Acid-Base Strength Chapter 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is There an Acid Strong Enough to Dissolve Glass? – Superacids

ARTICLE Is there an acid strong enough to dissolve glass? – Superacids For anybody who watched cartoons growing up, the word unit is based on how acids behave in water, however as acid probably springs to mind images of gaping holes being very strong acids react extremely violently in water this burnt into the floor by a spill, and liquid that would dissolve scale cannot be used for the pure ‘common’ acids (nitric, anything you drop into it. The reality of the acids you hydrochloric and sulphuric) or anything stronger than them. encounter in schools, and most undergrad university Instead, a different unit, the Hammett acidity function (H0), courses is somewhat underwhelming – sure they will react is often preferred when discussing superacids. with chemicals, but, if handled safely, where’s the drama? A superacid can be defined as any compound with an People don’t realise that these extraordinarily strong acids acidity greater than 100% pure sulphuric acid, which has a do exist, they’re just rarely seen outside of research labs Hammett acidity function (H0) of −12 [1]. Modern definitions due to their extreme potency. These acids are capable of define a superacid as a medium in which the chemical dissolving almost anything – wax, rocks, metals (even potential of protons is higher than it is in pure sulphuric acid platinum), and yes, even glass. [2]. Considering that pure sulphuric acid is highly corrosive, you can be certain that anything more acidic than that is What are Superacids? going to be powerful. What are superacids? Its all in the name – super acids are intensely strong acids. -

The Strongest Acid Christopher A

Chemistry in New Zealand October 2011 The Strongest Acid Christopher A. Reed Department of Chemistry, University of California, Riverside, California 92521, USA Article (e-mail: [email protected]) About the Author Chris Reed was born a kiwi to English parents in Auckland in 1947. He attended Dilworth School from 1956 to 1964 where his interest in chemistry was un- doubtedly stimulated by being entrusted with a key to the high school chemical stockroom. Nighttime experiments with white phosphorus led to the Headmaster administering six of the best. He obtained his BSc (1967), MSc (1st Class Hons., 1968) and PhD (1971) from The University of Auckland, doing thesis research on iridium organotransition metal chemistry with Professor Warren R. Roper FRS. This was followed by two years of postdoctoral study at Stanford Univer- sity with Professor James P. Collman working on picket fence porphyrin models for haemoglobin. In 1973 he joined the faculty of the University of Southern California, becoming Professor in 1979. After 25 years at USC, he moved to his present position of Distinguished Professor of Chemistry at UC-Riverside to build the Centre for s and p Block Chemistry. His present research interests focus on weakly coordinating anions, weakly coordinated ligands, acids, si- lylium ion chemistry, cationic catalysis and reactive cations across the periodic table. His earlier work included extensive studies in metalloporphyrin chemistry, models for dioxygen-binding copper proteins, spin-spin coupling phenomena including paramagnetic metal to ligand radical coupling, a Magnetochemi- cal alternative to the Spectrochemical Series, fullerene redox chemistry, fullerene-porphyrin supramolecular chemistry and metal-organic framework solids (MOFs). -

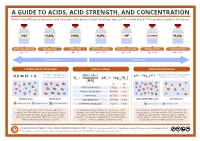

A Guide to Acids, Acid Strength, and Concentration

A GUIDE TO ACIDS, ACID STRENGTH, AND CONCENTRATION What’s the difference between acid strength and concentration? And how does pH fit in with these? This graphic explains the basics. CH COOH HCl H2SO4 HNO3 H3PO4 HF 3 H2CO3 HYDROCHLORIC ACID SULFURIC ACID NITRIC ACID PHOSPHORIC ACID HYDROFLUORIC ACID ETHANOIC ACID CARBONIC ACID pKa = –7 pKa = –2 pKa = –2 pKa = 2.12 pKa = 3.45 pKa = 4.76 pKa = 6.37 STRONGER ACIDS WEAKER ACIDS STRONG ACIDS VS. WEAK ACIDS ACIDS, Ka AND pKa CONCENTRATION AND pH + – The H+ ion is transferred to a + A decrease of one on the pH scale represents + [H+] [A–] pH = –log10[H ] a tenfold increase in H+ concentration. HA H + A water molecule, forming H3O Ka = pKa = –log10[Ka] – [HA] – – + + A + + A– + A + A H + H H H H A H + H H H A Ka pK H – + – H a A H A A – + A– A + H A– H A– VERY STRONG ACID >0.1 <1 A– + H A + + + – H H A H A H H H + A – + – H A– A H A A– –3 FAIRLY STRONG ACID 10 –0.1 1–3 – – + A A + H – – + – H + H A A H A A A H H + A A– + H A– H H WEAK ACID 10–5–10–3 3–5 STRONG ACID WEAK ACID VERY WEAK ACID 10–15–10–5 5–15 CONCENTRATED ACID DILUTE ACID + – H Hydrogen ions A Negative ions H A Acid molecules EXTREMELY WEAK ACID <10–15 >15 H+ Hydrogen ions A– Negative ions Acids react with water when they are added to it, The acid dissociation constant, Ka, is a measure of the Concentration is distinct from strength. -

