Air Quality and Coronavirus: a Glimpse of a Different Future Or Business As Usual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cardiff Meetings & Conferences Guide

CARDIFF MEETINGS & CONFERENCES GUIDE www.meetincardiff.com WELCOME TO CARDIFF CONTENTS AN ATTRACTIVE CITY, A GREAT VENUE 02 Welcome to Cardiff That’s Cardiff – a city on the move We’ll help you find the right venue and 04 Essential Cardiff and rapidly becoming one of the UK’s we’ll take the hassle out of booking 08 Cardiff - a Top Convention City top destinations for conventions, hotels – all free of charge. All you need Meet in Cardiff conferences, business meetings. The to do is call or email us and one of our 11 city’s success has been recognised by conference organisers will get things 14 Make Your Event Different the British Meetings and Events Industry moving for you. Meanwhile, this guide 16 The Cardiff Collection survey, which shows that Cardiff is will give you a flavour of what’s on offer now the seventh most popular UK in Cardiff, the capital of Wales. 18 Cardiff’s Capital Appeal conference destination. 20 Small, Regular or Large 22 Why Choose Cardiff? 31 Incentives Galore 32 #MCCR 38 Programme Ideas 40 Tourist Information Centre 41 Ideas & Suggestions 43 Cardiff’s A to Z & Cardiff’s Top 10 CF10 T H E S L E A CARDIFF S I S T E N 2018 N E T S 2019 I A S DD E L CAERDY S CARDIFF CAERDYDD | meetincardiff.com | #MeetinCardiff E 4 H ROAD T 4UW RAIL ESSENTIAL INFORMATION AIR CARDIFF – THE CAPITAL OF WALES Aberdeen Location: Currency: E N T S S I E A South East Wales British Pound Sterling L WELCOME! A90 E S CROESO! Population: Phone Code: H 18 348,500 Country code 44, T CR M90 Area code: 029 20 EDINBURGH DF D GLASGOW M8 C D Language: Time Zone: A Y A68 R D M74 A7 English and Welsh Greenwich Mean Time D R I E Newcastle F F • C A (GMT + 1 in summertime) CONTACT US A69 BELFAST Contact: Twinned with: Meet in Cardiff team M6 Nantes – France, Stuttgart – Germany, Xiamen – A1 China, Hordaland – Norway, Lugansk – Ukraine Address: Isle of Man M62 Meet in Cardiff M62 Distance from London: DUBLIN The Courtyard – CY6 LIVERPOOL Approximately 2 hours by road or train. -

SUBMISSION of MARTIN EVANS to the PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE of the NATIONAL ASSEMBLY for WALES - CARDIFF/ANGLESEY AIR SERVICE Background

SUBMISSION OF MARTIN EVANS TO THE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY FOR WALES - CARDIFF/ANGLESEY AIR SERVICE Background Martin Evans is a Visiting Fellow at the University of South Wales. In 2008, working with the Wales Transport Research Centre at the University and Halcrow, he undertook the first year monitoring report of the Cardiff/Anglesey air service on behalf of the Welsh Government. No further monitoring reports have been published by the Welsh Government. Introduction The possibility of Welsh internal air services was proposed in „The Future of Air Transport - Wales‟ White Paper published by the UK Department for Transport in 2003. A feasibility study was undertaken by The Welsh Government and published in the form of a consultation in 2004. The consultation document examined the feasibility of a number of different networks for Welsh internal air services and the level of investment required for the necessary infrastructure. There are no internal air routes in Wales that would be viable if operated on a commercial basis. The Welsh Government acquired the powers to fund internal air services under a Public Service Obligation (PSO) in the Transport (Wales) Act 2006. The conditions to be followed in funding a PSO route are set out in Article 16 of the Air Services Regulations 1008/2008 of the European Union. “3. The necessity and the adequacy of an envisaged public service obligation shall be assessed by the Member State(s) having regard to: a) the proportionality between the envisaged obligation and the economic needs of the region concerned; b) the possibility of having recourse to other modes of transport and the ability of such modes to meet the transport needs under consideration, in particular when existing rail services serve the envisaged route with a travel time of less than three hours and with sufficient frequencies, connections and suitable timings; c) the air fares and conditions which can be quoted to users; d) the combined effect of all air carriers operating or intending to operate on the route. -

