The Liberal Party of Australia's Campaign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Procedural Digest 24 25 26 27 28

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES August/ September 2020 M T W T F Procedural Digest 24 25 26 27 28 No. 12 31 1 2 3 4 46th Parliament 24 August – 3 September 2020 Selected entries contain links to video footage via Parlview. Please note that the first time you click a [Watch] link, you may need to refresh the page (ctrl+F5) for the correct starting point. Bills 12.01 Jobkeeper bill introduced and passed all stages in one sitting The Treasurer presented the Coronavirus Economic Response Package (Jobkeeper Payments) Amendment Bill 2020 on 26 August. In his second reading speech, the Treasurer thanked the opposition for its support in progressing the bill through the parliament quickly to provide certainty to Australian businesses and employees. Following his speech, the House gave leave for the debate to be made an order of the day for a later hour. During the day, 28 members contributed to the second reading debate. At the conclusion of the debate, a second reading amendment moved by the shadow Treasurer was negatived on division and the question ‘that the bill be read a second time’ was carried on the voices. Following a message from the Governor-General recommending appropriation, the bill proceeded to the consideration in detail stage and several opposition amendments were negatived on division. Consideration in detail concluded and, by leave, an assistant minister moved the third reading. The question ‘that the bill be read a third time’ was carried on the voices. The Speaker granted the Manager of Opposition Business indulgence a number of times over the sitting fortnight to place on the record the voting intentions of independent and minor party members unable to attend the sittings due to the pandemic. -

QLD Senate Results Report 2017

Statement of Results Report Event: 2016 Federal Election - Full Senate Ballot: 2016 Federal Election - Full Senate Order Elected Candidates Elected Group Name 1 George BRANDIS Liberal National Party of Queensland 2 Murray WATT Australian Labor Party 3 Pauline HANSON Pauline Hanson's One Nation 4 Matthew CANAVAN Liberal National Party of Queensland 5 Anthony CHISHOLM Australian Labor Party 6 James McGRATH Liberal National Party of Queensland 7 Claire MOORE Australian Labor Party 8 Ian MACDONALD Liberal National Party of Queensland 9 Andrew BARTLETT The Greens 10 Barry O'SULLIVAN Liberal National Party of Queensland 11 Chris KETTER Australian Labor Party 12 Fraser ANNING Pauline Hanson's One Nation Senate 06 Nov 2017 11:50:21 Page 1 of 5 Statement of Results Report Event: 2016 Federal Election - Full Senate Ballot: 2016 Federal Election - Full Senate Order Excluded Candidates Excluded Group Name 1 Single Exclusion Craig GUNNIS Palmer United Party 2 Single Exclusion Ian EUGARDE 3 Single Exclusion Ludy Charles SWEERIS-SIGRIST Christian Democratic Party (Fred Nile Group) 4 Single Exclusion Terry JORGENSEN 5 Single Exclusion Reece FLOWERS VOTEFLUX.ORG | Upgrade Democracy! 6 Single Exclusion Gary James PEAD 7 Single Exclusion Stephen HARDING Citizens Electoral Council 8 Single Exclusion Erin COOKE Socialist Equality Party 9 Single Exclusion Neroli MOONEY Rise Up Australia Party 10 Single Exclusion David BUNDY 11 Single Exclusion John GIBSON 12 Single Exclusion Chelle DOBSON Australian Liberty Alliance 13 Single Exclusion Annette LOURIGAN Glenn -

A History of Misconduct: the Case for a Federal Icac

MISCONDUCT IN POLITICS A HISTORY OF MISCONDUCT: THE CASE FOR A FEDERAL ICAC INDEPENDENT JO URNALISTS MICH AEL WES T A ND CALLUM F OOTE, COMMISSIONED B Y G ETUP 1 MISCONDUCT IN POLITICS MISCONDUCT IN RESOURCES, WATER AND LAND MANAGEMENT Page 5 MISCONDUCT RELATED TO UNDISCLOSED CONFLICTS OF INTEREST Page 8 POTENTIAL MISCONDUCT IN LOBBYING MISCONDUCT ACTIVITIES RELATED TO Page 11 INAPPROPRIATE USE OF TRANSPORT Page 13 POLITICAL DONATION SCANDALS Page 14 FOREIGN INFLUENCE ON THE POLITICAL PROCESS Page 16 ALLEGEDLY FRAUDULENT PRACTICES Page 17 CURRENT CORRUPTION WATCHDOG PROPOSALS Page 20 2 MISCONDUCT IN POLITICS FOREWORD: Trust in government has never been so low. This crisis in public confidence is driven by the widespread perception that politics is corrupt and politicians and public servants have failed to be held accountable. This report identifies the political scandals of the and other misuse of public money involving last six years and the failure of our elected leaders government grants. At the direction of a minister, to properly investigate this misconduct. public money was targeted at voters in marginal electorates just before a Federal Election, In 1984, customs officers discovered a teddy bear potentially affecting the course of government in in the luggage of Federal Government minister Australia. Mick Young and his wife. It had not been declared on the Minister’s customs declaration. Young This cheating on an industrial scale reflects a stepped aside as a minister while an investigation political culture which is evolving dangerously. into the “Paddington Bear Affair” took place. The weapons of the state are deployed against journalists reporting on politics, and whistleblowers That was during the prime ministership of Bob in the public service - while at the same time we Hawke. -

