Its Work to Achieve a New Regeneration Railway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of the East London Line

HISTORY OF THE EAST LONDON LINE – FROM BRUNEL’S THAMES TUNNEL TO THE LONDON OVERGROUND by Oliver Green A report of the LURS meeting at All Souls Club House on 11 October 2011 Oliver worked at the London Transport Museum for many years and was one of the team who set up the Covent Garden museum in 1980. He left in 1989 to continue his museum career in Colchester, Poole and Buckinghamshire before returning to LTM in 2001 to work on its recent major refurbishment and redisplay in the role of Head Curator. He retired from this post in 2009 but has been granted an honorary Research Fellowship and continues to assist the museum in various projects. He is currently working with LTM colleagues on a new history of the Underground which will be published by Penguin in October 2012 as part of LU’s 150th anniversary celebrations for the opening of the Met [Bishops Road to Farringdon Street 10 January 1863.] The early 1800s saw various schemes to tunnel under the River Thames, including one begun in 1807 by Richard Trevithick which was abandoned two years later when the workings were flooded. This was started at Rotherhithe, close to the site later chosen by Marc Isambard Brunel for his Thames Tunnel. In 1818, inspired by the boring technique of shipworms he had studied while working at Chatham Dockyard, Brunel patented a revolutionary method of digging through soft ground using a rectangular shield. His giant iron shield was divided into 12 independently moveable protective frames, each large enough for a miner to work in. -

Southern Railway Stations in South London

Southern Railway stations in South London The south London area stations of Southern Region of British Railways and its constituents tend to be somewhat neglected, perhaps due to the prevalent suburban electric services, but comprised some fine examples of former company architecture. The following pictures were all taken in August 1973; a few of the sites have since disappeared, many others surely much modernised by now, and some have even been nicely restored...... First, we look at the former South Eastern Railway branch line from Purley to Caterham. Here is Kenley, whose cottage-style station house with very steep-pitched roof and gothic detailing is now a listed building, but privately owned. It dates from the construction of the Caterham Railway in 1856 and is by architect Richard Whittall. Below is Whyteleafe, (left) down side waiting room and footbridge, and the signal box and level crossing at Whyteleafe South...... The signalbox nameboard shows that the station had been re-signed with modern British Rail white enamel plates; in late 1972 I found one of the much more attractive 1950-era station nameplates for sale in an antique shop near Paddington station, for the pricely sum of £2.50p. In contrast the teminus station building at Caterham still displayed its “Southern Electric” enamelware...... Here are two more views at Caterham, with the SE&CR wooden signalbox at right...... Moving on to Anerley, this is an ex London Brighton & South Coast Railway station on its line from London Bridge to West Croydon, just to the north of Norwood Junction. At least part of the main building is thought to date from the line opening in 1839. -

The Operator's Story Appendix

Railway and Transport Strategy Centre The Operator’s Story Appendix: London’s Story © World Bank / Imperial College London Property of the World Bank and the RTSC at Imperial College London Community of Metros CoMET The Operator’s Story: Notes from London Case Study Interviews February 2017 Purpose The purpose of this document is to provide a permanent record for the researchers of what was said by people interviewed for ‘The Operator’s Story’ in London. These notes are based upon 14 meetings between 6th-9th October 2015, plus one further meeting in January 2016. This document will ultimately form an appendix to the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’ piece Although the findings have been arranged and structured by Imperial College London, they remain a collation of thoughts and statements from interviewees, and continue to be the opinions of those interviewed, rather than of Imperial College London. Prefacing the notes is a summary of Imperial College’s key findings based on comments made, which will be drawn out further in the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’. Method This content is a collation in note form of views expressed in the interviews that were conducted for this study. Comments are not attributed to specific individuals, as agreed with the interviewees and TfL. However, in some cases it is noted that a comment was made by an individual external not employed by TfL (‘external commentator’), where it is appropriate to draw a distinction between views expressed by TfL themselves and those expressed about their organisation. -

