Dead but Not Forgotten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Rights Review 2016

HUMAN RIGHTS REVIEW 2016 I Insha Malik, 14, blinded in both her eyes due to pellets fired at her by government forces Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society The Bund, Amira Kadal, Srinagar J&K www.jkccs.net PAGE 1 BRIEF OVERVIEW OF YEAR 2016 The year of 2016 has just ended. The year of 2016 has singularly been one of the most violent years of the last decade. The scale of human rights violence perpetrated against the people of Jammu and Kashmir alone suggests that the governments in Kashmir continue to repress the political aspirations of people with absolute and total violence. The year of 2016 has not just seen the killing of almost 145 civilians at the hands of police and paramilitary personal, but it has seen an upward trend in the number of militants and armed forces killings. The year of 2016 was marred with an unprecedented cycle of violence. Throughout the year Kashmiris witnessed gross violations of human rights in the form of extrajudicial executions, injuries, illegal detentions, torture, sexual violence, disappearances, arson and vandalism of civilian properties, restriction on congregational religious activities, media gags, and ban on communication and internet services, etc. The most fundamental rights of people were curtailed through the imposition of curfew, strikes and continued violence. The long pending conflict in Jammu and Kashmir continues to take human lives every year, endlessly. In 2016 the Jammu and Kashmir witnessed the killing of 383 persons which is statistically the highest in last five years. Moreover, thousands and thousands of persons were injured and there were illegal detentions of around 10,000 people besides arson and clampdown of communication services. -

Page1.Qxd (Page 3)

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 27, 2018 (PAGE 6) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU From page 1 DB issues notice to Chairman, others J&K’s Anti-Corruption Bureau 58 Forest officers shifted 3 CEs given addl charge, 2 X-Ens shifted Sudheer Kumar Shah, I/C General Manager , JKPCC months was repeatedly objected “Though the Forensic Shweta Jandial I/C Jt DFO Demarcation Div-I Jammu Chief Engineer PW(R&B) Kashmir has been shifted and becomes operational from today Director Soil Conservation vice Sanjay Kumar Gupta who to by the Members of the Science Laboratory has twice Department Jammu shall also placed as I/C Executive “The rules governing the Station of Jammu will have Jammu has been posted as DFO has been now placed as DFO SF Commission especially when established forgery of policy hold the additional charge of the Engineer in J&K State manpower at the disposal of jurisdiction over Jammu- Udhampur vice Naresh Majotra Jammu; Neha Mehta DFO SF they found clear mismatch documents-vis-à-vis engage- post of Chief Engineer Vigilance Organisation, Anti-Corruption Bureau will Samba-Kathua districts while as who has now been placed as Jammu has been placed as DFO between marks in written exam- ment and continuance of SKUAST-Jammu till further Srinagar, Vijay Kumar Gupta be the same which are present- the Police Station of Srinagar Principal, Forest Guard Training Research SFRI, Jammu; Ayub ination and viva-voce of some Consultants yet the Crime orders while Abdul Majid I/C XEn awaiting orders of post- ly in vogue for the State will have jurisdiction over School Doomi ,Akhnoor. -

Aadhaar Enrolment Enabled Business Units

S.No Center Location 1 J&K Bank BU:Shalamar Road Block:Jammu ,district:Jammu 2 J&K Bank BU:Gandhi Nagar Block:Jammu ,district:Jammu 3 J&K Bank BU:Patel Nagar Block:Jammu ,district:Jammu 4 J&K Bank BU:Channi Himmat Block:Jammu ,district:Jammu 5 J&K Bank BU:Akhnoor Block:Akhnoor,district:Jammu 6 J&K Bank BU:Durga Nagar Block:jammu,district:Jammu 7 J&K Bank BU:Sidhra Block:Dansal ,district:Jammu 8 J&K Bank BU:Nagrota Block:Dansal ,district:Jammu 9 J&K Bank BU:Arnia Block:Bishnah,district:Jammu 10 J&K Bank BU:Khour Block:Khour,district:Jammu 11 J&K Bank BU:Bari brahamna Block:Bari Brahmna ,district:Samba 12 J&K Bank BU:Samba main Block:Samba ,district:Samba 13 J&K Bank BU:Dayalachak Block:Hiranagar,district:KATHUA 14 J&K Bank BU:Phinter Block:Bilawar,district:KATHUA 15 J&K Bank BU:Basoli Block:Basholi,district:KATHUA 16 J&K Bank BU:Kalibari Block:Hiranagar,district:KATHUA 17 J&K Bank BU:Doda Main Block:Doda ,district:Doda 18 J&K Bank BU: Seri Block:Thatri ,district:Doda 19 J&K Bank BU:Hidyal Block:Kishtwar ,district:Doda 20 J&K Bank BU:Kuleed Block:Kishtwar ,district:Doda 21 J&K Bank BU: Tethar Block:Banihal ,district:Doda 22 J&K Bank BU: Maitra Ramban Block:Ramban ,district:Ramban 23 J&K Bank BU: Cama Housing Colony Udhampur, Block:Udhampur ,district:Udhampur 24 J&K Bank BU:SMM Ramnagar,Udhampur Block:Udhampur ,district:Udhampur 25 J&K Bank BU: Rehambal, Udhampur Block:Udhampur,district:Udhampur 26 J&K Bank BU: Arli Katra, Reasi Block:Katra ,district:Reasi 27 J&K Bank BU: DC Office Reasi Block:Reasi ,district:Reasi 28 J&K Bank BU: Kheora -