Acid-Base Theories and Frontier Orbitals

Arrhenius Theory Svante Arrhenius (Swedish) 1880s Acid - a substance that produces H+(aq)in solution Base - a substance that produces OH–(aq) in solution Brønsted-Lowry Theory Johannes Brønsted (Danish) Thomas Lowry (English) 1923 Acid - a substance that donates protons (H+) Base - a substance that accepts protons (H+) Proton Transfer Reaction + + H3O (aq) + NH3(aq) 6 H2O(l) + NH4 (aq) hydronium ion ammonia water ammonium ion + H + H H H H H H O + N O + H N H H H H proton donor proton acceptor = acid = base L In general terms, all acid-base reactions fit the general pattern HA + B º A– + HB+ acid base Conjugate Acid-Base Pairs L When an acid, HA, loses a proton it becomes its conjugate base, A–, a species capable of accepting a proton in the reverse reaction. HA º A– +H+ acid conjugate base L When a base, B, gains a proton, it becomes its conjugate acid, BH+, a species capable of donating a proton in the reverse reaction. B+H+ º HB+ base conjugate acid Acid-Base Reactions L We can analyze Brønsted-Lowry type proton transfer reactions in terms of conjugate acid-base pairs. The generic reaction between HA and B can be viewed as HA º A– +H+ H+ +B º HB+ —————————————————— HA + B º A– +HB+ acid1 base2 base1 acid2 • Species with the same subscripts are conjugate acid-base pairs. Acid Hydrolysis and the Role of Solvent Water L When any Brønsted-Lowry acid HA is placed in water it undergoes + hydrolysis to produce hydronium ion, H3O , and the conjugate base, A–, according to the equilibrium: – + HA + H2O º A +H3O acid1 base2 base1 acid2 • The acid HA transfers a proton to H2O, acting as a base, thereby – + forming the conjugates A and H3O , respectively. -

Catalytic Properties of Zeolites and Synthesized Superacid Systems During the Transformation of Model Reactions of Pentanes

Advances in Engineering Research, volume 177 International Symposium on Engineering and Earth Sciences (ISEES 2018) Catalytic Properties of Zeolites and Synthesized Superacid Systems During the Transformation of Model Reactions of Pentanes Turlov s RA-B. Magomadova Marem .Kh. Heat Engineering and Hydraulics Department of Heat Engineering and Hydraulics Department of Grozny State Oil Technical University Grozny State Oil Technical University g . Grozny, Russia Grozny, Russia e - mail: [email protected] e - mail: [email protected] Madaeva A. D. Idrisova E.U. Heat Engineering and Hydraulics Department Heat Engineering and Hydraulics Department of Grozny State Oil Technical University of Grozny State Oil Technical University Grozny, Russia Grozny, Russia e - mail: ANITA [email protected] e - mail: idrisova999@mail ru Magomadova Madina. Kh. "Chemical technology of oil and gas Department of Grozny State Oil Technical University Grozny, Russia e - mail : [email protected] Abstract—Investigation of the catalytic activity and selectivity II. THE METHODOLOGY OF THE EXPERIMENT of the obtained products of various nature and composition of Before conducting the experiment, the test samples of catalysts in the course of model catalytic reactions, cracking, catalysts (zeolites, AAS and γ-Al2O3) with a fractional isomerization, disproportionation. The study of the acid sites of composition of 0.25 ÷ 40.5 mm were loaded into a quartz these catalysts and their influence on the composition of the reactor, a sample of 0.15 g., the fractional composition of reaction products and the mechanism of conversion of specific C 5 which, as the reactor is filled from the bottom of the reactor to hydrocarbons. The study of the mechanism, speed and direction of the lower part of the catalyst boundary, varies from 2.0 to 0.1 individual stages of multistage reactions implemented scientific mm; then the catalyst and quartz were filled, the fractional and industrial processes. -

Superacid Chemistry

SUPERACID CHEMISTRY SECOND EDITION George A. Olah G. K. Surya Prakash Arpad Molnar Jean Sommer SUPERACID CHEMISTRY SUPERACID CHEMISTRY SECOND EDITION George A. Olah G. K. Surya Prakash Arpad Molnar Jean Sommer Copyright # 2009 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. -

