

Downloads/2003 Essay.Pdf, Accessed November 2012

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Nation Building in Kuwait 1961–1991 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/91b0909n Author Alomaim, Anas Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Nation Building in Kuwait 1961–1991 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture by Anas Alomaim 2016 © Copyright by Anas Alomaim 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Nation Building in Kuwait 1961–1991 by Anas Alomaim Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Sylvia Lavin, Chair Kuwait started the process of its nation building just few years prior to signing the independence agreement from the British mandate in 1961. Establishing Kuwait’s as modern, democratic, and independent nation, paradoxically, depended on a network of international organizations, foreign consultants, and world-renowned architects to build a series of architectural projects with a hybrid of local and foreign forms and functions to produce a convincing image of Kuwait national autonomy. Kuwait nationalism relied on architecture’s ability, as an art medium, to produce a seamless image of Kuwait as a modern country and led to citing it as one of the most democratic states in the Middle East. The construction of all major projects of Kuwait’s nation building followed a similar path; for example, all mashare’e kubra [major projects] of the state that started early 1960s included particular geometries, monumental forms, and symbolic elements inspired by the vernacular life of Kuwait to establish its legitimacy. -

Company Profile

AL KULAIB Universal CO. for System & Equipments A KFD Grade “A” Approved Company in Firefighting and Fire Alarm Systems COMPANY PROFILE 1 P.O. Box 240 Safat, Code 13003 Kuwait ISO 9001:2015 Email: [email protected] ISO 14001:2015www.akuco.com Tel: 24921734 / 5 / 6, Fax: 24915256 BS OHSAS 18001:2007 CONTENTS ABOUT US 3 OUR MISSION, VISION, & VALUES 4 COMPANY DEPARTMENTS 5 REGISTRATION & APPROVALS 6 -8 PRODUCT RANGE 9 PROJECT REFERENCES 33 2 ISO 9001:2015 ISO 14001:2015www.akuco.com BS OHSAS 18001:2007 ABOUT US • Al Kulaib Safety & Security Co. is established since 1972 under ASAK group of Companies. • ISO certified company dedicated to provide the highest quality of health, safety, and security solutions. • KFD Approved Grade “A” Company • The Company has its own fire extinguisher workshop and Showroom. • One of the 3 Companies in MEW List of Approved Supplier and Contractor for Fire Fighting and Fire Alarm Systems. • Today it is representing world renowned brands with the highest quality standard from Germany, Switzerland, USA, UK, among others. 3 ISO 9001:2015 ISO 14001:2015www.akuco.com BS OHSAS 18001:2007 OUR MISSION, VISION, & VALUES As a team of highly trained and dedicated professionals, it is our mission to provide the highest standard of service in all aspects of Fire Protection Systems. We are a service provider and we stand ready to provide fire suppression, fire prevention and safety. We will faithfully provide these vital services, promptly and safely. We will strive to be a model of excellence in providing fire protection, safety measures, and be an organization dedicated to continuous improvement, innovation, creativity and accountability. -

Mps Adasani, Kandari and Quwaiaan Resign Continued from Page 1 Adasani Against the Prime Minister

SUBSCRIPTION THURSDAY, MAY 1, 2014 RAJAB 2, 1435 AH www.kuwaittimes.net MPs Adasani, Kandari Max 38º Min 24º and Quwaiaan resign High Tide 01:40 & 12:37 Low Tide Hashem too mulls quitting after PM grilling scrapped 07:14 & 20:01 40 PAGES NO: 16152 150 FILS KUWAIT: In a dramatic and rare move, MPs Abdulkarim conspiracy theories Al-Kandari, Riyadh Al-Adasani and Hussein Quwaiaan yesterday announced they were quitting their parlia- mentary seats in protest at the National Assembly’s rejection of their grilling against the prime minister. Please do! During yesterday’s session, Kandari said he has decided to resign from the Assembly in order to safeguard the constitution and to protest against the “unconstitution- al” action of rejecting a grilling against the prime minis- ter. Adasani made a similar announcement and both By Badrya Darwish immediately left the chamber. Later, Quwaiaan announced on his Twitter account that he has decided to resign too in protest against “breaching the constitu- tion”. The surprising move came one day after the Assembly comfortably approved a government request [email protected] to reject a grilling against Prime Minister HH Sheikh Jaber Al-Mubarak Al-Sabah, which was demanded by the three resigning MPs. he circus season started yesterday in Kuwait Speaker Marzouk Al-Ghanem told the lawmakers under the Abdullah Salem dome where the that he will deal with the resignations in accordance Tperformance was held. It was an intriguing with the internal charter of the Assembly. According to performance by our players - the honorable gentle- the law, MPs must submit their resignations in writing men of parliament. -

