Heavener Runestone State Park Resource Management Plan 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NWS Tulsa Storm Data Report for May 1999

Time Path Path Number of Estimated May 1999 Local/ Length Width Persons Damage Location Date Standard (Miles) (Yards) Killed Injured Property Crops Character of Storm ARKANSAS, Northwest ARZ019-029 Crawford - Sebastian 01 0000CST 0 0 Flood 14 1900CST The Arkansas River at Van Buren started the month of May above its flood stage of 22 feet following a crest of 24.0 feet on April 28. The river remained above flood stage until 800 PM CDT on May 14. Benton County Siloam Spgs04 0200CST 0 0 Thunderstorm Wind (G52) Benton County Centerton04 0230CST 0 0 15K Thunderstorm Wind Small outbuildings were destroyed, trees were blown down, and pull-behind trailers were either damaged or moved. Washington County Prairie Grove04 0820CST 0 0 Thunderstorm Wind (G52) Carroll County Beaver04 0900CST 0 0 0.10K Thunderstorm Wind Several large tree limbs were blown down. Madison County Clifty04 0915CST 0 0 0.10K Thunderstorm Wind Several large tree limbs were blown down. Benton County Highfill04 1135CST 0 1 Lightning A man was injured when lightning struck a company trailer that he was unloading at the Northwest Arkansas Regional Airport. Crawford County 6 NW Natural Dam to04 1216CST 30175 0 3K Tornado (F3) 8 NNW Natural Dam 1220CST A significant long-track tornado first developed 4 miles west of Short, OK, moving northeast to about 7 miles southwest of Fayetteville, AR. This tornado reached its peak strength as an F3 tornado as it clipped extreme southeast Adair County, OK. This tornado then clipped extreme northwest Crawford County, passing through an unpopulated, forested area in the Ozark National Forest. -

Ragnarocks You Take on the Role of a Viking Clan Using Runestones to Mark Your Clan’S Claims of Land

1 1 IN NORSE MYTHOLOGY, HUMANS EXIST IN THE LAND OF MIDGARD - A PLACE IN THE CENTER OF THE WORLD TREE AND CONNECTED TO THE NINE REALMS. AMONG THESE NINE REALMS LIVE GODS AND GODDESSES, SERPENTS AND SPIRITS, AND ALL MANNER OF MYTHICAL AND MYSTICAL CREATURES. In Ragnarocks you take on the role of a Viking clan using Runestones to mark your clan’s claims of land. In the advanced game, your clan worships one of these powerful beings from another realm who lends you their power to help you outwit rivals and claim territories for your clan. At the end of the game, the clan who controls the most territory in Midgard wins! Contents Heimdallr Odin Guardian of Asgard Sól Ruler of the Aesir Goddess of the Sun Art Coming Soon Art Coming Soon Art Coming Soon SETUP: Draw two additional Mythology Powers with [Odin icon] andCommand hold them. cards. These are your START OF YOUR TURN: AT THE END OF YOUR TURN: You may relocate one of your vikings Settled You may either play a Command card this turn to any unoccupied space that was from your hand, or pick up all your played BEFORE YOUR MOVE: not Settled at the beginning of this turn. You may Move one space with Command cards. If you play a Command your Selected Viking card, you gain(ignore that setuppower powers). until your next turn 32 Mythology Cards 40 Runestones 6 Viking Pawns 1 Tree Stand 1 Game Insert Board 2 3 basic game setup 1 Remove game pieces from the insert and set them where all players can reach them. -

Herjans Dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age

Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age Luke John Murphy Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Félagsvísindasvið Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age Luke John Murphy Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Leiðbeinandi: Terry Gunnell Félags- og mannvísindadeild Félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands 2013 Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni Trú og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Luke John Murphy, 2013 Reykjavík, Ísland 2013 Luke John Murphy MA in Old Nordic Religions: Thesis Kennitala: 090187-2019 Spring 2013 ABSTRACT Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Feminities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age This thesis is a study of the valkyrjur (‘valkyries’) during the late Iron Age, specifically of the various uses to which the myths of these beings were put by the hall-based warrior elite of the society which created and propagated these religious phenomena. It seeks to establish the relationship of the various valkyrja reflexes of the culture under study with other supernatural females (particularly the dísir) through the close and careful examination of primary source material, thereby proposing a new model of base supernatural femininity for the late Iron Age. The study then goes on to examine how the valkyrjur themselves deviate from this ground state, interrogating various aspects and features associated with them in skaldic, Eddic, prose and iconographic source material as seen through the lens of the hall-based warrior elite, before presenting a new understanding of valkyrja phenomena in this social context: that valkyrjur were used as instruments to propagate the pre-existing social structures of the culture that created and maintained them throughout the late Iron Age. -