Introduction to Ionic Mechanisms Part I: Fundamentals of Bronsted-Lowry Acid-Base Chemistry

INTRODUCTION TO IONIC MECHANISMS PART I: FUNDAMENTALS OF BRONSTED-LOWRY ACID-BASE CHEMISTRY HYDROGEN ATOMS AND PROTONS IN ORGANIC MOLECULES - A hydrogen atom that has lost its only electron is sometimes referred to as a proton. That is because once the electron is lost, all that remains is the nucleus, which in the case of hydrogen consists of only one proton. The large majority of organic reactions, or transformations, involve breaking old bonds and forming new ones. If a covalent bond is broken heterolytically, the products are ions. In the following example, the bond between carbon and oxygen in the t-butyl alcohol molecule breaks to yield a carbocation and hydroxide ion. H3C CH3 H3C OH H3C + OH CH3 H3C A tertiary Hydroxide carbocation ion The full-headed curved arrow is being used to indicate the movement of an electron pair. In this case, the two electrons that make up the carbon-oxygen bond move towards the oxygen. The bond breaks, leaving the carbon with a positive charge, and the oxygen with a negative charge. In the absence of other factors, it is the difference in electronegativity between the two atoms that drives the direction of electron movement. When pushing arrows, remember that electrons move towards electronegative atoms, or towards areas of electron deficiency (positive, or partial positive charges). The electron pair moves towards the oxygen because it is the more electronegative of the two atoms. If we examine the outcome of heterolytic bond cleavage between oxygen and hydrogen, we see that, once again, oxygen takes the two electrons because it is the more electronegative atom. -

Characterization of the Acidity of Sio2-Zro2 Mixed Oxides

Characterization of the acidity of SiO2-ZrO2 mixed oxides Citation for published version (APA): Bosman, H. J. M. (1995). Characterization of the acidity of SiO2-ZrO2 mixed oxides. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. https://doi.org/10.6100/IR436698 DOI: 10.6100/IR436698 Document status and date: Published: 01/01/1995 Document Version: Publisher’s PDF, also known as Version of Record (includes final page, issue and volume numbers) Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

Chapter Outline

11/16/2016 Aqueous Equilibria: Chemistry of the Water World Chapter Outline • 15.1 Acids and Bases: The BrØnsted–Lowry Model • 15.2 Acid Strength and Molecular Structure • 15.3 pH and the Autoionization of Water • 15.4 Calculations Involving pH, Ka, and Kb • 15.5 Polyprotic Acids • 15.6 pH of Salt Solutions • 15.7 The Common-Ion Effect • 15.8 pH Buffers • 15.9 pH Indicators and Acid–Base Titrations • 15.10 Solubility Equilibria 2 1 11/16/2016 Acids Have a sour taste. Vinegar owes its taste to acetic acid. Citrus fruits contain citric acid. React with certain metals to produce hydrogen gas. React with carbonates and bicarbonates to produce carbon dioxide gas Bases Have a bitter taste. Feel slippery. Many soaps contain bases. Nomenclature Review – Ch 4, Section 4.2 You are only responsible for nomenclature taught in the lab. These ions are part of many different acids and you need to know them! 3- 2- - PO4 , HPO4 , H2PO4 H3PO4 2- - SO4 , HSO4 H2SO4 2- - SO3 , HSO3 H2SO3 2- - CO3 , HCO3 H2CO3 - - HNO HNO NO3 , NO2 3, 2 2- - S , HS H2S - - C2H3O2 (CH3COO ) HC2H3O2 binary acids, oxoacids HCl, HClO4 2 11/16/2016 Strong and Weak Acids A Brønsted acid is a proton donor A Brønsted base is a proton acceptor Strong Acid: Completely ionized - + HNO3(aq) + H2O(ℓ) → NO3 (aq) + H3O (aq) (H+ donor) (H+ acceptor) Weak Acid: Partially ionized - + HNO2(aq) + H2O(ℓ) ⇌ NO2 (aq) + H3O (aq) (H+ donor) (H+ acceptor) 3 11/16/2016 Hydronium Ion Conjugate Acid-Base Pairs 4 11/16/2016 Weak Acids reordered stronger − + CH3COO (aq) [H3O (aq)] Kc = CH3COOH(aq) [H2O(l)] 5 11/16/2016 Strong and Weak Bases Strong and Weak Bases 6 11/16/2016 Weak Bases 7 11/16/2016 Relative Strengths of Acids/Bases Leveling Effect: + • H3O is the strongest H+ donor that can exist in water. -

