Redalyc.The Xenarthrans of Nicaragua. Los Xenarthra De

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tabbitha Schliesman Tolypeutes Matacus Southern Three-Banded Armadillo

Tabbitha Schliesman Tolypeutes matacus Southern Three-banded Armadillo Description: The Southern Three-Banded Armadillo, Tolypeutes matacus, is a small creature, about 10- 15 cm tall, 21 – 30 cm long(Eisenburg & Redford, 1999), and 1.00 to 1.59 kg in weight (EOL, 2014). The outer shell of the Southern Three-Banded Armadillo ranges from light brownish-yellow to blackish-brown in coloring. This armadillo is comprised of three parts: a head, body, and an immobile, stout tail that are heavily armored with a leathery, think shell(Ellis, 1999). This leathery armor covers the entire animal, except for the belly and ears, when walking and/or standing. The skin of the front and rear portions of the Southern Three-Banded Armadillo are not attached to the middle section, allowing the animal to roll into a tight ball(EOL, 2014). Other features that make the Southern Three-Banded Southern Three Banded-Armadillo, Tolypeutes Armadillo distinct are the third and fourth claws of matacus, (Smith, 2007). the hind feet that look like hooves, while the front feet have only three sharp powerful claws(Superina, 2009). Southern Three-Banded Armadillos have a long pink tongue that is usually sticky. Their heads are long, and are unique to each armadillo; like humans’ fingerprints, researchers have used their head patterns while tracking them to identify which individual armadillo they are researching(HZ, 2011). Ecology: Southern Three-Banded Armadillos are native to north central Argentina, east central Bolivia and multiple sections of Paraguay and south west Brazil. The Southern Three-Banded Armadillo is found mainly in scrub forests and savannahs in these sections of South America. -

Reveals That Glyptodonts Evolved from Eocene Armadillos

Molecular Ecology (2016) 25, 3499–3508 doi: 10.1111/mec.13695 Ancient DNA from the extinct South American giant glyptodont Doedicurus sp. (Xenarthra: Glyptodontidae) reveals that glyptodonts evolved from Eocene armadillos KIEREN J. MITCHELL,* AGUSTIN SCANFERLA,† ESTEBAN SOIBELZON,‡ RICARDO BONINI,‡ JAVIER OCHOA§ and ALAN COOPER* *Australian Centre for Ancient DNA, School of Biological Sciences, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia, †CONICET-Instituto de Bio y Geociencias del NOA (IBIGEO), 9 de Julio No 14 (A4405BBB), Rosario de Lerma, Salta, Argentina, ‡Division Paleontologıa de Vertebrados, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo (UNLP), CONICET, Museo de La Plata, Paseo del Bosque, La Plata, Buenos Aires 1900, Argentina, §Museo Arqueologico e Historico Regional ‘Florentino Ameghino’, Int De Buono y San Pedro, Rıo Tercero, Cordoba X5850, Argentina Abstract Glyptodonts were giant (some of them up to ~2400 kg), heavily armoured relatives of living armadillos, which became extinct during the Late Pleistocene/early Holocene alongside much of the South American megafauna. Although glyptodonts were an important component of Cenozoic South American faunas, their early evolution and phylogenetic affinities within the order Cingulata (armoured New World placental mammals) remain controversial. In this study, we used hybridization enrichment and high-throughput sequencing to obtain a partial mitochondrial genome from Doedicurus sp., the largest (1.5 m tall, and 4 m long) and one of the last surviving glyptodonts. Our molecular phylogenetic analyses revealed that glyptodonts fall within the diver- sity of living armadillos. Reanalysis of morphological data using a molecular ‘back- bone constraint’ revealed several morphological characters that supported a close relationship between glyptodonts and the tiny extant fairy armadillos (Chlamyphori- nae). -

Dietary Specialization and Variation in Two Mammalian Myrmecophages (Variation in Mammalian Myrmecophagy)

Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 59: 201-208, 1986 Dietary specialization and variation in two mammalian myrmecophages (variation in mammalian myrmecophagy) Especializaci6n dietaria y variaci6n en dos mamiferos mirmec6fagos (variaci6n en la mirmecofagia de mamiferos) KENT H. REDFORD Center for Latin American Studies, Grinter Hall, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611, USA ABSTRACT This paper compares dietary variation in an opportunistic myrmecophage, Dasypus novemcinctus, and an obligate myrmecophage, Myrmecophaga tridactyla. The diet of the common long-nosed armadillo, D. novemcintus, consists of a broad range of invertebrate as well as vertebrates and plant material. In the United States, ants and termites are less important as a food source than they are in South America. The diet of the giant anteater. M. tridactyla, consists almost entirely of ants and termites. In some areas giant anteaters consume more ants whereas in others termites are a larger part of their diet. Much of the variation in the diet of these two myrmecophages can be explained by geographical and ecological variation in the abundance of prey. However, some variation may be due to individual differences as well. Key words: Dasypus novemcinctus, Myrmecophaga tridactyla, Tamandua, food habits. armadillo, giant anteater, ants, termites. RESUMEN En este trabajo se compara la variacion dietaria entre un mirmecofago oportunista, Dasypus novemcinctus, y uno obligado, Myrmecophaga tridactyla. La dieta del armadillo comun, D. novemcinctus, incluye un amplio rango de in- vertebrados así como vertebrados y materia vegetal. En los Estados Unidos, hormigas y termites son menos importantes como recurso alimenticio de los armadillos, de lo que son en Sudamérica. La dieta del hormiguero gigante, M tridactyla, está compuesta casi enteramente por hormigas y termites. -

Xenarthrans: 'Aliens'

Vet Times The website for the veterinary profession https://www.vettimes.co.uk XENARTHRANS: ‘ALIENS’ ON EARTH Author : JONATHAN CRACKNELL Categories : Vets Date : August 4, 2008 JONATHAN CRACKNELL finds that hanging around with sloths and their fellow Xenarthrans offers up exciting challenges XENARTHRANS: the name sounds like a race from a low-budget science fiction film. This is actually a super-order of mammals that get their name from their “alien” joint, which is exhibited in the vertebral joints. The Xenarthrans include 31 living species: six species of sloth, four anteaters and 21 species of armadillos – all of which originated in South America. Historically, these animals were classified within the order Edentata (meaning “without teeth”), which included pangolins and aardvarks. It was realised that this was a polyphyletic group, containing unrelated families. Therefore, the Xenarthra order was created. The Xenarthrans are a well-represented order in captivity, with banded armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus) becoming one of the new “exotic” exotics to be presented to clinicians. In zoological collections, giant anteaters (Myrmecophaga tridactyla), southern tamanduas (Tamandua tetradactyla), and sloths (typically the southern two-toed sloth – Choloepus didactylus – although others are present) are among the more common species housed in captivity. Every species has its own needs and oddities. With this brief review of each species, the author will look at basic anatomy and physiology, along with a quick review of some of the more commonly reported complaints for this group of animals. 1 / 14 Giant anteater The giant anteater’s most obvious feature is its long tongue and bushy tail. They are approximately 1.5 to two metres long and weigh in the region of 18kg to 45kg. -

Introduction Recent Classifications Regard the Order Pilosa, Anteaters

Introduction Recent classifications regard the order Pilosa, anteaters and sloths, and order Cingulata, the armadillos, within the superorder Xenarthra meaning “strange joints”. In the past, Pilosa and Cingulata wer regarded as suborders of the order Xenarthra, with the armadillos. Earlier still, both armadillos and pilosans were classified together with pangolins and the aardvark as the order Edentata meaning “toothless”. The orders Pilosa and Cingulata are distinguishable as the cingulatas have an armoured upper body and the pilosa have fur. Studies have concluded that sloths, anteaters, and armadillos diverged at least 75-80 million years ago and that they are as different from one another as are carnivores, bats and primates. The Pilosa are now considered almost exclusively a New World order, however, fossil records indicate that they were once found in Europe and possibly Asia. This order may have been distributed worldwide in the Cretaceous period, but became limited to South America and have remained there for most of their history and evolved into numerous groups. The Pilosa were once far more diverse than they are today; there are known to be 10 times as many fossil as living genera. The superorder is distinguished from all others by what are known as the xenarthrous vertebrae. There are secondary and sometimes even more, articulations between the vertebrae of the lumbar (lower back) series. In other words, consecutive vertebrae connect in more than one place. In addition, the pelvis connects with more of the spine than in other mammals. These adaptations to the spine give support, particularly to the hips. The name Xenarthra refers to this peculiarity of the spine and modem taxonomy places these three groups of animals together, even though they are very different from one another and they are highly specialized. -

