The Role of Food in Kubrick's Lolita, a Clockwork Orange and Barry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Kubrick's Kelley O'brien University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2018 "He Didn't Mean It": What Kubrick's Kelley O'Brien University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation O'Brien, Kelley, ""He Didn't Mean It": What Kubrick's" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7204 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “He Didn‟t Mean It”: What Kubrick‟s The Shining Can Teach Us About Domestic Violence by Kelley O‟Brien A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts With a concentration in Humanities Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Daniel Belgrad, Ph.D. Maria Cizmic, Ph.D. Amy Rust Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 8, 2018 Keywords: Patriarchy, Feminism, Gender Politics, Horror, American 1970s Copyright © 2018, Kelley O‟Brien Dedication I dedicate this thesis project to my mother, Terri O‟Brien. Thank you for always supporting my dreams and for your years of advocacy in the fight to end violence against women. I could not have done this without you. Acknowledgments First I‟d like to express my gratitude to my thesis advisor Dr. -

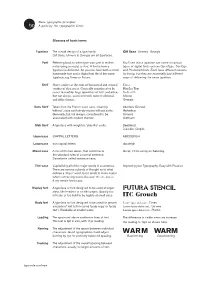

WARM WARM Kerning by Eye for Perfectly Balanced Spacing

Basic typographic principles: A guide by The Typographic Circle Glossary of basic terms Typeface The overall design of a type family Gill Sans Univers Georgia Gill Sans, Univers & Georgia are all typefaces. Font Referring back to when type was cast in molten You’ll see that a typeface can come in various metal using a mould, or font. A font is how a types of digital font; such as OpenType, TrueType typeface is delivered. So you can have both a metal and Postscript fonts. Each have different reasons handmade font and a digital font file of the same for being, but they are essentially just different typeface, e.g Times or Futura. ways of delivering the same typeface. Serif Short strokes at the ends of horizontal and vertical Times strokes of characters. Generally considered to be Hoefler Text easier to read for large quantities of text, and often, Baskerville but not always, associated with more traditional Minion and older themes. Georgia Sans Serif Taken from the French word sans, meaning Akzidenz Grotesk ‘without’, sans serif simply means without serifs. Helvetica Generally, but not always, considered to be Univers associated with modern themes. Gotham Slab Serif A typeface with weightier, ‘slab-like’ serifs. Rockwell Lubalin Graph Uppercase CAPITAL LETTERS ABCDEFGH Lowercase non-capital letters abcdefgh Mixed-case A mix of the two above, that conforms to Great, it’ll be sunny on Saturday. the standard rules of a normal sentence. Sometimes called sentence-case. Title-case Capitalising all of the major words in a sentence. Improving your Typography: Easy with Practice There are various schools of thought as to what defines a ‘major’ word, but it tends to looks neater when connecting words like and, the, to, but, is & my remain lowercase. -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

Stanley Kubrick's 18Th Century

Stanley Kubrick’s 18th Century: Painting in Motion and Barry Lyndon as an Enlightenment Gallery Alysse Peery Abstract The only period piece by famed Stanley Kubrick, Barry Lyndon, was a 1975 box office flop, as well as the director’s magnum opus. Perhaps one of the most sumptuous and exquisite examples of cinematography to date, this picaresque film effectively recreates the Age of the Enlightenment not merely through facts or events, but in visual aesthetics. Like exploring the past in a museum exhibit, the film has a painterly quality harkening back to the old masters. The major artistic movements that reigned throughout the setting of the story dominate the manner in which Barry Lyndon tells its tale with Kubrick’s legendary eye for detail. Through visual understanding, the once obscure novel by William Makepeace Thackeray becomes a captivating window into the past in a manner similar to the paintings it emulates. In 1975, the famed and monumental director Stanley Kubrick released his one and only box-office flop. A film described as a “coffee table film”, it was his only period piece, based on an obscure novel by William Makepeace Thackeray (Patterson). Ironically, his most forgotten work is now considered his magnum opus by critics, and a complete masterwork of cinematography (BFI, “Art”). A remarkable example of the historical costume drama, it enchants the viewer in a meticulously crafted vision of the Georgian Era. Stanley Kubrick’s film Barry Lyndon encapsulates the painting, aesthetics, and overall feel of the 18th century in such a manner to transform the film into a sort of gallery of period art and society. -

