Tentmaking and Tourism in Indo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 2019

OCTOBER 2019 Love, marriage and unbelief CHURCH AND HOME LIFE WITH A NON-CHRISTIAN PLUS Do we really want God’s will done? Persecution in 21st-century Sydney PRINT POST APPROVED 100021441 ISSN 2207-0648 ISSN 100021441 APPROVED PRINT POST CONTENTS COVER Do we know how to support and love friends and family when a Christian is married to a non- Christian? “I felt there was a real opportunity... to Sydney News 3 acknowledge God’s Australian News 4 hand in the rescue”. Simon Owen Sydney News World News 5 6 Letters Southern cross OCTOBER 2019 Changes 7 volume 25 number 9 PUBLISHER: Anglican Media Sydney Essay 8 PO Box W185 Parramatta Westfield 2150 PHONE: 02 8860 8860 Archbishop Writes 9 FAX: 02 8860 8899 EMAIL: [email protected] MANAGING EDITOR: Russell Powell Cover Feature 10 EDITOR: Judy Adamson 2019 ART DIRECTOR: Stephen Mason Moore is More 11 ADVERTISING MANAGER: Kylie Schleicher PHONE: 02 8860 8850 OCTOBER EMAIL: [email protected] Opinion 12 Acceptance of advertising does not imply endorsement. Inclusion of advertising material is at the discretion of the publisher. Events 13 cross SUBSCRIPTIONS: Garry Joy PHONE: 02 8860 8861 Culture 14 EMAIL: [email protected] $44.00 per annum (Australia) Southern 2 SYDNEY NEWS Abortion protests have limited success Choose life: participants in the Sydney protest against the abortion Bill before NSW Parliament. TWO MAJOR PROTESTS AND TESTIMONY TO A PARLIAMENTARY INQUIRY BY ARCHBISHOP GLENN Davies and other leaders has failed to stop a Bill that would allow abortion right up until birth. But the interventions and support of Christian MPs resulted in several amendments in the Upper House of State Parliament. -

Poetry and Public Speech: Three Traces

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online Poetry and Public Speech: Three Traces DAVID McCOOEY Deakin University Contemporary poetry is routinely seen as ‘marginal’ to public culture. As Simon Caterson wrote in the Sunday Age in 2005, ‘Poets have never been more numerous, and never less visible’ (31). The simultaneous ubiquity and marginality of poets is usually noted in terms of poetry having lost its status as a form of public speech. The American critic Dana Gioia, in his oft-cited essay ‘Can Poetry Matter?’ (1991), asserts that ‘Without a role in the broader culture…talented poets lack the confidence to create public speech’ (10). Such a condition is often noted in nostalgic terms, in which a golden era—bardic or journalistic—is evoked to illustrate contemporary poetry’s lack. In the bardic model, the poet gains status by speaking for the people in a form that is public but not official. Gioia evokes such a tradition himself when he describes poets as ‘Like priests in a town of agnostics’ who ‘still command a certain residual prestige’ (1). In the Australian context, Les Murray has most often been associated with such a bardic role (McDonald, 1976; Bourke, 1988). In the journalistic model, one evoked by Jamie Grant (2001), the poet is presented as a spokesperson, authoritatively commenting on public and topical events. This model is supported by Murray in his anthology The New Oxford Book of Australian Verse (1986). In the introduction to this work, the only historical observation Murray makes is that ‘most Australian poetry in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries first saw the light of day in newspapers’ (xxii), before poetry became marginalised in small literary magazines. -