Oklahoma SCORP This Page Intentionally Left Blank

Oklahoma’s State of Health: The People, the Economy, and the Environment 2018 – 2022 2017 Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan The 2017 Oklahoma SCORP This page intentionally left blank. OKLAHOMA TOURISM AND RECREATION COMMISSION Todd Lamb Lt. Governor—Chair Ronda Roush Commissioner Dr. Rick Henry Commissioner Grant Humphreys Commissioner Chuck Perry Commissioner Mike Wilt Commissioner James Farris Commissioner OKLAHOMA TOURISM AND RECREATION DEPARTMENT Dick Dutton Executive Director Kris Marek Director of State Parks Doug Hawthorne Assistant Director State Parks Susan Henry Grant Program Administrator This page intentionally left blank. Oklahoma’s State of Health: The People, the Economy, and the Environment 2018 – 2022 Fatemeh (Tannaz) Soltani, Ph.D. Lowell Caneday, Ph.D. December 2017 Acknowledgements As a part of the legacy of the 1960s, the United States Congress implemented the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission and, for the first time in the history of humans, a nation documented its natural resources with a focus on outdoor recreation. That review led to authorization of the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) – a grant program to aid states and sub-state units in acquiring and developing outdoor recreation resources to meet needs of a changing society. Over the balance of the 20th century and continuing into the 21st century, society and technology related to outdoor recreation changed dramatically. Oklahoma has benefited greatly from grants through LWCF, as have cities, towns, and schools across the state. Tennis courts, parks, trails, campgrounds, and picnic areas remain as the legacy of LWCF and statewide planning. Oklahoma has sustained a commitment since 1967 to complete the federally mandated Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) every five years. -

Ridgeway Baptist Church Delight United (SBC) Corner of Peachtree & Hearn Methodist Church ��Y

THE NASHVILLE H News-LEADER H H Preserving Southwest Arkansas’s Heritage While Leading Through the 21st Century H Wednesday, Sept. 28, 2016 u Vol. 14, Issue 13 u 24 pages, 2 sections u 75¢ Leader New physician opens ofice; Board family practice to be focus www.swarkansasnews.com By Terrica Hendrix owned a bakery and a French intellectually and would be a News-Leader staff restaurant, was from Michigan.” career where I could ofer as- OPINION 4A Howard Memorial Hospital’s Wilkins’ maternal grand- sistance to others. Growing up newest physician, Dr. Ngozi A. parents are originally from in Nigeria, health disparities Disappointment Wilkins, is “Every Woman.” Arkansas. She was reared with were often apparent. Out of She is a wife, mother and a two younger sisters and one pocket costs for health care were for Razorback physician. brother. “I grew up knowing cost prohibitive for some, and fan after loss Dr. Wilkins recently opened that education was not an op- to receive care, payment was to Aggies. her family medicine clinic on tion; it was a necessity. My par- needed. Those who could not HMH’s medical campus. ents always exposed us to the aford medical services were not She was raised in Nigeria, languages, arts and music; and able to get treated and would West Africa, on the campus of we often visited various univer- have to raise funds to pay for Band seeks “I igured medicine would the University of Ibadan, “one of sities across the United States.” care. I also experienced the loss instruments be a good ield as it would the oldest and most prestigious Wilkins said that her love of a cousin to typhoid fever keep me challenged intellec- Nigerian universities, where my for the sciences - especially bi- and another to malaria [both regardless tually and would be a career father was a Professor of Psy- ology - at an early age is what preventable diseases] and my chology,” she said. -

Final Impact Statement for the Proposed Habitat Conservation Plan for the Endangered American Burying Beetle