Investigation Into Reliability of the Jubilee Line

Investigation into Reliability: London Underground Jubilee Line An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science By Jack Arnis Agolli Marianna Bailey Errando Berwin Jayapurna Yiannis Kaparos Date: 26 April 2017 Report Submitted to: Malcolm Dobell CPC Project Services Professors Rosenstock and Hall-Phillips Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, see http://www.wpi.edu/Academics/Projects. Abstract Metro systems are often faced with reliability issues; specifically pertaining to safety, accessibility, train punctuality, and stopping accuracy. The project goal was to assess the reliability of the London Underground’s Jubilee Line and the systems implemented during the Jubilee Line extension. The team achieved this by interviewing train drivers and Transport for London employees, surveying passengers, validating the stopping accuracy of the trains, measuring dwell times, observing accessibility and passenger behavior on platforms with Platform Edge Doors, and overall train performance patterns. ii Acknowledgements We would currently like to thank everyone who helped us complete this project. Specifically we would like to thank our sponsor Malcolm Dobell for his encouragement, expert advice, and enthusiasm throughout the course of the project. We would also like to thank our contacts at CPC Project Services, Gareth Davies and Mehmet Narin, for their constant support, advice, and resources provided during the project. -

Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2016 Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945 Danielle K. Dodson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.339 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dodson, Danielle K., "Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--History. 40. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/40 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Igniting Change and Building on the Spirit of Dalston As One of the Most Fashionable Postcodes in London. Stunning New A1, A3

Stunning new A1, A3 & A4 units to let 625sq.ft. - 8,000sq.ft. Igniting change and building on the spirit of Dalston as one of the most fashionable postcodes in london. Dalston is transforming and igniting change Widely regarded as one of the most fashionable postcodes in Britain, Dalston is an area identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London. It is located directly north of Shoreditch and Haggerston, with Hackney Central North located approximately 1 mile to the east. The area has benefited over recent years from the arrival a young and affluent residential population, which joins an already diverse local catchment. , 15Sq.ft of A1, A3000+ & A4 commercial units Located in the heart of Dalston and along the prime retail pitch of Kingsland High Street is this exciting mixed use development, comprising over 15,000 sq ft of C O retail and leisure space at ground floor level across two sites. N N E C T There are excellent public transport links with Dalston Kingsland and Dalston Junction Overground stations in close F A proximity together with numerous bus routes. S H O I N A B L E Dalston has benefitted from considerable investment Stoke Newington in recent years. Additional Brighton regeneration projects taking Road Hackney Downs place in the immediate Highbury vicinity include the newly Dalston Hackney Central Stoke Newington Road Newington Stoke completed Dalston Square Belgrade 2 residential scheme (Barratt Road Haggerston London fields Homes) which comprises over 550 new homes, a new Barrett’s Grove 8 Regents Canal community Library and W O R Hoxton 3 9 10 commercial and retail units. -

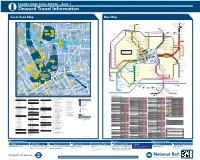

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 1 35 Wellington OUTRAM PLACE 259 T 2 HAVELOCK STREET Caledonian Road & Barnsbury CAMLEY STREET 25 Square Edmonton Green S Lewis D 16 L Bus Station Games 58 E 22 Cubitt I BEMERTON STREET Regent’ F Court S EDMONTON 103 Park N 214 B R Y D O N W O Upper Edmonton Canal C Highgate Village A s E Angel Corner Plimsoll Building B for Silver Street 102 8 1 A DELHI STREET HIGHGATE White Hart Lane - King’s Cross Academy & LK Northumberland OBLIQUE 11 Highgate West Hill 476 Frank Barnes School CLAY TON CRESCENT MATILDA STREET BRIDGE P R I C E S Park M E W S for Deaf Children 1 Lewis Carroll Crouch End 214 144 Children’s Library 91 Broadway Bruce Grove 30 Parliament Hill Fields LEWIS 170 16 130 HANDYSIDE 1 114 CUBITT 232 102 GRANARY STREET SQUARE STREET COPENHAGEN STREET Royal Free Hospital COPENHAGEN STREET BOADICEA STREE YOR West 181 212 for Hampstead Heath Tottenham Western YORK WAY 265 K W St. Pancras 142 191 Hornsey Rise Town Hall Transit Shed Handyside 1 Blessed Sacrament Kentish Town T Hospital Canopy AY RC Church C O U R T Kentish HOLLOWAY Seven Sisters Town West Kentish Town 390 17 Finsbury Park Manor House Blessed Sacrament16 St. Pancras T S Hampstead East I B E N Post Ofce Archway Hospital E R G A R D Catholic Primary Barnsbury Handyside TREATY STREET Upper Holloway School Kentish Town Road Western University of Canopy 126 Estate Holloway 1 St. -

