Winnipeg Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Municipal Officials Directory 2021

MANITOBA MUNICIPAL RELATIONS Municipal Officials Directory 21 Last updated: September 23, 2021 Email updates: [email protected] MINISTER OF MUNICIPAL RELATIONS Room 317 Legislative Building Winnipeg, Manitoba CANADA R3C 0V8 ,DPSOHDVHGWRSUHVHQWWKHXSGDWHGRQOLQHGRZQORDGDEOH0XQLFLSDO2IILFLDOV'LUHFWRU\7KLV IRUPDWSURYLGHVDOOXVHUVZLWKFRQWLQXDOO\XSGDWHGDFFXUDWHDQGUHOLDEOHLQIRUPDWLRQ$FRS\ FDQEHGRZQORDGHGIURPWKH3URYLQFH¶VZHEVLWHDWWKHIROORZLQJDGGUHVV KWWSZZZJRYPEFDLDFRQWDFWXVSXEVPRGSGI 7KH0XQLFLSDO2IILFLDOV'LUHFWRU\FRQWDLQVFRPSUHKHQVLYHFRQWDFWLQIRUPDWLRQIRUDOORI 0DQLWRED¶VPXQLFLSDOLWLHV,WSURYLGHVQDPHVRIDOOFRXQFLOPHPEHUVDQGFKLHI DGPLQLVWUDWLYHRIILFHUVWKHVFKHGXOHRIUHJXODUFRXQFLOPHHWLQJVDQGSRSXODWLRQV,WDOVR SURYLGHVWKHQDPHVDQGFRQWDFWLQIRUPDWLRQRIPXQLFLSDORUJDQL]DWLRQV0DQLWRED([HFXWLYH &RXQFLO0HPEHUVDQG0HPEHUVRIWKH/HJLVODWLYH$VVHPEO\RIILFLDOVRI0DQLWRED0XQLFLSDO 5HODWLRQVDQGRWKHUNH\SURYLQFLDOGHSDUWPHQWV ,HQFRXUDJH\RXWRFRQWDFWSURYLQFLDORIILFLDOVLI\RXKDYHDQ\TXHVWLRQVRUUHTXLUH LQIRUPDWLRQDERXWSURYLQFLDOSURJUDPVDQGVHUYLFHV ,ORRNIRUZDUGWRZRUNLQJLQSDUWQHUVKLSZLWKDOOPXQLFLSDOFRXQFLOVDQGPXQLFLSDO RUJDQL]DWLRQVDVZHZRUNWRJHWKHUWREXLOGVWURQJYLEUDQWDQGSURVSHURXVFRPPXQLWLHV DFURVV0DQLWRED +RQRXUDEOHDerek Johnson 0LQLVWHU TABLE OF CONTENTS MANITOBA EXECUTIVE COUNCIL IN ORDER OF PRECEDENCE ............................. 2 PROVINCE OF MANITOBA – DEPUTY MINISTERS ..................................................... 5 MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY ............................................................ 7 MUNICIPAL RELATIONS .............................................................................................. -

Divided Prairie City Summary

summary the divided prairie city Income Inequality Among Winnipeg’s Neighbourhoods, 1970–2010 Edited by Jino Distasio and Andrew Kaufman Tom Carter, Robert Galston, Sarah Leeson-Klym, Christopher Leo, Brian Lorch, Mike Maunder, Evelyn Peters, Brendan Reimer, Martin Sandhurst, and Gina Sylvestre. This handout summarizes findings from The Divided Prairie City released by the Institute of Urban Studies Incomes are growing less (IUS) at The University of Winnipeg. 4 equal in Winnipeg. The IUS is part of a Neighbourhood Change Research Partner- ship (NCRP) funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities From 1970 to 2010, income inequality in Winnipeg grew by 20%. Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). Led by the Cities Cen- • 40% of Winnipeg’s neighbourhoods experienced declining tre at the University of Toronto, this study examines income incomes from 1980 to 2010—only 16% of Winnipeg’s neigh- inequality in Halifax, Montreal, Toronto, Hamilton, Winnipeg, bourhoods experienced increasing incomes. Calgary, and Vancouver. • Income inequality has not grown in Winnipeg to the same extent that it has in Toronto, Calgary, or Vancouver. Instead, Winnipeg resembles cities like Edmonton and Halifax because Income inequality is of lower concentrations of ultra high-income individuals. growing in Canada. Middle-income neighbour- 1 hoods are disappearing. Canadians believe that we live in a middle-class country, yet research 5 points to a growing income gap bet ween rich and poor neighbour- • From 1980 to 2010, one quarter of Winnipeg’s middle and up- hoods while the middle-income group shrinks. per middle-income neighbourhoods saw incomes decline to below average amounts. Incomes grew in only 13% of mid- Fourteen per cent of all income in Canada is now received by dle-income areas to above-average levels. -