Final Environmental Impact Statement For the Proposed Habitat Conservation Plan for the Endangered American Burying Beetle for American Electric Power in Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Texas Volume II: Appendices September 2018 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southwest Region Albuquerque, NM Costs to Develop and Produce this EIS: Lead Agency $29,254 Applicant (Contractor) $341,531 Total Costs $370,785 Appendix A Acronyms and Glossary Appendix A Acronyms and Glossary ACRONYMS °F Fahrenheit ABB American burying beetle AEP American Electric Power Company AMM avoidance and minimization measures APE Area of Potential Effects APLIC Avian Power Line Interaction Committee APP Avian Protection Plan Applicant American Electric Power Company ATV all-terrain vehicles BGEPA Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act BMP best management practices CE Common Era CFR Code of Federal Regulations Corps Army Corps of Engineers CPA Conservation Priority Areas CWA Clean Water Act DNL day-night average sound level EIS Environmental Impact Statement EMF electric magnetic fields EPA Environmental Protection Agency ESA Endangered Species Act FEMA Federal Emergency Management Agency FR Federal Register GHG greenhouse gases HCP American Electric Power Habitat Conservation Plan for American Burying Beetle in Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Texas ITP Incidental Take Permit MDL multi-district litigation NEPA National Environmental Policy Act NHD National Hydrography Dataset NOI Notice of Intent NPDES National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System NRCS Natural Resources Conservation Service NWI National Wetlands Inventory NWR National Wildlife Refuge OSHA Occupational Safety and Health Administration ROD Record of Decision ROW right-of-way American Electric Power Habitat Conservation Plan September 2018 A-1 Environmental Impact Statement U.S. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

Cunningham Tarpaulin Sky in Utero

! TWO: THE ICE LAND ICE ARENA cold eyes blue eyes cold eyes dead eyes red eyes dead eyes what breaks the eyes skates up and down the eyes up, the eyes down the eyes, cold eyes bite cold eyes blue eyes cold eyes on thin eyes, you’re on thin eyes skating, wound on eyes, skating red eyes A-20 Aircraft— Wagner’s Valkyries knows, dives a soldier’s nerves Chassis— grief stains, skeleton of screaming metal priceless lie-down Engine— auto-translation power supply with mess, with Wooden Box— ice jamming coffin-lidded gorged on 8s Runestone— hell-raised audience guide all, different voices A-20 Aircraft— hell-raised coffin-lidded priceless lie-down Chassis— audience guide a soldier’s nerves ice jamming Engine— grief stains, skeleton with mess, with auto-translation Wooden Box— of screaming metal knows, dives all, different voices Runestone— gorged on 8s Wagner’s Valkyries power supply A-20 Aircraft— grief stains, skeleton gorged on 8s audience guide Chassis— a soldier’s nerves of screaming metal with mess, with Engine— Wagner’s Valkyries knows, dives power supply Wooden Box— all, different voices ice jamming coffin-lidded Runestone— auto-translation priceless lie-down hell-raised A-20 Aircraft— coffin-lidded priceless lie-down hell-raised Chassis— of screaming metal with mess, with grief stains, skeleton Engine— power supply knows, dives ice jamming Wooden Box— gorged on 8s a soldier’s nerves all, different voices Runestone— Wagner’s Valkyries auto-translation audience guide A-20 Aircraft— of screaming metal audience guide with mess, with Chassis— -

Eagle Rock Loop Trail Recreational Trail the Ground

It’s a simple thing, really: a well-trod path through a place otherwise untouched, a scraggly aisle cut through a sun-dappled canopy. It’s rudimental and practical. It’s a way through. But as the eight routes featured in these pages prove, an Arkansas hiking trail can be far, far more than just a means to an end Edited by Wyndham Wyeth 60 ARKANSAS LIFE www.arkansaslife.com OCTOBER 2016 ARKANSAS LIFE 61 R. Kenny Vernon 64 Nature Trail 76 Ouachita National “Stand absolutely still and study Eagle Rock Loop Trail Recreational Trail the ground. Look for the clusters of acorns the blackjack oak has tossed aside; the horn of plenty ’VE ALWAYS BEEN OF THE MIND THAT those may live nearby.” who talk down about Arkansas have never actually set foot in the state. Surely, those folks have never been fortunate enough to see the unyielding natural beauty that abounds in this neck of the woods we call home. When it comes to the great outdoors, the variety found in The Natural State is inexhaustible. From the IBuffalo, the country’s first national river, to our state’s highest peak on Mount Magazine, and all manner of flora and fauna in between, the call of the Arkansas wild is difficult to resist. 70 But if you want to discuss Arkansas and its eminence in all things outside, you’d be remiss if you failed to address the hiking trails, Mount Nebo Bench Trail those hand-cut paths through terrain both savage and tamed that represent Arkansas in its purest form. -

