(Re)Creation Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Resume-Aaliyah

Aaliyah Muhammad Sag-Eligible • Height: 5’1 Address: 5633 Hunters Bend Ln Dallas, Tx 75249 • Weight: 120lbs Email: [email protected] • Hair: Black Mobile: (972) 765 0564 • Eyes: Brown • Size: 4 TV/Web Series Cruel Summer 2021 Renee FreeForm SKAM Austin 2019 Zoya Facebook Watch SKAM Austin 2018 Zoya Facebook Watch Asia’s Hip Hop Cooking 2009 Co-star YouTube FILM Infamous 2020 Emma Joshua Caldwell Caged Birds 2019 Keyaira Fred Leach Echos 2018 Emily Jordan Price The Little Voice 2017 Kendra Sweet Chariot Prod. Carter High 2015 Tammy Arthur Muhammad First Impression 2013 Teenager Arthur Muhammad Hiding In Plain Sight 2012 Kendra M. Legend Brown Black Angels 2010 Young Nicole Arthur Muhammad Commercial Chuck E. Cheese 2020 Dancer Industrial PW Pregnancy 2019 Patient PW Baptist Church Medical City Spine 2019 Daughter NBC Educational 2019 Raima Industrial Texas Voters 2018 Teen AMS Pictures Jr. Achievement 2017 Runner Cameron Gott VOICE OVER PW Pregnancy Promo 2019 PW Baptist Church Rescue for Social Change PSA 2012 KD Brown THEATRE Good Kids 2017 Brianna Liz Bayshore Semester Showcase 2016 3 Diff. Characters Amy Jackson Deadly Field Trip 2014 Ms. Hemphill Mrs. Russell Kwanzaa 2004 Dancer Lancaster Theatre Hosting The Black Owned Tour 2021 Interview 93 Supreme Catch The Beat 2018 Host Latoya Muhammad A Taste of the NFL 2017 Interview Parlay Ticket Celebrity Basketball Game 2017 Interview Parlay Ticket Parlay Ticket 2017 Co-Host Parlay Ticket A Night For The Stars 2016 Interview Parlay Ticket Celebrity Interviews 2016 Co-Host STI740 -

Serena Williams' Wedding “Iconic”

HAPPY Presorted Standard THANKSGIVING ! U.S. Postage Paid Austin, Texas Permit No. 01949 TPA TEXAS PUBLISHERS www.TheAustinVillager.com ASSOCIATION This paper can be recycled Vol. 45 No. 27 Phone: 512-476-0082 Email: [email protected] November 24, 2017 Serena Williams’ Jennifer Hudson INSIDE Wedding “Iconic” Obtains Protection And Not Just Because Order Against Beyoncé Was There by: MEAGAN FREDETTE Ex-Fiancé Vocal powerhouse by: The Associated Press and TV legend RAPPIN’ passes at 86. Tommy Wyatt See DELLA This is the Page 2 Holiday Season It is the Holiday Season again. This is one year that I cannot say, “Where did the time go?” That is High profile actresses because I vividly speak out on remember the last year sexual harassment. day by day. There was a See HIGHER time when I was not sure Page 3 that we would make it, business wise, past the summer. I can truly say that last summer was the toughest one that I have had since I have been in business. But, because of FILE – In this Feb. 8, 2009 file photo, Jennifer Inflated voter turnout our many friends and Hudson, left, and David Otunga arrive at the 51st shakes up Wilco’s supporters, we survived. Annual Grammy Awards in Los Angeles. Hudson political landscape. Now we are trying to has obtained an order of protection against See DEMOCRATIC make it to the New Year. Serena Williams & Alexis Ohanian Otunga. Police in suburban Chicago say Otunga Page 6 So, I am excited to say [Photo courtesy Alexis Ohanian / www.instagram.com] was removed from the couple’s home in Burr Happy Thanksgiving and Ridge, Illinois, Thursday night after being notified Trump Says He NEW ORLEANS, LA - Internationally ranked no. -

