‚Every Day Is 9/11!•Ž: Re-Constructing Ground Zero In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Mar Customer Order Form

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18MAR 2013 MAR COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Mar Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 3:35:28 PM Available only STAR WARS: “BOBA FETT CHEST from your local HOLE” BLACK T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! MACHINE MAN THE WALKING DEAD: ADVENTURE TIME: CHARCOAL T-SHIRT “KEEP CALM AND CALL “ZOMBIE TIME” Preorder now! MICHONNE” BLACK T-SHIRT BLACK HOODIE Preorder now! Preorder now! 3 March 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 2/7/2013 10:05:45 AM X #1 kiNG CoNaN: Dark Horse ComiCs HoUr oF THe DraGoN #1 Dark Horse ComiCs GreeN Team #1 DC ComiCs THe moVemeNT #1 DoomsDaY.1 #1 DC ComiCs iDW PUBlisHiNG THe BoUNCe #1 imaGe ComiCs TeN GraND #1 UlTimaTe ComiCs imaGe ComiCs sPiDer-maN #23 marVel ComiCs Mar13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 2:21:38 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 2 #1 l ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT Uber #1 l AVATAR PRESS Suicide Risk #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Clive Barker’s New Genesis #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Marble Season HC l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Black Bat #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 1 Battlestar Galactica #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Grimm #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Wars In Toyland HC l ONI PRESS INC. The From Hell Companion SC l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Valiant Masters: Shadowman Volume 1: The Spirits Within HC l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Rurouni Kenshin Restoration Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Soul Eater Soul Art l YEN PRESS BOOKS & MAGAZINES 2 Doctor Who: Who-Ology Official Miscellany HC l DOCTOR WHO / TORCHWOOD Doctor Who: The Official -

BREAKING Newsrockville, MD August 19, 2019

MEDIA KIT BREAKING NEWS Rockville, MD August 19, 2019 THE BOYS by Garth Ennis and Darick Robertson Coming to GraphicAudio® A Movie in Your Mind® in Early 2020 GraphicAudio® is thrilled to announce a just inked deal with DYNAMITE COMICS to produce and publish all 6 Omnibus Volumes of THE BOYS directly from the comics and scripted and produced in their unique audio entertainment format. The creative team at GraphicAudio® plans to make the adaptations as faithful as possible to the Graphic Novel series. The series is set between 2006–2008 in a world where superheroes exist. However, most of the su- perheroes in the series' universe are corrupted by their celebrity status and often engage in reckless behavior, compromising the safety of the world. The story follows a small clandestine CIA squad, informally known as "The Boys", led by Butcher and also consisting of Mother's Milk, the French- man, the Female, and new addition "Wee" Hughie Campbell, who are charged with monitoring the superhero community, often leading to gruesome confrontations and dreadful results; in parallel, a key subplot follows Annie "Starlight" January, a young and naive superhero who joins the Seven, the most prestigious– and corrupted – superhero group in the world and The Boys' most powerful enemies. Amazon Prime released THE BOYS Season 1 last month. Joseph Rybandt, Executive Editor of Dynamite and Editor of The Boys says, “While I did not grow up anywhere near the Golden Age of Radio, I have loved the medium of radio and audio dramas almost my entire life. Podcasts make my commute bearable to this day. -

