2014 REVIEW from the Director

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Download Press

BIO - GRAPHY Tapestry Tapestry made its debut in Jordan Hall with a performance of Steve Reich’s Cristi Catt, soprano, has performed with Tehillim, deemed “a knockout” by The Boston Globe. The trademark of the leading early music groups including En- Boston-based vocal ensemble is combining medieval repertory and contem- semble PAN, Revels, Boston Camerata porary compositions in bold, conceptual programming. Critics hail their rich and La Donna Musicale. Her interest in the distinctive voices, their “technically spot-on singing” and their emotionally meeting points between medieval and folk charged performances. The LA Times writes “They sing beautifully separately traditions has led to research grants to Por- and together with a glistening tone and precise intonation” and The Cleve- tugal and France, and performances with land Plain Dealer describes Tapestry as “an ensemble that plants haunting HourGlass, Le Bon Vent, Blue Thread, and vibrations, old and new, in our ears.” Most recently, Tapestry has expanded their repertoire to include works of impression- ists including Debussy, Lili Boulanger and Vaughan Williams for a US tour in celebra- tion of the 100-year anniversary of World War One Armistice, culminating with a per- formance at the National Gallery in Wash- ington DC. Their newest program, Beyond Borders, builds on their impressionistic discoveries and expands to works of Duke Ellington, Samuel Barber, and Leonard Ber- nstein programmed with early music and folk songs. Concert appearances include the Utrecht Early Music and -

Moses and Frances Asch Collection, 1926-1986

Moses and Frances Asch Collection, 1926-1986 Cecilia Peterson, Greg Adams, Jeff Place, Stephanie Smith, Meghan Mullins, Clara Hines, Bianca Couture 2014 Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 600 Maryland Ave SW Washington, D.C. [email protected] https://www.folklife.si.edu/archive/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement note............................................................................................................ 3 Biographical/Historical note.............................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1942-1987 (bulk 1947-1987)........................................ 5 Series 2: Folkways Production, 1946-1987 (bulk 1950-1983).............................. 152 Series 3: Business Records, 1940-1987.............................................................. 477 Series 4: Woody Guthrie -

Steve Smith Biography 2020 Steve Smith's Drumming, While Always

Steve Smith Biography 2020 Steve Smith's drumming, while always decidedly modern, can best be described as a style that embodies the history of U.S. music. Originally drawn to the drums by hearing marching bands in parades as a child in his native Massachusetts, Smith began studying the drums at age nine, in 1963. After high school, Smith studied in Boston at the Berklee College of Music from 1972-76, where he had private lessons with both Gary Chaffee and Alan Dawson. His original love of rudimental parade band drumming is evident in his intricate solos. Likewise, his command of jazz, from New Orleans music, swing, big band, bebop, avant-garde to fusion, plus his rock drumming sensibilities and knowledge of rhythms from India allow him to push the boundaries of all styles to new heights. In 1976, Smith began his association with jazz-fusion by joining violinist Jean-Luc Ponty's group and recording the 1977 landmark fusion album Enigmatic Ocean. It was while touring with rocker Ronnie Montrose a year later that Smith was asked to join the popular rock band Journey which brought his playing to the attention of a rock audience. With Journey, Smith toured the world and recorded numerous successful albums including the immensely popular Escape (which includes the ubiquitous hit song “Don’t Stop Believin’”) and Frontiers, both of which garnered the band many Top 40 hits. Journey’s albums have sold in excess of 75 million copies worldwide to date. In 1985 Smith left Journey to pursue his original passion, jazz, and to continue his developing career as a session player, bandleader and educator. -