Proton Affinity Changes Driving Unidirectional Proton Transport In

doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00903-3 J. Mol. Biol. (2003) 332, 1183–1193 Proton Affinity Changes Driving Unidirectional Proton Transport in the Bacteriorhodopsin Photocycle Alexey Onufriev1, Alexander Smondyrev2 and Donald Bashford1* 1Department of Molecular Bacteriorhodopsin is the smallest autonomous light-driven proton pump. Biology, The Scripps Research Proposals as to how it achieves the directionality of its trans-membrane Institute, 10550 North Torrey proton transport fall into two categories: accessibility-switch models in Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037 which proton transfer pathways in different parts of the molecule are USA opened and closed during the photocycle, and affinity-switch models, which focus on changes in proton affinity of groups along the transport 2Schro¨dinger Inc., 120 West chain during the photocycle. Using newly available structural data, and Forty-Fifth Street, 32nd Floor adapting current methods of protein protonation-state prediction to the Tower 45, New York, NY non-equilibrium case, we have calculated the relative free energies of pro- 10036-4041, USA tonation microstates of groups on the transport chain during key confor- mational states of the photocycle. Proton flow is modeled using accessibility limitations that do not change during the photocycle. The results show that changes in affinity (microstate energy) calculable from the structural models are sufficient to drive unidirectional proton trans- port without invoking an accessibility switch. Modeling studies for the N state relative to late M suggest that small structural re-arrangements in the cytoplasmic side may be enough to produce the crucial affinity change of Asp96 during N that allows it to participate in the reprotonation of the Schiff base from the cytoplasmic side. -

Proton Affinity of SO3

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Proton Affinity of SO3 Cynthia Ann Pommerening, Steven M. Bachrach, and Lee S. Sunderlin Department of Chemistry, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, Illinois, USA ϩ Collision-induced dissociation (CID) of the radical cation H2SO4 gives the product pairs ϩ ϩ ϩ ϩ H2O SO3 and HO HSO3 with a 1:3 ratio that is essentially independent of collision energy. Statistical analysis of the two channels indicates that the proton affinity of HO is 3 Ϯ ϭ Ϯ 4 kJ/mol lower than that of SO3. This can be used to derive PA(SO3) 591 4 kJ/mol at 0 K and 596 Ϯ 4 kJ/mol at 298 K. Previously, Munson and Smith bracketed the proton affinity as PA(HBr) ϭ 584 kJ/mol Ͻ PA(SO ) Ͻ PA(CO) ϭ 594 kJ/mol. The threshold of 152 Ϯ 16 ϩ 3 kJ/mol for formation of H O ϩ SO indicates that the barrier to CID is small or nonexistent, 2 3 ϩ in contrast to the substantial barriers to decomposition for H3SO4 and H2SO4. (JAmSoc Mass Spectrom 1999, 10, 856–861) © 1999 American Society for Mass Spectrometry he development of extensive scales of proton this work provide an independent measurement of the ⌬ affinity (PA), gas basicity (GB), and acidity ( Ha) PA of SO3. values has provided a framework for the quanti- The gas-phase addition of H2OtoSO3 to form T ϭϪ⌬ tative understanding of ion properties. (PA H for sulfuric acid has a substantial barrier, as indicated by addition of a proton, GB ϭϪ⌬G for addition of a reaction rate measurements [4–6] and computational ⌬ ϭ⌬ proton, and Ha H for deprotonation.) The history results [7, 8]. -

Acid Dissociation Constant - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1

Acid dissociation constant - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 Help us provide free content to the world by donating today ! Acid dissociation constant From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia An acid dissociation constant (aka acidity constant, acid-ionization constant) is an equilibrium constant for the dissociation of an acid. It is denoted by Ka. For an equilibrium between a generic acid, HA, and − its conjugate base, A , The weak acid acetic acid donates a proton to water in an equilibrium reaction to give the acetate ion and − + HA A + H the hydronium ion. Key: Hydrogen is white, oxygen is red, carbon is gray. Lines are chemical bonds. K is defined, subject to certain conditions, as a where [HA], [A−] and [H+] are equilibrium concentrations of the reactants. The term acid dissociation constant is also used for pKa, which is equal to −log 10 Ka. The term pKb is used in relation to bases, though pKb has faded from modern use due to the easy relationship available between the strength of an acid and the strength of its conjugate base. Though discussions of this topic typically assume water as the solvent, particularly at introductory levels, the Brønsted–Lowry acid-base theory is versatile enough that acidic behavior can now be characterized even in non-aqueous solutions. The value of pK indicates the strength of an acid: the larger the value the weaker the acid. In aqueous a solution, simple acids are partially dissociated to an appreciable extent in in the pH range pK ± 2. The a actual extent of the dissociation can be calculated if the acid concentration and pH are known.