Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bihar and West Bengal (Transfer of Territories) Act, 1956 ______Arrangement of Sections ______Chapter I Preliminary Sections 1

THE BIHAR AND WEST BENGAL (TRANSFER OF TERRITORIES) ACT, 1956 _______ ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS ________ CHAPTER I PRELIMINARY SECTIONS 1. Short title. 2. Definitions. PART II TRANSFER OF TERRITORIES 3. Transfer of territories from Bihar to West Bengal. 4. Amendment of First Schedule to the Constitution. PART III REPRESENTATION IN THE LEGISLATURES Council of States 5. Amendment of Fourth Schedule to the Constitution. 6. Bye-elections to fill vacancies in the Council of States. 7. Term of office of members of the Council of States. House of the people 8. Provision as to existing House of the People. Legislative Assemblies 9. Allocation of certain sitting members of the Bihar Legislative Assembly. 10. Duration of Legislative Assemblies of Bihar and West Bengal. Legislative Councils 11. Bihar Legislative Council. 12. West Bengal Legislative Council. Delimitation of Constituencies 13. Allocation of seats in the House of the People and assignment of seats to State Legislative Assemblies. 14. Modification of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Orders. 15. Determination of population of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. 16. Delimitation of constituencies. PART IV HIGH COURTS 17. Extension of jurisdiction of, and transfer of proceedings to, Calcutta High Court. 18. Right to appear in any proceedings transferred to Calcutta High Court. 19. Interpretation. 1 PART V AUTHORISATION OF EXPENDITURE SECTIONS 20. Appropriation of moneys for expenditure in transferred Appropriation Acts. 21. Distribution of revenues. PART VI APPORTIONMENT OF ASSETS AND LIABILITIES 22. Land and goods. 23. Treasury and bank balances. 24. Arrears of taxes. 25. Right to recover loans and advances. 26. Credits in certain funds. -

Women's Studies Paper-15 Geeta Mukherjee-Architect of the Women's

Women’s Studies Paper-15 Geeta Mukherjee-Architect of the Women’s Reservation Bill Module-16 PERSONAL DETAILS Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator Prof. Sumita Parmar Allahabad University, Allahabad Paper Coordinator Dr. Sabu George & CWDS, New Delhi Dr. Kumudini Pati Independent Researcher Associated with the Centre for Women’s Studies Allahabad University Content Writer/Author Dr. Kumudini Pati Independent Researcher Associated with the Centre for Women’s Studies Allahabad University Content Reviewer (CR) Prof. Sumita Parmar Allahabad University Language Editor (LE) Prof. Sumita Parmar Allahabad University, Allahabad DESCRIPTION OF MODULE Subject name Women’s Studies Paper name The stories the States Tell Module name/Title Geeta Mukherjee-Architect of the Women’s Reservation Bill Module ID Paper-15, Module-16 Pre-requisite Some awareness of the context of the Women’s Reservaton Bill Objectives To give the student an understanding of the history of the Women’s Reservation Bill and the long struggle that has gone into it. Keywords Quota, constitution, election, Lok Sabha, Parliament Geeta Mukherjee-Architect of the Women’s Reservation Bill Introduction A modest self-effacing personality but with a steely resolve to fight for the rights of women and the toiling people of India, Geeta Mukherjee, CPI M.P. from Panskura, West Bengal, remained active till the last day of her life. She was a member of the West Bengal Legislative Assembly from 1967 to 1977, winning the Panskura Purba Assembly seat 4 times in a row. She was elected a Member of Parliament for 7 terms, and remained active in parliamentary struggles for a period of 33 long years. -