Julie Andem - SKAM

Julie Andem - SKAM The SKAM books are the original scripts of the worldwide hit web drama series of the same name, just as they were written. Each SKAM book contains one of the four seasons that aired between 2015 and 2017. The scripts have never recorded scenes, lines that were later cut, newly written prologues and epilogues, and Julie Andem’s own comments and unique mind maps. Get ready to get to know the characters Eva, Noora, Isak and Sana like never before. Julie Andem SKAM Season 1: Eva SALOMONSSON AGENCY Julie Andem Salomonsson Agency was founded in 2000. Today, the agency has twenty-four employees SKAM Season 2: Noora and represents around fifty Nordic authors of literary fiction, crime fiction, children’s fiction Julie Andem and narrative nonfiction, as well as a select list of screenwriters. SKAM Season 3: Isak www.salomonssonagency.se Julie Andem SKAM Season 4: Sana Last updated September 06, 2019 at booksfromnorway.com, a website providing you with information in English about Norwegian literature. Julie Andem SKAM Season 1: Eva The SKAM books are the original scripts of the worldwide hit web drama series of the same name, just as they were written. Each SKAM book contains one of the four seasons that aired between 2015 and 2017. The scripts have never recorded scenes, lines that were later cut, newly written prologues and epilogues, and Julie Andem’s own comments and unique mind maps. Armada 2018 206 pages Original title: SKAM Sesong 1: Eva SKAM Season 1: Eva follows the main character Eva Kviig Mohn as she starts high ISBN: 9788293687009 school. -

Report the Role of the Arts in the Digital Transformation This Report Is

Report from the EU H2020 Research and Innovation Project Artsformation: Mobilising the Arts for an Inclusive Digital Transformation The Role of the Arts in the Digital Transformation Ana Alacovska, Peter Booth, Christian Fieseler This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 870726. Report of the EU H2020 Research Project Artsformation: Mobilising the Arts for an Inclusive Digital Transformation State-of-the-Art: The Role of the Arts in the Digital Transformation Ana Alacovska1, Peter Booth2, and Christian Fieseler2 1 Copenhagen Business School 2 BI Norwegian Business School This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 870726 Suggested citation: Alacovska, A., Booth, P. and Fieseler, C. (2020) The Role of the Arts in the Digital Transformation. Artsformation Report Series, available at: (SSRN), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3715612 About Artsformation: Artsformation is a Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation project that explores the intersection between arts, society and technology Arts- formation aims to understand, analyse, and promote the ways in which the arts can reinforce the social, cultural, economic, and political benefits of the digital transformation. Artsformation strives to support and be part of the process of making our communities resilient and adaptive in the 4th Industrial Revolution through research, innovation and applied artistic practice. To this end, the project organizes arts exhibitions, host artist assemblies, creates new artistic methods to impact the digital transformation positively and reviews the scholarly and practi- cal state of the arts. -

SKAM Season 4: Sana

Julie Andem SKAM Season 4: Sana The SKAM books are the original scripts of the worldwide hit web drama series of the same name, just as they were written. Each SKAM book contains one of the four seasons that aired between 2015 and 2017. The scripts have never recorded scenes, lines that were later cut, newly written prologues and epilogues, and Julie Andem’s own comments and unique mind maps. Armada 2018 2010 pages Original title: SKAM Sesong 4: Sana SKAM Season 4: Sana gives the leading role to Sana Bakkoush, who guides the reader ISBN: 9788293687030 through tough contemporary issues like cyberbullying and religion’s impact on love and friendship. Sana, a Muslim, has her beliefs tested when she falls for Yousef, who FOREIGN RIGHTS doesn’t share her religion. But she also has to navigate clashes between her brother and Salomonsson Agency her friends, and the malicious actions of Sara. Sana creates an Instagram hate account, Götgatan 27 but later confesses. The final episode of the season, which switches between characters, 116 21 Stockholm deals with parental depression, rejection, jealousy, friendship, abandonment, and Tel:+46 8223211 [email protected] mutual support. www.salomonssonagency.se The SKAM books are the ultimate key to the universe that absorbed an entire RIGHTS SOLD TO generation of viewers. Get ready to get to know Eva, Noora, Isak and Sana like never See updated rights here before. OTHER TITLES SKAM Season 4: Sana Julie Andem SKAM Season 3: Isak SKAM Season 2: Noora SKAM Season 1: Eva Julie Andem (b. 1982) is the world-renowned Norwegian screenwriter and director of SKAM, the teen drama web series that became an unprecedented national and international success upon airing in 2015. -

