View, and the Ethics of Empathy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dream of Morpheus: a Character Study of Narrative Power in Neil Gaiman’S the Sandman

– Centre for Languages and Literatur e English Studies The Dream of Morpheus: A Character Study of Narrative Power in Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman Astrid Dock ENGK01 Degree project in English Literature Autumn Term 2018 Centre for Languages and Literature Lund University Supervisor: Kiki Lindell Abstract This essay is primarily focused on the ambiguity surrounding Morpheus’ death in Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman. There is a divide in the character that is not reconciled within the comic: whether or not Morpheus is in control of the events that shape his death. Shakespeare scholars who have examined the series will have Morpheus in complete control of the narrative because of the similarities he shares with the character of Prospero. Yet the opposite argument, that Morpheus is a prisoner of Gaiman’s narrative, is enabled when he is compared to Milton’s Satan. There is sufficient evidence to support both readings. However, there is far too little material reconciling these two opposite interpretations of Morpheus’ character. The aim of this essay is therefore to discuss these narrative themes concerning Morpheus. Rather than Shakespeare’s Prospero and Milton’s Satan serving metonymic relationships with Morpheus, they should be respectively viewed as foils to further the ambiguous characterisation of the protagonist. With this reading, Morpheus becomes a character simultaneously devoid of, and personified by, narrative power. ii Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................... -

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

Feb COF C1:Customer 1/6/2012 2:54 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 18FEB 2012 FEB E COMIC H T SHOP’S CATALOG 02 FEBRUARY COF Apparel Shirt Ad:Layout 1 1/11/2012 1:45 PM Page 1 DC HEROES: “SUPER POWERS” Available only TURQUOISE T-SHIRT from your local comic shop! PREORDER NOW! SPIDER-MAN: DEADPOOL: “POOL SHOT” PLASTIC MAN: “DOUBLE VISION” BLACK T-SHIRT “ALL TIED UP” BURGUNDY T-SHIRT PREORDER NOW! CHARCOAL T-SHIRT PREORDER NOW! PREORDER NOW! COF Gem Page February:gem page v18n1.qxd 1/11/2012 1:29 PM Page 1 STAR WARS: MASS EFFECT: BLOOD TIES— HOMEWORLDS #1 BOBA FETT IS DEAD #1 DARK HORSE COMICS (OF 4) DARK HORSE COMICS WONDER WOMAN #8 DC COMICS RICHARD STARK’S PARKER: STIEG LARSSON’S THE SCORE HC THE GIRL WITH THE DRAGON IDW PUBLISHING TATTOO SPECIAL #1 DC COMICS / VERTIGO SECRET #1 IMAGE COMICS AMERICA’S GOT POWERS #1 (OF 6) AVENGERS VS. X-MEN: IMAGE COMICS VS. #1 (OF 6) MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 1/12/2012 10:00 AM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Girl Genius Volume 11: Agatha Heterodyne and the Hammerless Bell TP/HC G AIRSHIP ENTERTAINMENT Strawberry Shortcake Volume 1: Berry Fun TP G APE ENTERTAINMENT Bart Simpson‘s Pal, Milhouse #1 G BONGO COMICS Fanboys Vs. Zombies #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS 1 1 Roger Langridge‘s Snarked! Volume 1 TP G BOOM! STUDIOS/KABOOM! Lady Death Origins: Cursed #1 G BOUNDLESS COMICS The Shadow #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT The Shadow: Blood & Judgment TP G D. -

Fictional Tellers: a Radical Fictionalist Semantics for Fictional Discourse

Organon F 28 (1) 2021: 76–106 ISSN 2585-7150 (online) https://doi.org/10.31577/orgf.2021.28105 ISSN 1335-0668 (print) RESEARCH ARTICLE Fictional Tellers A Radical Fictionalist Semantics for Fictional Discourse Stefano Predelli* Received: 4 February 2020 / Accepted: 4 May 2020 Abstract: This essay proposes a dissolution of the so-called ‘semantic problem of fictional names’ by arguing that fictional names are only fictionally proper names. The ensuing idea that fictional texts do not encode propositional content is accompanied by an explanation of the contentful effects of fiction grounded on the idea of impartation. Af- ter some preliminaries about (referring and empty) genuine proper names, this essay explains how a fiction’s content may be conveyed by virtue of the fictional impartations provided by a fictional teller. This idea is in turn developed with respect to homodiegetic narratives such as Doyle’s Holmes stories and to heterodiegetic narratives such as Jane Austen’s Emma. The last parts of the essay apply this appa- ratus to cases of so-called ‘talk about fiction’, as in our commentaries about those stories and that novel. Keywords: Fiction; fictional names; narrative; proper names; seman- tics. * University of Nottingham https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8375-4611 Institute of Philosophy, Department of Philosophy. University of Nottingham Nottingham NG7 2RD, United Kingdom. [email protected] © The Author. Journal compilation © The Editorial Board, Organon F. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attri- bution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Public License (CC BY-NC 4.0). Fictional Tellers 77 0. -

