Is Tanning Related to Need for Acceptance? Erica Bewley, Natalie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf Prikaz / Ispis

Utopia and Political Theology No. 2 - Year 5 06/2015 - LT.6 Zoran Ferić - Tomislav Kuzmanović, University of Zadar, Croatia Alone by the Sea 1. At first the island is just a sign on a yellow board with a drawing of a vessel and the letters saying “Car Ferry,” then it is a grayish silhouette in the blue of the sea, and then, later still, an acquaintance working on the ferry, who just nods briefly in greeting. Jablanac, ferry port, its pleasant lobby, and then, from the upper deck, a giant rock approaching. That is the object of a year-long desire: the moment of stepping off the boat and smelling the rosemary, diesel and sheep droppings, seeing the sharp rocks looking at the Strait of Senj, coarse limestone in sharp opposition to the signs that say: Benvenuti, Welcome, Willkommen! At home, on the terrace, in the shade of the oleander, there’s no wish to eat. Only swimming trunks are put on and then, barefoot, without a towel or sun-tanning lotion, off to the beach. “Why won’t you eat something?” grandma asks. She knows that there’s an exciting world waiting out there, but she knows nothing of the details. All friends went on a boat trip. And suddenly one step from the shade of a path covered with oleanders and acacias leads into the burning sun of the afternoon. The light screams, just like children in the water, just like white objects that radiate as if there are some powerful light bulbs within. The feeling of freedom of someone who has just arrived in a foreign place and can now do anything. -

Spa-Broschuere-1521556030.Pdf

REJUVENATE YOUR SENSES Dear Valued Guest, I would like to personally welcome you to the Myconian Collection Spas. All of our 7 Spas are a magical place of relax- ation and of nursing mind, body and soul. We aim to offer you a personal journey that is dedicate to revitalising your body, mind and soul. With a carefully curated menu, inspired by the purest resources from oceans and earth, to allow you to experience the wonders of well-being with methods ascertained since antiquity up to nowadays. Your skin and your well-being lies at the heart of what we do and we have joined forces with ELEMIS, one of the world’s leading and premium SPA brands, as well as St.Barths with products of exceptional quality. Our treatments are designed to respect the body’s complex physiology, and to work in natural synergy with the skin, body and mind. Every treatment is specifically designed to offer a unique experience, using powerful massage sequenc- es and the most potent actives available in the world today. Our highly trained therapists make it personal. They look, they listen, tune in to you. Our secret dwells in the wealth of the sea, the extracts of plants, flowers and botanicals and to the expert teqhnique we apply for every therapy. Transformative results. Unique Experiences. Welcome to the Myconian Spas. Eleftheria Karapiperaki Director of Spas at Myconian Collection MYCONIAN VILLA COLLECTION SIGNATURE TREATMENTS Myconian Signature Escape 1hr 20mins This treatment is designed to hydrate and nourish your skin. Body Wrap & Relaxing Full body Massage Express Facial Treatment Myconian Signature Journey 1hour 50mins An interactive experiment of the senses. -

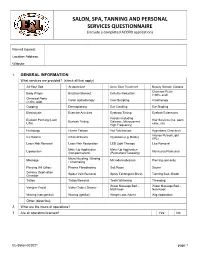

SALON, SPA, TANNING and PERSONAL SERVICES QUESTIONNAIRE (Include a Completed ACORD Application)