Combating Trafficking of Women and Children in South Asia

CONTENTS COMBATING TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA Regional Synthesis Paper for Bangladesh, India, and Nepal APRIL 2003 This book was prepared by staff and consultants of the Asian Development Bank. The analyses and assessments contained herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asian Development Bank, or its Board of Directors or the governments they represent. The Asian Development Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this book and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. i CONTENTS CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS vii FOREWORD xi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY xiii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 UNDERSTANDING TRAFFICKING 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Defining Trafficking: The Debates 9 2.3 Nature and Extent of Trafficking of Women and Children in South Asia 18 2.4 Data Collection and Analysis 20 2.5 Conclusions 36 3 DYNAMICS OF TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA 39 3.1 Introduction 39 3.2 Links between Trafficking and Migration 40 3.3 Supply 43 3.4 Migration 63 3.5 Demand 67 3.6 Impacts of Trafficking 70 4 LEGAL FRAMEWORKS 73 4.1 Conceptual and Legal Frameworks 73 4.2 Crosscutting Issues 74 4.3 International Commitments 77 4.4 Regional and Subregional Initiatives 81 4.5 Bangladesh 86 4.6 India 97 4.7 Nepal 108 iii COMBATING TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN 5APPROACHES TO ADDRESSING TRAFFICKING 119 5.1 Stakeholders 119 5.2 Key Government Stakeholders 120 5.3 NGO Stakeholders and Networks of NGOs 128 5.4 Other Stakeholders 129 5.5 Antitrafficking Programs 132 5.6 Overall Findings 168 5.7 -

Institutional Approaches to the Rehabilitation of Survivors of Sex Trafficking in India and Nepal

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 6-1-2010 Rescued, Rehabilitated, Returned: Institutional Approaches to the Rehabilitation of Survivors of Sex Trafficking in India and Nepal Robynne A. Locke University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Locke, Robynne A., "Rescued, Rehabilitated, Returned: Institutional Approaches to the Rehabilitation of Survivors of Sex Trafficking in India and Nepal" (2010). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 378. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/378 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. RESCUED, REHABILITATED, RETURNED: INSTITUTIONAL APPROACHES TO THE REHABILITATION OF SURVIVORS OF SEX TRAFFICKING IN INDIA AND NEPAL __________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Social Sciences University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts __________ by Robynne A. Locke June 2010 Advisor: Richard Clemmer-Smith, Phd ©Copyright by Robynne A. Locke 2010 All Rights Reserved Author: Robynne A. Locke Title: Institutional Approaches to the Rehabilitation of Survivors of Trafficking in India and Nepal Advisor: Richard Clemmer-Smith Degree Date: June 2010 Abstract Despite participating in rehabilitation programs, many survivors of sex trafficking in India and Nepal are re-trafficked, ‘voluntarily’ re-enter the sex industry, or become traffickers or brothel managers themselves. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Salman Rushdie was on born 19 June 1947; he spent his childhood in Bombay but went to England at the age of fourteen to study at Rugby. He enrolled at Cambridge University to read history and afterwards lived mainly in Great Britain, before settling in the USA. After the Ayatollah Khomeini pronounced a fatwa against Rushdie and his novel The Satanic Verses (1988) in February 1989, Rushdie lived in hiding for several years but continued to write, produ- cing The Moor’s Last Sigh among other works. 2. The editions of the novels used are Midnight’s Children (MC) 1995, London: Vintage and The Moor’s Last Sigh (MLS) 1996, London: Vintage, and all page numbers in parentheses refer to these editions. 3. For a view similar to that of Brennan, see Conner 1997: 294–7. Teresa Heffernan likewise argues that Midnight’s Children is ‘from the outset sus- picious of the very model [...] of the modern nation’ (Heffernan 2000: 472); Thompson asserts that Rushdie eventually portrays the Indian nation as a ‘bad myth’ (Thompson 1995: 21). 4. See Bernd Hirsch 2001: 56–77. Heike Hartung focuses on exploring trends in western historiography in her study on the novels by Peter Ackroyd, Graham Swift and Salman Rushdie; she also briefly juxtaposes British and Indian his- toriography by contrasting the representation of the history of the Indian national movement in Percival Spear’s The Oxford History of India (1981) and Sumit Sarkar’s Modern India 1885–1947 (1989), without, however, making use of this material in her discussion of Rushdie’s novels (Hartung 2002: 235–41). -