GROWING INTERNATIONAL SALES Global Segmentation Toolkit Using Segmentation to Win International Sales CONTENTS

GROWING INTERNATIONAL SALES Global Segmentation Toolkit Using segmentation to win international sales CONTENTS − Introduction − Culturally Curious − Social Energisers − Great Escapers − Understanding experiential tourism − The experience wheel − The 5 stage digital consumer journey − Direct and indirect sales channels − Overview − Air and ferry routes − Snapshot of the market − 5 steps to developing your sales plan − Overseas sales action plan template − Fáilte Ireland − Tourism Ireland INTRODUCTION In 2013 Irish tourism saw a significant and well deserved growth in overseas visitor numbers with many markets now back or close to peak performance levels. Overall growth of 7.2% in 2013 was reflected in an increase from Great Britain (GB) of +5.6%, the United States (US) +14.5%, Germany + 7.7% and France + 9.4%. For the first nine months of 2013, corresponding overseas revenue grew by +13% and holidaymakers by +13%. With growth of +11% between December 2013 and February 2014, the positive start to 2014 is reflected in all the main source markets; visitors from North America (US & Canada) have increased by +17%; GB +14%; Germany +16% and France + 5%. Tourism Ireland’s target for 2014 is 8.2m overseas visitors, an increase of 1 million over 2013. While the trading environment in most source markets remains challenging there are positive indicators. To secure this growth Ireland must win additional market share in the main markets and in a determined effort to do this, the tourism agencies on the island of Ireland are jointly implementing a new, evidence-based consumer global segmentation model. This model provides new, unique insights about the key consumer segments; their motivations, the kinds of experiences they will buy, associated market differentiators and the key channel intermediaries they use. -

Scan 2015-11

SCrjtrjrjj-j 5 j jf ne v/5 November 2015!!!£3.20 ■y) Cover picture: LX-VCM Boeing 747-8R7F (cn 61169/1522) is the 13th and second last 747-8F of the current Cargolux order and is seen at Prestwick on 30 September 2015 in “cutaway” special livery, celebrating the airline’s 45th anniversary.!! ! Lewis Grant 50 years 1965-2015 NO 430 Scottish Air News N995M Bombardier BD700-1A10 Global Express (cn 9322) on ‘Charlie’ with N526EE Gulfstream 4 (cn 1304) both Dunhill Golf Tournament visitors at Dundee on 29 September 2015.!! ! John Chalmers Qli "" ill'' ' ini'i^iV"1 wMjrii"1 f " BM — — , - ••■v.. „s, "• . •' '..if— ... aSraSw \ (VP-BRV) Boeing 737-528 cn 25227/2018, ex Yamal Ailines and Air France, has been positioned for use as a restaurant at a Go Kart Centre in Montrose Avenue Hillington Industrial Estate, Glasgow, and is seen soon after arrival from Kemble store on 14 October 2015.!!! Peter McCann - • i u o a • • « « « h „ smm L ?«* . i < < bB ZE708 BAe146 C.3 (cn 2211) is seen at Prestwick on 30 September 2015. Operated by 32 Sqn, the 5rvY aircraft was initially used in Afghanistan, and is• •• formerly OO-TAY of TNT Airways and one time Edinburgh regular.!!!!!!!!!! Lewis Grant ^ -- V amm Scottish Air News NO 431 scottish air news November 2015 Volume 50 MANAGING EDITOR Paul Wiggins E Mail : [email protected] Editorial Address : Grinsdale House, Grinsdale, Carlisle, CA5 6DS NEWS SECTION RESIDENTS SECTION Jim Fulton Alistair Ness E Mail : [email protected] E Mail : [email protected] MILITARY SECTION WEBSITE UPDATES AND QUERIES Vacancy, copy to Paul Wiggins meantime Scott Jamieson E Mail : [email protected] AIRFIELDS SCANNED SUB-EDITORS Aberdeen Ian Grierson Edinburgh Sandy Benzies / Alistair Ness Dundee / Perth Tim Gulson Glasgow Alan Reid Highlands/Islands Alan Nightingale Inverness Stephen Lane Prestwick Alan McKnight PHOTO SUBMISSIONS Please send photos via e-mail to Lorence Fizia , e-mail address is scanphotos1gmail.com Photos should be high quality JPEGs, uncompressed straight from the camera, and in colour. -