SALON, SPA, TANNING AND PERSONAL SERVICES QUESTIONNAIRE (include a completed ACORD application) Named Insured: Location Address: Website: 1. GENERAL INFORMATION What services are provided? (check all that apply) 24-Hour Spa Acupuncture Acne Scar Treatment Beauty School/ Classes Chemical Peels Body Wraps Brazilian Blowout Cellulite Reduction (<30% acid) Chemical Peels Colon Hydrotherapy Cool Sculpting Cryotherapy (>30% acid) Cupping Dermaplaning Ear Candling Ear Stapling Electrolysis Exercise Activities Eyebrow Tinting Eyelash Extensions Facials (including Eyelash Perming (Lash Hair Services (cut, perm, Eyelash Tinting Galvanic, Microcurrent, Lifts) color, etc) High Frequency) Herbology Henna Tattoos Hot Tub/Jacuzzi Hyperbaric Chambers Intense Pulsed Light Ice Rooms Infrared Sauna Injections (e.g. Botox) (IPL) Laser Hair Removal Laser Hair Restoration LED Light Therapy Lice Removal Make-Up Application Make-Up Application Liposuction Manicures/Pedicures (non-permanent) (Permanent/Tattooing) Micro Needling / Blading Massage Microdermabrasion Piercing (ear only) / Channeling Piercing (All Other) Plasma Fibroblasting Salt Room Sauna Sensory Deprivation Spider Vein Removal Spray Tanning/Air Brush Tanning Bed / Booth Chamber Tattoo Tattoo Removal Teeth Whitening Threading Water Massage Bed – Water Massage Bed – Vampire Facial Vichy (Table) Shower Mall Kiosk Non Kiosk Waxing (non-genital) Waxing (genital) Weight Loss Advice Wig Application Other (describe): 2. What are the hours of operations? 3. Are all operators licensed? Yes No EL-Salon-022021 page 1 HAIR, SKIN, AND NAIL SERVICES N/A 1. Provide the total number of all operators (include employees, owners, independent contractors or others providing services) Full Time Part Time Full Time Part Time Employee Type (20+ hrs/ (<20 hrs/ Employee Type (20+ hrs/ (<20 hrs/ week) week) week) week) Beauticians/Barbers Aesthetician Nail Technicians Massage Therapists Electrologists (include those Other (describe): performing chemical peels & microdermabrasion) 2. -

To Tan Or Not to Tan? Here Are the Facts!

TO TAN OR NOT TO TAN? HERE ARE THE FACTS! WHO GETS SKIN CANCER? WHAT ARE THE FACTS ABOUT Skin cancer is the most common cancer in the United States. TANNING AND TANNING BEDS? It affects men and women, oungy and old. Over 90 percent of • Persons who first use tanning beds before the age of 35 skin cancers are caused by exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light, increase their risk of melanoma by 75 percent. the same type of light that makes people tan. Skin cancer can be prevented by taking a few safety measures, such • Tanning beds are in the same cancer risk category as as wearing sunscreen, staying in the shade AND avoiding arsenic, tobacco smoke, the hepatitis B virus and artificial sources of UV light, such as tanning beds. radioactive plutonium. • There is no such thing as a “safe tan.” A base tan does WHAT IS SKIN CANCER? not protect from sunburn. In fact, a tan is the body’s natural response to UV rays and indicates that the skin Melanomas and nonmelanomas are the two categories of has been damaged. skin cancer. • Tanning beds use the same UV light as sunlight. Nonmelanomas (usually called basal cell and squamous cell Just 20 minutes in a tanning booth is the same as cancers) are the most common cancers of the skin. They are spending an entire day at the beach. also the easiest to treat if found early. These cancers are more common in older people. • UV rays break down the elasticity of the skin, causing premature aging, fine lines and wrinkles. -

5. Physical Therapies

70 Health guidelines for personal care and body art industries 5. Physical therapies Under the current Health Act (1958) the following practices do not require registration with local government. The information provided relates to general hygiene in minimising the risk and the spread of potentially harmful microorganisms that may lead to infection. Adoption of the outlined information is encouraged. 5.1 Massage In performing various massage therapies, the operator needs to assess all possible infection risks and to consult their professional organisation. See the following sections for appropriate procedures to reduce the potential for the transmission of infection: • hands—see part A, section 3.3 • surfaces—see part A, section 4.2.2 • linen—see part A, section 2.3.5 • oils/creams—see part A, section 2.5. 5.2 Solaria Guidelines for the installation, maintenance and operation of solaria are outlined in AS/NZS 2635:2002 Solaria for cosmetic purposes. The standard seeks to increase the levels of safety associated with the use of solaria. The Department of Human Services recommends compliance. The following are key requirements of the standard. 5.2.1 Age limit It is recommended that an operator does not allow an individual under the age of 18 years to use a sun-tanning unit without parental or guardian consent. Any individual under the age of 15 years is strictly not permitted. 5.2.2 Warning notices Commercial premises should place one or more notices (of A4-size paper) presenting the following information (in legible print) within the immediate view of every client entering the premises and in each sun-tanning unit cubicle. -