The Giant Armadillo of the Gran Chaco

The Giant Armadillo of the Gran Chaco A giant armadillo Priodontes maximus at the Saenz-Peña Zoo in South America raises up, balancing with its tail, a common posture for this large species. Venezuela The Guianas: Guyana hat’s the size of Texas and Arizona combined, reaches temperatures Suriname French Guiana Wof 115 degrees Fahrenheit, has plants with 15-inch-long thorns, Colombia and houses an armadillo larger than a coffee table? The South American Gran Chaco, where giant armadillos wander freely. The Gran Chaco region covers more than 1 million square kilometers of Argentina, Bolivia, Perú Brazil Paraguay, and Brazil, with approximately 60 percent in Argentina and Bolivia just 7 percent in Brazil. The region is a mosaic of grasslands, savannas, Paraguay • open woodlands, dry thorn forests, and gallery forests that provide a GRAN CHACO 15 range of habitats where some diverse animal species flourish. • In the gallery forests of the humid Chaco, we regularly encounter animals Argentina that are associated with tropical and subtropical forests, like jaguars, owl monkeys, howler monkeys, peccaries, deer, tapirs, and various kinds of eden- tates, a group of mammals that includes sloths, anteaters, and armadillos. The Gran Chaco—from the Quechua Although there are no sloths in the Chaco, we regularly find lesser anteaters 2003 and sometimes come across giant anteaters. Both the nine-banded armadillo, Indian language of Bolivia for “great hunting ground”—crosses four coun- also found in Texas, and the tatu bola, or three-banded armadillo, which you tries and encompasses an area the can see at the Wild Animal Park’s Animal Care Center and the San Diego Zoo’s size of Texas and Arizona combined. -

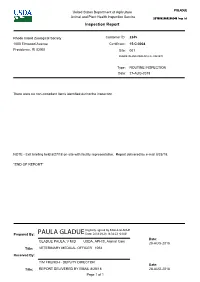

Inspection Report

PGLADUE United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service 2016082569255248 Insp_id Inspection Report Rhode Island Zoological Society Customer ID: 2245 1000 Elmwood Avenue Certificate: 15-C-0004 Providence, RI 02907 Site: 001 RHODE ISLAND ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY Type: ROUTINE INSPECTION Date: 27-AUG-2018 There were no non-compliant items identified during the inspection. NOTE - Exit briefing held 8/27/18 on-site with facility representative. Report delivered by e-mail 8/28/18. *END OF REPORT* Prepared By: Date: GLADUE PAULA, V M D USDA, APHIS, Animal Care 28-AUG-2018 Title: VETERINARY MEDICAL OFFICER 1054 Received By: TIM FRENCH - DEPUTY DIRECTOR Date: Title: REPORT DELIVERED BY EMAIL 8/28/18 28-AUG-2018 Page 1 of 1 United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 2245 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 27-AUG-18 Species Inspected Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 2245 15-C-0004 001 RHODE ISLAND ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY 27-AUG-18 Count Scientific Name Common Name 000004 Acinonyx jubatus CHEETAH 000002 Ailurus fulgens RED PANDA 000002 Alouatta caraya BLACK HOWLER 000003 Ammotragus lervia BARBARY SHEEP 000004 Antilocapra americana PRONGHORN 000002 Arctictis binturong BINTURONG 000003 Artibeus jamaicensis JAMAICAN FRUIT-EATING BAT / JAMAICAN FRUIT BAT 000004 Atelerix albiventris FOUR-TOED HEDGEHOG (MOST COMMON PET HEDGEHOG) 000001 Babyrousa babyrussa BABIRUSA 000003 Bison bison AMERICAN BISON 000002 Bos taurus CATTLE / COW / OX / WATUSI 000001 Budorcas taxicolor TAKIN 000003 Callicebus -

