Urban Renaissance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Urban Entrepreneurialism to a “Revanchist City”? on the Spatial Injustices of Glasgow’S Renaissance

From Urban Entrepreneurialism to a “Revanchist City”? On the Spatial Injustices of Glasgow’s Renaissance Gordon MacLeod Department of Geography, University of Durham, Durham, UK; [email protected] Recent perspectives on the American city have highlighted the extent to which the economic and sociospatial contradictions generated by two decades of “actually exist- ing” neoliberal urbanism appear to demand an increasingly punitive or “revanchist” political response. At the same time, it is increasingly being acknowledged that, after embracing much of the entrepreneurial ethos, European cities are also confronting sharpening inequalities and entrenched social exclusion. Drawing on evidence from Glasgow, the paper assesses the dialectical relations between urban entrepreneurial- ism, its escalating contradictions, and the growing compulsion to meet these with a selective appropriation of the revanchist political repertoire. Introduction Spurred on by the unrelenting pace of globalization and the entrenched political hegemony of a neoliberal ideology, throughout the last two decades a host of urban governments in North America and Western Europe have sought to recapitalize the economic land- scapes of their cities. While these “entrepreneurial” strategies might have refueled the profitability of many city spaces across the two con- tinents, the price of such speculative endeavor has been a sharpening of socioeconomic inequalities alongside the institutional displacement and “social exclusion” of certain marginalized groups. One political response to these social geographies of “actually existing neoliberalism” (Brenner and Theodore [paper] this volume) sees the continuous renaissance of the entrepreneurial city being tightly “disciplined” through a range of architectural forms and institutional practices so that the enhancement of a city’s image is not compromised by the visible presence of those very marginalized groups. -

The City of Edinburgh Council

Notice of meeting and agenda The City of Edinburgh Council 10.00 am, Thursday, 15 December 2016 Council Chamber, City Chambers, High Street, Edinburgh This is a public meeting and members of the public are welcome to attend Contact E-mail: [email protected] Tel: 0131 529 4246 1. Order of business 1.1 Including any notices of motion and any other items of business submitted as urgent for consideration at the meeting. 2. Declaration of interests 2.1 Members should declare any financial and non-financial interests they have in the items of business for consideration, identifying the relevant agenda item and the nature of their interest. 3. Deputations 3.1 If any 4. Minutes 4.1 The City of Edinburgh Council of 24 November 2016 (circulated) – submitted for approval as a correct record 5. Questions 5.1 By Councillor Bagshaw - Key Junctions on Princes Street – for answer by the Convener of the Transport and Environment Committee 5.2 By Councillor Booth – Council Support for Small and Medium Sized Shops – for answer by the Convener of the Economy Committee 5.3 By Councillor Booth – Forth Ports - for answer by the Convener of the Economy Committee 5.4 By Councillor Booth – Low Emission or Clean Air Zones - for answer by the Convener of the Transport and Environment Committee 5.5 By Councillor Booth – Air Quality Management Area - for answer by the Convener of the Transport and Environment Committee 5.6 By Councillor Burgess – Long Term Empty Homes – for answer by the Convener of the Health, Social Care and Housing Committee 5.7 By -

Influences of Gentrification on Identity Shift of an Urban Fragment - a Case Study

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Directory of Open Access Journals SPATIUM International Review UDK 711.433(497.113) ; 316.334.56 ; 72.01 No. 21, December 2009, p. 66-75 Original scientific paper INFLUENCES OF GENTRIFICATION ON IDENTITY SHIFT OF AN URBAN FRAGMENT - A CASE STUDY Dejana Nedučin1, University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Technical Sciences, Department of Architecture and Urban Planning, Novi Sad, Serbia Olga Carić, University Business Academy, Faculty of Economics and Engineering Management, Novi Sad, Serbia Vladimir Kubet, University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Technical Sciences, Department of Architecture and Urban Planning, Novi Sad, Serbia This paper discusses the process of gentrification, researched through a perspective of its positive and negative aspects. It underlines the importance of reasonable proportioning, sensible structuring and long-term planning of transformation of urban spaces, which contributes to an upgrade of living conditions and qualitative advancement of social consciousness and development of needs of the local inhabitants, regardless of their socio-economic profile. Despite not perceiving gentrification as an a priori negative process, influences of alterations of urban tissue carried out through radical and narrowly interpreted modifications of their character may cause undesired changes in the perception and use of the space and were analyzed as well. A case study of the gentrification of Grbavica, an urban fragment in Novi Sad, Serbia, is presented. The goal of this -