The Tocsin | Issue 12, 2021

Contents The Tocsin | Issue 12, 2021 Editorial – Shireen Morris and Nick Dyrenfurth | 3 Deborah O’Neill – The American Warning | 4 Kimberley Kitching – Super Challenges | 7 Kristina Keneally – Words left unspoken | 10 Julia Fox – ‘Gender equality is important but …’ | 12 In case you missed it ... | 14 Clare O’Neil – Digital Dystopia? | 16 Amanda Rishworth – Childcare is the mother and father of future productivity gains | 18 Shireen Morris – Technology, Inequality and Democratic Decline | 20 Robynne Murphy – How women took on a giant and won | 24 Shannon Threlfall-Clarke – Front of mind | 26 The Tocsin, Flagship Publication of the John Curtin Research Centre. Issue 12, 2021. Copyright © 2021 All rights reserved. Editor: Nick Dyrenfurth | [email protected] www.curtinrc.org www.facebook.com/curtinrc/ twitter.com/curtin_rc Editorial Executive Director, Dr Nick Dyrenfurth Committee of Management member, Dr Shireen Morris It was the late, trailblazing former Labor MP and Cabinet Minister, Susan Ryan, who coined the memorable slogan ‘A must be identified and addressed proactively. We need more Woman’s Place is in the Senate’. In 1983, Ryan along with talented female candidates being preselected in winnable seats. Ros Kelly were among just four Labor women in the House of We need more female brains leading in policy development Representatives, together with Joan Child and Elaine Darling. and party reform, beyond the prominent voices on the front As the ABC notes, federal Labor boasts more than double the bench. We need to nurture new female talent, particularly number of women in Parliament and about twice the number women from working-class and migrants backgrounds. -

An Analysis of the Loss of HMAS SYDNEY

An analysis of the loss of HMAS SYDNEY By David Kennedy The 6,830-ton modified Leander class cruiser HMAS SYDNEY THE MAIN STORY The sinking of cruiser HMAS SYDNEY by disguised German raider KORMORAN, and the delayed search for all 645 crew who perished 70 years ago, can be attributed directly to the personal control by British wartime leader Winston Churchill of top-secret Enigma intelligence decodes and his individual power. As First Lord of the Admiralty, then Prime Minster, Churchill had been denying top secret intelligence information to commanders at sea, and excluding Australian prime ministers from knowledge of Ultra decodes of German Enigma signals long before SYDNEY II was sunk by KORMORAN, disguised as the Dutch STRAAT MALAKKA, off north-Western Australia on November 19, 1941. Ongoing research also reveals that a wide, hands-on, operation led secretly from London in late 1941, accounted for the ignorance, confusion, slow reactions in Australia and a delayed search for survivors . in stark contrast to Churchill's direct part in the destruction by SYDNEY I of the German cruiser EMDEN 25 years before. Churchill was at the helm of one of his special operations, to sweep from the oceans disguised German raiders, their supply ships, and also blockade runners bound for Germany from Japan, when SYDNEY II was lost only 19 days before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and Southeast Asia. Covering up of a blunder, or a punitive example to the new and distrusted Labor government of John Curtin gone terribly wrong because of a covert German weapon, can explain stern and brief official statements at the time and whitewashes now, with Germany and Japan solidly within Western alliances. -