Public Accounts Committee

------------------------ Public Document Pack ------------------------ Agenda - Public Accounts Committee Meeting Venue: For further information contact: Committee Room 3 - Senedd Fay Buckle Meeting date: Thursday, 11 February Committee Clerk 2016 0300 200 6565 Meeting time: 09.00 [email protected] 1 Introductions, apologies and substitutions (09.00) 2 Papers to note (09.00) Intra-Wales - Cardiff to Anglesey - Air Service: Letter from Simon Jones, Welsh Government - 27 January 2016 (Pages 1 - 3) Glastir: Letter from Matthew Quinn, Welsh Government - 1 February 2016 (Pages 4 - 6) 3 Cardiff Airport: Evidence Session 3 (09.00-10.30) (Pages 7 - 26) Research Briefing Welsh Government James Price – Deputy Permanent Secretary, Economy, Skills and Natural Resources Group, Welsh Government 4 Cardiff Airport: Evidence Session 4 (10.30-11.30) (Pages 27 - 178) PAC(4)-06-16 P1 PAC(4)-06-16 P2 Research Briefing Aviation and Transport Experts Chris Cain – Director and Head of Research, Northpoint Aviation Professor Stuart Cole CBE - Emeritus Professor of Transport Economics and Policy, University of South Wales (Break 11.30-11.40) 5 Cardiff Airport: Evidence Session 5 (11.40-12.40) (Pages 179 - 190) Research Briefing Transport Scotland John Nicholls, Director – Aviation, Maritime, Freight and Canals Transport Scotland Andrew Miller, Chair of Glasgow Prestwick Airport 6 Motion under Standing Order 17.42 to resolve to exclude the public from the meeting for the following business: (12.40) Item 7 7 Cardiff Airport: Consideration of evidence received (12.40-13.00) Y Pwyllgor Cyfrifon Cyhoeddus | Public Accounts Committee PAC(4)-06-16 PTN1 Agenda Item 2.1 Adran yr Economi, Gwyddoniaeth a Thrafnidiaeth Department for Economy, Science and Transport Darren Millar AM Chair – Public Accounts Committee National Assembly for Wales Cardiff Bay Cardiff CF99 1NA 27 January 2016 Dear Mr Millar I am writing to follow up on your letter dated 5 November to James Price requesting further information on the Intra Wales Air Service. -

Cardiff to Anglesey – Air Service Memorandum for the Public Accounts Committee Intra-Wales – Cardiff to Anglesey – Air Service