Housing Regeneration in Glasgow: Gentrification and Upward Neighbourhood Trajectories in a Post-Industrial City

eSharp Issue 7 Faith, Belief and Community Housing regeneration in Glasgow: Gentrification and upward neighbourhood trajectories in a post-industrial city. Zhan McIntyre (University of Glasgow) Introduction There is growing concern among governments in the developed world about the future of cities (Schoon, 2001).1 Arguably, this concern has had particular prominence for the ‘urban dinosaurs’, that is the de-industrialising or ‘rust belt cities’ that at one time depended upon heavy manufacturing as the main source of employment. The contraction of manufacturing employment in the older industrial cities in Europe since the 1960s onwards created specific challenges for these cities including massive unemployment, a growth in poverty, the physical and social degeneration of the urban fabric and significant population loss. Despite public investment and policy measures implemented by different scales of government, these problems have persisted (Bailey et al., 1999). Therefore, an international trend of urban renewal is a focus on housing-led regeneration strategies. It is noted by some commentators that the endorsement of housing rehabilitation, neighbourhood renewal and urban renaissance is a ‘mantle under which gentrification is being promoted’ (Atkinson, 2004, p.107; Lees, 2000). Simply put, gentrification is a re-occurring process in areas undergoing urban renewal projects. However, this is problematic in two respects. The first relates to the contested views regarding the goals of public policy. The second concerns the process of gentrification itself, specifically as it has been seen as a regressive and negative process within the academic community because of the displacement it tends to cause for the poorest and most vulnerable members of the community, and its portrayal as the physical expression of a more sinister and aggressive neoliberal ‘revanchist’ policy discourse (Smith, 1996; MacLeod, 2002; Atkinson, 2003; Harvey, 2003). -

Urban Strategy Or Urban Solution?: Visions of a Gentrified Waterfront in Rotterdam and Glasgow Brian Doucet U

Urban strategy or urban solution?: Visions of a gentrified waterfront in Rotterdam and Glasgow Brian Doucet Utrecht University Conference Paper Association of American Geographers 2013 PortcityScapes Special Session Friday 12 April 2013 This is a draft paper. Please do not cite without consultation with the author Abstract The transformation of old inner‐city harbour areas into mixed‐use, high‐end flagship developments is one of the biggest processes of urban change impacting port cities. These spaces are part of the gentrified urban landscape, which, as recent scholarship has demonstrated, is largely state‐ or municipally‐led. Our currently knowledge on the goals of gentrification focuses on three objectives: urban entrepreneurial policies of growth and place promotion, creating liveable cities and neighbourhoods and ‘revanchist’ attitudes towards poor and marginalised groups. However, we lack a deep understanding of the visions and ideas of key initiators of municipally‐led gentrification; these first‐hand accounts tend to get ignored when examining gentrification as an urban strategy more broadly. Therefore, the aim of this article is to gain more insight into these visions which drive municipal leaders to promote gentrified spaces along their urban waterfronts. It will examine the specific cases of high‐end, mixed‐use developments in Rotterdam and Glasgow. Both waterfronts were championed by individual leaders whose visions led to the transformation of their respective waterfronts from industrial or abandoned places to post‐industrial, consumption‐oriented spaces. A detailed analysis of these visions reveals that they are clearly rooted in addressing key social and economic problems of their cities: in Rotterdam this is centred on the divisions between the northern and southern halves of the city; in Glasgow, it is focused on employment opportunities. -