Abortion Seekers: the Sex-Workers of Kolkata

“PROFESSIONAL” ABORTION SEEKERS: THE SEX-WORKERS OF KOLKATA Swati Ghosh Abortion Assessment Project - India First Published in October 2003 By Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes Survey No. 2804 & 2805 Aaram Society Road Vakola, Santacruz (East) Mumbai - 400 055 Tel. : 91-22-26147727 / 26132027 Fax : 22-26132039 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.cehat.org © CEHAT/HEALTHWATCH The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the collaborating organizations. Printed at Chintanakshar Grafics Mumbai 400 031 TABLE OF CONTENTS ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ PREFACE ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ v ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ ABSTRACT ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ vii ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ viii ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ I. INTRODUCTION ○○○○ 1 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ II. METHODOLOGY ○○○○ 3 ○○○○ III. OBSERVATION AND INFERENCE○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 5 A. ABORTION ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 5 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ B. NATURE OF ERVICES VAILABLE ○○○○○○○○○ S A 5 ○○○○○○○○○○ C. RATIONAL FOR CHOICE ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 6 ○○○○○○○ D. INDUCED ABORTION ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 6 E. N ON-SEEKERS OF ABORTION ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 9 IV. CHILDBIRTH ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 9 ○○○○○ A. FAMILY ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 10 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ V. CONTRACEPTIVES ○○○○○○○○○○○○ 11 A. TRADITIONAL MODES ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 11 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ B. MODERN METHODS ○○○○○○○○○○○ -

Chapter2 the Region and the Tribal People

CHAPTER2 THE REGION AND THE TRIBAL PEOPLE THE REGION / . West Bengal .......... West Bengal is a land of natural beauty, exquisite lyrical poetry and enthusiastic people. Situated in the east of India, West Bengal is stretches from the Himalayas in the north to the Bay of Bengal in the South. This state shares international boundaries with Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal. Hence it is a strategically important place. The State is interlocked by the other states like Sikkim, Assam, Orissa and Bihar. The river Hooghly and its tributaries, Mayurakshi, Damodar, Kangsabati and the Rupnarayan, enrich the soils of Bengal. The northern districts of West Bengal like Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri and Coach Bihar (in the Himalayas rariges) are watered by the rivers Tista, Torsa, Jaldhaka and Ranjit. From the northern places (feet of Himalayas) to the tropical forests of Sunderbans, West Bengal is a land of incessant beauty. The total area of West Bengal is 88, 752 square kilometers. There are 37,910 inhabited villages and 38,024 towns in West Bengal as per 1991 census. Census population of West Bengal is 8,02,21,171 (2001 ). The density of population as per 2001 census is 904. Sex ratio of West Bengal (females per thousand males) as per 2001 census is 934 and the literacy rate as per 2001 census is 69.22 per cent. The Scheduled Tribe population in West Bengal as per 1991 census is 38,08,760. The percentage of Scheduled Tribe population to total population as per 1991 census is 5.59. The District of Dakshin Dinajpur The district of Dakshin Dinajpur is situated in the northern part of the State of West Bengal. -

Sculptures of the Goddesses Manasā Discovered from Dakshin Dinajpur District of West Bengal: an Iconographic Study