‚Every Day Is 9/11!•Ž: Re-Constructing Ground Zero In

JUCS 4 (1+2) pp. 241–261 Intellect Limited 2017 Journal of Urban Cultural Studies Volume 4 Numbers 1 & 2 © 2017 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/jucs.4.1-2.241_1 MARTIN LUND Linnaeus University ‘Every day is 9/11!’: Re-constructing Ground Zero in three US comics ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This article analyses three comics series: writer Brian K. Vaughan and artist Tony comics Harris’ Ex Machina (August 2004–August 2010); writer Brian Wood and artist Ground Zero Riccardo Burchielli’s DMZ (November 2005–February 2012); and writer Garth 9/11 Ennis and artist Darick Robertson’s The Boys (October 2006–November 2012). archifictions Taking literary critic Laura Frost’s concept of ‘archifictions’ as its starting point, the War on Terror article discusses how these series frame the September 11 attacks on New York and architecture their aftermath, but its primary concern is with their engagement with the larger social ramifications of 9/11 and with the War on Terror, and with how this engage- ment is rooted in and centred on Ground Zero. It argues that this rooting allows these comics’ creators to critique post-9/11 US culture and foreign policy, but that it also, ultimately, serves to disarm the critique that each series voices in favour of closure through recourse to recuperative architecture. The attacks on September 11 continue to be felt in US culture. Comics are no exception. Comics publishers, large and small, responded immediately and comics about the attacks or the War on Terror have been coming out ever since. Largely missing from these comics, however, is an engagement with Ground Zero; after depicting the Twin Towers struck or falling, artists and writers rarely give the area a second thought. -

Passing: Intersections of Race, Gender, Class and Sexuality

Passing: Intersections of Race, Gender, Class and Sexuality Dana Christine Volk Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In ASPECT: Alliance for Social, Political, Ethical, and Cultural Thought Approved: David L. Brunsma, Committee Chair Paula M. Seniors Katrina M. Powell Disapproved: Gena E. Chandler-Smith May 17, 2017 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: passing, sexuality, gender, class, performativity, intersectionality Copyright 2017 Dana C. Volk Passing: Intersections of Race, Gender, Class, and Sexuality Dana C. Volk Abstract for scholarly and general audiences African American Literature engaged many social and racial issues that mainstream white America marginalized during the pre-civil, and post civil rights era through the use of rhetoric, setting, plot, narrative, and characterization. The use of passing fostered an outlet for many light- skinned men and women for inclusion. This trope also allowed for a closer investigation of the racial division in the United States. These issues included questions of the color line, or more specifically, how light-skinned men and women passed as white to obtain elevated economic and social status. Secondary issues in these earlier passing novels included gender and sexuality, raising questions as to whether these too existed as fixed identities in society. As such, the phenomenon of passing illustrates not just issues associated with the color line, but also social, economic, and gender structure within society. Human beings exist in a matrix, and as such, passing is not plausible if viewed solely as a process occurring within only one of these social constructs, but, rather, insists upon a viewpoint of an intersectional construct of social fluidity itself. -

PDF Download the Sandman Overture

THE SANDMAN OVERTURE: OVERTURE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK J. H. Williams, Neil Gaiman | 224 pages | 17 Nov 2015 | DC Comics | 9781401248963 | English | United States The Sandman Overture: Overture PDF Book Writer: Neil Gaiman Artist: J. The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. This would have been a better first issue. Nov 16, - So how do we walk the line of being a prequel, but still feeling relevant and fresh today on a visual level? Variant Covers. By continuing to use this website, you agree to their use. Click on the different category headings to find out more. Presented by MSI. Journeying into the realm of his sister Delirium , he learns that the cat was actually Desire in disguise. On an alien world, an aspect of Dream senses that something is very wrong, and dies in flames. Most relevant reviews. Williams III. The pair had never collaborated on a comic before "The Sandman: Overture," which tells the story immediately preceding the first issue of "The Sandman," collected in a book titled, "Preludes and Nocturnes. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. It's incredibly well written, but if you are looking for that feeling you had when you read the first issue of the original Sandman series, you won't find it here. Retrieved 13 March Logan's Run film adaptation TV adaptation. Notify me of new posts by email. Dreams, and by extension stories as we talked about in issue 1 , have meaning. Auction: New Other. You won't get that, not in these pages. -