New-Build `Gentrification' and London's Riverside Renaissance

Environment and Planning A 2005, volume 37, pages 1165 ^ 1190 DOI:10.1068/a3739 New-build `gentrification' and London's riverside renaissance Mark Davidson, Loretta Lees Department of Geography, King's College London, Strand, London WC2R 2LS, England; e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Received 3 February 2004; in revised form 5 August 2004 Abstract. In a recent conference paper Lambert and Boddy (2002) questioned whether new-build residential developments in UK city centres were examples of gentrification. They concluded that this stretched the term too far and coined `residentialisation' as an alternative term. In contrast, we argue in this paper that new-build residential developments in city centres are examples of gentrification. We argue that new-build gentrification is part and parcel of the maturation and mutation of the gentrification process during the post-recession era. We outline the conceptual cases for and against new-build `gentrification', then, using the case of London's riverside renaissance, we find in favour of the case for. ``In the last decade the designer apartment blocks built by corporate developers for elite consumption have become as characteristic of gentrified landscapes as streetscapes of lovingly restored Victorian terraces. As gentrification continues to progress and exhibit new forms and patterns, it seems unnecessary to confine the concept to residential rehabilitation.'' Shaw (2002, page 44) 1 Introduction Recent gentrification research has begun to highlight the challenges that current waves of gentrification pose towards its conceptualisation (Lees, 2003a; Slater, 2004). In the last decade gentrification has matured and its processes are operating in a new economic, cultural, social, and political environment. -

Gendered Residential Space

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences April 2008 Gendered Residential Space KeAndra D. Dodds University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Recommended Citation Dodds, KeAndra D., "Gendered Residential Space" 22 April 2008. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/80. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/80 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gendered Residential Space Abstract Gay Villages, Gay Ghettos, and other gay and lesbian residential enclaves have all become a standard part of urban space, but who actually lives in these neighborhoods and how does each differ? One obvious variation is gender, particularly as it is traditionally understood. As a population that inherently breaks conventional gender stereotypes, is it possible that gay and lesbian settlement patterns still reinforce gender stereotypes? This paper explores gender in neighborhoods with high lesbian and gay populations and particularly questions what are the factors that lead lesbians to concentrate in certain residential spaces. The research focuses on the Philadelphia neighborhoods of Mount Airy and Washington Square West and serves to better understand gendered space in the larger scheme of urban settlement. Keywords Urban settlement, Lesbian, Lesbians, Gayborhood, Gay Ghetto, Mount Airy, LGBT Neighborhoods, Gendered Space, Urban Space, Social Sciences, Urban Studies, Eric Schneider, Schneider, Eric This article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/80 Preface While my family moved too often to really get to know one, residential communities have always fascinated me. -

20 Years of Urban Policy At

OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities 20 years of urban policy at About CFE The OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities provides comparative statistics, analysis and capacity building for local and national actors to work together to unleash the potential of entrepreneurs and small and medium-sized enterprises, promote inclusive and sustainable regions and cities, boost local job creation, and support sound tourism policies. www.oecd.org/cfe/|@OECD_local © OECD 2019 This paper is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and the arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document, as well as any statistical data and map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS How does the OECD work on cities?.................................................................4 Key messages from OECD reports on cities………………………….………….11 Key facts on cities.....……………………………………………....……………… 12 OECD Impact Assessment Survey……………………………………………......17 Testimonies from Chairs of the OECD Working Party on Urban Policy……….22 Selected testimonies from OECD countries. …………………………………….26 This document was produced for the 20th anniversary of the OECD Regional Development Policy Committee and the OECD Working Party on Urban Policy. 3 How does -

Transforming Barcelona: the Renewal of a European Metropolis/Edited by Tim Marshall