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 10 Issue 4 Ser. I || April 2021 || PP 30-35 Sculptures of the Goddesses Manasā Discovered from Dakshin Dinajpur District of West Bengal: An Iconographic Study Dr Rajeswar Roy Assistant Professor of History M.U.C. Women’s College (Affiliated to The University of Burdwan) Rajbati, Purba-Bardhaman-713104 West Bengal, India ABSTRACT: The images of various sculptures of the goddess Manasā as soumya aspects of the mother goddess have been unearthed from various parts of Dakshin Dinajpur District of West Bengal during the early medieval period. Different types of sculptural forms of the goddess Manasā are seen sitting postures have been discovered from Dakshin Dinajpur District during the period of our study. The sculptors or the artists of Bengal skillfully sculpted to represent the images of the goddess Manasā as snake goddess, sometimes as Viṣahari’, sometimes as ‘Jagatgaurī’, sometimes as ‘Nāgeśvarī,’ or sometimes as ‘Siddhayoginī’. These artistic activities are considered as valuable resources in Bengal as well as in the entire world. KEYWORDS: Folk deity, Manasā, Sculptures, Snake goddess, Snake-hooded --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 20-03-2021 Date of Acceptance: 04-04-2021 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION Dakshin Dinajpur or South Dinajpur is a district in the state of West Bengal, India. It was created on 1st April 1992 by the division of the erstwhile West Dinajpur District and finally, the district was bifurcated into Uttar Dinajpur and Dakshin Dinajpur. Dakshin Dinajpur came into existence after the division of old West Dinajpur into North Dinajpur and South Dinajpur on 1st April, 1992. -

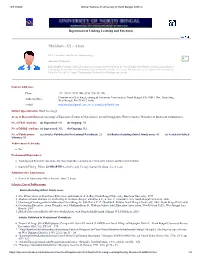

Mahbub - Ul - Alam

12/31/2020 Official Website of University of North Bengal (N.B.U.) ENLIGHTENMENT TO ERFECTION Department of Lifelong Learning and Extension Mahbub - Ul - Alam M.A. (Sociology and Social Anthropology) Associate Professor Life Member- Indian Adult Education Association and President of its West Bengal State Branch; Indian Association of Continuing Association; PaschimBangaVigyan Mancha, Founder Secretary, Balason Society for Improved Environment; Founder General Secretary, Chaitanyapur Shishutirtha Shikshaprasar Samiti Contact Addresses: Phone +91- 9434143574 (M), 0353-2581532 (R) Department of Lifelong Learning & Extension, University of North Bengal, P.O.-NBU, Dist. Darjeeling, Address(office) West Bengal, Pin-734013, India. e-Mail [email protected] , [email protected] Subject Specialization: Rural Sociology Areas of Research Interest: Sociology of Education (Formal & Non-formal), Social Demography, Women Studies, Minorities & Backward Communities. No. of Ph.D. students: (a) Supervised: Nil (b) Ongoing: Nil No. of M.Phil. students: (a) Supervised: NA (b) Ongoing: NA. No. of Publications: (a) Articles Published in Professional Periodicals: 25 (b) Books (Including Edited Jointly ones): 05 (c) Articles in Edited Volumes: 08 Achievement & Awards: No Professional Experiences: Teaching and Research experience for more than three decades as a University teacher and Research Scholar. Journals Editing: Editor, SAMBARTIKA, a half yearly Literary Journal for about eleven years. Administrative Experiences: Served as University Officer for more than 22 years. Selective List of Publications: Books (Including Edited Jointly ones): 1. New Thrust Areas of Population Education, with Sinha A. & A. Roy, North Bengal University, Burdwan University, 1997. 2. Medicinal Plants Suitable for Cultivating in Northern Bengal, with Das A.P., A. Sen, C. -

The Scalar Quantification of Ɔnek 'Many'