Chinese Fables and Folk Stories

.s;^ '^ "It--::;'*-' =^-^^^H > STC) yi^n^rnit-^,; ^r^-'-,. i-^*:;- ;v^ r:| '|r rra!rg; iiHSZuBs.;:^::^: >» y>| «^ Tif" ^..^..,... Jj AMERICMJ V:B00lt> eOMI^^NY"' ;y:»T:ii;TOiriai5ia5ty..>:y:uy4»r^x<aiiua^^ nu,S i ;:;ti! !fii!i i! !!ir:i!;^ | iM,,TOwnt;;ar NY PUBLIC LIBRARY THE BRANCH LIBRARIES 3 3333 08102 9908 G258034 Digitized by the Internet Arciiive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/chinesefablesfolOOdavi CHINESE FABLES AND FOLK STORIES MARY HAYES DAVIS AND CHOW-LEUNG WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY YIN-CHWANG WANG TSEN-ZAN NEW YORK •:• CINCINNATI •: CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOKCOMPANY Copyright, 1908, by AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY Entered at Stationers' Hall, London Copyright, 1908, Tokyo Chinese Fables W. p. 13 y\9^^ PROPERTY OF THE ^ CITY OF MW YOBK G^X£y:>^c^ TO MY FRIEND MARY F. NIXON-ROULET PREFACE It requires much study of the Oriental mind to catch even brief glimpses of the secret of its mysterious charm. An open mind and the wisdom of great sympathy are conditions essential to making it at all possible. Contemplative, gentle, and metaphysical in their habit of thought, the Chinese have reflected profoundly and worked out many riddles of the universe in ways peculiarly their own. Realization of the value and need to us of a more definite knowledge of the mental processes of our Oriental brothers, increases wonder- fully as one begins to comprehend the richness, depth, and beauty of their thought, ripened as it is by the hidden processes of evolution throughout the ages. To obtain literal translations from the mental store- house of the Chinese has not been found easy of accom- plishment; but it is a more difficult, and a most elusive task to attempt to translate their fancies, to see life itself as it appears from the Chinese point of view, and to retell these impressions without losing quite all of their color and charm. -

John Constantine and the Homoaffective Question: an Analysis of LGBTI+ Representations in Superhero Comics and Animations

John Constantine and the homoaffective question: an analysis of LGBTI+ representations in superhero comics and animations JOHN CONSTANTINE AND THE HOMOAFFECTIVE QUESTION: AN ANALYSIS OF LGBTI+ REPRESENTATIONS IN SUPERHERO COMICS AND ANIMATIONS JOHN CONSTANTINE E A QUESTÃO HOMOAFETIVA: UMA ANÁLISE SOBRE REPRESENTAÇÕES LGBTI+ EM QUADRINHOS DE SUPER-HERÓIS E ANIMAÇÕES JOHN CONSTANTINE Y LA PREGUNTA HOMOAFFECTIVE: UN ANÁLISIS DE LAS REPRESENTACIONES LGBTI+ EN CÓMICS DE SUPERHÉROES Y ANIMACIONES Mário Jorge de PAIVA1 ABSTRACT: This article is an analysis of LGBTI + representations in comic books, superheroes, and children's animations. In particular, we will approach the character of DC Comics John Constantine, bisexual, because he is a hero of a major publisher, appearing alongside Batman, Superman etc. Our methodology is qualitative, based on a broad contribution containing: Michel Foucault, Sarane Alexandrian, James Green, João Trevisan, Dandara Cruz among others. Our conclusions involve seeing how there has really been a profound change over time. If before this type of question could not be addressed as much, or could not be addressed explicitly, today there is a greater opening for representations of LGBTI + characters. KEYWORDS: LGBTI+. Comics. Animations. John Constantine. Hellblazer. RESUMO: O presente artigo é uma análise das representações LGBTI+ em revistas de super-heróis e animações. Abordaremos mais a personagem da DC Comics John Constantine, bissexual, por ele ser um herói de uma grande editora, aparecendo junto ao Batman, Superman etc. Nossa metodologia é qualitativa, se pautando em uma análise inicial do campo de estudos e na sequência em uma análise mais aprofundada da própria personagem Constantine. Possuímos um aporte teórico que envolve, entre outros autores: Michel Foucault, Sarane Alexandrian e Dandara Cruz. -