A Note on the Climbing Abilities of Giant Anteaters, Myrmecophaga Tridactyla (Xenarthra, Myrmecophagidae)

BOL MUS BIOL MELLO LEITÃO (N SÉR) 15:41-46 JUNHO DE 2003 41 A note on the climbing abilities of giant anteaters, Myrmecophaga tridactyla (Xenarthra, Myrmecophagidae) Robert J Young1*, Carlyle M Coelho2 and Dalía R Wieloch2 ABSTRACT: In this note we provide seven observations of climbing behaviour by giant anteaters Five observations were recorded in the field: three of giant anteaters climbing on top of 15 to 20 metre high termite mounds, and two observations of giant anteaters in trees In these cases the animals were apparently trying to obtain food The other two observations are from captivity, one involves a juvenile animal that several times over a three month period climbed in a tree to the height of around 20 metres The final observation, involves an adult female that after being separated from her mother climbed on two occasions over a wall with a fence on top (total height 2 metres) to be reunited with her mother It therefore seems that, despite the fact only one other record of climbing behaviour by giant anteaters exists in the scientific literature that giant anteaters have the ability to climb It also may be the case that young adults are highly motivated to stay with their mothers Key words: giant anteater, Myrmecophaga tridactyla, climbing behaviour, wild, zoos RESUMO: Nota sobre as habilidades trepadoras do tamanduá-bandeira, Myrmecophaga tridactyla (Xenarthra, Myrmecophagidae) Nesta nota apresentamos sete registros de comportamento de subir expressado por tamanduá-bandeira Temos cinco exemplos da natureza: três de tamanduás- -

(Dasypus) in North America Based on Ancient Mitochondrial DNA

bs_bs_banner A revised evolutionary history of armadillos (Dasypus) in North America based on ancient mitochondrial DNA BETH SHAPIRO, RUSSELL W. GRAHAM AND BRANDON LETTS Shapiro, B. Graham, R. W. & Letts, B.: A revised evolutionary history of armadillos (Dasypus) in North America based on ancient mitochondrial DNA. Boreas. 10.1111/bor.12094. ISSN 0300-9483. The large, beautiful armadillo, Dasypus bellus, first appeared in North America about 2.5 million years ago, and was extinct across its southeastern US range by 11 thousand years ago (ka). Within the last 150 years, the much smaller nine-banded armadillo, D. novemcinctus, has expanded rapidly out of Mexico and colonized much of the former range of the beautiful armadillo. The high degree of morphological similarity between these two species has led to speculation that they might be a single, highly adaptable species with phenotypical responses and geographical range fluctuations resulting from environmental changes. If this is correct, then the biology and tolerance limits for D. novemcinctus could be directly applied to the Pleistocene species, D. bellus. To investigate this, we isolated ancient mitochondrial DNA from late Pleistocene-age specimens of Dasypus from Missouri and Florida. We identified two genetically distinct mitochondrial lineages, which most likely correspond to D. bellus (Missouri) and D. novemcinctus (Florida). Surprisingly, both lineages were isolated from large specimens that were identified previously as D. bellus. Our results suggest that D. novemcinctus, which is currently classified as an invasive species, was already present in central Florida around 10 ka, significantly earlier than previously believed. Beth Shapiro ([email protected]), Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA; Russell W. -