Georgia Department of Public Health Environmental Health Section

Georgia Department of Public Health Environmental Health Section Georgia Registered Tanning Facilities (by County) To search for a facility, Click Ctrl + F (or go to Edit, Find) and search by county name and/or facility name. Bacon Salon Bella Barharbro, LLC dba Athletic Club Anytime Fitness 3975 Arkwright Road, Ste. 3, Macon, 31210 106 Somerset Place, Carrollton, 30116 1020 S Pierce Street , Alma, 31510 478/477-4665 770 832-1491 912 632-8223 Sun Villa LLC Coconuts Shop & Tan Simply Tan 5451 Bowman Road, Suite 430, Macon, 31210 375 Hwy 78 W. A Temple, Temple, 30179 1008 S Pierce Street , Alma, 31510 478-254-8511 678-758-0177 912-632-0557 Bleckley Haven West Baldwin Destiny Fitness of Cochran 1321 Lovvorn Road, Carrollton, 30117 Magnolia Park SH, LLC 135 N 2nd St, Cochran, 31014 678-321-1999 529 W ByPass NW, Milledgeville, 31061 478-271-5854 Panama Tan Inc 478/451-0077 Brantley 104 Hwy 61 Connector, Villa Rica, 30180 Sun Brushed Tanning Salon LS Harris LLC DBA Iron House Gym 770/459-9100 128 S Wayne St., Milledgeville, 31061 13299 Cleveland St. W Ste. 1, Nahunta, 31516 Private Beach Tanning 478-295-3454 912-462-4766 628 Hwy 61, Villa Rica, 30180 The Bellamy at Milledgeville Main Street Salon 770/456-1965 145 South Irwin Street, Milledgeville, 31061 9630 Main St. South, Nahunta, 31553 Sta Fit & Tan 478/457-0004 912-462-4247 105 West Perrennial, Temple, 30179 Barrow Bulloch 770 562-5552 Chateau Island Tanning, LLC Eagle Clips Toe 2 Toe Fitness 3740 Village Way Ste. C, Braselton, 30517 1550 Chandler Center Suite G, Statesboro, 30458 753 Industrial Blvd, Villa Rica, 30180 770-307-0076 912-871-7105 770 456-0754 Luxury Nail Spa Salon Hair Studio 101 Catoosa 111 E May Street, Suite 80, Winder, 30680 13 South Main, Statesboro, 30458 Darryl's California Concept 770-868-8880 912 764-6442 17 Whisperwood Court, Ringgold, 30736 RDJ Capital GAT-1 Paw Print Ent, LLC dba Portal House of Styles 706 937-3574 217 E May St, Winder, 30680 27180 Highway 80 W , Portal, 30450 Fort Lake Tanning 770/307-6865 912/865-2094 667 Battlefield Pkwy, Ft. -

Managing Symptoms of Polycythemia Vera (Pv)

MANAGING SYMPTOMS OF POLYCYTHEMIA VERA (PV) 800-813-HOPE (4673) [email protected] www.cancercare.org If you are coping with polycythemia vera (PV), it is important to keep track of your symptoms and how they affect your daily activities. Over time, this will help your health care team know how to best manage this long-term diagnosis so that you can experience the best quality of life. HERE ARE SOME COMMON SYMPTOMS OF PV, ALONG WITH PRACTICAL STEPS YOU CAN TAKE TO COPE WITH THEM: Fatigue. Start a gradual exercise program. Walking can improve your strength and energy level and can also improve blood flow, which decreases the risk of blood Headaches and vision problems; clots. Exercising and stretching burning, redness or swelling of the the legs and ankles improves hands and feet. Aspirin may help blood circulation. with these symptoms. Your doctor can determine the dosage that is Gout. Signs of gout include best for you. swelling in one or many joints or pain in the big toe. Your doctor Emotional distress. Sometimes, can prescribe various medications talking with a family member, to control a flare-up of gout; friend or loved one can help. You allopurinol (Zyloprim and others) may also benefit from the help of a is often prescribed to prevent professional oncology social worker. future attacks. It’S IMPORTANT TO FOCUS ON Itching. To keep your skin from YOUR OVERALL HEALTH, WHICH drying out and becoming itchy, WILL HELP YOU BETTER MANAGE lower the temperature of your YOUR PV: shower or bath water, especially Exercise and eat a healthy diet to in the winter. -