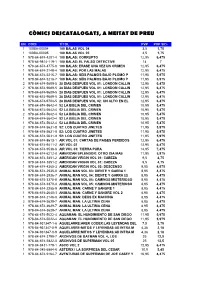

Llistat Còmics Descatalogats.Xml

CÒMICS DESCATALOGATS, A MEITAT DE PREU UN. CODI TÍTOL PVP PVP 50% 1 100BA-00004 100 BALAS VOL 04 3,5 1,75 1 100BA-00005 100 BALAS VOL 05 3,5 1,75 1 978-84-674-4201-4 100 BALAS: CORRUPTO 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-9814-119-1 100 BALAS: EL FALSO DETECTIVE 14 7 1 978-84-674-4775-0 100 BALAS: ERASE UNA VEZ UN CRIMEN 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-2148-4 100 BALAS: POR LAS MALAS 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-5216-7 100 BALAS: SEIS PALMOS BAJO PLOMO P 11,95 5,975 1 978-84-674-5216-7 100 BALAS: SEIS PALMOS BAJO PLOMO P 11,95 5,975 2 978-84-674-9689-5 28 DIAS DESPUES VOL 01: LONDON CALLIN 12,95 6,475 2 978-84-674-9689-5 28 DIAS DESPUES VOL 01: LONDON CALLIN 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-9689-5 28 DIAS DESPUES VOL 01: LONDON CALLIN 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-9689-5 28 DIAS DESPUES VOL 01: LONDON CALLIN 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-9704-5 28 DIAS DESPUES VOL 02: UN ALTO EN EL 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-5642-4 52 LA BIBLIA DEL CRIMEN 10,95 5,475 5 978-84-674-5642-4 52 LA BIBLIA DEL CRIMEN 10,95 5,475 2 978-84-674-5642-4 52 LA BIBLIA DEL CRIMEN 10,95 5,475 1 978-84-674-5642-4 52 LA BIBLIA DEL CRIMEN 10,95 5,475 1 978-84-674-5642-4 52 LA BIBLIA DEL CRIMEN 10,95 5,475 2 978-84-674-5631-8 52: LOS CUATRO JINETES 11,95 5,975 1 978-84-674-5631-8 52: LOS CUATRO JINETES 11,95 5,975 3 978-84-674-5631-8 52: LOS CUATRO JINETES 11,95 5,975 1 978-84-674-8613-1 AIR VOL 01: CARTAS DE PAISES PERDIDOS 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-9411-2 AIR VOL 02 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-9538-6 AIR VOL 03: TIERRA PURA 14,95 7,475 1 978-84-674-6212-8 AMERICAN SPLENDOR: OTRO DIA MAS 11,95 5,975 1 978-84-674-3851-2 -

The Criminalization of Free Speech in DMZ Angus Nurse School of Law, Middlesex University, GB [email protected]

Angus Nurse, ‘See No Evil, Print No Evil: The Criminalization of THE COMICS GRID Free Speech in DMZ ’ (2017) 7(1): 10 The Comics Grid: Journal Journal of comics scholarship of Comics Scholarship, DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/cg.88 RESEARCH See No Evil, Print No Evil: The Criminalization of Free Speech in DMZ Angus Nurse School of Law, Middlesex University, GB [email protected] This article examines contemporary notions on free speech and the criminalisation of journalistic expression since 9/11, via discussion of Brian Wood’s DMZ comics (DC Vertigo). Free speech and the importance of a free press are widely accepted notions, yet journalistic and artistic freedom is arguably under attack in our post-9/11 world (Ash, 2016; Article 19, 2007). State responses to global terror threats have criminalised free speech, particularly speech seen as ‘glorifying’ or ‘supporting’ terrorism via anti-terror or restrictive media laws. This article examines these issues via DMZ ’s discussion of a second American civil war in which freedom of the press has all but disappeared, arguing that DMZ ’s ‘War on Terror’ narrative and depiction of controlled news access serve as allegories for contemporary free speech restrictions. DMZ illustrates contemporary concerns about a perceived social problem in its representation of corruption, abuse of power and restrictions on the public’s right to know. Keywords: 9/11; censorship; free speech; human rights; press freedom Welcome to the DMZ This article examines contemporary notions on free speech and the criminalisation of journalistic expression in a post-9/11 world via discussion of Brian Wood and Riccardo Burchielli’s DMZ comics (DC Vertigo November 2005 to February 2012). -

