35 Having Reviewed Hundreds of Press Reports on School Shootings Since 2000, I Find a Consistent Pattern of Narrative Speculatio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

Bibliography This bibliography catalogs all sources to which direct citations have been made. Other references influenced my thinking and helped me to understand my subject more clearly, and researchers who assisted me used yet others in compiling notes. A complete bibliography that includes all such titles may be found online at http://www.andrew solomon.org/far-from-the-tree/bibliography. Abbott, Douglas A., and William H. Meredith. “Strengths of parents with retarded children.” Family Relations 35, no. 3 ( July 1986): 371–75. Abbott, Jack Henry. In the Belly of the Beast: Letters from Prison. New York: Random House, 1981. Abi-Dargham, Anissa, et al. “Increased baseline occupancy of D2 receptors by dopamine in schizophrenia.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 97, no. 14 ( July 2000): 8104–9. Ablon, Joan. “Dwarfism and social identity: Self-help group participation.”Social Science & Medicine 15B (1981): 25–30. ———. Little People in America: The Social Dimension of Dwarfism. New York: Praeger, 1984. ———. Living with Difference: Families with Dwarf Children. New York: Praeger, 1988. ———. “Personality and stereotypel in osteogenesis imperfecta: Behavioral phenotype or response to life’s hard challenges?” American Journal of Medical Genetics 122A (October 15, 2003): 201–14. Abraham, Willard. Barbara: A Prologue. New York: Rinehart, 1958. Abrahams, Brett S., and Daniel H. Geschwind. “Advances in autism genetics: On the threshold of a new neurobiology.” Nature Review Genetics 9, no. 5 (May 2008): 341–55. Abramsky, Sasha, and Jamie Fellner. Ill-Equipped: U.S. Prisons and Offenders with Mental Illness. New York: Human Rights Watch, 2003. Accardo, Pasquale J., Christy Magnusen, and Arnold J. -

Autism Resources Became One of the Tope Scientists in the Humane Livestock Handling Industry

PICTURE BOOKS YOUNG ADULT FICTION (12 and up) *The following are some of the autism-related materials available at Matawan-Aberdeen Public My Brother Charlie by Holly R. Peete (E PEE) Anything But Typical by Nora Raleigh Baskin Library. Please consult the librarians for further A girl tells what it is like living with her twin brother (YA BASKIN; YA PLAYAWAY BASKIN) assistance or research. who has autism and sometimes finds it hard to Jason, a twelve-year-old autistic boy who wants communicate with words, but who, in most ways, is to become a writer, relates what his life is like as just like any other boy. Includes authors' note about he tries to make sense of his world. PARENTING autism . Al Capone Does My Shirts Asperger Syndrome and High Functioning Autism Since We’re Friends by Celeste Shally (E SHA) by Gennifer Choldenko (YA CHOLDENKO) Tool Kit: A Tool Kit to Assist Families in Getting A boy describes his friendship with Matt, an autistic A twelve-year-old boy named Moose moves to the Critical Information They Need in the First boy, telling how he helps Matt cope with everyday Alcatraz Island in 1935 when guards' families 100 Days After Asperger Syndrome and High situations. were housed there, and has to contend with his Functioning Autism Diagnosis extraordinary new environment in addition to by Autism Speaks (Organization) (618.9285 AU) Looking After Louis by Lesley Ely (E ELY) life with his autistic sister. When a new boy with autism joins their classroom, Healing and Preventing Autism: A Complete the children try to understand his world and to The Very Ordered Existence of Merilee Guide by Jenny McCarthy (618.928 MC) include him in theirs. -

A Phenomenological Study of the Relationship Between Parents and Their Children Diagnosed with an Autism Spectrum Disorder

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2011 Reconstructing Autism: A Phenomenological Study of the Relationship Between Parents and their Children Diagnosed with An Autism Spectrum Disorder Laura Elizabeth Solomon Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the Psychology Commons Repository Citation Solomon, Laura Elizabeth, "Reconstructing Autism: A Phenomenological Study of the Relationship Between Parents and their Children Diagnosed with An Autism Spectrum Disorder" (2011). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 1105. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/1105 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECONSTRUCTING AUTISM: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL STUDY OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PARENTS AND THEIR CHILDREN DIAGNOSED WITH AN AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER PROFESSIONAL DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF PROFESSIONAL PSYCHOLOGY WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY BY LAURA ELIZABETH SOLOMON, Psy.M. IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Dayton, Ohio September, 2012 COMMITTEE CHAIR: Julie L. Williams, Psy.D., CRC, ABPP (RP) Committee Member: Heather N. Wilder, Psy.D. Committee Member: Erendira Lopez-Garcia, Psy.D. WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF PROFESSIONAL PSYCHOLOGY June 2, 2011 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE DISSERTATION PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY LAURA ELIZABETH SOLOMON ENTITLED “RECONSTRUCTING AUTISM: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL STUDY OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PARENTS AND THEIR CHILD DIAGNOSED WITH AN AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER" BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY. -