Table of Contents

1 •••I I Table of Contents Freebies! 3 Rock 55 New Spring Titles 3 R&B it Rap * Dance 59 Women's Spirituality * New Age 12 Gospel 60 Recovery 24 Blues 61 Women's Music *• Feminist Music 25 Jazz 62 Comedy 37 Classical 63 Ladyslipper Top 40 37 Spoken 65 African 38 Babyslipper Catalog 66 Arabic * Middle Eastern 39 "Mehn's Music' 70 Asian 39 Videos 72 Celtic * British Isles 40 Kids'Videos 76 European 43 Songbooks, Posters 77 Latin American _ 43 Jewelry, Books 78 Native American 44 Cards, T-Shirts 80 Jewish 46 Ordering Information 84 Reggae 47 Donor Discount Club 84 Country 48 Order Blank 85 Folk * Traditional 49 Artist Index 86 Art exhibit at Horace Williams House spurs bride to change reception plans By Jennifer Brett FROM OUR "CONTROVERSIAL- SUffWriter COVER ARTIST, When Julie Wyne became engaged, she and her fiance planned to hold (heir SUDIE RAKUSIN wedding reception at the historic Horace Williams House on Rosemary Street. The Sabbats Series Notecards sOk But a controversial art exhibit dis A spectacular set of 8 color notecards^^ played in the house prompted Wyne to reproductions of original oil paintings by Sudie change her plans and move the Feb. IS Rakusin. Each personifies one Sabbat and holds the reception to the Siena Hotel. symbols, phase of the moon, the feeling of the season, The exhibit, by Hillsborough artist what is growing and being harvested...against a Sudie Rakusin, includes paintings of background color of the corresponding chakra. The 8 scantily clad and bare-breasted women. Sabbats are Winter Solstice, Candelmas, Spring "I have no problem with the gallery Equinox, Beltane/May Eve, Summer Solstice, showing the paintings," Wyne told The Lammas, Autumn Equinox, and Hallomas. -

A “Journey” Through Band Agreements

Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 43 Number 2 Summer 2021 Article 4 Summer 2021 A “Journey” Through Band Agreements Jordan M. Whitford Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_comm_ent_law_journal Part of the Communications Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Jordan M. Whitford, A “Journey” Through Band Agreements, 43 HASTINGS COMM. & ENT. L.J. 189 (2021). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_comm_ent_law_journal/vol43/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A “Journey” Through Band Agreements By JORDAN WHITFORD* INTRODUCTION A “Journey” through band agreements reveals that it is not just about creating music. This paper will explain the ins and outs of band agreements, using the most recent lawsuit involving the band members of Journey along with other various disputes to demonstrate what issues can arise throughout a band’s lifespan. HISTORY OF JOURNEY JOURNEY ACCEPTED FAME, FORTUNE, AND BAND MEMBERS WITH “OPEN ARMS” The musical band Journey was formed in San Francisco, California in 1973 under the management of Herbie Herbert.1 Journey made their live debut at the Winterland -

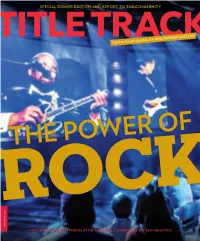

Special Donor Edition and Report to the Community

SPECIAL DONOR EDITION AND REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY TITLE TRACK THE ROCK & ROLL HALL OF FAME MEMBER MAGAZINE THE POWER OF ROCK DECEMBER 2018 DECEMBER NEW EXHIBITS AND EXPERIENCES AT THE ROCK HALL / CELEBRATING THE 2018 INDUCTEES W WELCOME Features AVIP 10 SUPPORTER A grant from the KeyBank Foun- dation provides free Rock Hall admission to local residents. ANEXPERIENCE 12 LIKENO OTHER The Connor Theater and the Power of Rock Experience are From the CEO exciting new attractions. Thanks to your support, 2018 has been a COMMITMENT fantastic year at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. 14 TOCLEVELAND The following pages provide a snapshot of the Chris and Sara Connor show their year; highlights include: belief in the city. The opening of our new Hall of Fame Gallery, presented by KeyBank, and the Power of Rock Experience in the Connor Theater. Departments 8 15 ON VIEW ENGAGEMENT Rock Hall Live! featured 80 days of live music 3 on our PNC outdoor stage. Stay Tuned explores Supporters Lydia ARTIST the intersection of Parker and Ed Special exhibits like Stay Tuned: Rock on VISITS TV and rock. Kleinman share their Musicians connect TV and the 2018 Inductee class featured 6 love of music. with their fans at the exhibition. ROCK U Rock Hall. Local teacher Stacy 16 There’s always something for everyone at Hubert knows the FINANCIAL 4 OVERVIEW the Rock Hall! It is with your support that we BACKSTAGE value of Rockin’ the Schools. Our 2017 report to can bring these elements together to engage, PASS the community and teach and inspire fans through the power of The 2018 Induction 7 thank you to our rock and roll. -