Australian Institute of International Affairs National Conference

Australian Institute of International Affairs National Conference Australian Foreign Policy: Navigating the New International Disorder Monday 21 November 2016 Hotel Realm Canberra, National Circuit, Barton Arrival 8:30 – 9:00am Australian Foreign Policy 9:00am – 11:00am The Hon Julie Bishop MP (Invited) Minister for Foreign Affairs Julie Bishop is the Minister for Foreign Affairs in Australia's Federal Coalition Government. She is also the Deputy Leader of the Liberal Party and has served as the Member for Curtin since 1998. Minister Bishop was sworn in as Australia's first female Foreign Minister on 18 September 2013 following four years in the role of Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade. She previously served as a Cabinet Minister in the Howard Government as Minister for Education, Science and Training and as the Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Women's Issues. Prior to this, Minister Bishop was Minister for Ageing. Minister Bishop has also served on a number of parliamentary and policy committees including as Chair of the Joint Standing Committee on Treaties. Before entering Parliament Minister Bishop was a commercial litigation lawyer at Perth firm Clayton Utz, becoming a partner in 1985, and managing partner in 1994. The Hon Kim Beazley AC FAIIA AIIA National President Mr Beazley was elected to the Federal Parliament in 1980 and represented the electorates of Swan (1980-96) and Brand (1996- 2007). Mr Beazley was a Minister in the Hawke and Keating Labor Governments (1983-96) holding, at various times, the portfolios of Defence, Finance, Transport and Communications, Employment Education and Training, Aviation, and Special Minister of State. -

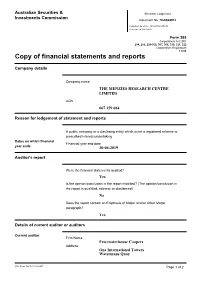

Copy of Financial Statements and Reports

Australian Securities & Electronic Lodgement Investments Commission Document No. 7EAQ24912 Lodgement date/time: 14-10-2019 14:04:53 Reference Id: 131203477 Form 388 Corporations Act 2001 294, 295, 298-300, 307, 308, 319, 321, 322 Corporations Regulations 1.0.08 Copy of financial statements and reports Company details Company name THE MENZIES RESEARCH CENTRE LIMITED ACN 067 359 684 Reason for lodgement of statement and reports A public company or a disclosing entity which is not a registered scheme or prescribed interest undertaking Dates on which financial Financial year end date year ends 30-06-2019 Auditor's report Were the financial statements audited? Yes Is the opinion/conclusion in the report modified? (The opinion/conclusion in the report is qualified, adverse or disclaimed) No Does the report contain an Emphasis of Matter and/or Other Matter paragraph? Yes Details of current auditor or auditors Current auditor Firm Name Pricewaterhouse Coopers Address One International Towers Watermans Quay ASIC Form 388 Ref 131203477 Page 1 of 2 Form 388 - Copy of financial statements and reports THE MENZIES RESEARCH CENTRE LIMITED ACN 067 359 684 Barangaroo Sydney 2001 Australia Certification I certify that the attached documents are a true copy of the original reports required to be lodged under section 319 of the Corporations Act 2001. Yes Signature Select the capacity in which you are lodging the form Secretary I certify that the information in this form is true and complete and that I am lodging these reports as, or on behalf of, the company. -

Liberal Women: a Proud History

<insert section here> | 1 foreword The Liberal Party of Australia is the party of opportunity and choice for all Australians. From its inception in 1944, the Liberal Party has had a proud LIBERAL history of advancing opportunities for Australian women. It has done so from a strong philosophical tradition of respect for competence and WOMEN contribution, regardless of gender, religion or ethnicity. A PROUD HISTORY OF FIRSTS While other political parties have represented specific interests within the Australian community such as the trade union or environmental movements, the Liberal Party has always proudly demonstrated a broad and inclusive membership that has better understood the aspirations of contents all Australians and not least Australian women. The Liberal Party also has a long history of pre-selecting and Foreword by the Hon Kelly O’Dwyer MP ... 3 supporting women to serve in Parliament. Dame Enid Lyons, the first female member of the House of Representatives, a member of the Liberal Women: A Proud History ... 4 United Australia Party and then the Liberal Party, served Australia with exceptional competence during the Menzies years. She demonstrated The Early Liberal Movement ... 6 the passion, capability and drive that are characteristic of the strong The Liberal Party of Australia: Beginnings to 1996 ... 8 Liberal women who have helped shape our nation. Key Policy Achievements ... 10 As one of the many female Liberal parliamentarians, and one of the A Proud History of Firsts ... 11 thousands of female Liberal Party members across Australia, I am truly proud of our party’s history. I am proud to be a member of a party with a The Howard Years .. -