Appendices and Bibliography

Appendices and Bibliography APPENDICES 577 Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by Religious and Other Non-Government Organisations 578 Appendices and Bibliography Appendix 1—Submission guide INQUIRY INTO THE HANDLING OF CHILD ABUSE BY RELIGIOUS AND OTHER ORGANISATIONS SUBMISSION GUIDE 1. WHO CAN MAKE SUBMISSIONS? 3. WHAT SORT OF SUBMISSIONS CAN BE MADE? All interested parties can make submissions to the Submissions may be in writing or, where an Inquiry. The bi-partisan Family and Community individual does not wish to make a written Development Committee is seeking submissions submission, on a verbal basis only. from both individuals and organisations in relation All submissions are treated as public, unless to its Terms of Reference to the Inquiry. otherwise requested. The Committee can receive The Committee welcomes submissions from written and oral evidence on a confidential basis victims of child abuse and others who have been where this is requested and agreed to by the affected by the consequences of such abuse. Committee. This will generally be in situations in which victims believe that giving evidence It acknowledges that preparing submissions and publicly may have an adverse effect on them or giving evidence to such an Inquiry can be a very their families. difficult experience for victims of child abuse and their supporters. This Guide is intended to assist in Please indicate if you want your submission the process of preparing a submission. treated as confidential and provide a brief explanation. 2. WHAT EVIDENCE CAN SUBMISSIONS INCLUDE? 4. TERMS OF REFERENCE The Committee is seeking information relating to: The Committee has been asked by the Victorian • The causes and effects of criminal abuse within Government to consider and report to the religious and other non-government Parliament on the processes by which religious organisations. -

Newsletter No 38 March 2009 President's Comments

Newsletter No 38 March 2009 ISSN 1836-5116 crosses or stained glass windows. These were regarded President’s Comments as idolatrous. This column is being written on the day after Ash Most of the recently built Sydney Anglican Churches Wednesday. This year Ash Wednesday cannot but fit this pattern- they are plain and functional with help to remind us of the tragic Victorian bushfires minimal decoration and generally devoid of religious and the thousands of people who have been so deeply symbolism. They are places to meet with others and the affected by them. focus of attention is a stage with a podium and As Anglicans we are also aware of the two microphone. We no longer have services in such places, communities, Kinglake and Marysville that have seen we have meetings and the buildings express that their churches destroyed and many of their parishioners understanding. rendered homeless. I have to confess that my experience over twenty years of ordained ministry has changed my thinking on the value of the building and made me question the ‘rain shelter’ view. God clearly has a sense of humour for if you had told me at the age of 16 that 40 years later I would be the rector of an Anglican parish with two heritage church buildings complete with stained glass, crosses, candles and liturgical colours I would have been incredulous. So how should we regard our church buildings? To me they function somewhat like the sacraments. They are visible reminders of a spiritual reality, namely the gathered Christian community. For those on the outside, the Church building bears witness to the fact that the people who meet there take God seriously. -

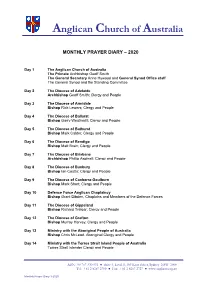

Monthly-Prayer-Diary-3-2020.Pdf

Anglican Church of Australia MONTHLY PRAYER DIARY – 2020 Day 1 The Anglican Church of Australia The Primate Archbishop Geoff Smith The General Secretary Anne Hywood and General Synod Office staff The General Synod and the Standing Committee Day 2 The Diocese of Adelaide Archbishop Geoff Smith; Clergy and People Day 3 The Diocese of Armidale Bishop Rick Lewers; Clergy and People Day 4 The Diocese of Ballarat Bishop Garry Weatherill; Clergy and People Day 5 The Diocese of Bathurst Bishop Mark Calder; Clergy and People Day 6 The Diocese of Bendigo Bishop Matt Brain; Clergy and People Day 7 The Diocese of Brisbane Archbishop Phillip Aspinall; Clergy and People Day 8 The Diocese of Bunbury Bishop Ian Coutts; Clergy and People Day 9 The Diocese of Canberra-Goulburn Bishop Mark Short; Clergy and People Day 10 Defence Force Anglican Chaplaincy Bishop Grant Dibden, Chaplains and Members of the Defence Forces Day 11 The Diocese of Gippsland Bishop Richard Treloar; Clergy and People Day 12 The Diocese of Grafton Bishop Murray Harvey; Clergy and People Day 13 Ministry with the Aboriginal People of Australia Bishop Chris McLeod, Aboriginal Clergy and People Day 14 Ministry with the Torres Strait Island People of Australia Torres Strait Islander Clergy and People ABN: 90 767 330 931 ● Suite 4, Level 5, 189 Kent Street, Sydney NSW 2000 Tel: +61 2 8267 2700 ● Fax: +61 2 8267 2727 ● www.anglican.org.au Monthly Prayer Diary 3-2020 Day 15 The Diocese of Melbourne Archbishop Philip Freier; Clergy and People Day 16 The Diocese of Newcastle Bishop Peter Stuart; -

