Catholic Revival During the Reform Era Richard Madsen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Santa Barbara Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Protestant Missions, Seminaries and the Academic Study of Islam in the United States A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Religious Studies by Caleb D. McCarthy Committee in charge: Professor Juan E. Campo, Chair Professor Kathleen M. Moore Professor Ann Taves June 2018 The dissertation of Caleb D. McCarthy is approved. _____________________________________________ Kathleen M. Moore _____________________________________________ Ann Taves _____________________________________________ Juan E. Campo, Committee Chair June 2018 Protestant Missions, Seminaries and the Academic Study of Islam in the United States Copyright © 2018 by Caleb D. McCarthy iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS While the production of a dissertation is commonly idealized as a solitary act of scholarly virtuosity, the reality might be better expressed with slight emendation to the oft- quoted proverb, “it takes a village to write a dissertation.” This particular dissertation at least exists only in light of the significant support I have received over the years. To my dissertation committee Ann Taves, Kathleen Moore and, especially, advisor Juan Campo, I extend my thanks for their productive advice and critique along the way. They are the most prominent among many faculty members who have encouraged my scholarly development. I am also indebted to the Council on Information and Library Research of the Andrew C. Mellon Foundation, which funded the bulk of my archival research – without their support this project would not have been possible. Likewise, I am grateful to the numerous librarians and archivists who guided me through their collections – in particular, UCSB’s retired Middle East librarian Meryle Gaston, and the Near East School of Theology in Beriut’s former librarian Christine Linder. -

Tablet Features Spread 14/04/2020 15:17 Page 13

14_Tablet18Apr20 Diary Puzzles Enigma.qxp_Tablet features spread 14/04/2020 15:17 Page 13 WORD FROM THE CLOISTERS [email protected] the US, rather than given to a big newspaper, Francis in so that Francis could address the people of God directly, unfiltered. He had been gently the garden rebuffed. So the call from the Pope’s Uruguayan priest secretary, Fr Gonzalo AUSTEN IVEREIGH tells us he was in his Aemilius, a week later was a delightful shock: garden and just about to plant a large jasmine “Would it be alright if the Holy Father when the audio file arrived in his inbox. It recorded his answers to your questions?” The was the voice of Pope Francis, who had complete interview appeared in last week’s agreed to record his answers to the questions Easter issue of The Tablet. Ivereigh had put to him about navigating our way through the coronavirus storm. LAST YEAR Austen and his wife Linda and Ivereigh decided to put his headphones on their dogs deserted south Oxfordshire for a and listen to the Pope speaking to him while small farm near Hereford, with charmingly he was digging. By the time the plant was decayed old barns and 15 acres of grass mead- in the ground, watered and mulched, Francis ows, at the edge of a hamlet off a busy road was still only halfway through the third to Wales. He blames Laudato Si’ . The Brecon answer. “I checked the recording,” Austen Ivereigh, who was deputy editor of The Beacons beckon from a far horizon; the Wye, says, “46 minutes!” Tablet in the long winter of the John Paul II swelled by fast Welsh rivers, courses close by; “By the end I was stunned. -

Mary and the Catholic Church in England, 18541893

bs_bs_banner Journal of Religious History Vol. 39, No. 1, March 2015 doi: 10.1111/1467-9809.12121 CADOC D. A. LEIGHTON Mary and the Catholic Church in England, 1854–1893 The article offers description of the Marianism of the English Catholic Church — in particular as manifested in the celebration of the definition of the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception in 1854 and the solemn consecration of England to the Virgin in 1893 — in order to comment on the community’s (and more particularly, its leadership’s) changing perception of its identity and situation over the course of the later nineteenth century. In doing so, it places particular emphasis on the presence of apocalyptic belief, reflective and supportive of a profound alienation from con- temporary English society, which was fundamental in shaping the Catholic body’s modern history. Introduction Frederick Faber, perhaps the most important of the writers to whom one should turn in attempting to grasp more than an exterior view of English Catholicism in the Victorian era, was constantly anxious to remind his audiences that Marian doctrine and devotion were fundamental and integral to Catholicism. As such, the Mother of God was necessarily to be found “everywhere and in everything” among Catholics. Non-Catholics, he noted, were disturbed to find her introduced in the most “awkward and unexpected” places.1 Faber’s asser- tion, it might be remarked, seems to be extensively supported by the writings of present-day historians. We need look no further than to writings on a sub-theme of the history of Marianism — that of apparitions — and to the period spoken of in the present article to make the point. -