V for Vendetta’: Book and Film

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE ESTUDOS ANGLÍSTICOS “9 into 7” Considerations on ‘V for Vendetta’: Book and Film. Luís Silveiro MESTRADO EM ESTUDOS INGLESES E AMERICANOS (Estudos Norte-Americanos: Cinema e Literatura) 2010 UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE ESTUDOS ANGLÍSTICOS “9 into 7” Considerations on ‘V for Vendetta’: Book and Film. Luís Silveiro Dissertação orientada por Doutora Teresa Cid MESTRADO EM ESTUDOS INGLESES E AMERICANOS (Estudos Norte-Americanos: Cinema e Literatura) 2010 Abstract The current work seeks to contrast the book version of Alan Moore and David Lloyd‟s V for Vendetta (1981-1988) with its cinematic counterpart produced by the Wachowski brothers and directed by James McTeigue (2005). This dissertation looks at these two forms of the same enunciation and attempts to analise them both as cultural artifacts that belong to a specific time and place and as pseudo-political manifestos which extemporize to form a plethora of alternative actions and reactions. Whilst the former was written/drawn during the Thatcher years, the film adaptation has claimed the work as a herald for an alternative viewpoint thus pitting the original intent of the book with the sociological events of post 9/11 United States. Taking the original text as a basis for contrast, I have relied also on Professor James Keller‟s work V for Vendetta as Cultural Pastiche with which to enunciate what I consider to be lacunae in the film interpretation and to understand the reasons for the alterations undertaken from the book to the screen version. An attempt has also been made to correlate Alan Moore‟s original influences into the medium of a film made with a completely different political and cultural agenda. -

Super Satan: Milton’S Devil in Contemporary Comics

Super Satan: Milton’s Devil in Contemporary Comics By Shereen Siwpersad A Thesis Submitted to Leiden University, Leiden, the Netherlands in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MA English Literary Studies July, 2014, Leiden, the Netherlands First Reader: Dr. J.F.D. van Dijkhuizen Second Reader: Dr. E.J. van Leeuwen Date: 1 July 2014 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………... 1 - 5 1. Milton’s Satan as the modern superhero in comics ……………………………….. 6 1.1 The conventions of mission, powers and identity ………………………... 6 1.2 The history of the modern superhero ……………………………………... 7 1.3 Religion and the Miltonic Satan in comics ……………………………….. 8 1.4 Mission, powers and identity in Steve Orlando’s Paradise Lost …………. 8 - 12 1.5 Authority, defiance and the Miltonic Satan in comics …………………… 12 - 15 1.6 The human Satan in comics ……………………………………………… 15 - 17 2. Ambiguous representations of Milton’s Satan in Steve Orlando’s Paradise Lost ... 18 2.1 Visual representations of the heroic Satan ……………………………….. 18 - 20 2.2 Symbolic colors and black gutters ……………………………………….. 20 - 23 2.3 Orlando’s representation of the meteor simile …………………………… 23 2.4 Ambiguous linguistic representations of Satan …………………………... 24 - 25 2.5 Ambiguity and discrepancy between linguistic and visual codes ………... 25 - 26 3. Lucifer Morningstar: Obedience, authority and nihilism …………………………. 27 3.1 Lucifer’s rejection of authority ………………………..…………………. 27 - 32 3.2 The absence of a theodicy ………………………………………………... 32 - 35 3.3 Carey’s flawed and amoral God ………………………………………….. 35 - 36 3.4 The implications of existential and metaphysical nihilism ……………….. 36 - 41 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………………. 42 - 46 Appendix ……………………………………………………………………………… 47 Figure 1.1 ……………………………………………………………………… 47 Figure 1.2 ……………………………………………………………………… 48 Figure 1.3 ……………………………………………………………………… 48 Figure 1.4 ……………………………………………………………………….