Fresh Spurt in COVID Cases As 708 Test Positive In

9thyear of publication SRINAGAR OBSERVER J&K ERA Starts Work On Rs 9.67 Crore Ensure hassle free services to the people “Commissioner SMC directs Advisor Khan Inspects Progress Of “Rigid Concrete Pavement” Works Of Sports Facilities At Srinagar Jammu and Kashmir Economic Reconstruction Agency Commissioner Srinagar Municipal Corporation Mr Gazanfar Ali today today started work on Rs 9.16 crore “Rigid Concrete reviewed Mohharam UL Haram arrangements in Shia populated areas Advisor to Lieutenant Governor, Farooq Khan took stock of Pavement “of Civil –Secretariat to Rambagh Chowk at Shalimar , Chandpora, Harwan , Lashkare Mohhalla , Hasnabad and progress of sports infrastructure development works at road. The work on the sub-project being executed under several other adjoining Areas. Mr Ali who visited these | Page 03 Multipurpose Indoor Sports Hall Polo Ground and Water Sports World Bank funded JTFRP (Jhelum Tawi Flood | Page 07 Center Nehru Park here today. During his visit to | Page 05 THURSDAY, AUGUST 20, 2020 29, Zil Hajj 1441 Hijri Published from Srinagar RNI No:JKENG/2012/43267 Vol:9 Issue No: 190 Pages:8 Rs.5.00 epaper: www.srinagarobserver.com BRIEFNEWS 3 Militants Labourer drowns to Fresh Spurt in COVID Cases death in Pulwama Killed in Twin PULWAMA: A 20-year-old labourer was on Wednesday drowned to death while extracting sand from river As 708 Test Positive In J&K Kashmir Gunfights Jhelum in South Kashmir district of Pulwama. An official told a local news Jehangeer Ganai gathering agency that a group of men 15 More Die of were extracting sand from Jhelum in boats at Karnabal Kakapora area of SRINAGAR: Jammu and COVID in Valley, Pulwama on Wednesday. -

20 Hizb Commander Junaid Sehrai Killed in Srinagar Encounter

LAST PAGE...P.8 WEDNESDAY C MAY-2020 KASHMIR M 23 Y SRINAGAR TODAY : SUNNY Contact 20 K : -0194-2502327 FOR SUBSCRIPTIONS & YOUR COPY OF Maximum : 25°c SUNSET Today 07:29 PM Minmum : 11°c SUNRISE Humidity : 49% Tommrow 05:26 AM 26 Ramazan-ul-Mubarak | 1441 Hijri | Vol: 23 | Issue: 107 | Pages: 08 | Price: `3 www.kashmirobserver.net twitter.com / kashmirobserver facebook.com/kashmirobserver Postal Regn: L/159/KO/SK/2014-2016 hen spouses, who are co-parenting, are together, they show higher similarities in brain responses to the infant .....LIFE & TIMES PRESENCE OF SPOUSES WHO ARE stimuli than when they are separated, suggests a novel study. The study led by researchers at the Nanyang WTechnological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore), was published in the journal Scientific Reports. CO-PARENTING CAN ALTER EACH The researchers analysed how the brain activity of 24 pairs of husband and wife from Singapore changed in response P6 OTHER'S BRAIN ACTIVITY: STUDY to recordings of infant stimuli such as crying, when they were physically together and when they were separated. This effect was only found in true couples and not in randomly matched study participants..... News Digest J&K Govt Issues Fresh List Of 26TH RAMAZAN Hizb Commander IFTAR SEHRI Red, Orange; Green Districts TODAY TOMMOROW FIQAH Except Ganderbal, Bandipora; All Kashmir Districts Red Zones HANAFIYA 07:32 03:48 FIQAH Junaid Sehrai Killed Observer News Service and Bandipora are listed JAFARIYA 07:41 03:46 as Red zones, while as JAMMU- The Jammu and Kathua, Samba and Ram- RED Kashmir Government ban districts of Jammu ANANTNAG today issued the fresh Province have been de- In Srinagar Encounter BARAMULLA classification of districts clared Red zones. -