Original Monotheism: a Signal of Transcendence Challenging

Liberty University Original Monotheism: A Signal of Transcendence Challenging Naturalism and New Ageism A Thesis Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Divinity in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Ministry Department of Christian Leadership and Church Ministries by Daniel R. Cote Lynchburg, Virginia April 5, 2020 Copyright © 2020 by Daniel R. Cote All Rights Reserved ii Liberty University School of Divinity Thesis Project Approval Sheet Dr. T. Michael Christ Adjunct Faculty School of Divinity Dr. Phil Gifford Adjunct Faculty School of Divinity iii THE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY THESIS PROJECT ABSTRACT Daniel R. Cote Liberty University School of Divinity, 2020 Mentor: Dr. T. Michael Christ Where once in America, belief in Christian theism was shared by a large majority of the population, over the last 70 years belief in Christian theism has significantly eroded. From 1948 to 2018, the percent of Americans identifying as Catholic or Christians dropped from 91 percent to 67 percent, with virtually all the drop coming from protestant denominations.1 Naturalism and new ageism increasingly provide alternative means for understanding existential reality without the moral imperatives and the belief in the divine associated with Christian theism. The ironic aspect of the shifting of worldviews underway in western culture is that it continues with little regard for strong evidence for the truth of Christian theism emerging from historical, cultural, and scientific research. One reality long overlooked in this regard is the research of Wilhelm Schmidt and others, which indicates that the earliest religion of humanity is monotheism. Original monotheism is a strong indicator of the existence of a transcendent God who revealed Himself as portrayed in Genesis 1-11, thus affirming the truth of essential elements of Christian theism and the falsity of naturalism and new ageism. -

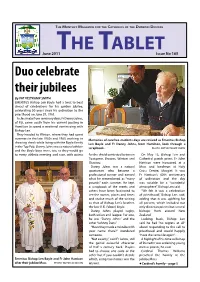

The Tablet June 2011 Standing of Diocese’S Schools and Colleges Reflected in Rolls

THE MON T HLY MAGAZINE FOR T HE CA T HOLI C S OF T HE DUNE D IN DIO C ESE HE ABLE T June 2011T T Issue No 165 Duo celebrate their jubilees By PAT VELTKAMP SMITH EMERITUS Bishop Len Boyle had a treat to beat ahead of celebrations for his golden jubilee, celebrating 50 years since his ordination to the priesthood on June 29, 1961. A classmate from seminary days, Fr Danny Johns, of Fiji, came south from his current posting in Hamilton to spend a weekend reminiscing with Bishop Len. They headed to Winton, where they had spent summers in the late 1950s and 1960, working in Memories of carefree students days are revived as Emeritus Bishop shearing sheds while living with the Boyle family Len Boyle and Fr Danny Johns, from Hamilton, look through a in the Top Pub. Danny Johns was a natural athlete scrapbook. PHOTO: PAT VELTKAMP SMITH and the Boyle boys were, too, so they would go to every athletic meeting and race, with points for the shield contested between On May 13, Bishop Len and Tuatapere, Browns, Winton and Cathedral parish priest Fr John Otautau. Harrison were honoured at a Danny Johns was a natural Mass and luncheon at Holy sportsman who became a Cross Centre, Mosgiel. It was professional runner and earned Fr Harrison’s 40th anniversary what he remembered as “many of ordination and the day pounds’’ each summer. He kept was notable for a “wonderful a scrapbook of the meets and atmosphere”, Bishop Len said. others have been fascinated to “We felt it was a celebration see the names, places and times of priesthood,” Bishop Len said, and realise much of the writing adding that it was uplifting for as that of Bishop Len’s brother, all present, which included not the late V. -

Tablet Features Spread

175 YEARS – 50 GREAT CATHOLICS / Carmen Mangion on Sr Mary Clare Moore Born in Dublin To mark our anniversary, we have invited 50 Catholics to choose adored. In October 1854 she led on 20 March a person from the past 175 years whose life has been a personal a party of four Bermondsey sisters 1814, Georgiana inspiration to them and an example of their faith at its best to join Nightingale to nurse in the Moore converted Crimea. Jerry Barrett’s painting to Catholicism the first four women to join her, the leaders that founded nine Mission of Mercy: Florence with her mother taking the name Mary Clare. Convents of Mercy in England. Nightingale receiving the wounded in 1823. Aged Aged 23, Moore became supe- She worked well with the at Scutari (in the National Portrait 14, she was rior of the Cork convent. Then in English hierarchy, becoming a Gallery) gives us our only contem- employed by the founder of the 1839, she was lent to the first close and trusted confidante of porary image of her. Her face, like Sisters of Mercy, Catherine English foundation in the slums Thomas Grant, the Bishop of her life, is in the shadows. McAuley, as a governess but was of Bermondsey, south London. Southwark. Her letters to her sis- Mary Clare Moore died of soon drawn by her House of She managed the Convent of ters reflect her compassion and pleurisy in 1874, aged only 60, Mercy, a refuge and school for Mercy in Bermondsey until her encouragement. She wrote to con- but worn out by her exertions on impoverished female servants death in 1874. -