Finding God's Peace Through God's Word

ISSN 1837-8447 Spring 2020 MAGAZINE Finding God’s peace through God’s Word Bringing God’s peace to J.I. Packer: The latest Christian traumatised communities The holy scholar resources for you Page 2–4 Page 18–21 Page 33–39 We are all in this together ear Anna, Bronwyn, Graham, Margaret, Beverly, Pete, Miriam, Bruce, Angela, Yvonne, Elizabeth, June, Mike, Harold Dand other friends of Bible Society, Eternity and Koorong, Let me first say ‘Thank You.’ I loved all your comments and ideas for a new name for our new combined magazine. Your contributions were fantastic! Sowing for Eternity. Eternal Seed. Beyond. Given. Trinity. However, the overwhelming consensus was to stick with Bible Society Magazine, as that name says it all. So, welcome to Bible Society Magazine issue 2. We will continue fine-tuning the look and feel of the different sections of our magazine. I mentioned in the last edition about our Staff Devotion on Wednesdays. Over the past few weeks I have been leading a series on culture. In 2 Timothy 1:13, Paul tells Timothy to ‘hold fast the pattern of sound words which you have heard from me, in faith and love which are in Christ Jesus.’ (NKJV) As I spoke to the Bible Society team across Australia, I painted the picture of a patchwork quilt. All the different squares, different pat- terns, can look mismatched or disjointed up close, but when knitted together they form a magnificent cohesive whole. As Christians we are urged to hold fast to the pattern of words which have been laid down, knitted together, in the Bible and by Christian thinkers, theologians, writers, pastors, leaders, friends, over the centuries since Paul wrote that letter. -

Michael Leunig the Night We Lost Our Marbles Sans.Fm

M ICHAEL LEUNIG T HE NIGHT WE LOST OUR MARBLES D ESERT JOY 2016 Acrylic on canvas 106 × 122 cm T HE NIGHT WE LOST OUR MARBLES II 2016 Acrylic on linen 76 × 92 cm T HE TIDE COMES IN 2016 Acrylic on canvas 91 × 76 cm P ILGRIM 2016 Acrylic on linen 92 × 71 cm F RIENDLY FACES 2016 Acrylic on linen 91 × 66 cm U NDERSTORY 2016 Acrylic on linen 71 × 81 cm C LIMBING UP THE FENCE 2016 Acrylic on linen 66 × 76 cm P SYCHE 2016 Acrylic on linen 76 × 66 cm P IXIE TEA 2016 Acrylic on canvas 70 × 60 cm E ARTHSCAPE 2016 Stabilised earth on linen 70 × 60 cm M AN WITH DOG 2016 Acrylic on linen 66 × 51 cm M E AND YOU 2016 Acrylic on canvas 51 × 61 cm N OCTURNAL DANCE 2016 Acrylic on canvas 50 × 60 cm T HE NIGHT WE LOST OUR MARBLES 2016 Acrylic on canvas 51 × 60 cm H OLY FOOL IN TREE 2016 Acrylic on wood 50 × 45 cm E BB AND FLOW 2016 Acrylic on linen 51 × 41 cm H OLY FOOL WITH BIRDS 2016 Acrylic on canvas 50 × 40 cm H OLY FOOL 2016 Acrylic on canvas 40 × 50 cm L IFEBOAT 2016 Acrylic on linen 51 × 40 cm A FFINITY 2016 Acrylic on linen 42 × 45 cm T HE ESCAPEE 2016 Acrylic on linen 36 × 46 cm E ACH OTHER 2016 Acrylic on wood 40 × 35 cm F AMILY TREE 2015 Acrylic on canvas 35 × 28 cm B EE BIRD 2016 Acrylic on linen 26 × 31 cm M ICHAEL LEUNIG— T HE NIGHT WE LOST OUR MARBLES Michael Leunig is an Australian cartoonist, writer, painter, philosopher and poet. -