2018-2019 Program Resource Book Table of Contents

You Can Be Anything! As many of you know, each year I have a President and CEO patch designed to give to the girls I meet. My patches are based on stories from my sons. Each son, who are now grown men, decided what they felt was one of the most important life lessons I have taught them. They said if the lesson was good enough for them, they would also be good for the girls. My first patch, from my oldest son, Benjamin, who now has a daughter of his own, is “Make Wise Choices.” Spencer, my second son, remembers me always telling him “It is important to look in the mirror and like who he sees looking back,” so this message became my second patch. My third son, Brooks, suffered with a physical disability as a young boy. He learned it was best to “Be Kind” even if others were not kind to him. He was very clear that his patch would be the “Be Kind” patch. That brings me to my newest patch. Christian, my stepson, was excited to get his own patch. When I first met him, he was very shy. He was always encouraged to try and experience everything life had to offer to help him get over his shyness and find his passion. Due to this encouragement he is now pursuing his dream of being a rock star – because he can be anything! This program book provides countless opportunities for girls to make choices, like the girl they are becoming, be kind in their service to others and realize they can be anything. -

University of Oklahoma

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE WISTER AREA FOURCHE MALINE: A CONTESTED LANDSCAPE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By SIMONE BACHMAI ROWE Norman, OKlahoma 2014 WISTER AREA FOURCHE MALINE: A CONTESTED LANDSCAPE A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY BY ______________________________ Dr. Lesley RanKin-Hill, Co-Chair ______________________________ Dr. Don Wyckoff, Co-Chair ______________________________ Dr. Diane Warren ______________________________ Dr. Patrick Livingood ______________________________ Dr. Barbara SafiejKo-Mroczka © Copyright by SIMONE BACHMAI ROWE 2014 All Rights Reserved. This work is dedicated to those who came before, including my mother Nguyen Thi Lac, and my Granny (Mildred Rowe Cotter) and Bob (Robert Cotter). Acknowledgements I have loved being a graduate student. It’s not an exaggeration to say that these have been the happiest years of my life, and I am incredibly grateful to everyone who has been with me on this journey. Most importantly, I would like to thank the Caddo Nation and the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes for allowing me to work with the burials from the Akers site. A great big thank you to my committee members, Drs. Lesley Rankin-Hill, Don Wyckoff, Barbara Safjieko-Mrozcka, Patrick Livingood, and Diane Warren, who have all been incredibly supportive, helpful, and kind. Thank you also to the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, where most of this work was carried out. I am grateful to many of the professionals there, including Curator of Archaeology Dr. Marc Levine and Collections Manager Susie Armstrong-Fishman, as well as Curator Emeritus Don Wyckoff, and former Collection Managers Liz Leith and Dr. -

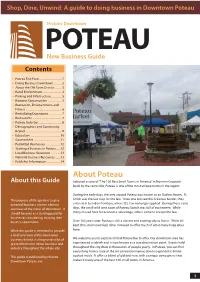

A Guide to Doing Business in Downtown Poteau

Shop, Dine, Unwind: A guide to doing business in Downtown Poteau Historic Downtown POTEAU New Business Guide Contents • Poteau Fast Facts ................................2 • Doing Business Downtown ............2 • About the Old Town District ...........3 • Retail Environment ............................3 • Parking and Infastructure ................5 • Business Opportunites ....................5 • Recreation, Entertainment, and Fitness ....................................................6 • Revitalizing Downtown ...................7 • Restaurants ..........................................7 • Poteau Industry ..................................8 • Demographics and Community Report ....................................................9 • Education ...........................................10 • Government ......................................11 • Permitted Businesses .....................12 • Starting a Business in Poteau ......12 • Local Business Resources .............13 • National Business Resources .......13 • Publisher Information ....................14 About Poteau About this Guide Selected as one of “The 100 Best Small Towns in America” in Norman Crapton’s book by the same title, Poteau is one of the most unique towns in the region. During the early days, the area around Poteau was known as an Outlaw Haven. Ft. The purpose of this guide is to give Smith was the last stop for the law. Once one crossed the Arkansas border, they potential business owners a broad entered in to Indian Territory, where U.S. law no longer applied. During those early overview of the status of downtown. It days, the small wild west town of Poteau Switch was full of excitement. While should be used as a starting point for many moved here for economic advantage, others came to escape the law. businesses considering locating their business downtown. Over 100 years later, Poteau is still a vibrant and exciting city to live in. While it’s kept that small town feel, it has matured to offer much of what many large cities While this guide is intended to provide have.