Appendix: Industry Informants

APPENDIX: INDUSTRY INFORMaNTS Informants are listed alphabetically with the title and affliation they had at the time of the interview. Akrim, Rashid, Online Designer on SKAM and blank at NRK P3 Event and Development, in-person interview, Oslo, 6 March 2018 and 28 June 2018. Andressen, Anne, Editor on blank at NRK, in-person interview, Oslo, 28 May 2018 and 26 June 2018. Arnø, William Greni, Actor on blank at NRK, in-person interview, Oslo, 28 June 2018. Aspefaten, Henrik, Online Producer on blank and Assistant Online Producer on SKAM at NRK, in-person interview, Oslo, 27 September 2017 and 26 June 2018. Bettvik, Ida, Production Leader on SKAM (S4) and blank at NRK, in- person interview, Oslo, 24 November 2017 and 26 June 2018. Bjørn, Camilla, Head of NRK P3, in-person interview, Oslo, 23 March 2018. Bjørnstad, Anne, Showrunner on Lilyhammer at Rubicon TV, in-person interview, Oslo, 18 February 2015. Conesa, Cecilie Amlie, Actor on blank at NRK, in-person interview, Oslo, 28 June 2018. Eriksen, Thor Germund, Broadcasting Director at NRK, in-person inter- view, Oslo, 14 March 2018. © The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature 137 Switzerland AG 2021 V. S. Sundet, Television Drama in the Age of Streaming, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66418-3 138 APPENDIX: INDUSTRY INFORMANTS Erlandsen, Kim, Online Developer on SKAM and blank at NRK P3 Event and Development, in-person interview, Oslo, 30 November 2017 and 28 June 2018. Flesjø, Nicolay, Editorial Director of On-Demand Services at NRK, in- person interview, Oslo, 26 January 2015. -

Where We Are on Tv 2018 – 2019 Where We Are on Tv 2018 – 2019

WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2018 – 2019 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2018 – 2019 2018–2019 Where We Are on TV 1 PB WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2018 – 2019 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2018 – 2019 3 2 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2018 – 2019 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2018 – 2019 Contents 4 From the Desk of Sarah Kate Ellis 5 Methodology 6 Executive Summary 8 Summary of Broadcast Findings 10 Summary of Cable Findings 12 Summary of Streaming Findings 14 Gender Representation 16 Race & Ethnicity 18 Representation of Black Characters 20 Representation of Latinx Characters 22 Representation of Asian-Pacific Islander Characters 24 Representation of Characters With Disabilities 26 Representation of Bisexual+ Characters 28 Representation of Transgender Characters 30 Representation in Alternative Programming 31 Representation in Daytime, Kids & Family Programming 32 Representation on Other SVOD Streaming Services 33 Representation in Spanish-Language Programming 34 About GLAAD 3 2 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2018 – 2019 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2018 – 2019 From the Desk of Sarah Kate Ellis GLAAD has tracked the presence of lesbian, gay, Inclusive shows also pay off in the ratings. NBC’s bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) characters season nine premiere of Will & Grace counted 15 on television for 23 years, and this year marks our million viewers in the first week of release, ABC’s 14th report since expanding that focus into what is Modern Family ranked in the top 20 broadcast series now the Where We Are on TV (WWAOTV) report among 18-49 year old viewers for the entirety of its in 2005. -