THE SCALAR QUANTIFICATION OF ƆNEK ‘MANY’ IN BANGLA TISTA BAGCHI University of Delhi The interpretation of so-called vague quantifiers such as many is, at the conceptual-intentional interface, a straightforward one, on par with standard quantifiers such as the universal every and (in frameworks that recognize existential quantifiers) the existential a/an or some. However, while vague quantifiers display the same scopal behavior as standard ones do (at least at a “thick” level) at this interface, their quantificational status remains quite distinct from that of the standard quantifiers: they do not straightforwardly relate to the domains or sets defined by the nominal component that they are merged with (Barwise & Cooper 1981, Szabolcsi 2010). The behavior of an analogue in Bangla, viz., the quantifier ɔnek ‘many’, is the central focus of this paper, given that it can be used in both count and noncount senses, unlike in Hindi, in which anek, like many, is exclusively [+count]. Vandiver (2011a) argues that many in English can be placed on a stationary scale of quantifiers, from a/an through all. This paper, on the other hand, argues that such an explanation fails to account for the distinctive behavior of ɔnek with respect to (i) scope interaction with negation (where ɔnek is always wider in scope than any negation that it might co-occur with), (ii) semantic interaction with the Bangla classifier –tạ /-khani (versus no classifier), (iii) its use as a comparative quantifier on occasion with emphatic focus. Furthermore, the lower threshold for [+count] ɔnek might be determined by the maximum “paucal” number, possibly varying across speakers. -

Proceedings of the Regional Workshop on IMPLEMENTATION of PCPNDT ACT 1994 Organised by Institute of Development Studies Kolkata

+- Proceedings of The Regional Workshop on IMPLEMENTATION OF PCPNDT ACT 1994 Organised By Institute Of Development Studies Kolkata Calcutta University Alipore Campus, 5th Floor 1,ReformatoryStreet Kolkata 700 027 At Auditorium, Swasthya Bhaban, GN-29, Sector-V, Salt Lake, Kolkata-700 091 On 1-2 February 2006 Sponsored by: National Commission for Women 1. Background The Pre-conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (PCPNDT) Act passed by the Indian Parliament came into force in 1994 for regulation and prevention of misuse of the diagnostic techniques. Subsequently, following a Supreme court order on its proper implementation certain amendments were made to the Act. The declining sex ratio in India particularly in the 0-6 year age group is a matter of grave concern. It was expected that proper implementation of the PCPNDT Act would check the pre-natal sex determination and elimination of the female foetus within the womb at least to some extent. However, although there has been ample time for implementing the Act, there is no sign that the decline in child sex ratio has been halted. Most states have set up the infrastructure prescribed in the Act, but this infrastructure is still to be effective. The problem of decline in sex ratio is very grave in Northern and Western India, particularly in those states that are said to be economically more developed. However, recent studies show that in certain parts of Eastern India too, the phenomenon has been fast catching up. For instance, the metropolitan areas of Kolkata show a steep decline in the sex ratio from 1991 to 2001 as far as the 0-6 year population group is concerned. -

Bii BHAORA 21, 1913 (SAKA) Hajf-An-Hour Discussion 530 Here

529 Finance (No.2) BiI BHAORA 21, 1913 (SAKA) HaJf-an-hour Discussion 530 National Commission for women SHRI JASWANT SINGH: PersonaUy I wasting the time of the House. A Jot of this discussed it with some people could be done in the Chamber. Let the HaIf here •.• (lntem.ptbns). In fact.lthink it can be an-Hour discussion go on. We have the time that tomorrow before the Private Members' to discuss it and let us discuss it and sort it Business and after the Private Members' out amongst ourselves. And come to a con Business, for however long it takes, we sit clusion. Meanwhile, let the time be utilised and finally dispose of the Anance Bill tomor for the Half-an-Hour discussion effectively. row itself. The Private Members' Business willbefinished atsixo·cIock.Acertainamount MR.DEPUTY SPEAKER : May t re of disposal would take place of speakers quest Shrimati Suseela GopaJan to com before the Private Members' Business starts mence her Half-an-Hour discussion? at 3. 30 or 3.45, whatever it is, and after it finishes at six o'clock. It wiD be much neater and tidierto dispose of the Anance Bill in that fashion. That would be my submission. 17_54 hrs. SHRt RANGARAJAN KUMARAMAN HALF-AN-HOUR DISCUSSION GALAM: There is also another problem, Sir. H tomorrow we are only going to take the National Commission for Women Finance Bill, then there are other Govern ment business also which are slated for (English) tomorrow. Keeping that in mind, we had agreed in the BAC that we have the BCCI discussion on Saturday morning.