5G Cell “Towers” in Winnipeg Neighbourhoods No Radiation Without Consultation

5G Winnipeg Awareness 3rd 5G CALL TO ACTION, 6 June 2020 TO: Mayor Bowman and City Councillors Province of Manitoba Manitoba Hydro Government of Canada ------------- No 4G/ 5G Cell “towers” in Winnipeg Neighbourhoods No Radiation without Consultation June 6, 2020 To all Winnipeggers and friends of Winnipeggers concerned about wireless 5G rollout, especially the installations of all sizes of cellular network antennas close to our homes CITY OF WINNIPEG The process for the City of Winnipeg to begin permitting of small cell antennas is underway. At least 3,400 small 4G/5G antennas and perhaps more than 7,000, many in our neighbourhoods. On lamp posts, hydro poles, traffic lights, sides and atop buildings. At least one on every block. Emitting 4G LTE 24/7 and then adding 5G when the technology is ready. POSSIBLE ACTIONS: 1. For the next Innovation, Economic and Development (IED) Standing Committee meeting -perhaps Monday, June 15th: • Delegate (=present) via phone, Skype or Zoom and/or submit a written report. Contact the City Clerk at https://www.winnipeg.ca/shared/htmlsnippets/MailForm.asp?Recipient=CityClerks&Title=DMIS%20Contact%2 0Form&Subjects=Feedback Watch to see when the next IED meeting will be and whether “small cells” are on the agenda: http://clkapps.winnipeg.ca/dmis/DocSearch.asp?CommitteeType=ASD&DocumentType=A • Send emails to Mayor Bowman and each City of Winnipeg Councillor (not just yours) - the more, the better (contact information below) 1/4 A SUGGESTED MESSAGE: Mention that you are a stakeholder, too. Just as the telecommunications providers have a voice, so should we. -

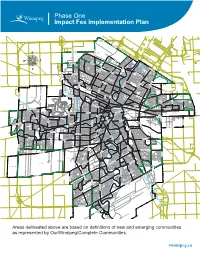

Impact Fee Implementation Plan

Phase One Impact Fee Implementation Plan ROSSER-OLD KILDONAN AMBER TRAILS RIVERBEND LEILA NORTH WEST KILDONAN INDUSTRIAL MANDALAY WEST RIVERGROVE A L L A TEMPLETON-SINCLAIR H L A NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL INKSTER GARDENS THE MAPLES V LEILA-McPHILLIPS TRIANGLE RIVER EAST MARGARET PARK KILDONAN PARK GARDEN CITY SPRINGFIELD NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL PARK TYNDALL PARK JEFFERSON ROSSMERE-A KILDONAN DRIVE KIL-CONA PARK MYNARSKI SEVEN OAKS ROBERTSON McLEOD INDUSTRIAL OAK POINT HIGHWAY BURROWS-KEEWATIN SPRINGFIELD SOUTH NORTH TRANSCONA YARDS SHAUGHNESSY PARK INKSTER-FARADAY ROSSMERE-B BURROWS CENTRAL ST. JOHN'S LUXTON OMAND'S CREEK INDUSTRIAL WESTON SHOPS MUNROE WEST VALLEY GARDENS GRASSIE BROOKLANDS ST. JOHN'S PARK EAGLEMERE WILLIAM WHYTE DUFFERIN WESTON GLENELM GRIFFIN TRANSCONA NORTH SASKATCHEWAN NORTH DUFFERIN INDUSTRIAL CHALMERS MUNROE EAST MEADOWS PACIFIC INDUSTRIAL LORD SELKIRK PARK G N LOGAN-C.P.R. I S S NORTH POINT DOUGLAS TALBOT-GREY O R C PEGUIS N A WEST ALEXANDER N RADISSON O KILDARE-REDONDA D EAST ELMWOOD L CENTENNIAL I ST. JAMES INDUSTRIAL SOUTH POINT DOUGLAS K AIRPORT CHINA TOWN C IVIC CANTERBURY PARK SARGENT PARK CE TYNE-TEES KERN PARK NT VICTORIA WEST RE DANIEL McINTYRE EXCHANGE DISTRICT NORTH ST. BONIFACE REGENT MELROSE CENTRAL PARK SPENCE PORTAGE & MAIN MURRAY INDUSTRIAL PARK E TISSOT LLIC E-E TAG MISSION GARDENS POR TRANSCONA YARDS HERITAGE PARK COLONY SOUTH PORTAGE MISSION INDUSTRIAL THE FORKS DUGALD CRESTVIEW ST. MATTHEWS MINTO CENTRAL ST. BONIFACE BUCHANAN JAMESWOOD POLO PARK BROADWAY-ASSINIBOINE KENSINGTON LEGISLATURE DUFRESNE HOLDEN WEST BROADWAY KING EDWARD STURGEON CREEK BOOTH ASSINIBOIA DOWNS DEER LODGE WOLSELEY RIVER-OSBORNE TRANSCONA SOUTH ROSLYN SILVER HEIGHTS WEST WOLSELEY A NORWOOD EAST STOCK YARDS ST. -