Biopolitics and Subjectivity: the Case of Autism Spectrum

BIOPOLITICS AND SUBJECTIVITY: THE CASE OF AUTISM SPECTRUM CONDITIONS IN ITALY By M. ARIEL CASCIO Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2015 2 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of M. Ariel Cascio candidate for the degree of Ph.D.*. Committee Chair Atwood D. Gaines Committee Member Eileen Anderson-Fye Committee Member Lee Hoffer Committee Member Anastasia Dimitropoulos Date of Defense March 6, 2015 * We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 3 Table of Contents List of Tables ...................................................................................................................... 7 List of Figures ..................................................................................................................... 8 Preface................................................................................................................................. 9 Acknowledgments............................................................................................................. 11 List of Acronyms .............................................................................................................. 13 Abstract ............................................................................................................................. 11 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... -

Seeking Progressive Fit: a Constructivist Grounded Theory Study

Seeking Progressive Fit: A constructivist grounded theory and autoethnographic study investigating how parents deal with the education of their child with an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) over time Jasmine McDonald BA, DipEd, MSpEd (Hons) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the The University of Western Australia Graduate School of Education 2010 Abstract The aim of the study was to develop substantive theory about how West Australian (WA) parents deal with the education of their child with an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) over time. Estimated prevalence rates for all forms of ASDs worldwide have risen dramatically over the last 50 years. This has meant that there are an ever increasing number of children with an ASD in Australia who need appropriate educational services to maximize their potential. Despite this increase, there have been relatively few studies undertaken which have investigated how parents deal with the education of their child with an ASD over time. There is a call in the research literature to provide different research methodologies to answer alternative questions in regard to education of an individual with an ASD because of the idiosyncratic nature and progress of the disorder. The preferred source of such information is at the local level where individuals with an ASD, parents and professionals who possess the most authentic knowledge can be found. The study was conceptualized within the social theory of symbolic interactionism and used constructivist grounded theory methods and an innovative use of autoethnographic research methods to develop substantive theory about how WA parents deal with the education of their child with an ASD over time. -

Autism Resources

On the Web Local Resources Organizations Inland Empire Autism Society 2276 Griffin Way, Suite 105-194 ASPEN Asperger Syndrome Education Network Corona CA 92879 http://www.aspennj.org/index.asp (Riverside County) Autism Society of America (909) 204-4142 x339 (Main Phone) http://www.autism-society.org Website: www.ieautism.org Autism Speaks™ autism http://www.autismspeaks.org Our Nicholas Foundation Free downloadable 100-Day kit for newly diagnosed families 31493 Rancho Pueblo Road, Suite 205 Resources Temecula, CA 92592 Autism Research Institute http://www.autism.com 951-303-8732 (Office) www.OurNicholasFoundation.org KVCR Autism Initiative & Autism Society – Inland World Autism Empire Chapter http://www.ieautism.org Awareness Day National Autism Association April 2 http://www.nationalautismassociation.org/psa.php International Rett Syndrome Foundation http://www.rettsyndrome.org Informational National Institutes of Health http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/autism/ detail_autism.htm http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/rett/ detail_rett.htm http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/asperger/ asperger.htm Centers for Disease Control and Prevention http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/index.html * Free downloadable fact sheets and parent resource kit Related search terms: Temecula Public Library autism, autistic, autism spectrum, Asperger’s, Asperger Syndrome, PDD-NOS, 30600 Pauba Rd. pervasive developmental disorder, ASD, Temecula, CA 92592 prodigious savant, Rett syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder, sensory 951-693-8900 integration, sensory processing disorder www.temeculalibrary.org Girls Growing Up on the Autism Spectrum: What Parents and Professionals Should Know About the Pre-Teen and Teenage Years Books Author: Shana Nichols / PARENTING 618.92858 NIC Parent Resources Healing and Preventing Autism: A Complete Guide Author: Jenny McCarthy / 618.9285 MCC Helping Children with Autism Learn: Treatment Approaches for Parents and Professionals Author: Bryna Siegel / 371.94 SIE Personal The Autism Encyclopedia Author: John T. -