A Clockwork Orange and Stanley Kubrick’S Film Adaptations

2016-2017 A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Linguistics and Literature: English & Dutch THE TRUTH BETWEEN THE LINES A Comparative Analysis of Unreliable Narration in Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange and Stanley Kubrick’s Film Adaptations Name: Isaura Vanden Berghe Student number: 01304811 Supervisor: Marco Caracciolo ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my master’s dissertation advisor Assistant Professor of English and Literary Theory, Marco Caracciolo of the Department of Literary Studies at the University of Ghent. Whenever I needed guidance or had a question about my research or writing, Prof. Caracciolo was always quick to respond, steering me in the right direction whenever he thought I needed it. Then, I must also express my very profound gratitude to my parents and to my brother for providing me with continuous encouragement and unfailing support throughout my years of study and through the process of writing and researching this dissertation. This accomplishment would not have been possible without them. Thank you. TABLE OF CONTENT INTRODUCTION 1 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 5 THEORY OF UNRELIABLE NARRATION 5 UNRELIABLE NARRATION IN FILM 9 LOLITA 12 LOLITA: THE NOVEL (1955) 12 IN HUMBERT HUMBERT’S DEFENSE: A SUMMARY 12 UNRELIABLE NARRATION IN THE NOVEL 15 LOLITA: THE FILM (1962) 35 STANLEY KUBRICK AND ‘CINEMIZING’ THE NOVEL 35 UNRELIABLE NARRATION IN THE FILM 36 A CLOCKWORK ORANGE 47 A CLOCKWORK ORANGE: THE NOVEL (1962) 47 ALEX’S ULTRA-VIOLENT RETELLING: A SUMMARY 47 UNRELIABLE NARRATION IN THE NOVEL 50 A CLOCKWORK ORANGE: THE FILM (1972) 63 STANLEY KUBRICK’S ADAPTATION 63 UNRELIABLE NARRATION IN THE FILM 64 CONCLUSION 75 REFERENCES APPENDIX A APPENDIX B APPENDIX C INTRODUCTION In 2011, Mark Jacobs launched a campaign ad for a new fragrance of his, called ‘Oh, Lola!’1. -

The New Hollywood Films

The New Hollywood Films The following is a chronological list of those films that are generally considered to be "New Hollywood" productions. Shadows (1959) d John Cassavetes First independent American Film. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) d. Mike Nichols Bonnie and Clyde (1967) d. Arthur Penn The Graduate (1967) d. Mike Nichols In Cold Blood (1967) d. Richard Brooks The Dirty Dozen (1967) d. Robert Aldrich Dont Look Back (1967) d. D.A. Pennebaker Point Blank (1967) d. John Boorman Coogan's Bluff (1968) – d. Don Siegel Greetings (1968) d. Brian De Palma 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) d. Stanley Kubrick Planet of the Apes (1968) d. Franklin J. Schaffner Petulia (1968) d. Richard Lester Rosemary's Baby (1968) – d. Roman Polanski The Producers (1968) d. Mel Brooks Bullitt (1968) d. Peter Yates Night of the Living Dead (1968) – d. George Romero Head (1968) d. Bob Rafelson Alice's Restaurant (1969) d. Arthur Penn Easy Rider (1969) d. Dennis Hopper Medium Cool (1969) d. Haskell Wexler Midnight Cowboy (1969) d. John Schlesinger The Rain People (1969) – d. Francis Ford Coppola Take the Money and Run (1969) d. Woody Allen The Wild Bunch (1969) d. Sam Peckinpah Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) d. Paul Mazursky Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (1969) d. George Roy Hill They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969) – d. Sydney Pollack Alex in Wonderland (1970) d. Paul Mazursky Catch-22 (1970) d. Mike Nichols MASH (1970) d. Robert Altman Love Story (1970) d. Arthur Hiller Airport (1970) d. George Seaton The Strawberry Statement (1970) d. -