The Ancestral Eutherian Karyotype Is Present in Xenarthra

The Ancestral Eutherian Karyotype Is Present in Xenarthra Marta Svartman*, Gary Stone, Roscoe Stanyon Comparative Molecular Cytogenetics Core, Genetics Branch, National Cancer Institute-Frederick, Frederick, Maryland, United States of America Molecular studies have led recently to the proposal of a new super-ordinal arrangement of the 18 extant Eutherian orders. From the four proposed super-orders, Afrotheria and Xenarthra were considered the most basal. Chromosome- painting studies with human probes in these two mammalian groups are thus key in the quest to establish the ancestral Eutherian karyotype. Although a reasonable amount of chromosome-painting data with human probes have already been obtained for Afrotheria, no Xenarthra species has been thoroughly analyzed with this approach. We hybridized human chromosome probes to metaphases of species (Dasypus novemcinctus, Tamandua tetradactyla, and Choloepus hoffmanii) representing three of the four Xenarthra families. Our data allowed us to review the current hypotheses for the ancestral Eutherian karyotype, which range from 2n ¼ 44 to 2n ¼ 48. One of the species studied, the two-toed sloth C. hoffmanii (2n ¼ 50), showed a chromosome complement strikingly similar to the proposed 2n ¼ 48 ancestral Eutherian karyotype, strongly reinforcing it. Citation: Svartman M, Stone G, Stanyon R (2006) The ancestral Eutherian karyotype is present in Xenarthra. PLoS Genet 2(7): e109. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020109 Introduction Megalonychidae (two species of two-toed sloth), and Dasypo- didae (about 20 species of armadillo) [6–9]. According to Extensive molecular data on mammalian genomes have led molecular data estimates, the radiation of Xenarthra recently to the proposal of a new phylogenetic tree for occurred around 65 mya, during the Cretaceous/Tertiary Eutherians, which encompasses four super-orders: Afrotheria boundary. -

Nine-Banded Armadillo (Dasypus Novemcinctus) Michael T

Nine-banded Armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) Michael T. Mengak Armadillos are present throughout much of Georgia and are considered an urban pest by many people. Armadillos are common in central and southern Georgia and can easily be found in most of Georgia’s 159 counties. They may be absent from the mountain counties but are found northward along the Interstate 75 corridor. They have poorly developed teeth and limited mobility. In fact, armadillos have small, peg-like teeth that are useful for grinding their food but of little value for capturing prey. No other mammal in Georgia has bony skin plates or a “shell”, which makes the armadillo easy to identify. Just like a turtle, the shell is called a carapace. Only one species of armadillo is found in Georgia and the southeastern U.S. However, 20 recognized species are found throughout Central and South America. These include the giant armadillo, which can weigh up to 130 pounds, and the pink fairy armadillo, which weighs less than 4 ounces. Taxonomy Order Cingulata – Armadillos Family Dasypodidae – Armadillo Nine-banded Armadillo – Dasypus novemcinctus The genus name Dasypus is thought to be derived from a Greek word for hare or rabbit. The armadillo is so named because the Aztec word for armadillo meant turtle-rabbit. The species name novemcinctus refers to the nine movable bands on the middle portion of their shell or carapace. Their common name, armadillo, is derived from a Spanish word meaning “little armored one.” Figure 1. Nine-banded Armadillo. Photo by author, 2014. Status Armadillos are considered both an exotic species and a pest. -

Scientists Astonished to Find Six New Species of Silky Anteater Hiding in Pl

Scientists astonished to find six new species of silky anteater hiding in pl... https://www.haaretz.com/science-and-health/MAGAZINE-scientists-find... Israel News All Germany - Israel Lebanon war Iran Gaza plan State of the Union Poland - Holocaust Log in One of the seven silky anteater species drowsing in a tree, which is where it spends its life when not actually dining on ants Credit: Pedro Da Costa Silva, Karina Molina and Alexandre Martins By Ruth Schuster | Dec 15, 2017 Share Tweet 0 Zen Subscribe ● ● ● 1 de 5 31/01/2018 18:09 Scientists astonished to find six new species of silky anteater hiding in pl... https://www.haaretz.com/science-and-health/MAGAZINE-scientists-find... Israel News All Germany - Israel Lebanon war Iran Gaza plan State of the Union Poland - Holocaust Log in Scientists had thought that the silky anteater was a single species. Now having actually looked at the tiny animals, who spend most of their lives asleep in trees in remote parts of Central and South America, they realize there are seven species. At least. Following a decade of expeditions and analysis, a Brazilian team reports on the validation of three previously suspected silky anteater species and the addition of three more in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. Altogether with the originally known one, that makes seven silky anteaters. There could be dozens of species of silky anteaters – who knows. Not a lot of zoologists live in rain forest treetops and these things are strictly nocturnal, and small. Not that the animals, also called pygmy anteaters, are easy to see in broad sunlight.