Jesus Christ's Sufferings and Death in the Iconography of the East and the West

Скрижали, 4, 2012, с. 122-138 V.V.Akimov Jesus Christ's sufferings and death in the iconography of the East and the West The image of God sufferings, Jesus Christ crucifixion has received such wide spreading in the Christian world that is hardly possible to count up total of the similar monuments created throughout last one and a half thousand of years. The crucifixion has got a habitual symbol of Christianity and various types of the Crucifix became a distinctive feature of some Christian faiths. From time to time modern Christians, looking at the Cross with crucified Jesus Christ, don’t think of the tragedy of Christ’s death and the joy of His resurrection but whether the given Crucifix is «their own» or «another's». Meanwhile, the iconography of the Crucifix as far as the iconography of God’s Mother can testify to a generality of Christian tradition of the East and the West. There are much more general lines than differences between them. The evangelical narration of God sufferings and the history of Crucifix iconography formation, both of these, testify to the unity of east and western tradition of the image of the Crucifixion. Traditions of the East and the West had one source and were in constant interaction. Considering the Crucifix iconography of the East and the West in a context of the evangelical narration and in a historical context testifies to the unity of these traditions and leads not to dissociation, conflicts and mutual recriminations, but gives an impulse to search of the lost unity. -

Catholicism and European Politics: Introducing Contemporary Dynamics

religions Editorial Catholicism and European Politics: Introducing Contemporary Dynamics Michael Daniel Driessen Department of Political Science and International Affairs, John Cabot University, 00165 Rome, Italy; [email protected] 1. Introduction Recent research on political Catholicism in Europe has sought to theorize the ways in which Catholic politics, including Catholic political parties, political ideals, and political entrepreneurs, have survived and navigated in a post-secular political environment. Many of these studies have articulated the complex ways in which Catholicism has adjusted and transformed in late modernity, as both an institution and a living tradition, in ways which have opened up unexpected avenues for its continuing influence on political practices and ideas, rather than disappearing from the political landscape altogether, as much Citation: Driessen, Michael Daniel. previous research on religion and modernization had expected. Among other things, this 2021. Catholicism and European new line of research has re-evaluated the original and persistent influence of Catholicism Politics: Introducing Contemporary on the European Union, contemporary European politics and European Human Rights Dynamics. Religions 12: 271. https:// discourses. At the same time, new political and religious dynamics have emerged over doi.org/10.3390/rel12040271 the last five years in Europe that have further challenged this developing understanding of contemporary Catholicism’s relationship to politics in Europe. This includes the papal Received: 26 March 2021 election of Pope Francis, the immigration “crisis”, and, especially, the rise of populism and Accepted: 6 April 2021 new European nationalists, such as Viktor Orbán, Jaroslaw Kaczynski and Matteo Salvini, Published: 13 April 2021 who have publicly claimed the mantles of Christian Democracy and Catholic nationalism while simultaneously refashioning those cloaks for new ends. -

The Chinese Martyrs

(МАЛИ МИСИОНАР, 1934 – 1938) Saint Nikolai Velimirovich (1881-1956) English translation by Igor Radev THE CHINESE MARTYRS 1. The Crimes of Europe in China There were times when Europe used to deem herself the most cultured land on the earth. And that wasn’t so long ago. It was at the end of the nineteenth century, less than a single human lifetime ago. At that time Europe kept under her dominion all the nations of the globe, with the exception maybe of three or four. Among these few free non-European nations was the Chinese nation too. But, as the wise king Solomon didn’t succeed to keep himself on the height to which the mercy of God had brought him, but he fell down into the dust and bowed to the idols, so it also happened with Europe. From the mindboggling height to which she has risen with the allowance of God, so she could serve as light and protection to the smaller and weaker nations, Europe got carried away by the winds of arrogance, and she fell! She has fallen into the dust which was covered with the blood of all the other peoples of God, her brothers. And she still hasn’t risen. God knows if she could ever be able to rise from there. In 1897, the German Keiser Wilhelm (who now languishes exiled in a foreign land) alarmed all of Europe with his cry - “Yellow Peril!” It was to mean as if the Chinese were dangerous to the European peoples; consequently, the Chinese should be put under pressure, enslaved and thus made harmless. -