Jesus Is the Gateway

theadvocate.tv SEPTEMBER 2015 In Conversation Australian author Naomi Reed talks “Not drowning, just waving: Six thoughts on serving without about The Plum Tree in the Desert. PAGE 12 >> sinking in your local church.” RORY SHINER PAGE 13 >> 4 Leaders’ mission Global Interaction and Baptist World Aid Australia in Malawi >> 5 Sexuality discussed Vose Seminary Principal speaks at seminar hosted by BCWA >> Photo: Baptist World Alliance Vibrancy and diversity left wonderful memories for delegates at the 21st Baptist World Congress held in Durban, South Africa. Jesus is the gateway Keith Jobberns Other Australian Baptists that count, from every nation and all 8 Bordered by love are members of Committees and tribes and peoples and tongues, Australia’s treatment of Commissions included John standing before the throne and refugees and asylum Over 2,500 delegates from more than 80 countries Beasy, Rod Benson, Bill Brown, before the Lamb, clothed in seekers >> came together for the 21st Baptist World Congress in Ross Clifford, Heather Coleman, white robes, and palm branches Durban, South Africa in July. Ken Edmonds, Brian Harris, were in their hands; and they John Hickey, Keith Jobberns, cry out with a loud voice, saying, Sue Peters, Frank Rees, “Salvation to our God who sits African Baptists hosted and the quality of the preaching. Mark Wilson and Stephen Vose. on the throne, and to the Lamb.”’ welcomed the delegates and the The sermon can viewed on the The 22nd Baptist World [Revelation 7:9-10] induction of Rev. Paul Msiza from BWA website. Congress will be held in Rio Preceding the BWA Congress Building South Africa as the President of Forums covered topics de Janeiro, Brazil in 2020. -

A Milestone for Baptists

theadvocate.tv APRIL 2018 IN CONVERSATION Nikola Lewis talks about what led her to the “Jesus’ desire is not to hide His face from us, but Girls’ Brigade Western Australia State Commissioner role, and the to be found. His desire is greater still: that we Girls’ Brigade 125 year celebrations. PAGE 12>> might abide in Him.” SIMON ELLIOTT 13>> 7 Reaching out Riverton Baptist Community Church reach out to new Australians >> 8 No place for violence Helping churches better respond to the issue of domestic violence >> Photo: Hadyn Siggins Pastor Karen Siggins’ appointment as the first female Chair of Council marks a milestone for Baptist Churches Western Australia. A milestone for Baptists 11 Humble servant Billy Graham preached an unchanging, old-fashioned The 122-year history of the Baptist Church in Western Australia is rich with milestones. Formed in message in new ways >> 1896 by four churches, Baptist Churches Western Australia (BCWA) has grown to see over 120 churches planted, a seminary founded and aged care established. In late 2017, another chapter was “A Council Member circumstances, will help me to Karen also shared her hope added to the history books with the since 2011, Karen brings an serve the Council well.” for BCWA. appointment of the first woman abundance of experience to When reflecting on what “I want my faith to make a Generous hearts to lead the Council of BCWA – the role along with a deep the future for BCWA might look difference today, while I wait for Lead Pastor of Lesmurdie Baptist connection to Baptist ministry like, Karen said some of the all the things that I hope for. -