A Rhetorical Analysis of Three Explanations For

AUTISM AND THE PERPETUAL PUZZLE: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF THREE EXPLANATIONS FOR AUTISM A Dissertation by DENISE MARIE JODLOWSKI Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2009 Major Subject: Communication AUTISM AND THE PERPETUAL PUZZLE: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF THREE EXPLANATIONS FOR AUTISM A Dissertation by DENISE MARIE JODLOWSKI Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Co-Chairs of Committee, James A. Aune Barbara F. Sharf Committee Members, Katherine I. Miller Cynthia Riccio Head of Department, Richard L. Street, Jr. May 2009 Major Subject: Communication iii ABSTRACT Autism and the Perpetual Puzzle: A Rhetorical Analysis of Three Explanations for Autism. (May 2009) Denise Marie Jodlowski, B.A. University of Iowa; M.A., Wake Forest University Co-Chairs of Advisory Committee: Dr. James Arnt Aune Dr. Barbara F. Sharf Autism awareness has increased in recent years in part because it is marked by confusion and controversy. The confusion and controversy stem from the fact that there are many beliefs about autism but little agreement. In this dissertation I examined the rhetoric produced by three primary groups—professional autism experts, caregivers to children with autism and mainstream media. In particular, I studied how each group explains autism. Explanations are vehicles for persuasion; they advance particular viewpoints about an illness. I conducted a rhetorical analysis of the three discourses produced by these groups, highlighting the most cohesive themes to emerge from the discourse. -

A Psycho-Educational Model for the Facilitation of the Mental Health of Families Where a Child Is Diagnosed with Autism

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012) Title of the thesis or dissertation. PhD. (Chemistry)/ M.Sc. (Physics)/ M.A. (Philosophy)/M.Com. (Finance) etc. [Unpublished]: University of Johannesburg. Retrieved from: https://ujdigispace.uj.ac.za (Accessed: Date). A PSYCHO-EDUCATIONAL MODEL FOR THE FACILITATION OF THE MENTAL HEALTH OF FAMILIES WHERE A CHILD IS DIAGNOSED WITH AUTISM By SUMARI BREETZKE Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PhD EDUCATIONIS In PSYCHOLOGY OF EDUCATION In the FACULTY OF EDUCATION At the UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG Supervisor: Professor C.P.H Myburgh Co-supervisor: Professor M. Poggenpoel January 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the following people for contributing towards the completion of my study. Professor Chris Myburgh and Professor Marie Poggenpoel. It is very rare that two people can walk into your life and that you will forever be changed by their presence in your life. Thank you for all that you have done over the years and that you managed to keep me motivated to complete this journey. You will forever have a place in my heart. -

Developing an Understanding of Health Myths and How They Stick and Spread Through the Vaccines Cause Autism

HEALTH MYTHOLOGIES: DEVELOPING AN UNDERSTANDING OF HEALTH MYTHS AND HOW THEY STICK AND SPREAD THROUGH THE VACCINES CAUSE AUTISM MYTH by RICHARD MOCARSKI JASON EDWARD BLACK, COMMITTEE CHAIR MEREDITH BAGLEY ANDREW C. BILLINGS DAVID BIRCH KIMBERLY BISSELL A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication and Information Sciences in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2014 Copyright Richard Anthony Mocarski 2014 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Health myths are health belief systems which prescribe behaviors thought to be health positive by myth-subscribers which are, according to Western medicine, health negative or neutral. These myths become part of individual, family, and community ethnomedical constructions and can have lasting negative health impacts. This project aims to better understand how health myths become lasting and pervasive through a Foucauldian genealogy of the vaccine cause autism (VCA) myth. Using a variety of critical rhetorical lenses—including mythic analysis, the narrative paradigm, circulation theory, performativity, and collective memory—this project analyzes six cases across three realms. In the realm of popular culture Jenny McCarthy’s brand-system and the narratives of autism in TIME and Parenting Magazines are analyzed; in the realm of medicine the diagnostic history of autism in the DSM and foundational articles and the circulation of peer-reviewed scientific articles that arguably link autism to environmental triggers are analyzed; and in the institutional realm Congressional hearings on VCA and the collective memory of autism crafted by non-profits on both side of the VCA debate are analyzed. -