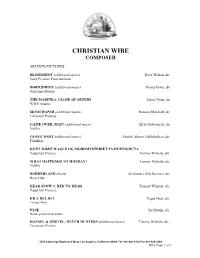

Christian Wibe Composer

CHRISTIAN WIBE COMPOSER MOTION PICTURES BLOODSHOT (additional music) Dave Wilson, dir. Sony Pictures Entertainment BORN2DRIVE (additional music) Daniel Fahre, dir. Storyline Studios THE MARINE 6: CLOSE QUARTERS James Nunn, dir. WWE Studios SKYSCRAPER (additional music) Rawson Marshall, dir. Universal Pictures GAME OVER, MAN! (additional music) Kyle Newacheck, dir. Netflix GOING WEST (additional music) Henrik Martin Dahlsbakken, dir. FilmBros KURT JOSEF WAGLE OG MORDMYSTERIET PÅ HURTIGRUTA Tappeluft Pictures Tommy Wirkola, dir. WHAT HAPPENED TO MONDAY? Tommy Wirkola, dir. Netflix BORDERLAND (short) Aleksander Olai Korsnes, dir. Rein Film DEAD SNOW 2: RED VS. DEAD Tommy Wirkola, dir. Tappeluft Pictures KILL BULJO 2 Vegar Hoel, dir. Living Films PYSE Siri Rutlin, dir. Norwegian Film Institute HANSEL & GRETEL: WITCH HUNTERS (additional music) Tommy Wirkola, dir. Paramount Pictures 3349 Cahuenga Boulevard West, Los Angeles, California 90068 Tel. 818-380-1918 Fax 818-380-2609 Wibe Page 1 of 3 CHRISTIAN WIBE COMPOSER MOTION PICTURES (Continued) FUCK UP (additional music) Øystein Karlson, dir. Via Film TOMME TØNNER Leon Bashir & Sebastian Dalén, dir. Tappeluft Pictures DEAD SNOW Tommy Wirkola, dir. Euforia Film ANIMAL ALPHA: BUNDY (short) Petter Jahre, dir. Qvisten Animation NEXT DOOR (additional music) Pål Sletaune, dir. 4 ½ Film TELEVISION DEAD OF NIGHT Shaun Higton, dir. Snapchat LIVSTID Pål Jackman, dir. Monster Scripted SKAM AUSTIN Julie Andem, dir. Facebook Watch SKAM FRANCE Julie Andem, Creator AT-Production SKAM Julie Andem, Creator Norsk Rikskringkasting (NKR) TEAM INGEBRIGTSEN Silje Evensmo Jacobsen, dir. Norsk Rikskringkasting (NKR) HELLFJORD Patrik Syversen, dir. Polyband 3349 Cahuenga Boulevard West, Los Angeles, California 90068 Tel. 818-380-1918 Fax 818-380-2609 Wibe Page 2 of 3 CHRISTIAN WIBE COMPOSER VIDEO GAMES BURNOUT LEGENDS Criterion Games VIDEO GAMES (Continued) BURNOUT REVENGE Criterion Games 3349 Cahuenga Boulevard West, Los Angeles, California 90068 Tel. -

Płacząc Po Norwesku. Serial Skam Jako Opowieść Transmedialna Dla Międzynarodowej Publiczności

328 varia Płacząc po norwesku. Serial Skam jako opowieść transmedialna dla międzynarodowej publiczności małgorzata mączko Uniwersytet Jagielloński w Krakowie Abstract. Mączko Małgorzata, Płacząc po norwesku. Serial Skam jako opowieść transmedialna dla międzyna- rodowej publiczności [Crying in Norwegian. Skam as transmedia storytelling for international audiences]. “Images” vol. XXVIII, no. 37. Poznań 2020. Adam Mickiewicz University Press. Pp. 328–337. ISSN 1731-450X. DOI 10.14746/i.2020.37.19. The article aims to analyse the phenomenon of a Norwegian Internet-TV show for teenage audiences, Skam (2015–2017). The transmedia storytelling used in this production resulted in unforeseen international acclaim, subsequently leading to the creation of local remakes of the series. The article will outline the main issues that the show has dealt with, as well as the immersion-building narrative solutions used by the creators. Moreover, it will discuss Skam’s reception by Norwegian and international audiences, and suggest potential directions for the future development of this format. Keywords: Skam, transmedia storytelling, convergence culture, immersion Można odnieść wrażenie, że o kształcie i wypełnić konkretną niszę mimo braku tak współczesnego świata seriali decyduje zaledwie imponującego produkcyjno-dystrybucyjnego garstka graczy – amerykańskie stacje telewizyj- zaplecza. W ostatnich latach fenomenem na ne, wielkie konglomeraty medialne oraz dostęp- gruncie serialu młodzieżowego stał się skromny ne niemal wszędzie platformy streamingowe. norweski tytuł, który zdobył serca nastolatków Taka diagnoza, choć powierzchowna, nie jest na całym świecie i doczekał się licznych lokal- bezpodstawna. Nietrudno bowiem dostrzec, że nych remake’ów. Wyprodukowany przez pub- w XXI wieku o żywotności i popularności seria- liczną telewizję serial Skam (2015–2017) okazał lu nie decyduje jedynie jego wartość artystycz- się niespodziewanym hitem, na którego sukces na, lecz cały splot okoliczności ekonomicznych złożyło się kilka czynników. -