The Darker Side of Tanning

The Darker Side of Tanning Public health experts and medical professionals are continuing to warn people about the dangers of ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun, tanning beds, and sun lamps. Two types of ultraviolet radiation are Ultraviolet A (UVA) and Ultraviolet B (UVB). UVB has long been associated with sunburn while UVA has been recognized as a deeper penetrating radiation. Although it's been known for some time that too much UV radiation can be harmful, new information may now make these warnings even more important. Some scientists have suggested recently that there may be an association between UVA radiation and malignant melanoma, the most serious type of skin cancer. What are the dangers of tanning? UV radiation from the sun, tanning beds, or from sun lamps may cause skin cancer. While skin cancer has been associated with sunburn, moderate tanning may also produce the same effect. UV radiation can also have a damaging effect on the immune system and cause premature aging of the skin, giving it a wrinkled, leathery appearance. But isn't getting some sun good for your health? People sometimes associate a suntan with good health and vitality. In fact, just a small amount of sunlight is needed for the body to manufacture vitamin D. It doesn't take much sunlight to make all the vitamin D you can use certainly far less than it takes to get a suntan! Are people actually being harmed by sunlight? Yes. The number of skin cancer cases has been rising over the years, and experts say that this is due to increasing exposure to UV radiation from the sun, tanning beds, and sun lamps. -

Georgia Department of Public Health Environmental Health Section

Georgia Department of Public Health Environmental Health Section Georgia Registered Tanning Facilities (by County) To search for a facility, Click Ctrl + F (or go to Edit, Find) and search by county name and/or facility name. Bacon Main Street Salon Chatham Anytime Fitness 9630 Main St. South, Nahunta, 31553 24 Hour Family Fitness Center 1020 S Pierce Street, Alma, 31510 912-462-4247 14045 Abercorn St., Unit 1536, Savannah, 31419 912 632-8223 Bulloch 912/920-7734 Baldwin Breckenridge Group Statesboro Georgia LLC Coastal Fitness, LLC Arcadia on the River 17358 Highway 67 #100, Statesboro, 30458 3609 Ogeechee Blvd. Suite C, Savannah, 31405 478 Oconee Bend, Milledgeville, 31061 912-681-9703 912-231-3733 478-253-4430 Eagle Clips Fitness Hub DBA Zoo Health Club Magnolia Park SH, LLC 1550 Chandler Center Suite G, Statesboro, 30458 301 mall Way, Savannah, 31406 529 W ByPass NW, Milledgeville, 31061 912-871-7105 912 712 3100 478/451-0077 Paw Print Ent, LLC dba Portal House of Styles Savannah Fitness Group dba Anytime Fitness Banks 27180 Highway 80 W , Portal, 30450 119 Charlotte Rd, Suite F, Savannah, 31410 Titanz Fitness of Northeast Georgia 912/865-2094 912 897-1499 280 Banks Crossing Drive, Commerce, 30529 Vesper Forum at Statesboro,LLC Shoreline Fitness, LLC 770 369 4691 831 S. Main Street, Statesboro, 30458 1100 Eisenhower Drive, Savannah, 31406 Barrow 912-489-3676 603-601-0611 Coastal Tan LLC Butts Chattooga 111 W May St, Winder, 30680 RPM Property Services Inc. DBA Barbell Nutrition Center Raw Fitness LLC 770/586-5304 36 Oak Street, Jackson, 30233 14245 Hwy 27, Trion, 30753 S H Capital GAT-1, LLC 4702515093 706-857-8881 217 E. -

Sun Damage Not Glamourous (Click on the Page Numbers to Go Directly to the Section) Blame It on Coco