Brief Industrial Profile of Baramulla District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Baramulla District Carried out by MSME-Development Institute, J&K-JAMMU (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) Phone Phone0191-2431077, 2435425 Fax: 0191-2431077,2435425 e-mail: [email protected] Web- www.msmedijammu.gov. Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 1 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 1 1.2 Topography 2 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 2 1.4 Forest 3 1.5 Administrative set up 3 2. District at a glance 4-6 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in the District 7 3. Industrial Scenario 8 3.1 Industry at a Glance 8 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 8 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units In The 9 District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 10 3.5 Major Exportable Item 3.6 Growth Trend 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 3.8.1 List of the units in ------ & near by Area 3.8.2 Major Exportable Item 3.9 Service Enterprises 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 10 5. General issues raised by industry association during the course of 11 meeting 6 Steps to set up MSMEs 12 1 Brief Industrial Profile Baramulla District 1. General Characteristics of the District The city of Baramulla, founded by Raja Bhimsina held the position of a gate-way to the valley as it was located on the route to the Valley from Muzaffarabad, now in POK, and Rawalpindi, now in Pakistan. -

Afghan Rule in Kashmir (A Critical Review of Source Material)

Afghan Rule in Kashmir (A Critical Review of Source Material) Dissertation submitted to the University of Kashmir for the Award of the Degree of Master of Philosophy (M. Phil) In Department of History By Rouf Ahmad Mir Under the Supervision of Dr. Farooq Fayaz (Associate Professor) Post Graduate Department of History University Of Kashmir Hazratbal, Srinagar-6 2011 Post Graduate Department of History University of KashmirSrinagar-190006 (NAAC Accredited Grade “A”) CERTIFICATE This is to acknowledge that this dissertation, entitled Afghan Rule in Kashmir: A Critical Review of Source Material, is an original work by Rouf Ahmad, Scholar, Department of History, University of Kashmir, under my supervision, for the award of Pre-Doctoral Degree (M.Phil). He has fulfilled the entire statutory requirement for submission of the dissertation. Dr. Farooq Fayaz (Supervisor) Associate Professor Post Graduate Department of History University of Kashmir Srinagar-190006 Acknowledgement I am thankful to almighty Allah, our lord, Cherisher and sustainer. At the completion of this academic venture, it is my pleasure that I have an opportunity to express my gratitude to all those who have helped and encouraged me all the way. I express my gratitude and reverence to my teacher and guide Dr. Farooq Fayaz Associate Professor, Department of History University of Kashmir, for his generosity, supervision and constant guidance throughout the course of this study. It is with deep sense of gratitude and respect that I express my thanks to Prof. G. R. Jan (Professor of Persian) Central Asian Studies, University of Kashmir, my co-guide for his unique and inspiring guidance. -

Jammu and Kashmir

STATE REVIEWS Indian Minerals Yearbook 2017 (Part- I) 56th Edition STATE REVIEWS (Jammu & Kashmir) (FINAL RELEASE) GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF MINES INDIAN BUREAU OF MINES Indira Bhavan, Civil Lines, NAGPUR – 440 001 PHONE/FAX NO. (0712) 2565471 PBX : (0712) 2562649, 2560544, 2560648 E-MAIL : [email protected] Website: www.ibm.gov.in March, 2018 11-1 STATE REVIEWS JAMMU & KASHMIR Production Coal and limestone are the important miner- Mineral Resources als produced in Jammu & Kashmir state. Jammu & Kashmir is the sole holder of The value of minor minerals’ production was country's borax, sapphire, and sulphur (native) estimated at ` 213 crore for the year 2016-17 resources and possesses 33% graphite, 23% (Table-4). marble and 14% of gypsum. Coal, gypsum and There were 5 reporting mines in 2016-17 for limestone are the important minerals produced in the mineral limestone. the State. Coal occurs in Kupwara districts; Mineral-based Industry gypsum in Baramulla & Doda districts; limestone Jammu & Kashmir Cements Ltd, a State in Anantnag, Baramulla, Kathua, Leh, Poonch, Pulwama, Rajauri, Srinagar & Udhampur districts; Government Undertaking, operates a cement plant and magnesite in Leh & Udhampur districts. of 1.98 lakh tpy capacity at Khrew in Pulwama Other minerals that occur in the State are district. The company also owns a small cement bauxite & china clay in Udhampur district; plant of 20,000 tpy capacity located at Wuyan in bentonite in Jammu district; borax & sulphur in Srinagar district, besides two other tiny cement Leh district; diaspore in Rajouri & Udhampur plants that have a total capacity of 39,000 tpy. -