Urzedowy Wykaz Drukow

ISSNISSN 2719-308X 1689-6521 URZĘDOWY WYKAZ DRUKÓW WYDANYCH W RZECZYPOSPOLITEJ POLSKIEJ PRZEWODNIK BIBLIOGRAFICZNY BIBLIOTEKA NARODOWA R. 7675(87) (88) Warszawa, Warszawa, 23–31 15–21 grudnia czerwca 2019 2020 r. r. Nr Nr 52 24 Poz. Poz. 37771–38349 18611–19504 WYKAZ DZIAŁÓW UKD 0 DZIAŁ OGÓLNY. Nauka i wiedza. Bibliologia. 622 Górnictwo Informacja. Bibliografia. Bibliotekarstwo. 629 Technika środków transportu Organizacje. Muzea 63 Rolnictwo 0/9(03) Encyklopedie i leksykony o treści ogólnej 630 Leśnictwo 004 Informatyka 631/635 Uprawa roślin. Ogrodnictwo 005 Zarządzanie 636/639 Zootechnika.Weterynaria 07 Mass media. Środki masowego przekazu. 64 Gospodarstwo domowe. Hotelarstwo. Medioznawstwo Gastronomia 1 FILOZOFIA 65 Telekomunikacja. Przemysł poligraficzny. 159.9 Psychologia Działalność wydawnicza 2 RELIGIA. TEOLOGIA 656 Organizacja transportu 27 Chrześcijaństwo. Kościoły chrześcijańskie 657 Rachunkowość. Księgowość 272 Katolicyzm. Kościół rzymskokatolicki 658 Organizacja przedsiębiorstw. Organizacja 3 NAUKI SPOŁECZNE i technika handlu 30 Metodologia nauk społecznych. Polityka 659 Reklama. Public relations społeczna. Gender studies. Socjografia 66/68 Przemysł. Rzemiosło 311+314 Statystyka. Demografia 69 Przemysł budowlany 316 Socjologia 7 SZTUKA. ROZRYWKI. SPORT 32 Nauki polityczne. Polityka 71 Planowanie przestrzenne. Urbanistyka. 33 Nauki ekonomiczne. Praca. Gospodarka Architektura krajobrazu regionalna. Spółdzielczość 72 Architektura 336 Finanse. Podatki 73/76 Sztuki plastyczne. Rzeźba. Rysunek. 338/339 Gospodarka narodowa. Handel. Gospodarka Rzemiosło artystyczne. Malarstwo. Grafika światowa 77 Fotografia 338.48 Turystyka 78 Muzyka 34+351/354 Prawo. Administracja publiczna 79 Rozrywki towarzyskie. Taniec. Zabawy. Gry 355/359 Wojskowość. Nauki wojskowe. Sztuka wojenna. 791/792 Film. Teatr Siły zbrojne 796/799 Sport. Kultura fizyczna 36 Opieka społeczna. Ubezpieczenia. 8 JĘZYKOZNAWSTWO. NAUKA Konsumeryzm O LITERATURZE. LITERATURA PIĘKNA 37 Oświata.Wychowanie. -

Garth Ennis Battlefields: Dear Billy Volume 2 Free Ebook

FREEGARTH ENNIS BATTLEFIELDS: DEAR BILLY VOLUME 2 EBOOK Peter Snejbjerg,Garth Ennis | 88 pages | 07 Jul 2009 | Dynamic Forces Inc | 9781606900574 | English | Runnemede, United States Garth Ennis' Battlefields Volume 2: Dear Billy : Garth Ennis : Nurse Carrie Sutton is caught up in the Japanese invasion of Singapore, suffering horrors beyond her wildest nightmares- and survives. Now she attempts to start her life anew, buoyed up by a growing friendship with a wounded pilot- only for fate to deliver up the last thing she ever expected. Carrie at last has a chance for revenge In the midst of a world torn apart by war, you can fight and you can win- but you still might not get the things you truly want. Featuring the entire three issue series, a complete cover gallery, and a look at the layouts and pencil art of Peter Snejbjerg! This character has Garth Ennis Battlefields: Dear Billy Volume 2 appeared with the Green Hornet in film, television, book and comic book versions. Kato was the Hornet's With her ever-present pout and sassy disposition, Grumpy Cat has won the A number of Sniegoski's works have been related to the Buffyverse, the fictional universe established by TV series, All Rights Reserved. Privacy Policy. Kato is a character from The Green Hornet series. Frank Miller born January 27, is an American writer, Garth Ennis Battlefields: Dear Billy Volume 2 and film director best known for his dark, film noir-style comic book stories and graphic novels for Dark Horse Comics, Tom Sniegoski is a novelist, comic book writer and pop culture journalist. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

The Criminalization of Free Speech in DMZ Angus Nurse School of Law, Middlesex University, GB [email protected]