Domestic Workers' Legal Guide

ENGLISH Kuwait’s National Awareness Campaign on the Rights of Domestic Workers’ Domestic Workers and Employers Legal Guide Organized By In Partnership With Table of Contents Assault 26 Shelter 41 Sexual Assault 28 Types of Residency 42 Financial Matters 4 Advice on Residency Law 32 Numbers & Places of Interest 43 Living Conditions 8 Legal Advice 33 Embassies & Consulates in Kuwait 44 Location & Nature of Work 12 Legal Procedures 34 Embassies & Consulates Outside Kuwait 48 Working Hours & Holidays 16 Guarantees for Suspect 35 Investigation Departments 50 General Labour Rights 18 Deportation & Absconding 36 Public Prosecution 51 Duties of Domestic Workers 20 Remand 37 Police Stations 52 General Rights 21 Criminal Complaints 38 E-services 62 Kidnap & False Imprisonment 22 Labour Complaint 40 Laws 63 About One Roof Campaign “One Roof” is a campaign that aims to raise awareness about domestic workers’ rights. This campaign is a partnership between the Human Line Organization and the Social Work Society in collaboration with the Ministry of Interior and other international organizations. “One Roof” Campaign works toward building a positive relationship between the employer and domestic worker that is governed by justice and serves to protect the rights and dignity of both parties. The campaign aims to raise awareness about domestic workers’ rights as stated in Kuwaiti laws to reduce conflict and problems that may arise due to the lack of awareness of laws that regulate the work of domestic workers in Kuwait. “One Roof” also seeks to emphasize that domestic work is an occupation that should be regulated by laws and procedures. About the Legal Guide While the relationship between the employer and domestic worker in Kuwait is successful and effective in most cases, it is still important for domestic workers to be knowledgeable of their legal rights and responsibilities in order to be familiar with the rules that regulate their work and be able to demand their rights in case they were violated. -

Kuwait: Human Needs in the Environment of Human Settlements

5TATE OF I\UWAIT PL.ANNING BOARD HUMAN NEEDS IN THE ENVIRONMENT OF HUMAN SETTLEMENTS A Report submitted to the United Nations Conference on Human Settlements Vancouver, May 31-June 11, 1976 CANADA STATE Of KUulAIT l PLANfHNG BOARD ...� HUMAN NEEDS IN THE ENVIRONMENT Of HUMAN SETTLEMENTS A Report submitted to the United Nations Conference on Human Settlements Vancouver, �ay 31 - June 11, 1976 CAr-JADA I·· _. : CONTENTS Chapter Page Introduction I The Physical, Historical & Economic Background of Modern Kuwait 1 - 7 II The Immediate Improvement of the Quality of Life in Kuwait 8 - 19 III Formation of a National Policy Dealing With Regional Planning, Land Use, Mobilization and Allocation of Resources 20 - 36 IV \Jays and Means 37 - 48 ., "· I Foreword This is the national report which has been prepared for • the United Nations Conference on Human Settlements to be held in Vancouver 1976. The draft report of the same was submitted to the Regional Preparatory Conference on Human Settiements which was held in Tehran, Iran 1975. The proposed Projects for 1976-81 Five-Year Plan have been included, consisting of the aims and objectives of Develop ment for Health� Education, Agriculture, Industry, Electricity and water and.&raicl. Services Sectors. The statistics enclosed have been corrected and revised according to the latest figures available. The compilation of this report has been supervised by Miss Mariam Awadi, Head of the Human Settlement Division, Department of the Environment in the Planning Board, in collaboration with the following Government Ministries and Bodies: Ministry of Social Affairs & Labour Ministry of Education Ministry of Electricity & Water Ministry of Public Health Kuwait University Kuwait Municipality Introduction In assessing and analystQg .Kuwait Ls achievements bn the field of human settlements, one can easily perceive that the Government has been inspired by certain principles, objectives, policies and means, by way of its fulfilment. -

NEW ARAB URBANISM the Challenge to Sustainability and Culture in the Gulf

Harvard Kennedy School Middle East Initiative NEW ARAB URBANISM The Challenge to Sustainability and Culture in the Gulf Professor Steven Caton, Principal Investigator Professor of Contemporary Arab Studies Department of Anthropology And Nader Ardalan, Project Director Center for Middle East Studies Harvard University FINAL REPORT Prepared for The Kuwait Program Research Fund John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University December 2, 2010 NEW ARAB URBANISM The Challenge of Sustainability & Culture in the Gulf Table of Contents Preface Ch. 1 Introduction Part One – Interpretive Essays Ch. 2 Kuwait Ch. 3 Qatar Ch. 4 UAE Part Two – Case Studies Ch. 5 Kuwait Ch. 6 Qatar Ch. 7 UAE Ch. 8 Epilogue Appendices Sustainable Guidelines & Assessment Criteria Focus Group Agendas, Participants and Questions Bibliography 2 Preface This draft of the final report is in fulfillment of a fieldwork project, conducted from January to February, 2010, and sponsored by the Harvard Kennedy School Middle East Initiative, funded by the Kuwait Foundation for Arts and Sciences. We are enormously grateful to our focus-group facilitators and participants in the three countries of the region we visited and to the generosity with which our friends, old and new, welcomed us into their homes and shared with us their deep insights into the challenges facing the region with respect to environmental sustainability and cultural identity, the primary foci of our research. This report contains information that hopefully will be of use to the peoples of the region but also to peoples elsewhere in the world grappling with urban development and sustainability. We also thank our peer-review group for taking the time to read the report and to communicate to us their comments and criticisms. -