First Century Fox Inc and Sky Plc; European Intervention Notice

Rt Hon Karen Bradley Secretary of State for Digital Culture Media and Sport July 14 2017 Dear Secretary of State Twenty-First Century Fox Inc and Sky plc; European Intervention Notice The Campaign for Press and Broadcasting is responding to your request for new submissions on the test of commitment to broadcasting standards. We are pleased to submit this short supplement to the submission we provided for Ofcom in March. As requested, the information is up-to-date, but we are adding an appeal to you to reconsider Ofcom’s recommendation to accept the 21CF bid on this ground, which we find wholly unconvincing in the light of the evidence we submitted. SKY NEWS IN AUSTRALIA In a pre-echo of the current buyout bid in the UK, Sky News Australia, previously jointly- owned with other media owners, became wholly owned by the Murdochs on December 1 last year. When the CPBF made its submission on the Commitment to Broadcasting Standards EIN to Ofcom in March there were three months of operation by which to judge the direction of the channel, but now there are three months more. A number of commentaries have been published. The Murdoch entity that controls Sky Australia is News Corporation rather than 21FC but the service is clearly following the Fox formula about which the CPBF commented to Ofcom. Indeed it is taking the model of broadcasting high-octane right-wing political commentary in peak viewing times even further. While Fox News has three continuous hours of talk shows on weekday evenings, Sky News Australia has five. -

P5048b-5048B Hon Darren West

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Wednesday, 22 August 2018] p5048b-5048b Hon Darren West FEDERAL COALITION GOVERNMENT Statement HON DARREN WEST (Agricultural — Parliamentary Secretary) [6.46 pm]: I note that other members also wish to make a member’s statement, so I will be brief. Hon Simon O’Brien has given me a couple of good segues for my statement tonight. I believe that there will be a special meeting, and votes will be counted, and at the end of that we could have a new Prime Minister of Australia. This has been an extraordinary week in Canberra. For those of us who take a particular interest in political happenings in our national capital, I guess we could say we have seen it all before. However, this time I think there is an extra level of division and dysfunction than what we have seen in governments previous. It is extraordinary that there is potential for a second leadership spill in two days in the Liberal Party in Canberra to determine who will be this country’s next Prime Minister. This seems to be spreading from the Western Australian branch of the Liberal Party, although there is not a formal coalition in Western Australia, to its federal counterparts. It is extraordinary. I believe there will be a leadership spill in Canberra. There probably should also be a leadership spill in Western Australia, if anyone had the courage to challenge the current Leader of the Liberal Party. I am sure that will happen in due course, members. There is also potential for a change of leadership in the federal National Party in the coming days as the dysfunction spreads throughout the federal government. -

Ministerial Staff Under the Howard Government: Problem, Solution Or Black Hole?

Ministerial Staff Under the Howard Government: Problem, Solution or Black Hole? Author Tiernan, Anne-Maree Published 2005 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Department of Politics and Public Policy DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3587 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367746 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Ministerial Staff under the Howard Government: Problem, Solution or Black Hole? Anne-Maree Tiernan BA (Australian National University) BComm (Hons) (Griffith University) Department of Politics and Public Policy, Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2004 Abstract This thesis traces the development of the ministerial staffing system in Australian Commonwealth government from 1972 to the present. It explores four aspects of its contemporary operations that are potentially problematic. These are: the accountability of ministerial staff, their conduct and behaviour, the adequacy of current arrangements for managing and controlling the staff, and their fit within a Westminster-style political system. In the thirty years since its formal introduction by the Whitlam government, the ministerial staffing system has evolved to become a powerful new political institution within the Australian core executive. Its growing importance is reflected in the significant growth in ministerial staff numbers, in their increasing seniority and status, and in the progressive expansion of their role and influence. There is now broad acceptance that ministerial staff play necessary and legitimate roles, assisting overloaded ministers to cope with the unrelenting demands of their jobs. However, recent controversies involving ministerial staff indicate that concerns persist about their accountability, about their role and conduct, and about their impact on the system of advice and support to ministers and prime ministers. -

Inaugural Speech of the Honourable David Clarke

INAUGURAL SPEECH OF THE HONOURABLE DAVID CLARKE The Hon. DAVID CLARKE [8.11 p.m.] (Inaugural speech): I also oppose this legislation. In speaking for the first time I do so with a great and abiding recognition of the responsibilities that my new office places upon me and with the hope that my time spent here will be productive in service to the people of New South Wales. I come to this House as one who by conviction and belief respects, supports and upholds its history and traditions. As a member of the Legislative Council I will resist with all the vigour I can any and all attempts to bring about this House's demise, to weaken its powers or to diminish its stature and traditions in any way. Over the years many outstanding and distinguished members have served in this Chamber. The late Jim Cameron was a member whose values and social beliefs I identify with. He had a unique and inspirational capacity to espouse values in noble and uplifting language as befits such noble values. A former and distinguished President of the House, Johno Johnson, representing an historic political institution of our country, the Australian Labor Party, has also been courageous, forthright and determined, especially in his elevation of the family, his defence of the right to life of the unborn child and his denunciation of abortion. He continues to champion these causes outside this Chamber. I deem it an honour to find myself serving in this House at the same time as Deputy-President Reverend the Hon.