January 2014 www.wao.gov.uk Intra-Wales – Cardiff to Anglesey – Air Service Memorandum for the Public Accounts Committee Intra-Wales – Cardiff to Anglesey – Air Service Report presented by the Auditor General for Wales to the National Assembly for Wales I have prepared this report for presentation to the National Assembly under the Government of Wales Act 2006. The Wales Audit Office team who assisted me in preparing this report comprised Jeremy Morgan and Matthew Mortlock under the direction of Gillian Body. Huw Vaughan Thomas Auditor General for Wales Wales Audit Office 24 Cathedral Road Cardiff CF11 9LJ The Auditor General is totally independent of the National Assembly and Welsh Government. He examines and certifies the accounts of the Welsh Government and its sponsored and related public bodies, including NHS bodies in Wales. He also has the statutory power to report to the National Assembly on the economy, efficiency and effectiveness with which those organisations have used, and may improve the use of, their resources in discharging their functions. The Auditor General also appoints auditors to local government bodies in Wales, conducts and promotes value for money studies in the local government sector and inspects for compliance with best value requirements under the Wales Programme for Improvement. However, in order to protect the constitutional position of local government, he does not report to the National Assembly specifically on such local government work, except where required to do so by statute. The Auditor General and his staff together comprise the Wales Audit Office. For further information about the Wales Audit Office please write to the Auditor General at the address above, telephone 029 2032 0500, email: [email protected], or see web site www.wao.gov.uk © Auditor General for Wales 2014 You may re-use this publication (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium. -

Air Passenger Duty: Implications for Northern Ireland

House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee Air Passenger Duty: implications for Northern Ireland Second Report of Session 2010–12 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 5 July 2011 HC 1227 Published on 8 July 2011 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Northern Ireland Affairs Committee The Northern Ireland Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Northern Ireland Office (but excluding individual cases and advice given by the Crown Solicitor); and other matters within the responsibilities of the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland (but excluding the expenditure, administration and policy of the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions, Northern Ireland and the drafting of legislation by the Office of the Legislative Counsel). Current membership Mr Laurence Robertson MP (Conservative, Tewkesbury) (Chair) Mr Joe Benton MP (Labour, Bootle) Oliver Colvile MP (Conservative, Plymouth, Sutton and Devonport) Mr Stephen Hepburn MP (Labour, Jarrow) Lady Hermon MP (Independent, North Down) Kate Hoey MP (Labour, Vauxhall) Ian Lavery MP (Labour, Wansbeck) Naomi Long MP (Alliance, Belfast East) Jack Lopresti MP (Conservative, Filton and Bradley Stoke) Dr Alasdair McDonnell MP (SDLP, Belfast South) Ian Paisley MP (DUP, North Antrim) David Simpson MP (DUP, Upper Bann) Mel Stride MP (Conservative, Central Devon) Gavin Williamson MP (Conservative, South Staffordshire) The following Member was also a member of the Committee during the Parliament: Stephen Pound MP (Labour, Ealing North) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. -