Technological Evolution Devolves 'Typewritter's Life'

Vol 10●No 16●Pages 16●September 15, 2017 ﻮر य ﯽ اﻟﻨ गम ﻟ ोत ﺖ ا ﻤ ٰ ा ﻠ ﻈ म ﻟ ो ا ﻦ स ﻣ म त U N IR IV M ER H SITY OF KAS MERCMEDIA EDUCATION TIMES RESEARCH CENTRE, UNIVERSITY OF KASHMIR TECHNOLOGICAL EVOLUTION DEVOLVES ‘TYPEWRITTER’S LIFE’ Kashmir University Media Students 2 teachers for Food on the go release heart-throbbing short film 85 students P11 P8 P9 ﻮر य ﯽ اﻟﻨ गम ﻟ ोत ﺖ ا ﻤ ٰ ा ﻠ MEDIA EDUCATION RESEARCH CENTRE, UNIVERSITY OF KASHMIR ﻈ म ﻟ ो ا ﻦ स ﻣ म त U R NI I VE HM RSI AS Vol 10●No 16●Pages 16●September 15, 2017 TY OF K 2 TEENAGERS TURN INTO Poor infrastructure haunts athletes ENTREPRENEUR v Mehwish Mumtaz Budgam: Bakshi Stadium, one of the oldest stadium of the valley, where every now and then, hosts of activities are being organized by spectrum of sports bodies and till date the authorities managing it have not undertaken any initiative to renovate the filthiest toilet where sewage overflows in the bathroom area and v Musaib Mehraj stench haunts the budding athletes. Apart, from unhygienic toilet, the young sports men or women Srinagar: Three teenagers have set an example have no changing rooms. by launching their own firm to turn their passion for The stadium which was constructed in 1960 software development into a working business model. continues with the same outlook and in fact Basar Qari from Bagh-e-Mehtab area of Srinagar joined has gone from bad to worse as evident from the hands with two of his close friends, Zuhaib Zahoor and condition of the stands or ground. -

I-AREA and POPULATION Table No

1 DIGEST OF STATISTICS 2013-14 I-AREA AND POPULATION Table No. 1.00 (Cntd.) Jammu and Kashmir State at a Glance - 2011 Census i. Area in Sq. Kms. 222236* ii. No. of Districts 22 iii. No. of Tehsils 82 iv. No. of CD Blocks (-) 143 v. No. of Panchayats (-) 4128 vi. No. of Villages 6671 vii. No. of Towns 86 1. Population-2011 Persons Males Females Total 12541302 6640662 5900640 Rural 9108060 4774477 4333583 Urban 3433242 1866185 1567057 2. Population Growth 2001-2011 Absolute Total 2397602 1279736 1117866 Rural 1480998 796825 684173 Urban 916604 482911 433693 3 Percentage Growth (2001-2011) Total 23.64 23.87 23.37 Rural 19.42 20.03 18.75 Urban 36.42 34.91 37.27 4. Percentage of Rural / Urban Population to total Population Total 100.00 100.00 100.00 Rural 72.62 71.90 73.44 Urban 27.38 28.10 26.56 5. Literates Absolute Total 7067233 4264671 2802562 Rural 4747950 2891749 1856201 Urban 2319283 1372922 946361 6. Literacy Rate (excluding 0-6 Population) Total 67.16 76.75 56.43 Rural 63.18 73.76 51.64 Urban 77.12 83.92 69.01 2 DIGEST OF STATISTICS 2013-14 I-AREA AND POPULATION Table No. 1.00 (Concld.) Jammu and Kashmir State at a Glance - 2011 Census . Persons Males females 7. 0-6 Population (Absolute) Total 2018905 1084355 934550 Rural 1593008 854141 738867 Urban 425897 230214 195683 8. Percentage of Child Population to total Population Total 16.10 16.33 15.84 Rural 17.49 17.89 17.05 Urban 12.41 12.34 12.49 9. -