Films Winning 4 Or More Awards Without Winning Best Picture

FILMS WINNING 4 OR MORE AWARDS WITHOUT WINNING BEST PICTURE Best Picture winner indicated by brackets Highlighted film titles were not nominated in the Best Picture category [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] 8 AWARDS Cabaret, Allied Artists, 1972. [The Godfather] 7 AWARDS Gravity, Warner Bros., 2013. [12 Years a Slave] 6 AWARDS A Place in the Sun, Paramount, 1951. [An American in Paris] Star Wars, 20th Century-Fox, 1977 (plus 1 Special Achievement Award). [Annie Hall] Mad Max: Fury Road, Warner Bros., 2015 [Spotlight] 5 AWARDS Wilson, 20th Century-Fox, 1944. [Going My Way] The Bad and the Beautiful, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1952. [The Greatest Show on Earth] The King and I, 20th Century-Fox, 1956. [Around the World in 80 Days] Mary Poppins, Buena Vista Distribution Company, 1964. [My Fair Lady] Doctor Zhivago, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1965. [The Sound of Music] Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Warner Bros., 1966. [A Man for All Seasons] Saving Private Ryan, DreamWorks, 1998. [Shakespeare in Love] The Aviator, Miramax, Initial Entertainment Group and Warner Bros., 2004. [Million Dollar Baby] Hugo, Paramount, 2011. [The Artist] 4 AWARDS The Informer, RKO Radio, 1935. [Mutiny on the Bounty] Anthony Adverse, Warner Bros., 1936. [The Great Ziegfeld] The Song of Bernadette, 20th Century-Fox, 1943. [Casablanca] The Heiress, Paramount, 1949. [All the King’s Men] A Streetcar Named Desire, Warner Bros., 1951. [An American in Paris] High Noon, United Artists, 1952. [The Greatest Show on Earth] Sayonara, Warner Bros., 1957. [The Bridge on the River Kwai] Spartacus, Universal-International, 1960. [The Apartment] Cleopatra, 20th Century-Fox, 1963. -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY Aspects of Postmodernism in Anthony Burgess

MASARYK UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English Language and Literature Aspects of Postmodernism in Anthony Burgess’ Novels Diploma thesis Brno 2011 Supervisor: PhDr. Pavel Doležel, Csc. Author: Bc. Radka Mikulaková Bibliographic note Mikulaková, Radka. Aspects of Postmodernism in Anthony Burgess’ novels. Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, Department of English Language and Literature, 2011. Supervisor Pavel Doležel. Anotace Diplomová práce Aspekty postmodernismu v románech Anthony Burgesse pojednává o literárním postmodernismu v románech Anthony Burgesse. Jmenovitě v románech A Clockwork Orange, The Wanting Seed a 1985, které jsou tematicky propojeny autorovou teorií vývoje moderní společnosti. Práce je rozdělena do tří základních oddílů. První část shrnuje základní literárněvědné přístupy k samotnému pojmu postmodernismus a stanovuje tak teoretická východiska k dalším oddílům práce. V následující části jsou výše uvedené romány podrobeny literární analýze z hlediska teorie fikčních světů a závěrem je stěžejní téma románů, Burgessova teorie cyklického vývoje společnosti, porovnáno a zkoumáno z hlediska dobových filozoficko-sociologických tendencí. Annotation Diploma thesis Aspects of Postmodernism in Anthony Burgess’ Novels deals with literary postmodernism in Anthony Burgess‟ novels, i.e. in A Clockwork Orange, The Wanting Seed and 1985, which are thematically connected by author‟s theory of the development of contemporary society. Thesis is divided into three chapters. The first chapter deals with basic scientific approaches to the term postmodernism and thus defines a theoretical basis for other chapters. In the following part the three of Burgess‟ novels are analyzed from the perspective of fictional semantics and, finally, the main theme of these Burgess‟ novels, a cyclic theory of human development, is compared and contrasted with the then socio-philosophical tendencies. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

March 30, 2010 (XX:11) Stanley Kubrick, the SHINING (1980, 146 Min)