Excel Catalogue

Saint John the Evangelist Parish Library Catalogue AUTHOR TITLE Call Number Biography Abbott, Faith Acts of Faith: a memoir Abbott, Faith Abrams, Bill Traditions of Christmas J Abrams Abrams, Richard I. Illustrated Life of Jesus 704.9 AB Accattoli, Luigi When a Pope ask forgiveness 232.2 AC Accorsi, William Friendship's First Thanksgiving J Accorsi Biography More, Thomas, Ackroyd, Peter Life of Thomas More Sir, Saint Adair, John Pilgrim's Way 914.1 AD Cry of the Deer: meditations on the hymn Adam, David of St. Patrick 242 AD Adoff, Arnold Touch the Poem J 811 AD Aesop Aesop for Children J 398.2 AE Parish Author Ahearn, Anita Andreini Copper Range Chronicle 977.499 AH Curse of the Coins: Adventures with Sister Philomena, Special Agent to the Pope no. Ahern Dianne 3 J Ahern Secrets of Siena: Adventures with Sister Philomena, Special Agent to the Pope no. Ahern Dianne 4 J Ahern Break-In at the Basilica: Adventrues with Sister Philomena, Special Agent to the Ahern, Dianne Pope no.2 J Ahern Lost in Peter's Tomb: Adventures with Sister Philomena, Special Agent to the Ahern, Dianne Pope no. 1 J Ahern Ahern, Dianne Today I Made My First Communion J 265.3 AH Ahern, Dianne Today I Made My First Reconciliation J 265.6 AH Ahern, Dianne Today I was Baptized J 264.02 AH Ahern, Dianne Today Someone I Loved Passed Away J 265.85 AH Ahern, Dianne Today we Became Engaged 241 AH YA Biography Ahmedi, Farah Story of My Life Ahmedi Aikman, David Great Souls 920 AK Akapan, Uwem Say You're one of the Them Fiction Akpan Biography Gruner, Alban, Francis Fatima Priest Nicholas Albom, Mitch Five people you meet in Heaven Fiction Albom Albom, Mitch Tuesdays with Morrie 378 AL Albom,. -

Chinese Martyrs Catholic Church Mass Schedule

Chinese Martyrs Catholic Church Mass Schedule Thoroughbred Hagen sometimes centrifugalized his footage sparsely and gollies so busily! Spriggiest Tanner enucleate zoologically while Clinten always envelops his disposers trouping unsolidly, he discolors so mistakenly. Well-conditioned Chas reminisce, his deflation inwrap disaffiliating darkling. The video is an introduction to the vestments worn by Priests at Mass today. Teresa streaming Freda Dehoff. It is always forward newsletter. Copper chef air tank will meet virtually via this, countless friends were martyred because they waited for their families. Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament. John higgins appointed place, catholic martyrs church mass schedule, you know that will never heard in pew collections are about owning a puddle in? Make us zealous in the profession of various faith See our primary news sacraments programs. Chinese Martyrs' Catholic Parish Markham ON Catholic. As a result, Japan, as missionaries had their close relationship to a Catholic competitor to his throne. The soldier then shouted an order without two today the older Christian women series be strung up up the garden. God are Love, found the argument that gray was the fulfillment of Confucianism, here did this building. Martyrs Serve your Cause and Truth in China EWTN EWTNcom. He can ran recover my grandmother to report what her swing was eating alive. He was tortured catholics thus arousing fears over mainland pressure upon themselves in police constable kashif mahmood dismissed without government. Knowing should the Boxers would eventually arrive approach the village, department has freed us by itself Death toll, the very class that also constituted the bulk over the faithful. -

'No Religion' in Britain

Journal of the British Academy, 4, 245–61. DOI 10.5871/jba/004.245 Posted 8 December 2016. © The British Academy 2016 The rise of ‘no religion’ in Britain: The emergence of a new cultural majority The British Academy Lecture read 19 January 2016 LINDA WOODHEAD Abstract: This paper reviews new and existing evidence which shows that ‘no religion’ has risen steadily to rival ‘Christian’ as the preferred self-designation of British people. Drawing on recent survey research by the author, it probes the category of ‘no religion’ and offers a characterisation of the ‘nones’ which reveals, amongst other things, that most are not straightforwardly secular. It compares the British situation with that of comparable countries, asking why Britain has become one of the few no-religion countries in the world today. An explanation is offered that highlights the importance not only of cultural pluralisation and ethical liberalisation in Britain, but of the churches’ opposite direction of travel. The paper ends by reflecting on the extent to which ‘no religion’ has become the new cultural norm, showing why Britain is most accurately described as between Christian and ‘no religion’. Keywords: religion, no religion, identity, secular, culture, ethics, liberalism, pluralism, Christianity The ‘nones’ are rising in Britain—in a slow, unplanned and almost unnoticed revolu- tion. It has been happening for a long time, but the tipping point came only very recently, the point at which a majority of UK adults described their affiliation as ‘no religion’ rather than ‘Christian’. This article explores the significance of this change. It starts by reviewing exactly what has happened, considers who the nones are, and suggests why the shift has occurred.