Angus Nurse, ‘See No Evil, Print No Evil: The Criminalization of THE COMICS GRID Free Speech in DMZ ’ (2017) 7(1): 10 The Comics Grid: Journal Journal of comics scholarship of Comics Scholarship, DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/cg.88 RESEARCH See No Evil, Print No Evil: The Criminalization of Free Speech in DMZ Angus Nurse School of Law, Middlesex University, GB [email protected] This article examines contemporary notions on free speech and the criminalisation of journalistic expression since 9/11, via discussion of Brian Wood’s DMZ comics (DC Vertigo). Free speech and the importance of a free press are widely accepted notions, yet journalistic and artistic freedom is arguably under attack in our post-9/11 world (Ash, 2016; Article 19, 2007). State responses to global terror threats have criminalised free speech, particularly speech seen as ‘glorifying’ or ‘supporting’ terrorism via anti-terror or restrictive media laws. This article examines these issues via DMZ ’s discussion of a second American civil war in which freedom of the press has all but disappeared, arguing that DMZ ’s ‘War on Terror’ narrative and depiction of controlled news access serve as allegories for contemporary free speech restrictions. DMZ illustrates contemporary concerns about a perceived social problem in its representation of corruption, abuse of power and restrictions on the public’s right to know. Keywords: 9/11; censorship; free speech; human rights; press freedom Welcome to the DMZ This article examines contemporary notions on free speech and the criminalisation of journalistic expression in a post-9/11 world via discussion of Brian Wood and Riccardo Burchielli’s DMZ comics (DC Vertigo November 2005 to February 2012). -

Ebook Download the Boys Volume 6: Self-Preservation Society Limited

THE BOYS VOLUME 6: SELF-PRESERVATION SOCIETY LIMITED EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Garth Ennis | 192 pages | 26 Apr 2011 | Dynamic Forces Inc | 9781606901410 | English | Runnemede, United States The Boys Volume 6: Self-Preservation Society Limited Edition PDF Book This book contains "secret origin" stories for three of The Boys, although two of those origins come from a highly unreliable narrator. Issue 3S- 1ST. Written by Garth Ennis. Add to cart Very Fine. Can I cancel or get a refund on my order? Volume 3 - 1st printing. One of the world's most powerful superteams decides to hit our heroes, all guns blazing, and the Female is the first to fall into their lethal trap. Plus, the Boys origins That's when you call in The Boys! Add to wishlist. Add to cart Very Fine. Volume 2 - 1st printing. Pulping teenage supes is one thing, but how will our heroes fare against Soldier Boy, Mind-Droid, Swatto, the Crimson Countess, and the Nazi juggernaut known as Stormfront? Issue ST. Limited Signed Edition - Volume 2 - 2nd and later printings. Dynamite is celebrating our 5th anniversary and is proud to present a special anniversary hardcover edition of the comic book series everyone is talking about! All kinds of secrets await our hero, beginning with the terrible story of the first supes to see action in World War Two. JavaScript must be enabled to use this site. No library descriptions found. From tragedy in Harlem to the slaughter on the Brooklyn Bridge, from the festival of Les Saints De Haw-Haw to the horror lurking under Tokyo, this is a journey of discovery like no other - with only the flickering lamp of insanity to light the way. -

Growing up with Vertigo: British Writers, Dc, and the Maturation of American Comic Books

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ScholarWorks @ UVM GROWING UP WITH VERTIGO: BRITISH WRITERS, DC, AND THE MATURATION OF AMERICAN COMIC BOOKS A Thesis Presented by Derek A. Salisbury to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in History May, 2013 Accepted by the Faculty of the Graduate College, The University of Vermont, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, specializing in History. Thesis Examination Committee: ______________________________________ Advisor Abigail McGowan, Ph.D ______________________________________ Melanie Gustafson, Ph.D ______________________________________ Chairperson Elizabeth Fenton, Ph.D ______________________________________ Dean, Graduate College Domenico Grasso, Ph.D March 22, 2013 Abstract At just under thirty years the serious academic study of American comic books is relatively young. Over the course of three decades most historians familiar with the medium have recognized that American comics, since becoming a mass-cultural product in 1939, have matured beyond their humble beginnings as a monthly publication for children. However, historians are not yet in agreement as to when the medium became mature. This thesis proposes that the medium’s maturity was cemented between 1985 and 2000, a much later point in time than existing texts postulate. The project involves the analysis of how an American mass medium, in this case the comic book, matured in the last two decades of the twentieth century. The goal is to show the interconnected relationships and factors that facilitated the maturation of the American sequential art, specifically a focus on a group of British writers working at DC Comics and Vertigo, an alternative imprint under the financial control of DC. -