Report for the APFI on the Television Market Landscape in the UK and Eire

APFI Report: UK, Eire and US Television Market Landscape • Focusing on childrens programming • See separate focus reports for drama MediaXchange encompasses consultancy, development, training and events targeted at navigating the international entertainment industry to advance the business and content interests of its clients. This report has been produced solely for the information of the APFI and its membership. In the preparation of the report MediaXchange reviewed a range of public and industry available sources and conducted interviews with industry professionals in addition to providing MediaXchange’s own experience of the industry and analysis of trends and strategies. MediaXchange may have consulted, and may currently be consulting, for a number of the companies or individuals referred to in these reports. While all the sources in the report are believed to represent current and accurate information, MediaXchange takes no responsibility for the accuracy of information derived from third-party sources. Any recommendations, data and material the report provides will be, to the best of MediaXchange’s judgement, based on the information available to MediaXchange at the time. The reports contain properly acknowledged and credited proprietary information and, as such, cannot under any circumstances be sold or otherwise circulated outside of the intended recipients. MediaXchange will not be liable for any loss or damage arising out of the collection or use of the information and research included in the report. MediaXchange Limited, 1 -

News Pioneer Digital Purchase Order

February 2019 Deborah Turness: News pioneer Digital Purchase Order Throw away your P.O. books and go digital with Digital Purchase Order Controlling cost is crucial when managing a production and our digital purchase order system allows decision makers and controllers to approve costs before payments are made. DPO simplifies the traditional purchase order workflow, providing a fully integrated process which removes the need for multiple emails and physical circulation. Digital Purchase Order benefits: Create POs in seconds Control costs Customised approval chains Multi currency; 24/7 access Digital Travel Authorisations To find out how you can save time and go paperless on your next production, visit the Digital Production Office® website www.digitalproductionoffice.com or contact us for more information: T: +44 (0)1753 630300 E: [email protected] www.sargent-disc.com www.digitalproductionoffice.com @SargentDisc @DigiProdOffice /SargentDisc /digitalproductionoffice Journal of The Royal Television Society February 2019 l Volume 56/2 From the CEO It may only be Febru- I am very grateful to Alex Wootten, Day with a special all-female episode. ary but 2019 has got Chair of RTS Futures, our exhibitors, I am thrilled that the screenwriter off to a lively start for session producers and panellists for responsible for the programme, Max- the RTS. At the Soci- making the TV Careers Fair such a ine Alderton, found time to write this ety’s London HQ we vibrant success. month’s TV Diary. have been busy host- Our latest screening was held at Elsewhere in this edition, we look at ing the juries for the Soho’s Curzon cinema last month, what are bound to be two of the year’s 2019 RTS Television Journalism and when a large crowd had the opportu- biggest issues for our sector – the RTS Programme Awards. -

Add a Headline

APFI Report: USA Television Market Landscape • Focusing on Serialised Drama • See Separate Focus Report for Childrens MediaXchange encompasses consultancy, development, training and events targeted at navigating the international entertainment industry to advance the business and content interests of its clients. This report has been produced solely for the information of the APFI and its membership. In the preparation of the report MediaXchange reviewed a range of public and industry available sources and conducted interviews with industry professionals in addition to providing MediaXchange’s own experience of the industry and analysis of trends and strategies. MediaXchange may have consulted, and may currently be consulting, for a number of the companies or individuals referred to in these reports. While all the sources in the report are believed to represent current and accurate information, MediaXchange takes no responsibility for the accuracy of information derived from third-party sources. Any recommendations, data and material the report provides will be, to the best of MediaXchange’s judgement, based on the information available to MediaXchange at the time. The reports contain properly acknowledged and credited proprietary information and, as such, cannot under any circumstances be sold or otherwise circulated outside of the intended recipients. MediaXchange will not be liable for any loss or damage arising out of the collection or use of the information and research included in the report. MediaXchange Limited, 1 Noel Street,