Steve Augeri

STEVE AUGERI Steve Augeri is an American rock singer best known for his work with Tall Stories, Tyketto, and Journey.[1] Career Drawing from a range of diverse musical influences to deliver a unique and personal take on the genre of melodic rock, Steve Augeri is an American rock singer best known as the lead vocalist for the rock group Journey from 1998 to 2006. Augeri recorded three albums during a successful eight-year tenure with the group that brought one of the world’s most accomplished rock groups back to the stage to perform for their millions of fans worldwide. He attributes his love and inspiration of music to his father, Joseph, and their many years of listening to Sinatra, R&B, Soul, and Country music on their Emerson clock radio. His grammar school music teacher, Fredrick Torregrossa, also had a direct influence by encouraging Augeri to develop and improve upon the potential of his voice and by casting him to sing Puccini’s "La Donna Mobile" in the school’s 4th grade musical. Initially studying woodwinds at New York City’s High School of Music and Art, Augeri switched to bassoon and soon discovered his love for classical music.[3] Attending, and then teaching at, French Woods Festival for the Performing Arts summer camp, he supervised children from ages 6–16 for their Rock Band classes which as he states, was surely the original “School of Rock.” When Augeri’s tuition check for college bounced, he returned home to start a rock and roll band. Working as a session vocalist, as well as bartending and waiting tables, it was not until 1984 when Augeri received his first break and was hired as background vocalist for one of the world’s most renowned hard rock guitarists, Michael Schenker of UFO and Scorpions fame. -

Guitarone Magazine

THE DEAD SET OUT ON SUMMER GETAWAY TOUR The Dead are coming together for their first Summer tour since Jerry Garcia's passing and will be joined on various dates of the tour by legendary musicians Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson, Steve Winwood, and celebrated Grateful Dead songwriter Robert Hunter. The Dead are kicking off the first leg of their Summer Getaway Tour at the sold-out Bonnaroo Festival in Tennessee on June 15 and will continue touring through early July. Steve Winwood will join the band from June 17-25, and Willie Nelson & Family will join the tour from June 27 through July 4; Nelson's final performance with The Dead will take place at his spectacular 4th of July picnic in Austin, TX. Tickets are on sale at dead.net as well as at Ticketmaster . The second leg of the Summer Getaway Tour will be co-headlined by the incomparable Bob Dylan, who will play prior to and sit in with The Dead. This pairing has not taken place since The Dead and Bob Dylan, along with his band, collaborated on a sold-out stadium tour in 1987. The second leg of the Summer Getaway Tour will be from July 29 through August 10. (Complete tour schedules follow.) The Dead are made up of Grateful Dead members Mickey Hart (percussion, drums, vocals), Bill Kreutzmann (drums), Phil Lesh (bass, vocals) and Bob Weir (guitar, vocals), whom are joined by keyboardists Jeff Chimenti and Rob Barraco, and lead guitarist Jimmy Herring. Also joining The Dead for the first time, injecting a soulful female voice, is Grammy-nominated singer Joan Osborne. -

1 This Chronology Includes All of the Core Repertoire Appearing in Each

New Model Music Curriculum Appendix 2 – Chronology: Repertoire in Context This chronology includes all of the Core Repertoire appearing in each Key Stage and Year as well as additional repertoire appropriate to learning based on the Model Music Curriculum. It is presented in chronological order of the year in which the piece or song was written and grouped by era in order to help pupils develop their knowledge of different musical periods and styles. Traditional Folk and World music can be used to enhance and deliver aspects of the Model Music Curriculum. They are especially useful in developing aural awareness, and to help pupils appreciate and understand music from different traditions. Items in bold indicate Foundation Listening repertoire that appears within the Model Music Curriculum. The suggested curriculum year is given as a guideline for its use. Early Period Year Composer Title of Piece Curriculum Source Year 1000 Anon Orientis Partibus 8 Orientis partibus - YouTube Medieval mystery play 1130 Hildegard Hortus Deliciarum 7 Hildegard von Bingen - Hortus Deliciarum - YouTube 1140 Hildegard O Euchari 4 ABRSM Classical 100 1200 Anon Ductias 1 & 2 7 Ductia #1 from the 13th century for two voices - YouTube Ductia #2 from the 13th century for two voices - YouTube 1225 Anon Miri it is while 7 Mediaeval English Folk Song - Miri It Is While Sumer Ilast sumer ilast - YouTube 1250 Anon Sumer is Icumen In 7 Sumer is Icumen in (The Hilliard Ensemble) - YouTube Renaissance Period Year Composer Title of Piece Curriculum Source Year 1551 Susato -