Customer Order Form

#386 | NOV20 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE NOV 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Nov20 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:23:12 AM Nov20 Ad DST Rogue.indd 1 10/8/2020 11:07:39 AM PREMIER COMICS HAHA #1 IMAGE COMICS 30 RAIN LIKE HAMMERS #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 CRIMSON FLOWER #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 62 AVATAR: THE NEXT SHADOW #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 64 MARVEL ACTION: CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING 104 KING IN BLACK: BLACK KNIGHT #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-6 RED SONJA: THE SUPER POWERS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 126 ABBOTT: 1973 #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 158 Nov20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:24:32 AM COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS · PRINT Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE FEATURED ITEMS Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS I Breathed A Body #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS 1 Delicates TP l ONI PRESS l I Breathed A Body #1 AFTERSHOCK COMICS 1 The Cutting Edge: Devil’s Mirror #1 l TITAN COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS Knights of Heliopolis HC l TITAN COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Blade Runner 2029 #2 l TITAN COMICS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars Insider #200 l TITAN COMICS Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Comic Book Creator #25 l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Bloodshot #9 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Vagrant Queen Volume 2: A Planet Called Doom TP l VAULT COMICS Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. -

The Graphic Novel As Advanced Literacy Tool

Available online at www.jmle.org The National Association for Media Literacy Education’s Journal of Media Literacy Education 2:1 (2010) 57 - 64 Voices from the Field The Graphic Novel as Advanced Literacy Tool David Seelow Excelsior College & Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, NY, USA Over the first decade of the 21st century, Well-done graphic novels offer teachers an- comics have emerged as a strong literacy tool both in other tool to be used in the classroom and can the official school curriculum and in the after school enrich the students’ experiences as a new way movement. For example, the New York City Comic of imparting information, serving as transi- Book Museum has a curriculum entitled C.O.M.I.C.S. tions into more print intensive works, enticing Curriculum - “Challenging Objective Minds: an reluctant readers into prose books and, in some Instructional Comicbook Series,” the first museum-ap- cases, offering literary experiences that linger proved educational program designed to bring comic in the mind long after the book is finished (115). books into the classroom.1 Comics are particularly In fact, I want to argue in this paper that graphic novels motivating for reluctant readers, and also for English are not just transitions to more advanced prose works, Language Learners. Pictures provide a context, and the but that graphic novels, in themselves, are comparable stories introduce students to all the elements of fiction to the best prose works. Furthermore, graphic novels discussed in a Language Arts classroom.2 As vehicles offer advanced literacy skills to a wide range of stu- for discussion, comics offer a gateway to more ad- dents, not just reluctant readers, but equally, regular vanced works of literature discussed in middle school and advanced placement students. -

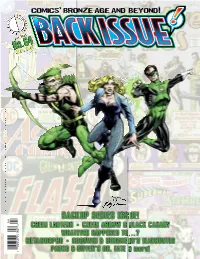

Backup Series Issue! 0 8 Green Lantern • Green Arrow & Black Canary 2 6 7 7

0 4 No.64 May 201 3 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 METAMORPHO • GOODWIN & SIMONSON’S MANHUNTER GREEN LANTERN • GREEN ARROW & BLACK CANARY COMiCs PASKO & GIFFEN’S DR. FATE & more! , WHATEVER HAPPENED TO…? BACKUP SERIES ISSUE! bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD i . Volume 1, Number 64 May 2013 Celebrating the Best Comics of Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTISTS Mike Grell and Josef Rubinstein COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 PROOFREADER Rob Smentek FLASHBACK: The Emerald Backups . .3 Green Lantern’s demotion to a Flash backup and gradual return to his own title SPECIAL THANKS Jack Abramowitz Robert Greenberger FLASHBACK: The Ballad of Ollie and Dinah . .10 Marc Andreyko Karl Heitmueller Green Arrow and Black Canary’s Bronze Age romance and adventures Roger Ash Heritage Comics Jason Bard Auctions INTERVIEW: John Calnan discusses Metamorpho in Action Comics . .22 Mike W. Barr James Kingman The Fab Freak of 1001-and-1 Changes returns! With loads of Calnan art Cary Bates Paul Levitz BEYOND CAPES: A Rose by Any Other Name … Would be Thorn . .28 Alex Boney Alan Light In the back pages of Lois Lane—of all places!—sprang the inventive Rose and the Thorn Kelly Borkert Elliot S! Maggin Rich Buckler Donna Olmstead FLASHBACK: Seven Soldiers of Victory: Lost in Time Again . .33 Cary Burkett Dennis O’Neil This Bronze Age backup serial was written during the Golden Age Mike Burkey John Ostrander John Calnan Mike Royer BEYOND CAPES: The Master Crime-File of Jason Bard .