March 30, 2010 (XX:11) Stanley Kubrick, THE SHINING (1980, 146 min) Directed by Jules Dassin Directed by Stanley Kubrick Based on the novel by Stephen King Original Music by Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind Cinematography by John Alcott Steadycam operator…Garrett Brown Jack Nicholson...Jack Torrance Shelley Duvall...Wendy Torrance Danny Lloyd...Danny Torrance Scatman Crothers...Dick Hallorann Barry Nelson...Stuart Ullman Joe Turkel...Lloyd the Bartender Lia Beldam…young woman in bath Billie Gibson…old woman in bath Anne Jackson…doctor STANLEY KUBRICK (26 July 1928, New York City, New York, USA—7 March 1999, Harpenden, Hertfordshire, England, UK, natural causes) directed 16, wrote 12, produced 11 and shot 5 films: Eyes Wide Shut (1999), Full Metal Jacket (1987), The Shining Lyndon (1976); Nominated Oscar: Best Writing, Screenplay Based (1980), Barry Lyndon (1975), A Clockwork Orange (1971), 2001: A on Material from Another Medium- Full Metal Jacket (1988). Space Odyssey (1968), Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), Lolita (1962), Spartacus STEPHEN KING (21 September 1947, Portland, Maine) is a hugely (1960), Paths of Glory (1957), The Killing (1956), Killer's Kiss prolific writer of fiction. Some of his books are Salem's Lot (1974), (1955), The Seafarers (1953), Fear and Desire (1953), Day of the Black House (2001), Carrie (1974), Christine (1983), The Dark Fight (1951), Flying Padre: An RKO-Pathe Screenliner (1951). Half (1989), The Dark Tower (2003), Dark Tower: The Song of Won Oscar: Best Effects, Special Visual Effects- 2001: A Space Susannah (2003), The Dark Tower: The Drawing of the Three Odyssey (1969); Nominated Oscar: Best Writing, Screenplay Based (2003), The Dark Tower: The Gunslinger (2003), The Dark Tower: on Material from Another Medium- Dr. -

George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5s2006kz No online items George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042 Finding aid prepared by Hilda Bohem; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 November 2. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections George P. Johnson Negro Film LSC.1042 1 Collection LSC.1042 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: George P. Johnson Negro Film collection Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1042 Physical Description: 35.5 Linear Feet(71 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1916-1977 Abstract: George Perry Johnson (1885-1977) was a writer, producer, and distributor for the Lincoln Motion Picture Company (1916-23). After the company closed, he established and ran the Pacific Coast News Bureau for the dissemination of Negro news of national importance (1923-27). He started the Negro in film collection about the time he started working for Lincoln. The collection consists of newspaper clippings, photographs, publicity material, posters, correspondence, and business records related to early Black film companies, Black films, films with Black casts, and Black musicians, sports figures and entertainers. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Portions of this collection are available on microfilm (12 reels) in UCLA Library Special Collections. -

The Glenville Mercury Number 24 Glenville State College

The Glenville Mercury Number 24 Glenville State College. Glenville. WV 26351 Wednada)" March 20, 1985 r Spring Graduates Announced Dr. Bruce Flack, Vice 7 -9. President for Academic Karen Lynn Hawkins, Affairs, has released a Pleasants, Elem. 1-6; tentative list of May Ranay Lynn Hibbs, graduates. Wood, Elem. 1-6; Early Students anticipating Ed. N-K; Diana Lynn Bachelor of Arts degrees Hilton, Jackson, Elem. 1- in Education include the 6/ Ear lyE d. N -K; following: Michael Allen Holcomb, Regi.na G. Bailes, Webster, Soc. Stu. Nicholas, Elem. 1- Compo 7-12; Leesa Kay 6/Men . Retard . K- Holder, Belpre, OH, 12/Phys.Ed. 4-8; ·Susan Music Compo K-12/ Ann Ballengee, Fayette, Phys. Ed. K-12. Art Compo K-12/Phys. Linda Frame Justice, Ed. K-12; Judith Ann Nicholas, Elem. 1-6; - Shown above are members of the cut Barnett, Nicholas, Elem. Brenda Lee Kinnison, 1-6; Don Lavier Bell, Pocahontas, Art 7- "Crimes of Heart" To Open March 21 Dillsburg, PA, Phys. Ed. 12/ Phys. Ed. K-12; The Pulitzer Prize Supporting Actress of Gauley Bridge, West K-12/Safety Ed. 7-12; Elizabeth Grove Lathey .. winning play Crimes of award for her role in The Virginia. Guy Franklin Boggs, Jr., Wood, Elem. 1-6/ Early the Heart hits the stage Music Man. She Senior Michael Dot Wood, Music Compo K- Ed. N-K/Math. 4-8; this week. Show dates graduated from Central son, majoring in English 12. Maria Lynn Lothes, are March 21 , 22, and 23 Preston Senior High and minoring in History Carol Lynn Thomas Randolph, Elem.