Kuwait's Moment of Truth

arab uprisings Kuwait’s Moment of Truth November 1, 2012 YASSER AL-ZAYYAT/AFP/GETTY IMAGES AL-ZAYYAT/AFP/GETTY YASSER POMEPS Briefings 15 Contents Kuwait’s balancing act . 5 Kuwait’s short 19th century . 7 Why reform in the Gulf monarchies is a family feud . 10 Kuwait: too much politics, or not enough? . 11 Ahistorical Kuwaiti sectarianism . 13 Kuwait’s impatient youth movement . 16 Jailed for tweeting in Kuwait . 18 Kuwait’s constitution showdown . 19 The identity politics of Kuwait’s election . 22 Political showdown in Kuwait . 25 The Project on Middle East Political Science The Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS) is a collaborative network which aims to increase the impact of political scientists specializing in the study of the Middle East in the public sphere and in the academic community . POMEPS, directed by Marc Lynch, is based at the Institute for Middle East Studies at the George Washington University and is supported by the Carnegie Corporation and the Social Science Research Council . It is a co-sponsor of the Middle East Channel (http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com) . For more information, see http://www .pomeps .org . Online Article Index Kuwait’s balancing act http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2012/10/23/kuwait_s_balancing_act Kuwait’s short 19th century http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2011/12/15/kuwaits_short_19th_century Why reform in the Gulf monarchies is a family feud http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2011/03/04/why_reform_in_the_gulf_monarchies_is_a_family_feud Kuwait: too much -

January 13, 2021

Wave 2 of Hat-trick hero QFTH to Bounedjah cover more fires Al Sadd sectors, says to win over official Al Duhail Business | 01 Sport | 11 WEDNESDAY 13 JANUARY 2021 29 JUMADA I - 1442 VOLUME 25 NUMBER 8501 www.thepeninsula.qa 2 RIYALS Build your own plan! Terms & Conditions Apply Amir receives MME signs contract to build container city phone call from SANAULLAH ATAULLAH PM of Greece THE PENINSULA QNA — DOHA To preserve the environment by providing safe alternative Amir H H Sheikh Tamim bin storage facility to individuals, Hamad Al Thani received entities, the Ministry of Munic- yesterday morning a telephone ipality and Environment (MME) call from Prime Minister of the yesterday signed a contract with Hellenic Republic H E Kyriakos Continental Trading Company Mitsotakis, during which he to build and operate a self congratulated H H the Amir on storage container-city in Bojoud the Gulf reconciliation and the area on Al Majd Road opposite positive outcomes of the 41st Birkat Al Awamer. session of the Supreme Council The main purpose of the of the Gulf Cooperation Council project is to provide alternative (GCC). storage facility to citizens and During the telephone call, expatriates to curb the practice they reviewed the bilateral rela- Minister of Municipality and Environment, H E Abdullah bin Abdulaziz of at random stockpile of their tions between the two countries bin Turki Al Subaie, with officials from the Ministry and Continental belongings in residential areas, The main purpose of the project, expected to and means to enhance them in farms and public places that will come into operation within four months, is to Trading Co (CTC), after signing the contract between the ministry various domains. -

Exploring the Global Petroleumscape

9 PRECIOUS PROPERTY Water and Oil in Twentieth-Century Kuwait Laura Hindelang In early 1962, Kuwait’s first substantial subterranean water reservoir was discovered at Raudhatain in northern Kuwait.1 The Ralph M. Parsons company, which was conducting hydrogeological surveys on behalf of the government of Kuwait, was a US firm formerly active in building oil refineries. Geologists described how “the fresh water [had] gathered in a geological basin one side of which is an anticline of the structure forming the Raudhatain oil-field.”2 Raudhatain’s water (most of it fossil) and petroleum effectively sprang from the same geological formation and were accessed by similar technologies. This multifaceted historical relationship between Kuwait’s water(scape) and petroleumscape, with its spatial and architectural, social, and political as well as symbolic and representational layers, is the topic of this chapter. One can trace petroleum’s impact on twentieth-century Kuwait in many ways: airplane and automobile culture, gas stations, air-conditioning, and the proliferation of plastics—all depend on petroleum. In Kuwait, the oil industry but also the oil revenue-financed govern- ment transformed the city-state’s urban and desert landscapes, its architectural forms, and the built environment. However, despite the growing omnipresence of petroleum-derived products and lifestyles, petroleum as a raw material, as an unprocessed liquid, has usually remained invisible in urban space. Chemically, oil and water do not mix, but in Kuwait, as the brief example of Raudhatain illustrates, the history of oil and the history of water flow together. Yet, the visual-spatial absence of oil has obscured the two fluids’ interdependent conditions of existence.