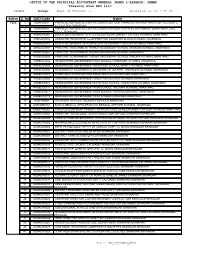

Treasury Wise DDO List Position As on : Name of Tresury

OFFICE OF THE PRINCIPAL ACCOUNTANT GENERAL JAMMU & KASHMIR- JAMMU Treasury wise DDO list Location : Srinagar Name of Tresury :- Position as on : 09-JAN-17 Active S. No DDO-Code Name YES 1 002FIN0001 FINANCIAL ADVISOR & CHIEF ACCOUNTS OFFICER FINANCIAL ADIVSOR AND CHIEF ACCOUNTS OFFICER SGR SRINAGAR 2 003FIN0001 FINANCIAL ADVISOR & CHIEF ACCOUNTS OFFICER O/O FA & CAO FINANCE DEARTMENT CIVIL SECTT. SRINAGAR 3 AHBAGR0001 BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER ACHABAL ANANTNAG 4 AHBAGR0002 ASSISTANT REGISTRAR CO-OPEREATIVE SOCIETIES BLOCK ACHABAL ANANTNAG 5 AHBAHD0001 BLOCK VETERINARY OFFICER BLOCK VETERINARY OFFICER ACHABAL ANANTNAG 6 AHBEDU0001 PRINCIPAL GOVERNMENT HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL AKINGAM ACHABAL ANANTNAG 7 AHBEDU0002 PRINCIPAL GOVERNMENT HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL ANANTNAG 8 AHBEDU0003 PRINCIPAL GOVERNMENT HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL HAKURA ACHABAL ANANTNAG 9 AHBEDU0004 HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL HARDPORA ACHABAL ANANTNAG 10 AHBEDU0005 HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT BOYS HIGH SCHOOL BRINTY ACHABAL ANANTNAG 11 AHBEDU0006 HEADMASTER HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT SCHOOL THAJIWARA ACHABAL ANANTNAG 12 AHBEDU0007 ZONAL EDUCATION OFFICER ZONAL EDUCATION OFFICER ANANTNAG 13 AHBEDU0008 HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL ACHABAL ANANTNAG 14 AHBEDU0009 HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT BOYS HIGH SCHOOL GOPALPORA ACHABAL ANANTNAG 15 AHBEDU0010 HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL TAILWANI ACHABAL ANANTNAG 16 AHBEDU0011 HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL TRAHPOO DISTRICT ANANTNAG 17 AHBEDU0012 HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL RANIPORA ANANTNAG 18 AHBFIN0001 -

Gujjars of Baramulla District in Kashmir Union Territory: an Observation Dilnaz1 and P

© 2018 JETIR November 2018, Volume 5, Issue 11 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Gujjars of Baramulla District in Kashmir Union Territory: An Observation Dilnaz1 and P. Durga Rao2 1Research Scholar Department of Sociology, School of Humanities Lovely Professional University,Phagwara-144411, Punjab, India 2Associate Professor Department of Sociology, School of Humanities Lovely Professional University, Phagwara-144411, Punjab, India. ABSTRACT Gujjars are semi nomadic tribes found in Baramulla district of Kashmir. Gujjars and Bakarwals both nomadic groups are predominantly living and oscillating in the Kandi areas of Kashmir and they are the third largest tribal groups in Jammu and Kashmir. Most of the Gujjars are nomads and they speak Gujjar which is locally is known as “Gujjari’. This tribe has 72 endogamous sub groups such as Phamda, Chechi, Paswal, Kasana, Katari, Daider, Pode,Jungle,Khatana,Kholi etc., differing in their dialects, food habits and customs depending on the locality. The present paper is an attempt to describe the ethnographic details of Gujjar tribe of Baramulla district in Kashmir Union Territory by employing observation, interview with key informants, and secondary source data. Keywords: Nomads, Clothes, Culture, Dead, Folk, Kinsmen, Marriage, Pollution, Ritual, Worship INTRODUCTION There are many tribal communities that are living throughout Jammu and Kashmir Union Territories (UTs) which become the main cause for the multicultural and multi-traditional nature of this area. The culture, traditions, and customs that these tribals carry makes this UTs different from the other States of the country. The tribal population is scattered in all regions of Jammu and Kashmir. It is being said that most of the tribes of Jammu and Kashmir are descendants of the famous families of Aryans.