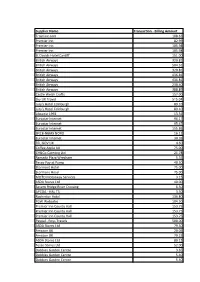

Supplier Name Transaction

Supplier Name Transaction - Billing Amount Trainline.com 108.63 Premier Inn 82.99 Premier Inn 105.98 Premier Inn 105.98 St Davids Hotel Cardiff 151.00 British Airways 320.81 British Airways 504.51 British Airways 320.81 British Airways 436.81 British Airways 436.81 British Airways 230.40 British Airways 388.89 Castle Welsh Crafts 157.00 Sky UK Travel 515.04 Jury's Hotel Edinburgh 89.10 Jury's Hotel Edinburgh 89.10 Librairie 1992 13.31 Eurostar Internet 96.17 Eurostar Internet 95.47 Eurostar Internet 155.86 SNCB-NBMS NORD 16.12 Eurostar Internet 30.39 TFL.GOV.UK 4.60 Coffee Apple UK 75.00 CH&Co Catering Ltd 21.78 Ramada Plaza Wrexham 5.55 Tesco Pay at Pump 40.50 Stormont Hotel 75.00 Stormont Hotel 75.00 MOTO Motorway Services 3.15 ASDA Stores Ltd 40.00 Severn Bridge River Crossing 6.50 APCOA - HAL T5 3.50 Rochester Hotel 136.80 FGW Websales 104.50 Premier Inn County Hall 153.75 Premier Inn County Hall 153.75 Premier Inn County Hall 153.75 Paypal - Roys Travels 500.00 ASDA Stores Ltd 79.50 Amazon UK 20.05 Amazon UK 79.23 ASDA Stores Ltd 80.15 Tesco Stores Ltd 52.00 Dobbies Garden Centre 3.65 Dobbies Garden Centre 5.40 Dobbies Garden Centre 5.40 Sainsburys Supermarket's Ltd 37.00 Sainsburys Supermarket's Ltd 6.30 Lion Quays Hotel 105.00 Lion Quays Hotel 105.00 Lion Quays Hotel 210.00 Lion Quays Hotel 50.45 CIPP 130.00 Amazon UK 74.79 Trainline 223.38 Royal Kings Arms Hotel 65.00 Amazon UK 570.00 Ellingham House, Colwyn Bay 69.00 Arriva Trains Wales 63.00 AAT (Accounting) 139.00 SurveyMonkey.com 299.00 Amazon UK 55.94 Amazon UK 38.80 B&Q 7.90 -

Adolygiad O'r Rhwymedigaeth Gwasanaeth Cyhoeddus – Dyfodol Hirdymor

NPS-PS-0027-15 Fframwaith Gwasanaethau Proffesiynol –Ymgynghoriaeth Adeiladu (Seilwaith ac Ystadau) – Hedfan Adolygiad o'r Rhwymedigaeth Gwasanaeth Cyhoeddus – Dyfodol Hirdymor Cefnogir gan Northpoint Aviation Services rpsgroup.com/uk Teitl: Adolygiad o'r Rhwymedigaeth Gwasanaeth Cyhoeddus – Dyfodol Hirdymor Dyddiad: 11 Hydref 2017 Ein Cyf: NK018661\GDD RPS Planning & Development Sherwood House Sherwood Avenue Newark Nottinghamshire NG24 1QQ Ffôn: 01636 605700 E-bost: [email protected] RHEOLI ANSAWDD Paratowyd gan: RPS Awdurdodwyd gan: RPS Dyddiad: 16 Tachwedd 2017 Rhif y Prosiect/ NK018661 Cyfeirnod y Ddogfen: Hanes Diwygio Diw. Dyddiad Disgrifiad Awdur Gwiriwyd 17/2/2017 Drafft Gweithredol Cyntaf CC BoF 4/3/2017 Drafft Gweithredol wedi'i wirio a'i fformatio FoF BoF Drafft Gweithredol wedi'i adolygu yn dilyn adborth 20/7/2017 FoF BoF cleientiaid 29/09/17 Addasiadau i'r fformat APa GDD 03/10/17 Cywiriadau a diweddariadau APa GDD HAWLFRAINT © RPS Mae'r deunydd yn yr adroddiad hwn yn gyfrinachol. Mae'r adroddiad hwn wedi'i baratoi at ddefnydd RPS Planning & Development yn unig ac ni chaiff ei ddosbarthu na'i ddarparu i unrhyw gwmni nac unigolyn heb i RPS gael gwybod a rhoi caniatâd ysgrifenedig. CYNNWYS CRYNODEB GWEITHREDOL ................................ ................................ ................................ .......................... 1 Canfyddiadau, Casgliadau ac Argymhellion ......................................................................................... 6 Argymhellion i'w Gweithredu ar Unwaith: ......................................................................................... -