Volume 8 Number 6 May 2011 Stay safe. Stay healthy. Stay current. Lead Story Inside this month’s issue of Comfort Zone: Sun damage not glamourous (Click on the page numbers to go directly to the section) Blame it on Coco. Coco Chanel, that is. Making Headlines n the 1920s, this famous fashion Pages 2-3 designer turned suntanned skin New therapy for MS into a fashion statement. I Babies burdened by rotovirus Sunbathing became a ritual, and people flocked to the beaches to Symptoms of glaucoma "catch some rays." This ritual What’s causing my headache continues today. Tanned skin is still seen as fashionable, healthy, and Tips For Supervisors luxurious. In 1962, SPF rated sunscreen was Pages 4-5 introduced. In 1971, Mattel Restless nights, restless days introduced Malibu Barbie, which had Solidify your soft skills tanned skin, sunglasses, and her very Safety starts on day one own bottle of sun tanning lotion. In Swallowing disorders 1978, tanning beds appeared. In the US, the tanning business is now a five-billion dollar industry. There are Health & Safety Round up an estimated 50,000 outlets for before the age of 20. Most UVB rays Page 6 tanning. However, although tanned are absorbed by the ozone layer, but Vehicle ejections kill skin is still a status symbol, awareness enough of these rays pass through to Communication disorders of what the sun’s rays can do to our cause serious damage. skin is very important. UVC rays are the most dangerous, Seminars Sunlight contains three types of but fortunately, these rays are blocked ultraviolet rays: UVA, UVB, and by the ozone layer and don't reach the Health and Safety Minute UVC. -

Shabbos 095.Pub

י"ז סיון תשפ“ Tues, Jun 9 2020 OVERVIEW of the Daf Gemara GEM 1) Grooming activities (cont.) Milking a Cow —Which Melacha Is It? חולב חייב משום מפרק R’ Avahu in the name of R’ Yosi the son of R’ Chanina explains that one who applies paint to her eyes violates the pro- hibition against dyeing, and one who fixes or braids her hair R ashi explains that the melacha involved in milking an animal Rashi also quotes others who say that it fits into .דש – violates the prohibition against building. is threshing which is when something is cut off ,קוצר- R’ Shimon ben Elazar rules that liability for grooming is the category of harvesting from its source from where it nurtured. Rashi rejects this explana- when a woman grooms another, but a woman who grooms her- tion, though, because harvesting is only when something is at- self she is not liable. tached to the ground and it is then cut off from its source. Milk is 2) Toldos not attached to its source in this manner. A Baraisa records a dispute whether different activities vio- Tosafos, questions Rashi’s interpretation that milking falls late a Torah prohibition or only a Rabbinic enactment. into the category of threshing. Threshing, Tosafos maintains, is 3) Removing loaves of honey from a honeycomb only applicable by commodities which grow from the ground, and R’ Elazar provides the source for R’ Eliezer’s ruling that re- milk is not in this class. Therefore, Tosafos claims that milking an The udder is softened .ממחק – moving loaves of honey from a honeycomb violates a Torah animal is the melacha of smoothing prohibition. -

Skin Cancer: Increasing Risk in Idaho Facts About: Skin Cancer

Offi ce of Air and Radiation (6205J) EPA-430-F-09-062 May 2009 facts about: Skin Cancer IDAHO Skin cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in the United States.1-4 This fact sheet presents statistics about skin Melanoma Death Rates, 2001–200514 cancer for Idaho and the United States as a whole. All Races, Both Sexes, All Ages skin cancer: Increasing Risk in Idaho ■ Sunburns. A 2004 survey found that 48.5% of white adults in Idaho had at least one sunburn in the past year.5 Sunburns are a signifi cant risk factor for the development of skin cancer.6-8 ID ■ New Cases of Melanoma. The annual rate of new melanoma diagnoses— responsible for 75% of all skin cancer deaths—was 34% higher in Idaho than the national average and was the 7th highest in the U.S. from 2001-2005.10,11 An estimated 360 state residents were diagnosed with melanoma in 2008.2 ■ Among whites—who are at the highest risk for melanoma—Idaho had the 11th highest melanoma incidence rate in the U.S. from 2001-2005.12 ■ New diagnoses of melanoma increased at a rate of about 3.6% per year in 9 Melanoma Deaths per Year Idaho from 1975 to 2006. The rate of increase was higher for males (4.2% per per 100,000 People 9 year) than for females (2.8% per year). 1.6–2.0 2.1–2.5 2.6–3.0 3.1–3.4 ■ Deaths from Melanoma. Idaho had the highest melanoma death rate nationally 13 from 2001-2005—26% higher than the U.S.