Property Taxes and Built Form: Mapping the City of Winnipeg By: Felipe A

Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg$ X.xx - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - -

ORGANIZATIONS FUNDED in 2018 (Winnipeg

ORGANIZATIONS FUNDED IN 2018 (Winnipeg - sorted by area) ORGANISATIONS FINANCÉES EN 2018 (Winnipeg - classées par secteur) Charleswood-Tuxedo Archers & Bowhunters Assoc of MB Assiniboine Park Conservancy Canadian Mennonite University Family Dynamics of Winnipeg Fort Whyte Alive Friends of the Harte Trail Grace Community Church Manitoba Cycling Association Manitoba Sailing Assoc. Nature Manitoba Oasis Community Church Purple Loosestrife Project of Manitoba Rotary Club of Winnipeg - Charleswood Varsity View Community Centre Winnipeg Military Family Resource Centre Winnipeg South Minor Baseball Association Daniel McIntyre Daniel McIntyre / St. Matthew's Comm. Assoc. Emmanuel Mission Church Ethio-Canadian Cultural Academy Girls with Pride and Dignity Foundation Living Bible Explorers (Winnipeg) Mission Baptist Church Monyjang Society of Manitoba Mood Disorders Association of Manitoba Robert A. Steen Memorial Community Centre Sargent Park Lawn Bowling Club Spence Neighbourhood Assoc. Valour Community Centre West Central Community Program West Central Women's Resource Centre West End BIZ Wii Chii Waakanak Learning Centre Winnipeg Art Gallery Winnipeg School Division (special needs project) Elmwood-East Kildonan Bronx Park Community Centre Chalmers Community Centre Chalmers Neighbourhood Renewal Corp. Congo Canada Charity Foundation East Elmwood Community Centre Elmwood Community Resource Centre Elmwood Giants Baseball Club Elmwood Mennonite Brethren Church Frontier College Hope Centre Ministries One Hope Min. of Canada-Adventure Day Camp River -

WOMEN of RED RIVER

III ‘Signett) SeUcirJc Mu.chc Wkeseab ifidikcuiewikumaie Kayajieahebiiwa Marie Hit ^ ISark LeSonnemt La. Robt Narrt L’homnveNoir Pego Onckidoat His JScLrk Hit Mark. Premier m M Signal irv Presence of Thorncus TTwrnae James Bird> F. MatOiey Cap: F d/Orsonnens Cap P SKETCH-MAP attached to the Miles MicdUmHl trea:^ made by Lord Selkirk wi¬ I. BP ChF oLe JCorvrrvLcr th the Indians on July l&f^l81T, Lotas NollrvJ^ at the. Forks ^the F^d and the Assiniboine. ^ *=. <=. ^ By f/iat t/vdfj; the Indiawi gMe up tJieir title to the Lxnd. “exteruilng to the ciuitdnce o^-=i t\Vo Euglish. statute inUes Jhom the banks the said rivers on. each sidel and to "six niiies on. every side'yi'oni Fort Douglas‘==i (below the Forks) and Fort Daer (at tiie ino~ u-th qF the PenibhwL. river), in considei^aii' on qpa quit-rent of' two huncb'ecL poiuids' weight of' "good, nwix^hanfahle tobaecd', to Be paid on or b^hre October lO**^ql'easdi year, one half' to be delivered at the Forks to the chi^'and warriors' of' tJie Chippe' way, or Sauiteaux, iLatton, out id theoth- er at Portage la Prairie to the. chh^'s *=. and warriors lythe HjiistuieauxorCree, nation. The Indians' version of' the t/eaty was that they gave the Silver Chhg', as thy Tiarned Lotd SeUiuk.. the land back. from‘=^ the river barJ\S as jln' as daylight could be seen under the body of a pony siandirg on the level prairie. ‘=' '=' ‘-=' '==' WOMEN OP RED RIVER “Out and in the river is winding The links of its long, red chain.” vST. -

Oct. 22, 2014 280062632.Html

October 22, 2014 Winnipeg Free Press Winnipeg votes: Oct. 22, 2014 http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/special/civicelection2014/Winnipeg-votes-Oct-22-2014- 280062632.html Voter turnout highest in a decade http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/special/civicelection2014/Voter-turnout-reaches-record-high- 280117922.html Schreyer unseats Steen in Elmwood-East Kildonan http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/special/civicelection2014/Schreyer-unseats-Steen-in-Elmwood- East-Kildonan-280133982.html Voters stick with status quo for school boards http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/special/civicelection2014/Voters-stick-with-status-quo-for-school- boards-280139482.html Gilroy seizes Daniel McIntyre after close race http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/special/civicelection2014/Gilroy-seizes-Daniel-McIntyre-after- close-race-280140232.html Morantz edges Duncan in Charleswood-Tuxedo http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/special/civicelection2014/Morantz--280137682.html Lukes wins boss’ vacated seat in St. Norbert http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/special/civicelection2014/stnorbert/Lukes-wins-boss-former-seat- in-St-Norbert-280141542.html?cx_navSource=d-more-news Devi Sharma squeaks in win in Old Kildonan http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/special/civicelection2014/oldkildonan/Devi-Sharma-squeaks-in- Old-Kildonan-win-over-Hrynyk-280138762.html?cx_navSource=d-more-news Pagtakhan retains Point Douglas seat http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/special/civicelection2014/pointdouglas/Pagtakhan-- 280138702.html?cx_navSource=d-more-news Dobson finds his groove in fourth election attempt http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/special/civicelection2014/stcharles/Dobson-- 280137812.html?cx_navSource=d-more-news Wyatt reinstated in Transcona http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/special/civicelection2014/transcona/Wyatt-reinstated-in- Transcona-280136792.html?cx_navSource=d-more-news Orlikow beats Taz in River Heights-Fort Garry http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/special/civicelection2014/riverheights/Orlikow-secures-third-term- in-River-Heights-Fort-Garry-280135492.html?cx_navSource=d-more-news Mayes re-elected in St. -

An Economic and Social Analysis of Childcare in Winnipeg Table of Contents

TIME FOR ACTION An Economic and Social Analysis of Childcare in Winnipeg Table of Contents Executive Summary . 2 Sommaire . 4 The City-Childcare Connection . 6 Development and Childcare . 9 Childcare and the Winnipeg Economy . 12 Winnipeg’s Childcare Services . 14 Childcare: Who is Responsible? . 18 What Winnipeggers Say About Childcare . 21 What Other Canadian Cities do for Childcare . 23 Time for Action: Recommendation . 26 Maps . 27 Methodological Notes . 30 Appendix and Acknowledgments . 33 Works Cited . 34 Time For Action 1 Executive Summary his report has been prepared by the Child Care Coalition of Manitoba, and is intended to stimulate a ‘made-in-Winnipeg’ discussion of childcare, and T spark some homegrown solutions. The project was led by a broad Advisory Council of leading Winnipeggers and involved over a dozen community consultations in ten neighbourhoods, in addition to original and secondary data analysis. It provides detailed quantitative and qualitative evidence of the economic and social impact of childcare in our Winnipeg community, as well as information on what other Canadian cities are doing on the issue. The childcare sector has a significant economic and social impact in Winnipeg. It enables parents to work, and reduces poverty. Childcare, just like a transportation system, is a part of the urban infrastructure that enables people to get to work. Employers need childcare, since their bottom line is hurt when they can’t recruit and retain staff. Children benefit in demonstrable ways from early childhood care. Good quality childcare, research shows, is good for children, good for mothers, good for their families, and good for society. -

To 4G and 5G Cell “Towers” in Winnipeg Neighbourhoods Contact Your Elected Representatives and Ask Them What Position They Have on This Issue

STOP 5G - CALL TO ACTION Contact information – Say “NO” to 4G and 5G cell “towers” in Winnipeg neighbourhoods Contact your elected representatives and ask them what position they have on this issue. A. CITY OF WINNIPEG COUNCIL – CONTACT INFORMATION Council Member Ward Phone Email Mayor Brian Bowman Mayor 204-986-5665 [email protected] Brian Mayes St. Vital 204-986-5088 [email protected] Cindy Gilroy Daniel McIntyre 204-986-5951 [email protected] Devi Sharma Old Kildonan 204-986-5264 [email protected] Janice Lukes Waverley West 204-986-6824 [email protected] Jason Schreyer Elmwood 204-986-5195 [email protected] Jeff Browaty North Kildonan 204-986-5196 [email protected] John Orlikow River Heights - Fort Garry 204-986-5236 [email protected] Kevin Klein Charleswood - Tuxedo 204-986-5232 [email protected] Matt Allard St. Boniface 204-396-4636 [email protected] Markus Chambers St. Norbert - Seine River 204-986-5920 [email protected] Ross Eadie Mynarski 204-986-5188 [email protected] Scott Gillingham St. James 204-986-5848 [email protected] Shawn Nason Transcona 204-986-8087 [email protected] Sherri Rollins Fort Rouge - East Fort Garry 204-986-5878 [email protected] Vivian Santos Point Douglas 204-986-8401 [email protected] • City of Winnipeg councillors can pass motions as in Niagara Falls, Ontario and several municipalities in Quebec. • Sign up for ENGAGE WINNIPEG: The city has said it will keep people informed and accept feed-back B. Provincial- Member of the Legislative Assembly Find your MLA_ https://www.gov.mb.ca/legislature/members/mla_list_alphabetical.html C. -

Patterns of Population Growth and Ethnic Relationships in Winnipeg, 1874-1974 by Alan F .J

Patterns of Population Growth and Ethnic Relationships in Winnipeg, 1874-1974 by Alan F .J. ARTIBISE * An account of Winnipeg's evolution into a modern cosmopolitan metropolis does not easily divide itself into periods of victory and defeat, progress and decline. The patterns of population growth and the ethnic relationships of the people during the years 1874-1974 are not easily described or analysed. The rate of population growth and the nature of ethnic relationships in the city were, on the one hand, the result of conscious decisions made by the residents. Population growth, for exam ple, was often encouraged - if not initiated - by various groups in the city. On the other hand, Winnipeg was also the passive recipient of immigrants through larger regional, national, or international forces. The ethnic relationships of Winnipeg residents at any given time were in part a reflection of the age of the community, the state of technology, and general economic conditions. Furthermore, the conflict, confusion, and tension that were inescapable facts of life in the city were often juxtaposed with examples of co-operation, order, and harmony. But although it is impossible in this short space to deal with all the events, deci sions, and trends that shaped the character of Winnipeg by 1974, it is possible to outline the major patterns that the city experienced. At the outset, however, two general observations are necessary. First, Winnipeg's population growth rate was not constant throughout the past century. Rather, the city grew spasmodically, with bursts of activity interspersed with periods when the city grew very slowly, if at all. -

Urban Change in Winnipeg: the Adoption of Bill 36

Urban Change in Winnipeg: The Adoption of Bill 36 __________________ by Tom Axworthy 1972 __________________ The Institute of Urban Studies FOR INFORMATION: The Institute of Urban Studies The University of Winnipeg 599 Portage Avenue, Winnipeg phone: 204.982.1140 fax: 204.943.4695 general email: [email protected] Mailing Address: The Institute of Urban Studies The University of Winnipeg 515 Portage Avenue Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3B 2E9 URBAN CHANGE IN WINNIPEG: THE ADOPTION OF BILL 36 Published 1972 by the Institute of Urban Studies, University of Winnipeg © THE INSTITUTE OF URBAN STUDIES Note: The cover page and this information page are new replacements, 2016. The Institute of Urban Studies is an independent research arm of the University of Winnipeg. Since 1969, the IUS has been both an academic and an applied research centre, committed to examining urban development issues in a broad, non-partisan manner. The Institute examines inner city, environmental, Aboriginal and community development issues. In addition to its ongoing involvement in research, IUS brings in visiting scholars, hosts workshops, seminars and conferences, and acts in partnership with other organizations in the community to effect positive change. a) I /1) IJ I ;-J !::- & {) /2BA N6; 120 ())T if " INSTITUTE OF URB.~N STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF \N\NNI~EG . 515 PORTAGE AVENU~. WINNIPEG. MANITOBA R3B 2E9 URBAN CHANGE IN vJINNIPEG; THE ADOPTION OF BILL 36 by Tom Axworthy July, 1972 1. Introduction One of the most pressing questions currently being asked in Canada is whether our nineteenth century local government structures impede the solution of twentieth century urban problems? The answer of late most often has been, yes.