Michael Leunig

Michael Leunig Bio Leunig, was born in East Melbourne, Victoria, grew up in the Melbourne suburb of Footscray and went to Maribyrnong High School before entering an arts degree at Monash University. His first cartoons appeared in the Monash University student newspaper, Lot's Wife, in the late 1960s. He was conscripted in the Vietnam War call-up, but he registered as a conscientious objector; in the event he was rejected on health grounds when it was revealed that he was deaf in one ear. After university Leunig enrolled at the Swinburne Film and Television School and then began his cartoon career. He has noted that he was at first interested in making documentaries. In the early 1970s his work appeared in the satirical magazine Nation Review, Woman's Day, London's Oz magazine and also various newspapers of that era. The main outlet for Leunig's work has been the daily Fairfax press, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age (Melbourne) newspapers published in Australia. In recent years he has focused mainly on political commentary, sometimes substituting his simple drawings with reproduced photographic images with speech balloons attached. The Australian Broadcasting Corporation has also provided airtime to Leunig to discuss his views on a range of political and philosophical issues. Leunig's drawings are done with a sparse, quavering line, usually in black and white with ink wash, the human characters always drawn with exaggerated features. This style served him well in his early years when he gained a loyal following for his quirky take on social issues. He also made increasingly frequent forays into a personal fantasy world of whimsy, featuring small figures with teapots balanced on their heads, grotesquely curled hair and many ducks. -

Love Your Global Neighbour

theadvocate.tv DECEMBER 2018 IN CONVERSATION Finding Faith duo, Andrew Tierney “Perhaps we need to keep challenging ourselves about the and Tim Dunfield talk about their passion for writing power of un-deciding to open ourselves to an even bigger songs of worship and their debut album. PAGE 12 >> decision – an even bigger ‘yes’.” SIMON ELLIOTT PAGE 13>> 3 Holy secularism Christmas is not what it used to be >> 4 Royal Commission Scheme provides support for childhood abuse >> Photo: Shane Burrell Risanya can grow enough food to feed her family and sell at the market for an income, thanks to the support of good neighbours in Australia. Love your global 10 Asia Bibi freed Christian mother released neighbour from Pakistan’s death row >> Baptist World Aid Australia, in conjunction with A Just Cause, has launched a efforts leading up to the next new report: The Global Neighbour Index. The report examines: Is Australia a good Federal Election, where Baptists global neighbour?, taking seriously Jesus’ call to “love your neighbour as yourself”. around the country will organise electorate forums using the report as a guide to converse Committed to Against its most-developed peers, government and the broader “It is not often that we get to with candidates. Australia was ranked 11th out of community to participate influence the policymakers of The index uses ten indicators being honest, 20 overall in a report that graded responsibly in seeking change. our nation in such a specific and to consider complex issues such transparent and each country’s contribution to Rather than considering the way personal way,” Perth delegate as inequality, poverty, climate the United Nation’s Sustainable SDGs are being implemented in Karen Wilson said. -

Download Thesisadobe

Celebrations for Personal and Collective Health and Wellbeing (Leunig 2001, p. 6) Julieanne Hilbers Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Education University of Technology, Sydney 2006 Certificate of Authorship/Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Candidate ________________________________________ ii I am grateful to Michael Leunig for permission to include a selection of his cartoons and poems in this thesis. Michael Leunig is an Australian cartoonist, poet and philosopher. He has been declared a national living treasure by the National Trust of Australia. Through his work Leunig often gives voice to the voiceless and uses the every day to explore the inner self and the wider world we live in. iii Undertaking this thesis has allowed me the space to listen, explore, reflect and to find voice. This journey has been supported, frustrated and celebrated by a number of people along the way. I extend my gratitude and thanks to: Judyth and Beverley for the inspiration and being such great ‘play’ mates. Everyone who gave took the time to share their thoughts and experiences. To my lovely friends who provided me with emotional support along the way.