List of Accessible Overground Stations Grouped by Overground Line

List of Accessible Overground Stations Grouped by Overground Line Legend: Page | 1 = Step-free access street to platform = Step-free access street to train This information was correct at time of publication. Please check Transport for London for further information regarding station access. This list was compiled by Benjamin Holt, Transport for All 29/05/2019. Canada Water Step-free access street to train East London line Haggerston Step-free access street to platform Dalston Hoxton Step-free access street to platform Junction - New New Cross Step-free access street to platform Cross Canada Water Step-free access street to platform Clapham High Street Step-free access street to platform Denmark Hill Step-free access street to platform Haggerston Step-free access street to platform Hoxton Step-free access street to platform Peckham Rye Step-free access street to platform Queens Road Peckham Step-free access street to platform East London line Rotherhithe Step-free access street to platform Shadwell Step-free access street to platform Dalston Canada Water Step-free access street to train Junction - Canonbury Step-free access street to train Clapham Crystal Palace Step-free access street to platform Junction Dalston Junction Step-free access street to train Forest Hill Step-free access street to platform Haggerston Step-free access street to train Highbury & Islington Step-free access street to platform Honor Oak Park Step-free access street to platform Hoxton Step-free access street to train New Cross Gate Step-free access street to platform -

Heathrow Expansion

Briefing Sheet Key Politicians Ministers and MPs, MEPS and GLA Members Addresses Ministers and MPs can be contacted at the House of Commons, London SW1A 0AA; Lords at the House of Lords, London SW1A 0PW; MEPs at 2 Queen Anne's Gate, London SW1H 9AA; GLA Members at City Hall, The Queen's Walk, London SE1 2AA. Key Ministers: Douglas Alexander MP, Secretary of State at the Department for Transport; Gillian Merron MP, Under-Secretary of State, responsible for Aviation; David Milliband MP, Secretary of State at the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA); Key MPs: Martin Linton, Lab, Battersea; Andrew Mackay, Con, Bracknell; Ann Keen, Lab, Brentford & Isleworth; Mark Field, Con, City of London & Westminster; Malcolm Wicks, Lab, Croydon North; Stephen Pound, Lab, Ealing North; Piara Khabra, Lab, Ealing Southall; Andy Slaughter, Lab, Ealing Acton & Shepherd's Bush; Ian Taylor, Con, Esher & Walton; Alan Keen, Lab, Feltham & Heston; Greg Hands, Con, Hammersmith & Fulham; John McDonnell, Lab, Hayes & Harlington; Malcolm Rifkind, Con, Kensington & Chelsea; Edward Davey, Lib Dem, Kingston & Surbiton; Theresa May, Con, Maidenhead; Justine Greening, Con Putney; Susan Kramer, Lib Dem, Richmond Park; Fiona MacTaggart, Lab, Slough; David Wilshire, Con, Spelthorne; Keith Hill, Lab, Streatham; Sadiq Khan, Lab, Tooting; Vincent Cable; Lib Dem, Twickenham; John Randall, Con, Uxbridge; Kate Hoey, Lab, Vauxhall; Stephen Hammond, Con, Wimbledon; Adam Afriyie, Con, Windsor; Tessa Jowell, Lab, West Norwood and Dulwich; Harriet Harman, Camberwell -

The Impact of the Jubilee Line Extension of the London Underground Rail Network on Land Values