Transforming Barcelona Barcelona is perhaps the European city that has become most renowned for successfully “remaking” itself in the last 20 years. This image has been spread cumulatively around the world by books, television and internet sites, as well as by films and the use of the city in advertisements. This book is about the reality behind that image. It describes how the governors, professional planners and architects, and, in a wider sense, the people of the city and of Catalonia brought about the succession of changes which began around 1980. Transforming Barcelona is made up of chapters by those involved in the changes and by local experts who have been observing the changes year by year. Particular emphasis is placed on the political leadership and on the role of professionals, especially architects, in catalysing and implementing urban change. Other chapters look closely at the way that the treatment of public space became a key ingredient of what has been termed the “Barcelona model”. Critiques of this model consider from two different perspectives — environmental and cultural — how far the generally acclaimed successes stand up to full analysis. The book is fully illustrated and contains an up-to-date bibliography of writings on the city in English. This book will be of particular interest to those studying or practising in the fields of urban regeneration, urban design and urban geography, as well as all those fascinated by the multiple dimensions of the current transformation of older cities. No other book is available in English that provides such extensive understanding of Barcelona from authoritative local participants and observers. -

Is Urban Decay Bad? Is Urban Revitalization Bad Too?

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES IS URBAN DECAY BAD? IS URBAN REVITALIZATION BAD TOO? Jacob L. Vigdor Working Paper 12955 http://www.nber.org/papers/w12955 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2007 The author is grateful to Yongsuk Lee, Joshua Kinsler and Patrick Dudley for research assistance, and to Erzo F.P. Luttmer and seminar participants at Yale University, the 2006 NBER Summer Institute workshop on Public Economics and Real Estate, and at the 2005 American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association International Meeting for helpful comments on earlier drafts. Remaining errors are the author's responsibility. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2007 by Jacob L. Vigdor. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Is Urban Decay Bad? Is Urban Revitalization Bad Too? Jacob L. Vigdor NBER Working Paper No. 12955 March 2007 JEL No. D1,R21,R31 ABSTRACT Many observers argue that urban revitalization harms the poor, primarily by raising rents. Others argue that urban decline harms the poor by reducing job opportunities, the quality of local public services, and other neighborhood amenities. While both decay and revitalization can have negative effects if moving costs are sufficiently high, in general the impact of neighborhood change on utility depends on the strength of price responses to neighborhood quality changes. Data from the American Housing Survey are used to estimate a discrete choice model identifying households' willingness-to-pay for neighborhood quality. -

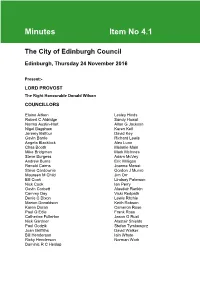

Minutes Item No 4.1

Minutes Item No 4.1 The City of Edinburgh Council Edinburgh, Thursday 24 November 2016 Present:- LORD PROVOST The Right Honourable Donald Wilson COUNCILLORS Elaine Aitken Lesley Hinds Robert C Aldridge Sandy Howat Norma Austin-Hart Allan G Jackson Nigel Bagshaw Karen Keil Jeremy Balfour David Key Gavin Barrie Richard Lewis Angela Blacklock Alex Lunn Chas Booth Melanie Main Mike Bridgman Mark McInnes Steve Burgess Adam McVey Andrew Burns Eric Milligan Ronald Cairns Joanna Mowat Steve Cardownie Gordon J Munro Maureen M Child Jim Orr Bill Cook Lindsay Paterson Nick Cook Ian Perry Gavin Corbett Alasdair Rankin Cammy Day Vicki Redpath Denis C Dixon Lewis Ritchie Marion Donaldson Keith Robson Karen Doran Cameron Rose Paul G Edie Frank Ross Catherine Fullerton Jason G Rust Nick Gardner Alastair Shields Paul Godzik Stefan Tymkewycz Joan Griffiths David Walker Bill Henderson Iain Whyte Ricky Henderson Norman Work Dominic R C Heslop 1. Queensferry High School a) Deputation by Kirkliston Community Council and Kirkliston Primary School PTA The deputation felt that the current school provision at Queensferry High was not fit for purpose. They expressed concerns that the feasibility study had not been thorough enough and that the projected increase in numbers of children who would attend the new school had been understated. The deputation stated that it was imperative that the new school should be in place by 2023. They asked the Council to note their concerns that the proposal for the new build was not included in the Second Local Development Plan, an actual site location for the proposed development had not been identified and there was no funding secured for the project. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part One ISBN 0 902 198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART I A-J C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography.