Repetitive Reduplication in Yurok and Karuk: Semantic Effects of Contact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward the Reconstruction of Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan. Part 3: the Algonquian-Wakashan 110-Item Wordlist

Sergei L. Nikolaev Institute of Slavic studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow/Novosibirsk); [email protected] Toward the reconstruction of Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan. Part 3: The Algonquian-Wakashan 110-item wordlist In the third part of my complex study of the historical relations between several language families of North America and the Nivkh language in the Far East, I present an annotated demonstration of the comparative data that was used in the lexicostatistical calculations to determine the branching and approximate glottochronological dating of Proto-Algonquian- Wakashan and its offspring; because of volume considerations, this data could not be in- cluded in the previous two parts of the present work and has to be presented autonomously. Additionally, several new Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan and Proto-Nivkh-Algonquian roots have been set up in this part of study. Lexicostatistical calculations have been conducted for the following languages: the reconstructed Proto-North Wakashan (approximately dated to ca. 800 AD) and modern or historically attested variants of Nootka (Nuuchahnulth), Amur Nivkh, Sakhalin Nivkh, Western Abenaki, Miami-Peoria, Fort Severn Cree, Wiyot, and Yurok. Keywords: Algonquian-Wakashan languages, Nivkh-Algonquian languages, Algic languages, Wakashan languages, Chimakuan-Wakashan languages, Nivkh language, historical phonol- ogy, comparative dictionary, lexicostatistics. The classification and preliminary glottochronological dating of Algonquian-Wakashan currently remain the same as presented in Nikolaev 2015a, Fig. 1 1. That scheme was generated based on the lexicostatistical analysis of 110-item basic word lists2 for one reconstructed (Proto-Northern Wakashan, ca. 800 A.D.) and several modern Algonquian-Wakashan lan- guages, performed with the aid of StarLing software 3. -

Some Morphological Parallels Between Hokan Languages1

Mikhail Zhivlov Russian State University for the Humanities; School for Advanced Studies in the Humanities, RANEPA (Moscow); [email protected] Some morphological parallels between Hokan languages1 In this paper I present a detailed analysis of a number of morphological comparisons be- tween the branches of the hypothetical Hokan family. The following areas are considered: 1) subject person/number markers on verbs, as well as possessor person/number markers on nouns, 2) so-called ‘lexical prefixes’ denoting instrument and manner of action on verbs, 3) plural infixes, used with both nouns and verbs, and 4) verbal directional suffixes ‘hither’ and ‘thither’. It is shown that the respective morphological parallels can be better accounted for as resulting from genetic inheritance rather than from areal diffusion. Keywords: Hokan languages, Amerindian languages, historical morphology, genetic vs. areal relationship 0. The Hokan hypothesis, relating several small language families and isolates of California, was initially proposed by Dixon and Kroeber (1913) more than a hundred years ago. There is still no consensus regarding the validity of Hokan: some scholars accept the hypothesis (Kaufman 1989, 2015; Gursky 1995), while others view it with great skepticism (Campbell 1997: 290–296, Marlett 2007; cf. a more positive assessment in Golla 2011: 82–84, as well as a neutral overview in Jany 2016). My own position is that the genetic relationship between most languages usually subsumed under Hokan is highly likely, and that the existence of the Ho- kan family can be taken as a working hypothesis, subject to further proof or refutation. The goal of the present paper is to draw attention to several morphological parallels be- tween Hokan languages. -

Published in Papers of the Twenty-Third Algonquian Conference, 1992, Edited by William Cowan

Published in Papers of the Twenty-Third Algonquian Conference, 1992, edited by William Cowan. Ottawa: Carleton University, pp. 119-163 A Comparison of the Obviation Systems of Kutenai and Algonquian Matthew S. Dryer SUNY at Buffalo 1. Introduction In recent years, the term ‘obviation’ has been applied to phenomena in a variety of languages on the basis of perceived similarity to the phenomenon in Algonquian languages to which, I assume, the term was originally applied. An example of a descriptive use of the term occurs in Dayley (1989: 136), who applies the terms ‘obviative’ and ‘proximate’ to two categories of demonstratives in Tümpisa Shoshone, the obviative category being used to introduce new information or to reference given participants which are nontopics, the proximate category for topics. But unlike the obviative and proximate categories of Algonquian languages, the Shoshone categories for which Dayley uses the terms are categories only of a class of words he calls ‘demonstratives’, and are not inflectional categories of nouns or verbs. Similarly, Simpson and Bresnan (1983) use the term ‘obviation’ to refer to a system in Warlpiri in which certain nonfinite verbs occur in forms that indicate that their subjects are nonsubjects in the matrix clause. These phenomena in non-Algonquian languages to which the term ‘obviation’ has been applied may bear some remote resemblance to the Algonquian phenomenon, but I suspect that most Algonquianists examining them would conclude that the resemblance is at best a remote one. The purpose of this paper is to describe an obviation system in Kutenai, a language isolate of southeastern British Columbia and adjacent areas of Idaho and Montana, and to compare it to the obviation system of Algonquian languages. -

Researching and Reviving the Unami Language of the Lenape

Endangered Languages, Linguistics, and Culture: Researching and Reviving the Unami Language of the Lenape By Maureen Hoffmann A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Anthropology and Linguistics Bryn Mawr College May 2009 Table of Contents Abstract........................................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgments........................................................................................................... 4 List of Figures................................................................................................................. 5 I. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 6 II. The Lenape People and Their Languages .................................................................. 9 III. Language Endangerment and Language Loss ........................................................ 12 a. What is language endangerment?.......................................................................... 12 b. How does a language become endangered?.......................................................... 14 c. What can save a language from dying?................................................................. 17 d. The impact of language loss on culture ................................................................ 20 e. The impact of language loss on academia............................................................. 21 IV. -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America. -

Aspectual Forms in Lutsotso

Languages Research Journal in Modern Languages and Literatures https://royalliteglobal.com/languages-and-literatures & Literatures Research Article Section: Literature, Languages and Criticism This article is published Aspectual forms in Lutsotso by Royallite Global, Kenya in the Research Journal in Modern Languages and Hellen Odera¹ & David Barasa² Literatures, Volume 2, Issue ¹-²Department of Languages and Literature Education, 2, 2021 Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology, Kenya Article Information Correspondence: [email protected] Submitted: 15th Jan 2021 Accepted: 30th Mar 2021 Published: 5th April 2021 Abstract This paper analyses the inflectional category of aspect in Additional information is Lutsotso, a dialect of the Oluluhya macro-language. Using available at the end of the descriptive approach, the paper establishes that there are article a number of inflectional morphemes affixed on the verb https://creativecommons. root to express, e.g. person, number, tense, aspect and org/licenses/by/4.0/ mood. Among these affixes, tense and aspect categories interact largely, hence, it is difficult to study one category To read the paper without referring to the other. While tense and aspect are online, please scan this profoundly connected in Lutsotso, this paper only identifies QR code and describes the inflectional form of aspect. Generally, aspect in Lutsotso relates to the grammatical viewpoints such as the perfective, imperfective and iterative forms. This includes the temporal properties of situations and the situation types as well. Aspect just like other grammatical categories such as tense, mood, person, agreement and number are important in understanding the grammar of Lutsotso. Keywords: aspect, Bantu, Lutsotso verb How to Cite: Public Interest Statement Odera, H., & Barasa, D. -

Languages of the World--Native America

REPOR TRESUMES ED 010 352 46 LANGUAGES OF THE WORLD-NATIVE AMERICA FASCICLE ONE. BY- VOEGELIN, C. F. VOEGELIN, FLORENCE N. INDIANA UNIV., BLOOMINGTON REPORT NUMBER NDEA-VI-63-5 PUB DATE JUN64 CONTRACT MC-SAE-9486 EDRS PRICENF-$0.27 HC-C6.20 155P. ANTHROPOLOGICAL LINGUISTICS, 6(6)/1-149, JUNE 1964 DESCRIPTORS- *AMERICAN INDIAN LANGUAGES, *LANGUAGES, BLOOMINGTON, INDIANA, ARCHIVES OF LANGUAGES OF THE WORLD THE NATIVE LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS OF THE NEW WORLD"ARE DISCUSSED.PROVIDED ARE COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS AND DESCRIPTIONS OF THE LANGUAGES OF AMERICAN INDIANSNORTH OF MEXICO ANDOF THOSE ABORIGINAL TO LATIN AMERICA..(THIS REPOR4 IS PART OF A SEkIES, ED 010 350 TO ED 010 367.)(JK) $. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH,EDUCATION nib Office ofEduc.442n MD WELNicitt weenment Lasbeenreproduced a l l e a l O exactly r o n o odianeting es receivromed f the Sabi donot rfrocestarity it. Pondsof viewor position raimentofficial opinions or pritcy. Offkce ofEducation rithrppologicalLinguistics Volume 6 Number 6 ,Tune 1964 LANGUAGES OF TEM'WORLD: NATIVE AMER/CAFASCICLEN. A Publication of this ARC IVES OF LANGUAGESor 111-E w oRLD Anthropology Doparignont Indiana, University ANTHROPOLOGICAL LINGUISTICS is designed primarily, butnot exclusively, for the immediate publication of data-oriented papers for which attestation is available in the form oftape recordings on deposit in the Archives of Languages of the World. This does not imply that contributors will bere- stricted to scholars working in the Archives at Indiana University; in fact,one motivation for the publication -

Algonquian Connections to Salishan and Northeastern Archaeology

Algonquian Connections to Salishan and Northeastern Archaeology J. PETER DENNY University of Western Ontario Beyond the written records of the last few centuries, our access to Al gonquian history is through historical linguistics and archaeology. In this paper1 I discuss two problems in this regard: 1) the likelihood that Al gonquian languages and Salishan languages are genetically related, and 2) possible relations between Algonquian speech and the archaeological tradi tions of the Northeast. Since I am a semanticist, not a historical linguist or an archaeologist, my perspective centers on word meanings and upon selected lexical systems, notably noun classifiers and incorporated nouns It was semantic problems that first made me wonder about the complex ities of Algonquian history. I encountered a number of morphemes whose meanings seemed improbable if it were true that Algonquian speakers had always lived m small hunting bands like those of the Cree-Montagnais and Ojibwa speakers in the boreal forest. Some of the puzzles are these: 1) Proto-Algonquian (PA) *elenyiwa 'person' may come from the root *elen- ordinary ; this suggests the possibility that ordinary people were contrasted with higher status people in a stratified society at some time earlier in Al gonquian history. 2) WTDS.? SCTh°/ SPedal V6rb n^ ^°r aCti°nS d0ne * i»taun*»t. (not in oairsnt f • "f- ^^ WdI malked morPh°logically since they come cLTmarker w £T ^T verbs-hich always has a semantic verb th d ( enn y 985 d one SSil! f* t T ? L ? )' ™ for transitive inanimate verbs belonging to sub-class 1, which, under the analysis of Pigeott (1979^ if oT l983) haV Stem endi"S in a verb d« m-ker a^ ii See and Ojibwa this very clear-cut group contains an unexpected member I iK °<*-^ my study integrative articles concerned with geo.ranhlfre^n § VK 'T^ °Ut t0 be Peri ds since it is only at this level of inference^ thataXP. -

Download Download

The Southern Algonquians and Their Neighbours DAVID H. PENTLAND University of Manitoba INTRODUCTION At least fifty named Indian groups are known to have lived in the area south of the Mason-Dixon line and north of the Creek and the other Muskogean tribes. The exact number and the specific names vary from one source to another, but all agree that there were many different tribes in Maryland, Virginia and the Carolinas during the colonial period. Most also agree that these fifty or more tribes all spoke languages that can be assigned to just three language families: Algonquian, Iroquoian, and Siouan. In the case of a few favoured groups there is little room for debate. It is certain that the Powhatan spoke an Algonquian language, that the Tuscarora and Cherokee are Iroquoians, and that the Catawba speak a Siouan language. In other cases the linguistic material cannot be positively linked to one particular political group. There are several vocabularies of an Algonquian language that are labelled Nanticoke, but Ives Goddard (1978:73) has pointed out that Murray collected his "Nanticoke" vocabulary at the Choptank village on the Eastern Shore, and Heckeweld- er's vocabularies were collected from refugees living in Ontario. Should the language be called Nanticoke, Choptank, or something else? And if it is Nanticoke, did the Choptank speak the same language, a different dialect, a different Algonquian language, or some completely unrelated language? The basic problem, of course, is the lack of reliable linguistic data from most of this region. But there are additional complications. It is known that some Indians were bilingual or multilingual (cf. -

The Yurok Language Project at Berkeley: an Online Dictionary with Texts and Pedagogical Tools

The Yurok Language Project at Berkeley: An online dictionary with texts and pedagogical tools Andrew Garrett University of California, Berkeley In this paper, I report on an online dictionary project for a highly endangered Native language of North America. This project involves a dynamic lexicon, linked to a corpus of texts and enriched with several associated tools, which is designed to be useful for (and is regularly used by) scholars, language teachers, and language learners. The interest of this project for a broader audience emerges not from lexicographic innovations as such, but from how texts and lexicon are combined and how the interests of diverse user communities are addressed. 1. Background 1.1. Language context Yurok is spoken in northwestern California, near the Oregon border; it is one of three distantly related branches of the Algic language family. One of the other two branches also consists of a single language, Wiyot, formerly spoken just to the south along the Pacific coast; Teeter (1964) presents an overview (the last first-language speaker died in the 1960s). The third Algic branch comprises the widely dispersed Algonquian language family of central and eastern North America; for a brief survey see Mithun (1999: 327-340). Like most indigenous languages of California, Yurok was spoken in pre-contact times by relatively few people in a small territory; there were about 2,500 Yurok people occupying 80 miles along the lower Klamath River and the Pacific coast (Kroeber 1925: 17). In 2011 there are still a few elderly first-language speakers of Yurok, but it is no longer easy for them to play an active role in language teaching. -

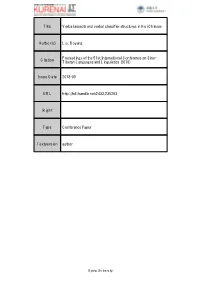

Title Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese

Title Verbal aspects and verbal classifier structures in Hui Chinese Author(s) Liu, Boyang Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino- Citation Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018) Issue Date 2018-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235293 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion author Kyoto University Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese LIU Boyang (EHESS-CRLAO) CONTENT • PART I: Research Purpose • PART II: The definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 1. An introduction to Hui Chinese – 2. Previous work on VCLs in Mandarin – 3. A provisional definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 4. Lexical aspects indicated by the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP] in Sinitic languages – 5. Relationships between grammatical aspects and the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP- OBJECT] • PART III: Grammatical aspects indicated by special auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures in Hui Chinese – 6. The perfective aspect – 7. The imperfective aspect • PART IV: Conclusion PART I: RESEARCH PURPOSE Research Purpose: • Verbal classifiers (VCLs) have been much less studied from a typological perspective than the category of nominal classifiers (NCLs), and even less in the non-Mandarin branches of Sinitic languages, such as the Hui dialects; • In this study, I will introduce relationships between lexical aspects, grammatical aspects and verbal classifier phrases (VCLPs) in Hui Chinese, analyzing the similarities and differences with Standard Mandarin. • Verbal classifier structures in the Hui dialects display a transitional feature compared with Xiang, Gan and Wu, taking auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures as examples (auto-VCLs derive from verb reduplicants in the verb phrase [VERB- (‘one’)-VERB]): – Auto-VCLs in the verb phrase [VERB-AUTO VCL] can code the perfective or imperfective aspect in different types of complex sentences in Hui Chinese; – More variety of auto-VCL structures is found in Hui Chinese compared with Xiang and Gan dialects. -

FY2015 Outcome Evaluations of ANA Projects Report

FY 2015 Outcome Evaluations of Administration for Native Americans Projects Report to Congress FY 2015 Annual Report to Congress Outcome Evaluations of Administration for Native Americans Projects TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ 4 2015 Key Findings ............................................................................................................................. 7 ANA SEDS Economic Development .............................................................................................. 11 ANA SEDS Social Development .................................................................................................... 12 ANA Environmental Regulatory Enhancement .............................................................................. 13 ANA Native Languages ................................................................................................................... 14 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................ 16 Aleut Community of St. Paul Island ................................................................................................. 17 Chugachmiut ..................................................................................................................................... 19 Cook Inlet Tribal Council, Inc. ........................................................................................................