Cardiff to Anglesey - Air Service: Final Report

National Assembly for Wales Public Accounts Committee Intra-Wales - Cardiff to Anglesey - Air Service: Final Report July 2015 The National Assembly for Wales is the democratically elected body that represents the interests of Wales and its people, makes laws for Wales and holds the Welsh Government to account. An electronic copy of this report can be found on the National Assembly’s website: www.assembly.wales Copies of this report can also be obtained in accessible formats including Braille, large print; audio or hard copy from: Public Accounts Committee National Assembly for Wales Cardiff Bay CF99 1NA Tel: 0300 200 6565 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @SeneddPAC © National Assembly for Wales Commission Copyright 2015 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading or derogatory context. The material must be acknowledged as copyright of the National Assembly for Wales Commission and the title of the document specified. National Assembly for Wales Public Accounts Committee Intra-Wales - Cardiff to Anglesey - Air Service: Final Report July 2015 Public Accounts Committee The Committee was established on 22 June 2011. The role of the Public Accounts Committee is to ensure that proper and thorough scrutiny is given to Welsh Government expenditure. The specific functions of the Committee are set out in Standing Order 18. The Committee will consider reports prepared by the Auditor General for Wales on the accounts of the Welsh Government and other public bodies, and on the economy, efficiency and effectiveness with which resources were employed in the discharge of public functions. -

Review of the PSO – Long Term Future

NP S-PS-0027-15 Professional Services Framework – Construction Consultancy (Infrastructure and Estates) – Aviation Review of the PSO – Long Term Future Summary Report Supported by Northpoint Aviation Services rpsgroup.com/uk Title: Review of the PSO – Long Term Future Date: 11 October 2017 Our Ref: NK018661\GDD RPS Planning & Development Sherwood House Sherwood Avenue Newark Nottinghamshire NG24 1QQ Tel: 01636 605700 Email: [email protected] QUALITY MANAGEMENT Prepared by: RPS Authorised by: RPS Date: 16 November 2017 Project Number/ NK018661 Document Reference: Revision History Rev. Date Description Author Checked 17/2/2017 First Working Draft CC BoF 4/3/2017 Working Draft checked and formatted FoF BoF 20/7/2017 Working Draft Reviewed in light of client feedback FoF BoF 29/09/17 Format adjustments APa GDD 03/10/17 Corrections and updates APa GDD COPYRIGHT © RPS The material presented in this report is confidential. This report has been prepared for the exclusive use of RPS Planning & Development and shall not be distributed or made available to any other company or person without the knowledge and written consent of RPS. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................... 1 Findings, Conclusions and Recommendations .................................................................................... 4 Immediate Recommendations: .......................................................................................................... -

Airportwatch Bulletin 76 April 2015

AirportWatch bulletin 76 April 2015 Page 1. Page 7. - Gatwick opposition groups and MPs hand in letter to - Crispin Blunt MP: Too many unanswered questions make Downing Street, asking PM to recognise devastating Gatwick obviously NOT the right choice impact of Gatwick runway - To conceal the real number of aircraft noise complaints, - Heathrow opposition rally shows united cross-party Gatwick now just records one per person per day rejection of 3rd runway - Launch of the Global Anti-Aerotropolis Movement (GAAM) as the number of planned Aerotropolis Page 2. developments is rising fast - Boris turns down London City Airport expansion plans on noise grounds Page 8. - Committee on Climate Change writes to Sir Howard - Ryanair announce to Stock Exchange it has “not to say aviation CO2 emissions must not be over 2005 level considered or approved any transatlantic project and does by 2050 not intend to do so.” - Manchester Airport says it is the main airport for the north Page 3. – Heathrow expansion is not needed for the regions - Heathrow says it did not know flight path changes were continuing – blames NATS for not telling them Page 9. - Windsor MP, Adam Afriye, says on NATS/flightpath - Firm behind report calling for a 50% cut in APD – York fiasco, Heathrow has either been wilfully misleading or Aviation – linked to airlines. Hence bias. incompetent - In USA the FAA‟s new air traffic control system NextGen - Heathrow would spend £10 million to increase some is causing major noise pollution domestic flights (only with a 3rd runway) to get backing - Stobart have applied for £56 million government funding from regions for 3 domestic routes from Carlisle Page 4.