Rock, Rhythm, & Soul

ARCHIVES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN MUSIC AND CULTURE liner notes NO. 13 / WINTER 2008-2009 Rock, Rhythm, & Soul: The Black Roots of Popular Music liner notes final 031009.indd 1 3/10/09 5:37:14 PM aaamc mission From the Desk of the Director The AAAMC is devoted to the collection, preservation, and dissemination of materials for the purpose of research and I write this column on January music critics and scholars to discuss study of African American 20, 2009, the day our country and the socio-political history, musical music and culture. the world witnessed history being developments, and the future of black www.indiana.edu/~aaamc made with the swearing-in of the 44th rock musicians and their music. The President of the United States, Barack AAAMC will host one panel followed Obama, the first African American by a light reception on the Friday elected to the nation’s highest office. afternoon of the conference and two Table of Contents The slogan “Yes We Can” that ushered panels on Saturday. The tentative in a new vision for America also fulfills titles and order of the three panels are From the Desk of part of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “What Is Rock: Conceptualization and the Director ......................................2 dream for a different America—one Cultural Origins of Black Rock,” “The that embraces all of its people and Politics of Rock: Race, Class, Gender, Featured Collection: judges them by the content of their Generation,” and “The Face of Rock Patricia Turner ................................4 character rather than the color or their in the 21st Century.” In conjunction skin. -

Neal Schon Played We Captured Some Great Energy That When the Adventure Starts

NOVEMBER 2012 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM NOVEMBER 2012 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM MUSICIAN How is this solo album unique? How important is melody? TOOLS OF THE TRADE Usually when I make an album I love it I’m always thinking about melody. Once I for a moment and then put it away. This have that melodic structure in my head, that’s has staying power the others didn’t have. when I start messing around with it. That’s For most of The Calling, Neal Schon played We captured some great energy that when the adventure starts. If you don’t have custom Paul Reed Smith guitars—all single- translated into different styles of music. a strong melody you don’t have anything. cutaways, some with 22-fret necks and It sounds more off-the-cuff. The structure When it comes to instrumental records, a couple with 24. “I had them set up with is there but there’s looseness within that there are lots of great guitarists who could Roland GK synth pickups and a Fernandes structure—it’s a controlled looseness. run rings around me. For me it’s more about Sustainer,” says Schon. He also used a Roland expression and having style. There’s a lot of Fantom single-space rack synthesizer module Describe the recording process. blues and R&B roots in my playing. When I designed for keyboards but reconfigured for Everything was dictated by guitar and first started I was listening to a lot of Aretha guitar. “I used a lot of synth on the album,” drums. -

Greatest Hits on Earth Returning to the Hanover Theatre

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Greatest Hits on Earth Returning to The Hanover Theatre Worcester, Mass. (May 17, 2016) The former members and musicians who played with Boston, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Journey, The Storm and Rare Earth are coming to Worcester for one night this fall. Symply Fargone Productions and Greatest Hits on Earth – Live® present Rock & Pop Masters®, coming to The Hanover Theatre for the Performing Arts on Saturday, September 24 at 8 p.m. Tickets are on sale now to members. Tickets go on sale to the public on Tuesday, May 24. In his younger days, Randall Hall attended the infamous Monkees tour where the legendary Jimi Hendrix was the opening act. While most attendees were busy booing Hendrix off stage, the former Monkees fan was entranced and decided heavy riffing was the way to go. Adding in the Southern flavor of the Allman Brothers, Randall formed his first band, Running Easy, in 1971. In 1987, Randall was asked to take the place of Allen Collins in Lynyrd Skynyrd after Collins’ paralyzing car accident. He remained a member of the band until 1994. Fran Cosmo exploded onto the rock scene when he took over for Brad Delp as the lead singer of Boston in 1992. Fran was featured as the lead vocalist on the “Walk On” album, which sold over one million copies worldwide. Prior to his success as the lead singer of Boston, he was the lead singer and song co-writer for both “Orion the Hunter” and Barry Goundreau albums. Fran Cosmo is known for his high-energy and outstanding vocal range on Boston songs that very few, if any, can perform.