Boys with Autism

101 Tips for The ParenTs of Boys wiTh auTism 101 Tips for The ParenTs of Boys wiTh auTism The Most Crucial Things You Need to Know About Safety, Diagnosis, Doctors, Schooling, Taxes, Vaccinations, Babysitters, Puberty, Self-Care, and More. Ken siri SkyhorSe PubliShing Copyright © 2015 by Ken siri all rights reserved. no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. all inquiries should be addressed to skyhorse Publishing, 307 west 36th street, 11th floor, new york, ny 10018. skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. special editions can also be created to specifications. for details, contact the special sales Department, skyhorse Publishing, 307 west 36th street, 11th floor, new york, ny 10018 or [email protected]. skyhorse® and skyhorse Publishing® are registered trademarks of skyhorse Publishing, inc.®, a Delaware corporation. Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file. isBn: 978-1-62914-507-5 ebook isBn: 978-1-62914-841-0 Printed in the united states of america WARNING: The information contained herein is for informational purposes only. neither the editor, nor the publisher, nor any other person or entity can take any medical or legal responsibility of having the information contained within 101 Tips for the Parents of Boys with Autism considered as a prescription for any person. -

Lending Library

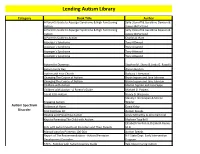

Lending Autism Library Category Book Title Author A Parent's Guide to Asperger Syndrome & High Functioning Sally Ozonoff & Geraldine Dawson & Autism James McPartland A Parent's Guide to Asperger Syndrome & High Functioning Sally Ozonoff & Geraldine Dawson & Autism James McPartland A Parent's Guide to Autism Charles A. Hart Asperger's Syndrome Tony Attwood Asperger's Syndrome Tony Attwood Asperger's Syndrome Tony Attwood Asperger's Syndrome Tony Attwood Autism for Dummies Stephen M. Shore & Linda G. Rastelli Autism Every Day Alyson Beytien Autism and Your Church Barbara J. Newman Changing The Course of Autism Bryan Jepson and Jane Johnson Changing The Course of Autism Bryan Jepson and Jane Johnson Children with Autism Marian Sigman and Lisa Capps Children with Autism - A Parent's Guide Michael D. Powers Could It Be Autism Nancy D. Wiseman Stanley I. Greenspan & Serena Engaging Autism Wieder Autism Spectrum Evidence of Harm David Kirby Disorder First 100 Days Kit Autism Speaks Healing and Preventing Autism Jenny McCarthy & Jerry Kartzinel Keys to Parenting The Child with Autism Marlene Targ Brill Elizabeth Verdick & Elizabeth Reeve, Kids with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Their Parents M.D Manual para los Primeros 100 Días Autism Speaks Report of The Recommendations - Autism/Pervasive N.Y State Dept. Early Intervention Development Disorders Program TACA - Families with Autism Journey Guide Talk About Curing Autism Autism Spectrum Disorder Lending Autism Library Category Book Title Author TACA - Families with Autism Journey Guide -Early -

Title Subtitle Author Category C. R. Date Building a Home

Title Subtitle Author Category C. R. Date Meeting the emotional needs of children and youth in foster Heineman and Building a Home Within care Ehrensaft ACEs and Trauma 2006 How your biography becomes yourbiology and how you can Childhood Disrupted heal Jackson‐ Nakazawa ACEs and Trauma 2016 A manual for child‐parent psychotherapy with young Lieberman Don't Hit My Mommy witnesses of family violence andVanHorn ACEs and Trauma 2005 Acaregivers guide to helping young children affected by Fitzgerald‐ Rice and Hope and Healing trauma McAlister‐Groves ACEs and Trauma 2005 Embracing dark emotions through integrative mindful exposure: A User's guide to How to Lose Control and Gain Emotional Freedom Psychotherapy and life Duvinsky ACEs and Trauma 2012 Guidelines for the treatment of Lieberman; Compton; traumatic bereavement in VanHorn and Ghosh Losing a Parent to Death in the Early Years infancy and early childhood Ippen ACEs and Trauma 2003 Reclaiming childhood in a Their Name is Today hostile world Shriver ACEs and Trauma 2014 The impact of childhood abuse ACEs and Trauma/ Parenting with PTSD on parenting Daum and Brandt Caregiving 2017 A Curriculum to foster strength, ACEs and Trauma/ Raising Resilient Children hope, and optimism in children Goldstein and Brooks Caregiving 2004 Childhood abuse survivors ACEs and Trauma/ Trigger Points experiences of parenting Daum and Brandt Caregiving 2015 Simple Strategies to Succeed in ADHD/ Executive ** Organizing the Disorganized Child School Kutscher and Moran Functioning 2009 Citizen Advocacy for People