The Impact of the Jubilee Line Extension of the London Underground Rail Network on Land Values Stephen R. Mitchell and Anthony J. M. Vickers © 2003 Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper The findings and conclusions of this paper are not subject to detailed review and do not necessarily reflect the official views and policies of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Please do not photocopy without permission of the authors. Contact the authors directly with all questions or requests for permission. Lincoln Institute Product Code: WP03SM1 Abstract Using U.K. Government published property value data, an analysis of the impact of a major extension to London’s subway network during the late 1990s was undertaken to establish whether value uplift attributable to new transport infrastructure could finance such projects. Different approaches were used for commercial and residential land. Data deficiencies were a major problem and it was not possible to combine the results. Commercial land value uplift could not be quantified. For residential land the total figure (£9 billion) for the Jubilee Line Extension (JLE) was based on calculations for five stations. This could be several billion pounds higher or lower. The JLE actually cost £3.5 billion. Although a method of spatially analyzing commercial ratable values was developed, data deficiencies prevented modeling a true ‘landvaluescape’. It was concluded that this did not significantly affect the accuracy of results. The matter of how individual land value increments could be fairly assessed and collected was not pursued but some recommendations were made as to how U.K. property data systems might be improved to support such fiscal instruments. -

Tfl Interchange Signs Standard

Transport for London Interchange signs standard Issue 5 MAYOR OF LONDON Transport for London 1 Interchange signs standard Contents 1 Introduction 3 Directional signs and wayfinding principles 1.1 Types of interchange sign 3.1 Directional signing at Interchanges 1.2 Core network symbols 3.2 Directional signing to networks 1.3 Totem signs 3.3 Incorporating service information 1.3 Horizontal format 3.4 Wayfinding sequence 1.4 Network identification within interchanges 3.5 Accessible routes 1.5 Pictograms 3.6 Line diagrams – Priciples 3.7 Line diagrams – Line representation 3.8 Line diagrams – Symbology 3.9 Platform finders Specific networks : 2 3.10 Platform confirmation signs National Rail 2.1 3.11 Platform station names London Underground 2.2 3.12 Way out signs Docklands Light Railway 2.3 3.13 Multiple exits London Overground 2.4 3.14 Linking with Legible London London Buses 2.5 3.15 Exit guides 2.6 London Tramlink 3.16 Exit guides – Decision points 2.7 London Coach Stations 3.17 Exit guides on other networks 2.8 London River Services 3.18 Signing to bus services 2.9 Taxis 3.19 Signing to bus services – Route changes 2.10 Cycles 3.20 Viewing distances 3.21 Maintaining clear sightlines 4 References and contacts Interchange signing standard Issue 5 1 Introduction Contents Good signing and information ensure our customers can understand Londons extensive public transport system and can make journeys without undue difficulty and frustruation. At interchanges there may be several networks, operators and line identities which if displayed together without consideration may cause confusion for customers. -

The Environmental Statement

The Environmental Statement The Environmental Statement and this Non-Technical Summary have been prepared by Environmental Resources Management (ERM), on behalf of DLRL. ERM is an independent environmental consultancy with extensive experience of undertaking Environmental Impact Assessments of transport infrastructure schemes. Copies of the Environmental Statement are available for inspection at the following locations: Docklands Light Railway Ltd Canning Town Library PO Box 154, Castor Lane, Poplar, Barking Road, Canning Town, London E14 0DX London E16 4HQ (Opening Hours: 9.00am-5.00pm Mondays to Fridays) (Opening Hours: Monday 9.30am-5.30pm, Tuesday 9.30am- 5.30pm, Wednesday Closed, Thursday 1.00-8.00pm, Friday London Borough of Newham 9.30am-5.30pm, Saturday 9.30am-5.30pm, Sunday Closed) Environmental Department, 25 Nelson Street, East Ham, London E6 2RP Custom House Library (Opening Hours: 9.00am-5.00pm Mondays to Fridays) Prince Regent Lane, Custom House, London E16 3JJ Bircham Dyson Bell (Opening Hours: Monday 9.30am-5.30pm, Tuesday 9.30am- Solicitors and Parliamentary Agents, 5.30pm, Wednesday Closed, Thursday 1.00-8.00pm, Friday 50 Broadway, Westminster, London SW1H 0BL Closed, Saturday 9.30am-5.30pm, Sunday Closed) (Opening Hours: 9.30am-5.30pm Mondays to Fridays) North Woolwich Library Hackney Central Library Storey School, Woodman Street¸ Technology and Learning Centre, North Woolwich, London E16 2LS 1 Reading Lane, London E8 1GQ (Opening Hours: Monday 9.30am-1.30pm and 2.30pm-5.30pm, (Opening Hours: Monday 9.00am-8.00pm, Tuesday